A Father's Day Salute

Staving off the Imperial Japanese Navy in Central Virginia, and other WWII tales

Paid subscriptions help keep Bastiat’s Window going. Free subscriptions are deeply appreciated, too. If you enjoy this piece, please click “share” and pass it along. This piece was adapted from my earlier “A Salute for Lieutenant Graboyes” (2022), published by InsideSources.

Father’s Day is this weekend, and I’ll honor my father, First Lieutenant Harold Graboyes, by recalling a few of his World War II-era Army stories. Among other things, he heard about Pearl Harbor two days before the attack, was ordered to report to Germany as an interpreter despite knowing no foreign languages, was disciplined for criticizing Japanese American internment camps, established strong camaraderie with African American soldiers in a segregated town and Army, and turned down a promotion to captain because it entailed filling out too many forms. I’ll tell his stories, because Dad has been gone for 25 years and can no longer share them himself.

In the peacetime draft preceding World War II, the recruiter asked him which service he would prefer. The Navy, he had heard, had better food, so he requested the Navy. Naturally, then, they put him in the Army and sent him from Philadelphia to Camp Lee, Virginia (later Fort Lee, and now Fort Gregg-Adams), 23 miles south of Richmond.

In early December 1941, Dad had a weekend pass to visit my mother, Lois, in nearby Petersburg. (They married in 1944.) Before he could leave, he was told that all weekend passes were canceled. “Why?” he asked some superior of his. “Because we’re expecting an attack from Japan at any moment” came the answer. The newspapers were filled with ongoing U.S.-Japan peace talks, and Dad was always highly aware of the news. So he asked why the camp’s brass believed war was imminent. One of the camp’s senior officers, it seemed, had a sister who was romantically involved with a Congressman who sat on the Committee on Military Affairs (today’s Armed Services Committee). Hence, the grapevine. As Pearl Harbor was under attack on Sunday morning, Dad said, “I was marching with a rifle, guarding a water tower in southeastern Virginia from the Japanese fleet.” Not prone to conspiracy theories, he always cast a highly skeptical eye toward claims that the bombing of Pearl Harbor was entirely unexpected.

Dad was a loyal soldier, eternally grateful that the service helped lift him from the poverty that befell his family in the lead-up to the Great Depression. He said his one brush with military authorities came when he was reported for openly criticizing the internment of Japanese Americans. He had a close friend in the Japanese American community and thought internment violated basic American principles. Higher-ups told him to keep his thoughts to himself.

At some point, an officer informed Dad that he would soon deploy to Europe as a foreign language interpreter for U.S. intelligence services. That would be a problem, he replied, given that he was not conversant in any foreign language, beyond a few Latin expressions and bits of high school French. The officer, apparently infuriated, accused him of trying to avoid deployment to a war zone.

The misunderstanding arose from Dad’s habit of entertaining friends by pretending to speak a variety of languages—as comedian Sid Caesar did in his routines. (Don’t miss the two Sid Caesar videos in the Lagniappe section below!) Some credulous passerby apparently overhead Dad’s fake foreign language discourses and sent his name up the chain of command as a linguist. For the angry officer, Dad had the difficult task of proving a negative—that he spoke no foreign languages. Apparently, he performed his comedy routine and made his point adequately.

Dad was brilliant, with a deep love of history, physics, and other fields. Poverty and war, though, limited him to a single semester of night classes at the University of Pennsylvania. Fortunately, the Army recognized his brains and made him a highly respected instructor of logistics and military law. His students, he noted proudly, included generals. But he took particular pride in the rapport he enjoyed with classes of African American troops—in a segregated army in a profoundly segregated town.

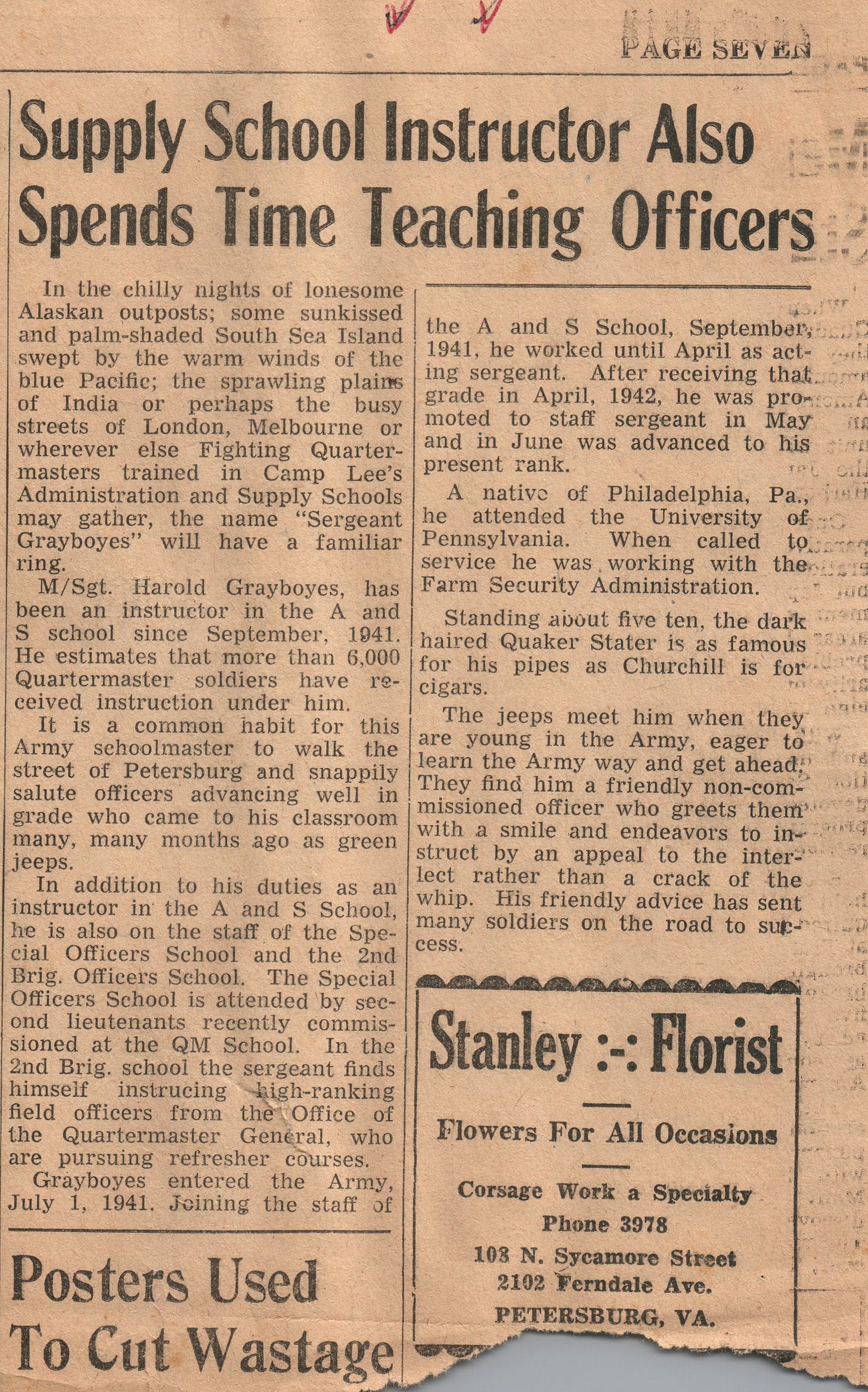

His pedagogical talents led the base commandant to keep him stateside for the duration of the war—and he settled in Petersburg for the remainder of his long life. In his final year of active service, remaining at Camp Lee depended upon his becoming an officer. And so he did—the top graduate and co-regimental commander of his class. (Our home movies show him as an imposing figure, leading the parade at graduation.) After he died, my mother told me—to my complete surprise—that he really had never wanted to become an officer. He loved the life of a master sergeant—the big man on base—whereas second lieutenants were perceived as being a dime a dozen. (The newspaper clipping shown above describes the high esteem in which master sergeants were held.)

Ultimately, he rose to first lieutenant and, in 1953, was offered a promotion to captain in the Reserves after the war. By then, he was married, running a hectic business, raising a son (my brother), and planning to having another child (me). A promotion, he thought, would be nice. But a clerk handed him a phone-book-sized stack of forms to fill in for his promotion. He said he didn’t have time for all that paperwork and took his honorable discharge—always grateful for what the service had given him.

Rest in peace, Lieutenant.

Lagniappe

Here’s comedian Sid Caesar performing the sort of fake-language gibberish that nearly got my monolingual father sent to Germany as an interpreter.

From Nina Porzucki at Public Radio International’s The World radio program in 2014:

Many attribute Caesar’s ear for language to his roots in the multi-ethnic, immigrant neighborhood of New York where he grew up. His parents owned a restaurant where he would hear the different accents of his parents’ patrons. He was also influenced by the radio, says Rabbi Moshe Waldoks, co-editor of the Big Book of Jewish Humor.

“Radio in the 1930s was far more multi-cultural than it is today, so you had characters on the comedy shows who spoke in accents,” Waldoks says.

Caesar was also a musician, and being fluent in music, says Waldoks, was key to Caesar’s ability to pick up the intonations of foreign languages.

“He heard the lilting rhythm of the language,” he adds. “Its tone, and that’s what he was a master at, capturing the tone.”

And here’s Mel Brooks talking about this particular talent of Sid Caesar’s. This includes a skit, written by Brooks, in which Caesar and Howie Morris share this particular talent.

Love this.

In re non-coms vs lieutenants, my dad (also a WW2 vet) was a retired sergeant major. When I was commissioned as a 2LT to start med school, my mother teased him about having to salute me. With a twinkle in his eye he said, "You'll salute me, and I'll salute you. But only *you* will mean it."

And I remember George Gobel on the "Tonight Show" once, talking about spending the war in Oklahoma. When the audience laughed, he said, "Well obviously that's where they needed me, or they wouldn't have sent me there. And I'll remind you that not a single Japanese plane got past Tulsa."

Happy Father's Day!

Thanks for reminding me of Sid Caesar’s genius. I watched him every Saturday night as he, Carl, Reiner, Imogene Coca, and Howard Morris displayed their vast talents, as well as those of their writers, such as Mel Brooks, woody, Allen, and Neil Simon. With this country needs more than anything else just to regain its sense of humor happy Father’s Day.