If you’re not already a subscriber to Bastiat’s Window, please sign up for a free or paid subscription. (Paid really helps!) By all means, share the site and its articles with friends.

The Liberty Fund has kindly granted permission for me to republish my contributions to their October 2022 roundtable on “Systemic Racism in Education and Healthcare.” Our discussion consisted of (1) an introduction by business professor Ramon DeGennaro; (2) essays on healthcare by me and by Darcy Nikol Bryan; (3) essays on education by Harold Black and John Sibley Butler; and (4) summaries of the roundtable by all four essayists. What follows below are lightly edited and rearranged excerpts from my essay (“Tempering Systemic Racism in Healthcare”) and from my summary (“Systemic Racism: Four Intersecting Perspectives”). In an era when the notion of systemic racism both informs and muddles public policy, I highly recommend the thoughts of DeGennaro, Bryan, Black, and Butler, all of whom shed bright light on the topic. The Liberty Fund is “a private educational foundation established to enrich the understanding and appreciation of the complex nature of a society of free and responsible individuals.”

Tempering Systemic Racism in Healthcare

Systemic racism (a.k.a., “institutional racism” or “structural racism”) is the notion that overt racial discrimination in the past (e.g., slavery and Jim Crow laws), has left a residue on the structure of American institutions that yields ongoing inertial patterns of discrimination. For a clear statement of the idea, the Center for Health Care Strategies said, “Racism is embedded in society and we don’t need racists to perpetuate it.” This is a reasonable and legitimate concern—and certainly true in some respects. Unfortunately, many of the policy prescriptions aimed at rectifying these patterns fail to consider the magnitude of their present-day impact, the efficacy of proposed solutions, or the tradeoffs with other societal concerns.

It is productive to identify continuing sources of discrimination, measure the extent of their damage, and seek effective mitigation strategies. Unfortunately, many proponents leap over those steps, assuming on faith that any measured disparities (in health, wealth, employment, etc.) prove systemic racism. They thus dismiss alternative etiologies, such as genetics, personal choices, and measurement errors. They demand policies lacking evidence of efficacy, vilify those who question their conjectures, and advocate breathtakingly authoritarian prescriptions.

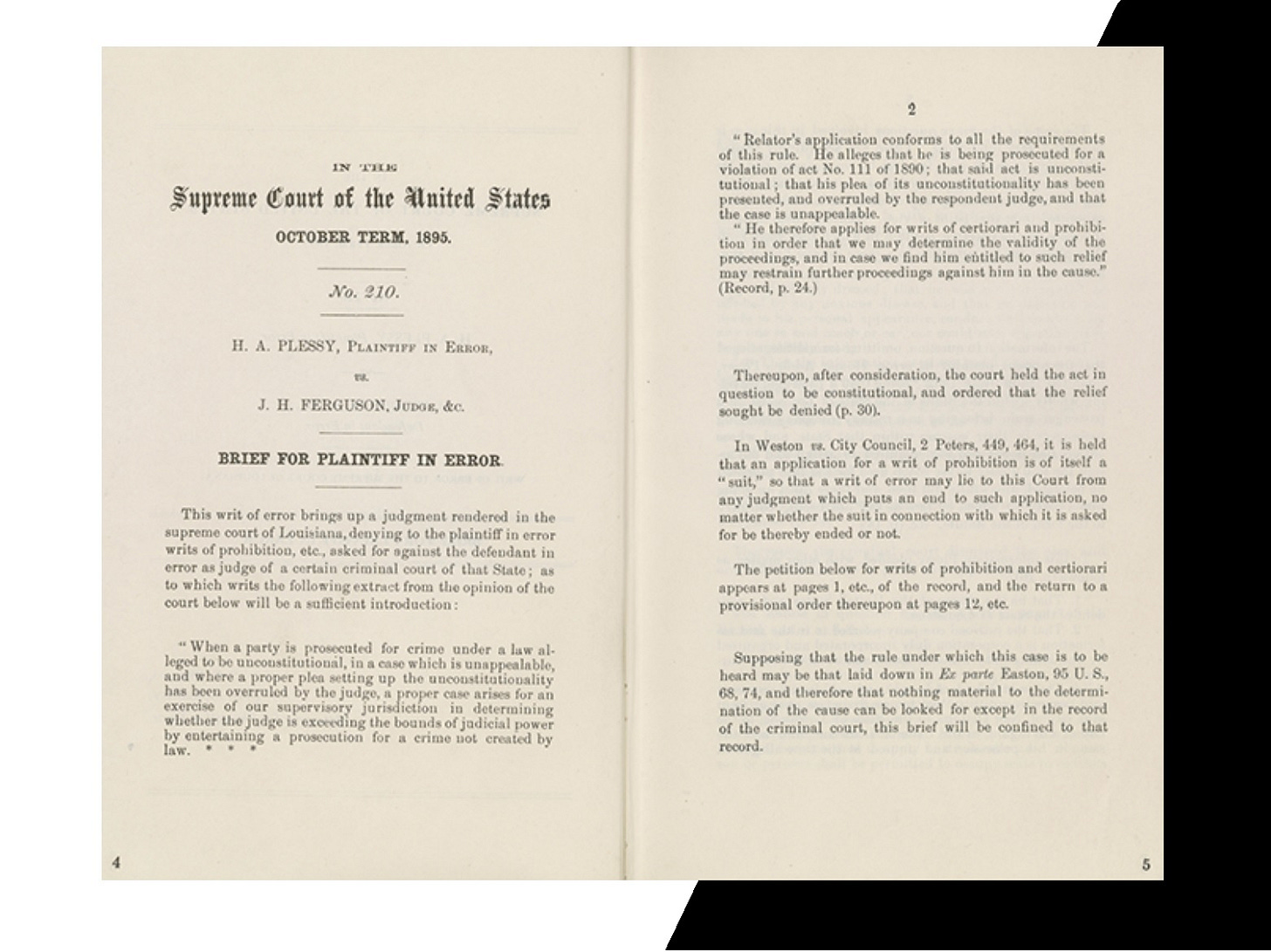

I grew up in small-town, Jim Crow-era Virginia. For my first 15 years, Virginia’s government was monomaniacally focused on “massive resistance” to racial integration and on denying full rights of citizenship to African Americans. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court had okayed the notion of “separate, but equal” in its infamous Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. In response, Virginia adopted a new constitution in 1902, designed specifically to disenfranchise and marginalize African Americans. The state government relentlessly pursued those goals until that constitution was replaced in 1971. It would be surprising if those discriminatory incentives had evaporated entirely, even half a century after purposeful racism dissipated. Conditions in my hometown today suggest to me that the damage done in those years has far from vanished.

Nationally, overt racism was open and endemic up through the 1960s, at which time it did not entirely disappear but was to a considerable degree driven underground. But governmental and social institutions erected pre-1970 in the service of racism lingered on, even if their malevolent intentions had largely dissipated. Today’s housing patterns, dietary habits, access to doctors, and so forth are still influenced by this unfortunate epoch. Some of those patterns continue to have negative impacts on health in minority communities. Healthcare policies and other social policies can and ought to address lingering disparities that still persist from those long-ago abuses.

For example, old-boy networks and family connections still matter in employment and in college admissions. Redlining left terrible wreckage in minority neighborhoods—setting in motion a variety of social pathologies. At the same time, one should not dismiss the reality that well-intentioned policies aimed at ameliorating these wrongs have had perverse effects. Welfare programs’ discouragement of work and marriage is an obvious example.

According to a paper published in its own journal, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) waited 15 years after the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling to “[commit] itself fully to ensuring African Americans, and all minority students, have equal and meaningful access to medical schools.” The result was that “the proportion of African American physicians to African Americans in the U.S. population” was lower in 2010 than it was in 1910.

Structural racism has analogs in classical liberal thinking. Economist Deirdre McCloskey postulates that prior to Western Europe’s “Great Enrichment,” wealth and income had been perpetually depressed by a gauzy anti-entrepreneurial attitude that hung over society, sustained by the rhetoric of various societal institutions. Economist Donald Boudreaux refers to this unwritten phenomenon as a “dishonor tax.” Structural racism could be said to constitute a parallel “nonwhiteness tax”—a plausible economic concept worthy of investigation, measurement, and public policy.

Thomas Sowell and Roland Fryer have investigated and measured the effects of systemic racism. Their analyses stress that (1) The impact of systemic racism on health and other variables is greatly overstated by some in the policy sphere, and (2) The mere existence of disparities does not constitute prima facie evidence of bias. Their work is strikingly exhaustive and persuasive. But purveyors of systemic racism theory are often disinclined to consider such evidence or to debate it dispassionately and honestly. (To be honest, some classical liberals may be too willing to dismiss the idea of systemic racism out-of-hand.)

The mere existence of such effects does not inform us of the magnitude of the problem, the efficacy of ameliorative policies, or the tradeoffs with other social concerns. Ignoring these aspects can and does engender excesses in pursuit of policies. These include:

An assumption that any health disparities between racial groups are primarily, or even exclusively, the result of racism—to the exclusion of genetics, measurement errors, etc.

The encouragement of victimization and discouragement of personal responsibility. Advancing Health Equity, published jointly by the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) said, “People are not vulnerable; they are made vulnerable.” That publication repeatedly suggests that disparities are the result of intentional acts of malevolent parties.

An absolutism and intolerance for debate and investigation. As journalist Bari Weiss notes, “In this revolution, skeptics of any part of this radical ideology are recast as heretics. Those who do not abide by every single aspect of its creed are tarnished as bigots, subjected to boycotts and their work to political litmus tests.”

An inclination toward speech control. The AMA/AAMC document consists largely of 54 pages of mandated speech patterns.

For some advocates, the philosophy underlying systemic racism is not subject to refutation by logic or evidence. Its tautological, Orwellian nature is beautifully crystallized in a statement by psychology professor Angela Bell: “If you have to ask if you are a racist, you are … And if you are not asking if you are a racist, you are.”

A tendency toward a permanent regime of authoritarianism. Antiracism guru Ibram X. Kendi famously wrote: “The only remedy to racist discrimination is antiracist discrimination. The only remedy to past discrimination is present discrimination. The only remedy to present discrimination is future discrimination.”Kendi has proposed a profoundly illiberal “antiracist constitutional amendment.”

Roundtable Essays: Intersecting Perspectives

At its best, systemic race theory is the idea that: (1) Slavery and Jim Crow imbedded overtly racist structures throughout American institutions; (2) Remnants of these structures still incentivize discrimination; and (3) Public policy should strive to reduce such malign incentives. At its worst, systemic race theory is an all-purpose pretext for gutting core principles of American constitutional governance and civil society.

A central question in contemporary America is: How much residual damage remains from overt racism, and what should we do about it? I’ve already summarized my own contributions to the Liberty Fund roundtable, so now, I’ll summarize those of my four colleagues on the project.

In introducing the four essays of this collection, business professor Ramon DeGennaro notes that web searches for “systemic racism in education in the United States” and “racial disparities in healthcare in the United States” return nearly 40 million hits apiece.

Darcy Nikol Bryan is an obstetrician/gynecologist with a long history of serving Medicaid populations. Bryan gently warns against the simplistic poultices that activists would apply to the body politic. She lists sectors where structural inequities remain, adding: “Most, if not all aspects of civic and personal life are captured in this list.” She continues, “I am not sanguine that structural biases are modifiable by expertise and government intervention. … The government cannot ensure healthy behavior in a free society.” “Money,” she notes, “can pile into bureaucratic hands with minimal effect.”

Finance professor Harold Black asks whether systemic racism exists in K-12 education and poses a biting question: How is it that discrimination continues in places where “blacks dominate housing administrators, the education establishment, the police and the justice system?” He asks, “Is the racism of the past so deeply embedded in our schools that the differentials in achievement persist even though many urban school systems have significant numbers of black teachers and black administrators?” He also notes that simple disparity measures between whites and blacks may mask more relevant causal factors (e.g., poverty). Educators, he says, are loading their curricula down with impotent and destructive racial rituals, such as assuming “it is white supremacy to expect a student to write out the mathematical process and show the steps taken to arrive at the answer.”

Sociologist John Sibley Butler offers the most strident, multifaceted criticism of systemic race theory. Systemic racism, he suggests, conflicts with the successes of Jews, Mormons, Japanese Americans, Nigerian Americans, and other sometimes-marginalized groups. Systemic race theory, he says, overlooks social mobility and is especially poor at understanding the African American experience in America. African Americans, he argued, fared better in states with powerful Jim Crow laws than in states with less overt racism. He notes that, to a greater degree, those who remained in Jim Crow states began businesses, built universities, and achieved higher degrees of education. He is unflinching in describing past racism, but also says, “Legal scholars are trying to persecute America, not explain its vast ability to create new opportunities.”

Conclusion

To sum it up, systemic racism is a plausible concept with some degree of veracity. However, policy advocates have a tendency to overstate the actual impacts of this phenomenon, and some have offered startlingly illiberal policy prescriptions as a remedy. The challenge for policymakers is to weigh the evidence, measure the effects, and seek policy prescriptions that are effective and that take into consideration the tradeoffs with other social goals.

Lagniappe

Echoes of History

Just months before the U.S. Supreme Court began its deliberations over Plessy v. Ferguson, Booker T. Washington gave his much-heralded Atlanta Exposition Address. As described on a George Mason University (GMU) website:

“On September 18, 1895, African-American spokesman and leader Booker T. Washington spoke before a predominantly white audience at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. His ‘Atlanta Compromise’ address, as it came to be called, was one of the most important and influential speeches in American history. Although the organizers of the exposition worried that ‘public sentiment was not prepared for such an advanced step,’ they decided that inviting a black speaker would impress Northern visitors with the evidence of racial progress in the South. Washington soothed his listeners’ concerns about ‘uppity’ blacks by claiming that his race would content itself with living ‘by the productions of our hands.’”

Washington’s address is striking in its optimism. He thought the Exposition’s invitation was, “a recognition that will do more to cement the friendship of the two races than any occurrence since the dawn of our freedom.” As links on the GMU page indicates, not all of his contemporaries shared his optimism—or his specific goals. W.E.B. Dubois, for example:

“rejected Washington’s willingness to avoid rocking the racial boat, calling instead for political power, insistence on civil rights, and the higher education of Negro youth.”

At any rate, just seven months later, the Supreme Court would dash any chance of fulfilling Washington’s hopes for a long time to come. The recording is remarkable not only for its tone, but also for its very existence in the earliest days of recording technology. (Note: This recording only covers the opening of Washington’s speech. The entire text is found on the GMU webpage.

To the point about the success of Nigerian Americans, I'll add that Professor John Obgu, Nigerian by birth, was a sociology professor at Berkeley. (Sadly, he died some 20 years ago.) In a remarkable paper on the impact of affirmative action on black students from well-to-do families in the Cleveland area, he found that it greatly reduced their drive to succeed in high school, since they knew that racial preferences would enable them to get into top colleges even without noteworthy achievements. What a contrast from earlier times when black kids were taught that they needed to work especially hard to overcome any bigotry against them. Scholars like Thomas Sowell and Walter Williams grew up in that environment.

> Sociologist John Sibley Butler offers the most strident, multifaceted criticism of systemic race theory. Systemic racism, he suggests, conflicts with the successes of ... Nigerian Americans

I think this is one of the strongest points in the entire article. Recent African immigrants to America by and large don't experience the same societal problems as "traditional" African-Americans (ie. the descendants of slaves) experience. This strongly suggests that something other than race is responsible for the problems. Correlation may not imply causation, but non-correlation absolutely does imply non-causation.

The article mentions Thomas Sowell. His book "Black Rednecks and White Liberals" takes a good look at a more likely cause: the violent and dysfunctional Antebellum South "redneck" culture that the slaves inherited from their masters bears a disturbing resemblance to the worst parts of black American "ghetto" culture today. Southern white rednecks have since moved on with the passage of the better part of two centuries, but with Jim Crow keeping black Americans culturally isolated to a large degree, the descendants of slaves all too often remain stuck with this toxic cultural heritage.