Electoral College as National Firebreaks

National Popular Vote means a 50-state Florida 2000 wildfire every 4 years

CONSTITUTIONAL FIREBREAKS

To those who advocate scrapping the Electoral College and choosing presidents by national popular vote … be very, very careful what you wish for. Among other things, the paragraphs below explain how one highly popular blue-state proposal could force Democratic states to support Republican presidential nominees while leaving Republican states free from such soul-crushing strictures.

Across the American West, fire wardens create firebreaks—vegetation-free swaths gouged through forests and fields to slow and limit the spread of wildfires. In U.S. presidential elections, the Electoral College serves the same purpose—limiting the spread of one state’s malfeasance, manipulation, ineptitude, and/or operational failure to other states. For all the trauma and bitterness that emerged from Florida in 2000, the catastrophe was limited to one state.

For years, a choir of voices has demanded that we eliminate the Electoral College and elect presidents via national popular vote (NPV)—an idea that is appealing in theory, but treacherous in execution. NPV is the electoral equivalent of filling firebreaks with pampas grass, scrub oaks, dead brush, bails of hay, and discarded chemicals. Eliminating the Electoral College could turn virtually every presidential election, every four years, into a 50-state Florida-2000-style conflagration—with a partisan arms race of electoral machinations in the years between elections.

The topic is timely because Democratic vice-presidential candidate Tim Walz declared this month that: “I think all of us know, the Electoral College needs to go. We need a … national popular vote.” The Harris campaign quickly distanced itself from the idea, though Kamala Harris has spoken favorably of the idea in previous years. In 2012, Donald Trump said, similarly, “The [E]lectoral [C]ollege is a disaster for a democracy.” After he won the presidency while losing the national popular vote, Trump reiterated his sentiment, saying, “I'm not going to change my mind just because I won.”

Most likely, NPV would require a constitutional amendment—which won’t happen anytime soon. However, there is an ongoing attempt to circumvent the Constitution via a legally dubious and practically perilous National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (explained below).

FLORIDA 2000, IN FLORIDA, IN 2000

The 2000 presidential election was an apocalyptic event that required the rare confluence of three conditions. First, the Electoral College had to hinge on a single state (or a small number of states). (Flip Florida and you have President Al Gore.) Second, Florida’s popular vote had to be close. (The final difference was 537 votes.) Third, Florida’s electoral process had to be in doubt. (Hanging chads, dimpled chads, butterfly ballots, undervotes, and overvotes raised irresolvable questions about the outcome.) Teams of attorneys swarmed the state. State officials were overruled by state courts which, in turn, were overruled by the U.S. Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore—five weeks after the chaos began.

Al Gore fumed, disappointed supporters continued the drumbeat, and some Democratic bitter-enders still argue that Bush’s victory was illegitimate. Hillary Clinton raised the “selected not elected” accusation at a 2002 fundraiser—14 years before her own defeat under similar circumstances. For years, journalists searched fruitlessly for some recount methodology that would have flipped Florida and thus the national outcome.

Since 2000, questioning the legitimacy of elections and their winners has become a bipartisan civic norm. Flipping Ohio would have made John Kerry president. Senator Barbara Boxer and Rep. Stephanie Tubbs Jones questioned Ohio’s electoral process and briefly delayed the certification of George Bush’s victory. Hillary Clinton attributed her 2016 loss to a conspiracy involving Trump and the Russians. And, of course, Trump and many of his followers have refused to accept the legitimacy of Joe Biden’s election. Preemptive accusations are already being flung in 2024.

FLORIDA 2000, EVERY STATE, ALL THE TIME

With a national popular vote, any close election (like 1948, 1960, 1968, 1976, 2000, 2004, 2016, 2020–and, very likely, 2024) sends parties scurrying for extra votes in every nook and cranny across the nation—with primary emphasis on battleground states. Post-election controversies, however, are limited to those states where the outcome can change the election, where the outcome was close, and where the counting was questionable.

In 2000, there was no point in investigating the voting in California or Texas, since the Gore and Bush victories in those states, respectively, were massive. There was also no need to probe the results in New Hampshire, despite the fact that the results were close and flipping New Hampshire would also have given us President Gore. But, unlike Florida, New Hampshire’s vote-count was pristine; the state had cleaned up its tabulation processes after its disastrous 1974 U.S. Senate race remained unresolved till September 1975.

Now, picture a national election with no Electoral College and a close popular vote nationally. The throngs of attorneys, journalists, and protestors infesting Florida in 2000 would become a 50-state phenomenon. Instead of the U.S. Supreme Court considering the legality of one state’s vote count, the Court would be examining the count in every state.

Without the firebreaks of the Electoral College, the wildfires of Florida 2000 would burn for the full four years before the election. A national popular vote would initiate a nuclear arms race in which states strive to make their electorates redder or bluer long before the first ballots are even cast. With the Electoral College, more Democratic voters in Massachusetts or more Republican voters in Kentucky have no effect on the national outcome. Tilting the voter rolls only matters in the relatively few battleground states. But abolishing the Electoral College hands the officials of every single state a powerful incentive to bolster their own party’s registrations and turnout (by legitimate or nefarious means) and to limit the other party’s numbers. Lower the voting age to 16. Suppress minority registrations. Pad rolls with ineligible or fictitious voters. Strike eligible voters from rolls. Lie, cheat and steal if necessary.

CONSTITUTIONAL WORKAROUND

A constitutional amendment abolishing the Electoral College seems unlikely, but there’s a plan in motion to circumvent the current system—and it’s creeping stealthily toward implementation. Individual states would join together in a National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC), whereby the electors of member states would be expected to vote for the presidential and vice presidential candidates who win the nationwide, not statewide, popular vote. The Electoral College would effectively be abolished when states with 270 electoral votes sign on to the NPVIC. As of today, seventeen states and the District of Columbia, with a combined 209 electoral votes, have signed the NPVIC, with legislation pending in Virginia, North Carolina, Michigan, and Nevada, whose addition would bring the NPVIC signatories to 259 electoral votes—11 short of implementation.

The NPVIC is fraught with constitutional, legal, and practical landmines. You can find an ample inventory in the Wikipedia article or via a Google search. Let me offer two plausible scenarios that I haven’t seen described elsewhere. Both will be based on a hypothetical situation in which VA, NC, MI, and NV sign the compact and are joined by Ohio. This would bring the NPVIC’s signatories up to 276 electoral votes—greater than the 270 required to implement the pact. Let’s imagine that some future race pits J. D. Vance against Tim Walz.

Note: There are lots of other arguments in favor of retaining the Electoral College. Readers may search on their own for those.

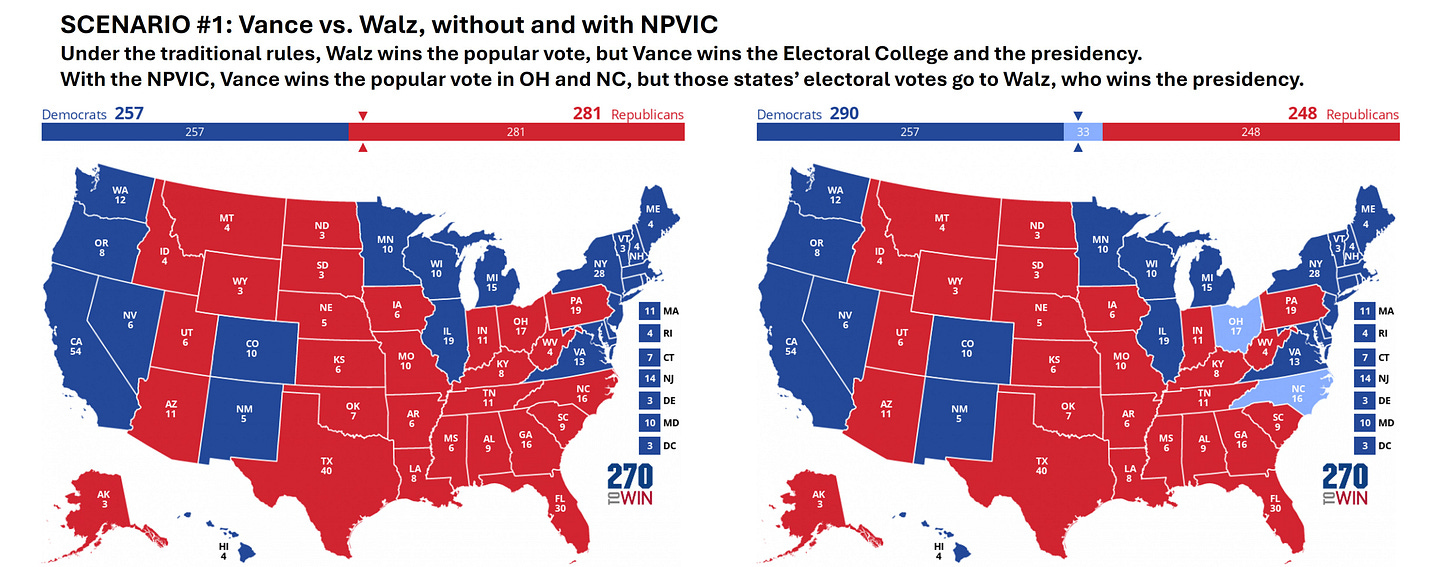

SCENARIO #1: NUCLEAR OCTOBER SURPRISE

Scenario #1 assumes that under the traditional rules, Walz wins the popular vote, but Vance wins the Electoral College and the presidency. But, if VA, NC, MI, NV, and OH have activated the NPVIC, then Walz would be poised to take Ohio and North Carolina, whose voters prefer Vance but whose electors are obliged under the NPVIC to vote for the NPV winner. With the NPVIC in effect, Vance campaigns heavily in California and Massachusetts to boost his popular vote total, and Walz campaigns heavily in Texas and Florida for the same reason.

In early October, however, Republicans in the Ohio legislature see what’s happening and vote to secede from the NPVIC. With signatories down to 259 electoral votes, Republicans in Ohio and North Carolina argue that the NPVIC is no longer in effect, and they award both states’ electors to Vance. Lawsuits, protests, and wall-to-wall news coverage explode coast-to-coast. By comparison, Bush v. Gore seems like a gentle little squabble between bipartisan pals.

Note: An equivalent scenario could easily play out to the detriment of the Republicans with, say, Minnesota withdrawing from the NPVIC to assure a Walz win over Vance.

SCENARIO #2: DEMOCRATIC PARTY RED WAVE

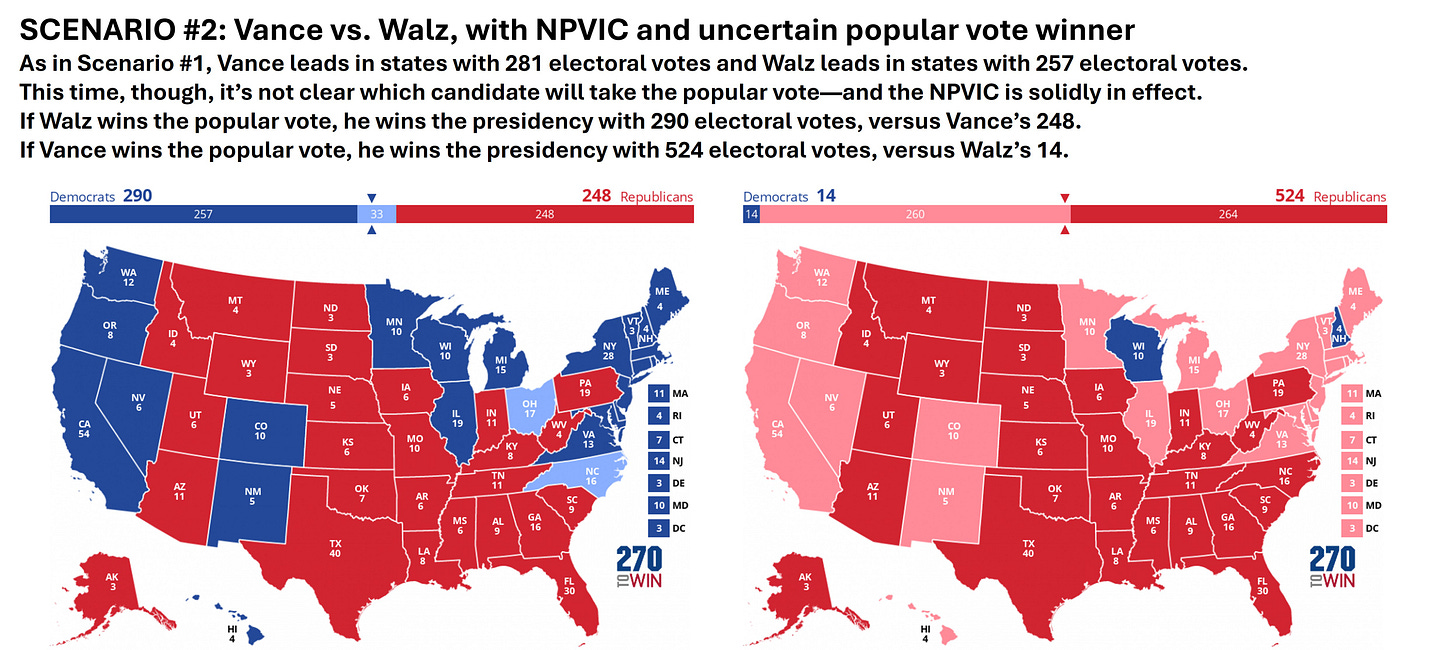

In Scenario #2, as in Scenario #1, Vance leads in states with 281 electoral votes, while Walz leads in states with 257 electoral votes. Two things are different from Scenario #1, however. First, in Scenario #2, no state secedes from the NPVIC, so it remains in effect. Second, it’s not clear before the election whether Vance or Walz will win the popular vote.

The two maps show what happens, depending upon who wins the popular vote. If Walz gets more votes than Vance, he will take the presidency, with 290 electoral votes versus Vance’s 248. Other than Ohio and North Carolina, red states don’t care in the slightest who won the national popular vote—so Vance gets their electoral votes. However, if Vance wins the popular vote, the NPVIC forces most Walz-voting states to cast their electoral votes for Vance. Walz is buried beneath one of history’s greatest Electoral College landslides—receiving only the 14 electoral votes of New Hampshire and Wisconsin—the two blue states that have not signed the NPVIC in this hypothetical. Walz ends up with fewer electoral votes than George McGovern received in 1972 and only one electoral vote more than fellow Minnesotan Walter Mondale got in 1984.

Questions for discussion: In such a circumstance, would the blue states actually honor the NPVIC’s commitment? Could states withdraw from the NPVIC after the November election but before the Electoral College meets? Could blue-state electors go rogue and just ignore their obligations under the NPVIC?

A BRIEF HISTORY OF POPULAR/ELECTORAL VOTE ANOMALIES

The motivation behind the drive for NPV is simple—in 5 out of America’s 59 presidential elections, the candidate who received the most popular votes lost the election to the the candidate who received the second-highest number of votes. Hence, the argument goes, the Electoral College is an affront to “democracy.” Here are some tidbits of that history:

The relevant elections were: John Quincy Adams over Andrew Jackson (1824); Rutherford B. Hayes over Samuel J. Tilden (1876); Benjamin Harrison over Grover Cleveland (1888), George W. Bush over Al Gore (2000), and Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton (2016).

“National popular vote” is a meaningless term with respect to the 1824 election. 11 of the 24 states, with nearly half the country’s population, didn’t record popular votes, so all we know is that Jackson received more votes than Adams in half the country. The election was ultimately decided by the House of Representatives, not by the Electoral College.

With Tilden-Hayes, several states recorded multiple popular vote figures. The outcome was ultimately determined by a special commission. This sort of disaster could occur even with a strict NPV system—and NPV might encourage such situations.

In all five cases, the ultimate loser was a Democrat (though the modern two-party system didn’t exist in 1824).

One can argue that there was one race where the Republican received more popular votes but the Democrat won the Electoral College and the presidency—Richard Nixon versus John Kennedy in 1960. Alabama had a peculiar voting system, where voters chose individual electors rather than casting votes for Nixon, Kennedy, or Virginia Senator Harry F. Byrd (who received a majority of the state’s electoral votes). Given this system, there are multiple ways of calculating the popular vote for particular candidates—none of which is objectively superior. In 1960, the Congressional Quarterly used a methodology that gave Nixon more Alabama votes than any other candidate; if that counting methodology had prevailed, we would say today that Nixon won more votes in Alabama and nationwide than did Kennedy.

In 2000, there was significant pre-election speculation that Bush would win the popular vote while losing the Electoral College—with some Democrats demanding that Republicans promise in advance to accept the Electoral College results.

Had John Kerry done slightly better in Ohio, he would have won the Electoral College while losing the popular vote. Most likely, few Democrats would have called on electors to vote for Bush in the interest of “democracy.”

In 2012, once again, there was much pre-election speculation that the Republican (Mitt Romney) could win the popular vote while the Democrat (Barack Obama) was winning the Electoral College. That year, George Washington University Law School professor Jeffrey Rosen said, “It’s striking that both sides tend to adjust their position on the Electoral College based on whose ox is being gored.”

As for the previous sentence, rather than “based on whose ox is being gored,” perhaps it would be more appropriate to say, “based on whose Gore is being axed.”

ADDENDUM (10/15/24): A few sentences in the above essay also appeared in my 2019 article, “Goodbye Electoral College, Hello Karma,” published by InsideSources.

POPULAR VOTE VERSUS ELECTORAL VOTE, BRITISH EDITION

Lest you think this popular vote-versus-electoral vote conundrum is unique to America, glance at the above graphic and explanation. In 1951, Britain’s Labour Party won the popular vote, while the Conservatives won more seats in Parliament, thus ending the the Labourite Clement Attlee’s tenure as prime minister and returning the Conservative Winston Churchill to #10 Downing Street. Equivalent results have been seen in Canada and in many other nations.

Popular election of the senate drained enough power from the various states. National parties can flood 33 elections every couple of years rather than needing to win thousands of state assembly seats every two year.

Great analysis and explanation. The primary reason I see not to sign up for the national public vote concept is that it removes all traces of influence by the smaller states, essentially making then irrelevant to the process. What do they gain by going along with the herd from CA,TX,FL and NY? Any state legislature that goes along with this is daft.