Free and paid subscriptions to Bastiat’s Window are deeply appreciated. If you enjoy this column today, please subscribe and then share it widely with friends and colleagues.

There’s a move afoot to replace America’s aspirational goal of equality (equal opportunity and equality under the law) with “equity” (equal outcomes designed and implemented by elite experts). A sprawling industry has arisen to spread the gospel of equity across American life. Its catechism has been greatly assisted by an internet-wide burst of colorful little visual parables, all purporting to show the difference between the sins of equality and the blessings of equity. Google “equity,” and your screen will explode with cartoons involving baseball games, apple orchards, blackboards, bike races, street crossings, bookshelves, and more. All of these myriad representations share one identical message.

A web page at the George Washington University’s School of Public Health uses an apple tree metaphor whose lesson seems to be that if you don’t have the sense to move your ladder to the side where the apples are, it’s “inequitable” and someone should install scaffolding and cables to bend the tree toward wherever you stuck your ladder. The website then conjures up a “Magic Benefactor” to explain equality and equity. It’s magic because deserving people are “given” and “allocated” resources, apparently without anyone else required to give up those resources:

“Equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities. Equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.”

As anyone with a knowledge of history and political philosophy knows, a sizable number of countries spent much of the 20th century trying to allocate the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach equal outcomes. The results were far less than equitable. However, as any Swiss banker can tell you, the rulers of these countries did accumulate considerable equity while impoverishing their countries.

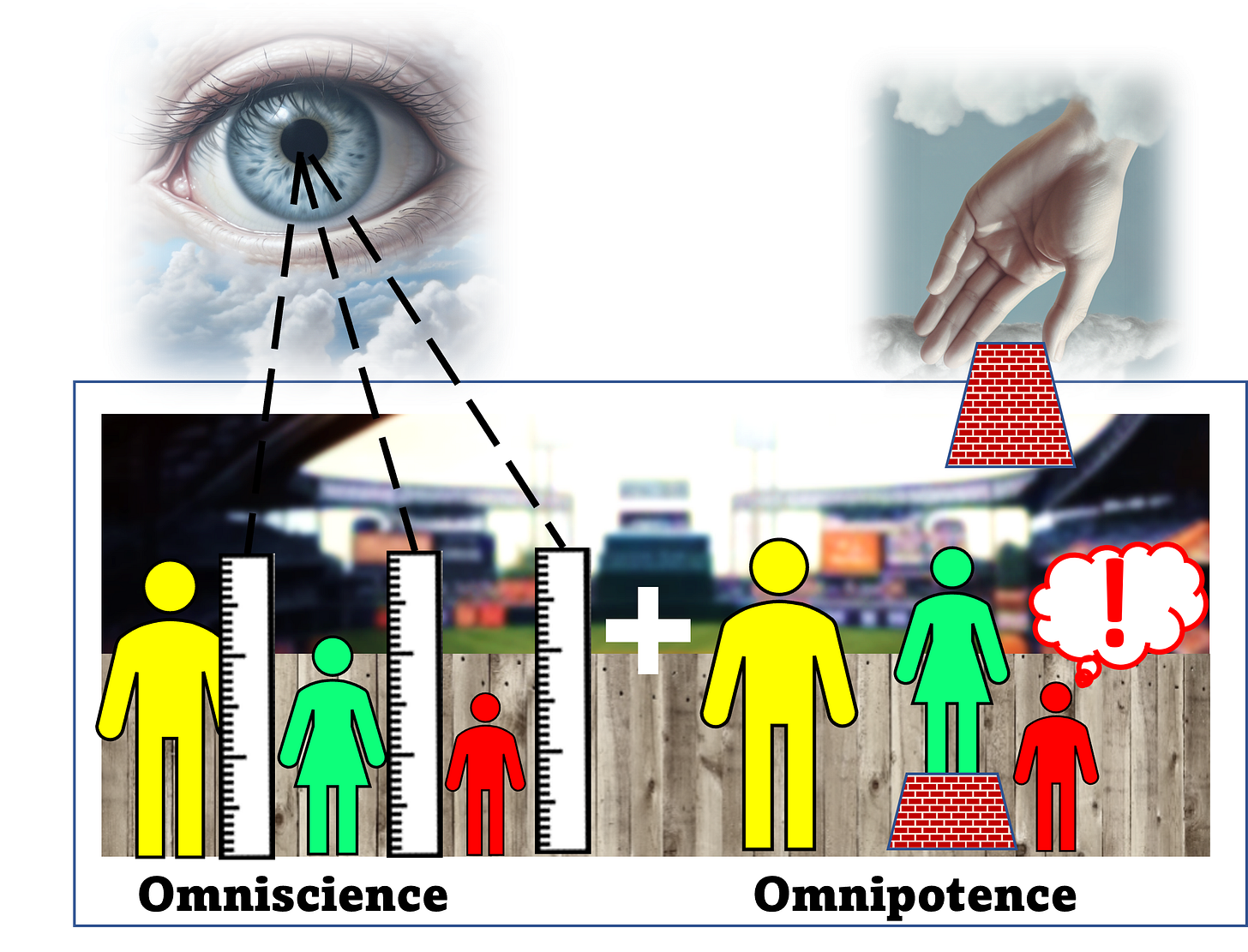

Equity folks have another visual homily, the Stadium & Fence meme, that is brilliantly clever. It’s simple, intuitive, and heartwarming. It is also naïve, misleading, and hubristic. Let’s explore this meme and nine ways in which it fails.

The Basic Stadium & Fence Meme

Three people—Mr. Tall, Ms. Medium, and Mr. Short are all trying to watch a baseball game over a fence. On the left, we see the odious world of equality. Mr. Tall has a clear view. Ms. Medium can barely see the field over the fence. Mr. Short cannot see over the fence at all. On the right, in the putatively just world of equity, some Magic Benefactor has allocated a small pedestal to Ms. Medium and a large pedestal to Mr. Short so all three now have equally clear views of the game. To put it another way, “To each according to his needs.”

Problem #1: “Inequality” is labeled “Equality.”

The left-hand picture doesn’t represent “equality.” An egalitarian would say that the left-hand picture represents inequality—an unfortunate but universal aspect of the human condition. The right-hand picture represents equality—a condition to which an egalitarian aspires, fully cognizant that it will never be fully realized. Bad luck, injustice, one’s starting point in life, and one’s own personal choices inevitably lead to some measure of inequality. Siblings of equal intelligence, from the same household, with identical opportunities often end up in vastly different levels of well-being. The Magic Benefactor can allocate all the resources it wants to Fredo, but he’s never going to be Michael.

Problem #2: The meme assumes an omniscient, omnipotent planner.

With the Magic Benefactor, individuals are helpless, passive beings, devoid of agency. Under equality, an individual is “given” resources and opportunities. Under equity, some unspecified being “allocates” resources and opportunities. In fact, these unnamed allocators are so perceptive and so powerful that they can allocate “the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.” This is no Book of Job or Leibniz theodicy problem—where bad things happen to good people. Rather, it is Candide, where Dr. Pangloss always proclaims this to be the best of all possible worlds.

Problem #3: Redistribution can fail or make things worse.

The past century was littered with redistributive schemes designed to achieve equality of outcomes and which ended in failures. There are monstrous cases, like China’s Cultural Revolution. But also benign cases, like America’s well-intended, but frustratingly ineffective War on Poverty. Central planning (i.e., allocating “the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome”) has a remarkable history of ineffectiveness and counterproductivity—where sincere effort to improve the lot of those at the bottom ensnares them in a poverty trap.

Problem #4: Maybe the tall guy sinks or leaves.

The Stadium & Fence and the Magic Benefactor ignore the fact that with redistribution, the reallocated resources come not like manna from Heaven, but rather from the pockets of living, breathing humans. A more realistic version of this metaphor would show Mr. Tall sinking as Ms. Medium and Mr. Short rise. Or perhaps Mr. Tall just packs up and moves away—leaving no one to pay for the pedestals for Ms. Medium and Mr. Short. This is known in governance as “eroding the tax base” and in folklore as “killing the goose that laid the golden eggs.” In the 1960s, President Lyndon Johnson’s top economic advisor, Arthur Okun, explained this phenomenon beautifully in terms of a leaky bucket.

Problem #5: Maybe those in charge have their own bigotries.

Unlike expert allocators in the Stadium & Fence and the Magic Benefactor, people in charge of real-world redistribution programs are not saintly, unbiased individuals. They come with their own collections of bigotries and deficits of introspection, all reflected in the policies they impose on others. You are disadvantaged only if the elite experts declare that you are disadvantaged. In recent years, for example, Asian-Americans, who suffered terrible discrimination over the course of U.S. history, have been declared by equity “experts” to be “white-adjacent” and, hence, on the losing side of redistribution programs. This reclassification is entirely arbitrary. Coincidentally, the apartheid regime in South Africa implemented a nearly identical redefinition of Japanese, Koreans, and Taiwanese people as “honorary whites”—for entirely cynical reasons.

Problem #6: Maybe the privileged experts in charge just use equity as a pretext to seize more privilege.

One of the more intriguing aspects of the equity agenda is that its proponents effectively say, “Governments, corporations, and educational institutions are hellholes of bigotry and discrimination—so let’s empower governments, corporations, and educational institutions to redistribute resources.” This is popularly known as, “Asking the fox to guard the chicken coop.” It is informative to note the rapidly rising salaries and numbers of equity experts employed by governments, corporations, and educational institutions.

Problem #7: Redistribution focuses on group averages, not individuals.

The Stadium & Fence and Magic Benefactor are both stated in terms of individuals, whereas, in reality, policies are applied to broad demographic groups. In this picture, the Talls are taller on average than the Mediums, who are taller on average than the Shorts. But there wide ranges within each category. Equity policies do not aspire to equalize individuals, but, rather, to equalize group averages. So, for example, when the pedestals are “given/allocated” to the Mediums and Shorts, the shortest member of each group, Talls, Mediums, and Shorts, is still unable to see over the fence, whereas the tallest member of the Shorts—who already had a good view of the game—now has an even better view of the game.

Problem #8: Maybe the problem is the fence, not the people.

The Stadium & Fence meme never bothers to ask how the obstructive fence got there in the first place. A likely explanation is that the fence was erected by the very people with whom equity experts are entrusting with the task of reallocating resources. Access to healthcare, for example, is often impeded by government regulations that limit the number of doctors, that arbitrarily limit the scope of practice of nurse practitioners, that require hospitals to beg for permission to build new neonatal intensive care units—and enrich established insiders. Rather than obsessing over group averages on health, income, education, etc., perhaps the better approach is to rip down the obstacles that self-interested or misinformed bureaucrats and politicians and others have imposed on others.

Problem #9: Maybe the whole fence analogy is deceptive and elitist.

Finally, few, if any, have asked an obvious question that the Stadium & Fence metaphor begs: ”Why are we obsessing over equalizing viewing by three people trying to watch the game from outside the stadium?” There are two possible reasons why these three are where they are, struggling with the fence, rather than enjoying hot dogs in the bleachers with tens of thousands of other people. First, they may be victims of discrimination—excluded somehow from the stadium. If that’s the case, then equity experts are effectively saying, “It’s fine that these three can’t come into the stadium and sit next to us, but let’s make sure these second-class citizens all get the exact same inferior view of the game from the other side of the fence.” Second, perhaps these three are fully capable of buying tickets to the game but choose, instead, to peer over the fence for free. In which, case, why should anyone worry about how well any of them can steal a view of the game?

Don’t have the word-count, but Kurt Vonnegut well described this persistent folly in Harrison Bergeron

You have written such a clear explanation of what’s wrong with the equity idea! I hope this column gets a wide distribution.