For Better Elections, Bring Back Surprises

A Modest Proposal to Improve the Process of Nominating Presidential Candidates

Recently, I offered to contribute 100% of the next $1,000 of my paid subscription revenues to Israel’s EMS personnel and add on an additional 50% from my own pocket. As of today, I’m just a few dollars away from that goal, so as soon as those last dollars come in, I’ll send a $1,500 contribution. Once I have done that, the following new offer will kick in from now till December 1. Thanks to all who opened your wallets to this effort.

Too Late for 2024?

Bastiat’s Window offers no advice on whom the Republican and Democratic Parties should nominate for president or which party voters should opt for next November. Here, I merely lament the process by which those parties choose their nominees. For a half-century, one campaign “reform” after another has sought to reduce the power of rich donors and of party bosses. The result has been to ossify the process, driving away potential candidates, while leaving the plutocrats and pooh-bahs as firmly in control as ever.

For those fretting over prospects for the 2024 election, here’s a story that Minnesota Senator and 1968 Democratic presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy told:

“One thing about a pig, he thinks he’s warm if his nose is warm. I saw a bunch of pigs one time that had frozen together in a rosette, each one’s nose tucked under the rump of the one in front. We have a lot of pigs in politics.”

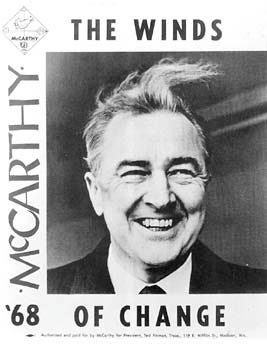

As McCarthy’s quip suggests, he was a loner and oddball, repulsed by Washington gamesmanship and disdainful of fundraising and handshaking. He was also a visionary whose last-minute entry into the 1968 race quickly derailed a president who was badly in need of derailing. That president, Lyndon Johnson, seemed a cinch for renomination and reelection until McCarthy exposed just how weak the president had become. Higher-profile Democrats—notably Robert F. Kennedy—despised LBJ and his Vietnam policies as much as McCarthy but balked at challenging a powerful and vengeful president.

In 2023, as in 1967, broad segments of both parties view their respective frontrunners with trepidation. This week, the Democratic Party is said to be experiencing a “five-alarm fire” over polls showing Joe Biden losing five of six battleground states to Donald Trump. At the same time, many Republicans quake at Trump’s mounting legal problems and his off-putting personality. Both parties have concerns over nominating candidates who are nearing or past the age of 80.

Sirens of both parties wail that it is nearly too late to change the nomination dynamics—that Trump versus Biden is fast becoming inevitable. The reason this is true in 2023 but was not true prior to around 1970 is that do-gooders passed campaign reforms that make it difficult or impossible for anyone to mount a serious presidential campaign unless he or she is willing to spend at least two years meeting with lawyers and accountants, setting up and registering committees, filing papers, and arranging for vast numbers of small contributions—usually gathered by the same power-brokers whom campaign reform was supposed to marginalize. (On that last point, the only exception is that a wealthy candidate like Donald Trump can self-finance.)

So-called reforms have sapped our presidential election system of its once-glorious spontaneity, flexibility, and element of surprise. From the founding of the Republic till the early 1970s, presidential nominations were in flux till the final ballot of the parties’ conventions. Presidential history is rife with avengers—some famous, some obscure—swooping in dramatically to derail unsatisfactory frontrunners. Before 1970, outstanding Americans could wait on the sidelines and seize the podium when parties cried out for better. Below, we’ll look at three years—1880, 1952, and 1968—when the nomination processes took radically unexpected turns in ways that would be nearly impossible today.

To understand why the 2024 race is so maddening for both parties, it is important to see what was once possible, but is now barred by law, regulation, and party rules. Along the way, I’ll even apologize for the itsy-bitsy, teeny-tiny bit of blame that I personally deserve for this sad state of national affairs.

Clean for Gene and Gene Cleans LBJ’s Clock

In 1964, Lyndon Johnson won the largest electoral victory in American history and soon boasted some towering accomplishments. But by 1967, he was a shattered visage, half-sunk in the quicksand of Vietnam. Though not yet 60 years old, LBJ looked like a haggard old man. Many Democrats viewed him as an albatross around their party’s neck and viewed his wartime leadership as abject failure. But still, he seemed a shoo-in for renomination and probably for re-election. For all his failings, he was still a formidable and vindictive force. Challenging him was seen as a suicide mission. The likeliest challenger, Robert F. Kennedy, declined to run and spoke relatively favorably about the prospects for Johnson, whom he loathed. Popular Republican contenders also hesitated to join the fray.

Throughout 1967, antiwar activists talked of Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy taking up the banner, though he was the unlikeliest of presidential candidates. Along with his biting wit, he was obscure, aloof, and condescending. As a young man, he had considered becoming a monk and had become, instead, a small-college economics and education professor. Two decades into his Congressional career, McCarthy was sick of the Senate. His financial position was modest. He did not particularly enjoy campaigning, and he abhorred asking people for money. He did not believe he stood a chance of winning the nomination. But in the unreformed campaign environment of 1967-68, McCarthy could run a quixotic campaign to press Johnson on Vietnam.

In late 1967, a group of wealthy donors simply went to McCarthy and said, effectively, “Here’s all the money you need. You just go out and talk about LBJ and Vietnam.” A rag-tag army of volunteers shaved their beards, cut their hair, and dressed conservatively in the name of “Clean for Gene.” Thus relieved of the hateful aspects of campaigning, McCarthy entered the race on November 30 and nearly defeated Johnson in New Hampshire on March 12. Seeing Johnson wounded, Kennedy entered the race on March 16. Johnson announced his retirement on March 31, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey entered the race on April 27. Kennedy was assassinated on June 5, and South Dakota Senator George McGovern, a close Kennedy ally, entered the race on August 10. On August 28, Humphrey won the nomination.

The Republican race was almost as chaotic. Governor George Romney became the first major candidate on November 18. In mid-January, Ronald Reagan said he would seek California’s delegates as a bargaining chip, but wouldn’t campaign elsewhere. Richard Nixon entered on February 1. After a fatal gaffe, Romney withdrew on February 28. Nelson Rockefeller toyed with running and finally announced his candidacy on April 30. On August 5, Reagan announced that he would, in fact, be a candidate. On August 8, Nixon won the nomination.

Very likely, without McCarthy’s late and mercurial entry into the race, Johnson’s weakness would never have been verified, Kennedy would never have entered, and Johnson and Humphrey would have been renominated and reelected. And under today’s rules, no one like McCarthy would ever imagine running.

I Like Ike and Madly for Adlai

1952 also saw nominating processes would never be possible under today’s campaign rules. As New Year’s Day approached, it seemed likely that Democrats would nominate Harry S Truman for a second full term and that Republicans would nominate Ohio Senator Robert A. Taft. However, like LBJ 16 years later, Truman was managing an unpopular war and plunging in the polls, and Taft was something of a dreary isolationist. As in 2023, many in both parties hoped for someone different, but it wasn’t obvious whom either party could substitute.

Sensing Truman’s weakness, on December 16, 1951, Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver announced his candidacy. A February 15 poll showed Truman in deep trouble, and Kefauver defeated him in the New Hampshire primary on March 11. Truman withdrew from the race on March 29, leaving Kefauver as the frontrunner. Truman and other party leaders, however, disliked and distrusted Kefauver. They considered perhaps 10 other possible candidates but settled on Illinois Governor Adlai E. Stevenson. Stevenson declined to run, preferring to seek re-election as governor—though he didn’t entirely shut the door on running. When the Democratic National Convention convened on July 21, Stevenson still declined to run, though party leaders persuaded him to change his mind. On July 25, Stevenson was nominated.

In 1952, Republicans faced a choice that pitted the tepid versus the weird. The frontrunner was Robert A. Taft, the bland and isolationist son of former President William Howard Taft. There was also talk of General Douglas MacArthur—perceived to be something of a narcissistic loon. California Governor Earl Warren didn’t catch fire, and neither did former Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen, who was in the process of transitioning from fading star to perennial joke.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, then serving as president of Columbia University and as Supreme Commander of NATO, was an object of speculation—in both parties. In 1948, Truman had tried persuading Eisenhower to run on the Democratic side—with Truman dropping back to the vice presidency—but Ike decided he was a Republican. In 1952, Republicans, dissatisfied with their choices, pushed an Eisenhower candidacy. As an active member of the U.S. military, he could play little role in these machinations. However, on May 31, 1952, he retired from the active military service and announced his candidacy four days later. One month later, the Republican National Convention nominated Eisenhower for president, and he was elected four months later. He tendered his resignation from Columbia’s presidency in mid-November and stepped down from that office the day before his presidential inauguration.

As in 1968, the nomination process in both parties was tumultuous and loaded with uncertainty until the parties convened. While one can criticize Eisenhower, Stevenson, Humphrey, and Nixon, it is likely in each of these four cases, the conventions selected the strongest possibilities. Whatever their eventual shortcomings, all four were brilliant leaders.

We Want Garfield

In 1880, the Republican race for the presidency came down to a depressing choice among three dreary candidates. Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency had been less than stellar, and in 1880, he was well past his prime. James G. Blaine was a slippery character who, four years later, would win the Republican nomination and famously blow the general election. John Sherman was a lackluster former Ohio senator.

Ohio Congressman James A. Garfield had serious doubts about his political ally, Sherman, but dutifully agreed to give his nominating speech at the Republican National Convention. Garfield was one of the most gifted orators of his time—brilliant and immensely likeable. As described by Candice Millard in her Destiny of the Republic, Garfield stood before the Convention to nominate Sherman and, in a dramatic flourish, asked his audience:

“‘And now, gentlemen of the Convention,’ he said, ‘what do we want?” From the midst of the crowd came an unexpected and, for Garfield, unwelcome answer. ‘We want Garfield!’”

And thus began the tide that swept the mediocrities away and landed Garfield in the White House. Millard’s book and subsequent reading have persuaded me that Garfield may well have been the most outstanding individual ever elected president—one who, but for an assassin’s bullets, might have averted the racial and sectional divisions that have riven the nation for the succeeding 142 years.

Biden and Trump, Trump and Biden

And so, here we are in November 2023, as some voices in both parties are increasingly frantic in warning that it will soon be too late to challenge the current president and his immediate predecessor for their respective nominations. Furthermore, if either Joe Biden or Donald Trump were to depart from the campaign, next Spring or Summer, the nomination process in that party would be thrown into turmoil. Keep in mind that the window for 2024 is said to be shutting around the time that it was just beginning to open in 1880, 1952, or 1968.

Each party today has its list of oft-mentioned but too-late-to-enter possibilities—Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and California Governor Gavin Newsom come to mind. And, no doubt, both parties have their Garfields and Stevensons—dark horses of capturing their parties’ nominations at some precise moment between now and the conventions. But with the labyrinthine requirements that contemporary laws impose on candidacies, it would be difficult to impossible for a Garfield or Eisenhower or Stevenson to emerge from the stasis at such late dates.

Today’s candidates have to set up their own sprawling campaign bureaucracies, file endless documents, raise funds in small amounts, and so forth. The problem was satirized on TV’s police sitcom Barney Miller in 1980. In that episode, officers haul in one Alfred Royce, a lunatic who claims to be running for president. Royce is arrested for holding up a grocery store full of shoppers at gunpoint, demanding that they give him small “voluntary” contributions so he could qualify under federal law for matching contributions. (He offered that among his first priorities as president would be gun control.)

So, how do we restore the flexibility that we legislated away? My modest proposal—and it’s just a random thought for your consideration—is to repeal every bloody word of federal election law enacted since 1970 and dismantle the bureaucracies erected to implement those laws.

Mea Culpa

I will admit just a sliver of culpability for all this mess and apologize for my role. At age 18, I was elected as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, and there I voted for George McGovern’s nomination. Campaign reform was high on the agenda of that convention and one of the convention votes for that reform was mine. (Actually, I had only half a vote—the result of a legal battle with a competing delegation.)

Looking back on what those reforms have done to American elections, I ask myself why I supported them—and my answer comes from the classic Western, The Magnificent Seven. In that film, Vin (Steve McQueen) was a gunslinger hired to defend an impoverished village in Mexico. After a battle, he was captured by the bandit chieftain Calvera (Eli Wallach), who asked why he accepted such a hopeless assignment. Vin answered, “It’s like a fellow I once knew in El Paso. One day, he just took all his clothes off and jumped in a mess of cactus. I asked him that same question, ‘Why?’” Stunned, Calvera asked why the man had done so. Vin responded, “He said, ‘It seemed to be a good idea at the time.’”

LAGNIAPPE

It’s hard to imagine a better example of the stereotypical innocence of the 1950s than this Eisenhower campaign ad.

Many reforms are reactions against evident problems. Today's two-year Presidential primary campaigns are a popular reaction against the past practice of party insiders choosing nominees. The weaknesses of the two-year primary campaign are evident, such as the exorbitant cost of primary campaigns. It puts a premium on name-recognition. Voters in the later primaries get to choose among candidates who won the earlier primaries so every state competes to conduct early primaries. But, would we be better off if our Presidential nominees were selected by a handful of party insiders in now smoke-free rooms at party conventions?

Do “better elections” produce more liberty?