Goat Glands versus Polio Vaccine

Finding the Sweet Spot in Occupational Regulation. [Plus, the most famous all-girl band that no one's ever heard of.]

This is a shortened and lightly-edited version of an article just published by the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at West Virginia University, where I am a Senior Research Affiliate. You can read the full version online as a blogpost or download it as a PDF.

Paid subscriptions help keep Bastiat’s Window going. Free subscriptions are deeply appreciated, too. If you enjoy this piece, please click “share” and pass it along. Persuade two friends to subscribe, and you will make my day.

How do you craft occupational regulations that allow Jonas Salk to test his polio vaccine but prohibit John Romulus Brinkley from implanting goat testicles into gullible members of his radio audience? This, in brief, is the fundamental question that one faces in crafting occupational regulations for medical professionals.

Occupational regulations are supposed to protect the public from unscrupulous or incompetent practitioners, but almost any regulations devised will exhibit one or both of the following: (1) allowing some harmful practices to proceed apace, and (2) prohibiting some beneficial practices. The only way to eradicate the first failing is to prohibit everything. The only way to eradicate the second failing is to prohibit nothing. Therefore, crafting regulations requires policymakers to consider the tradeoffs between these two failings and to plant their flag at some sweet spot that is, at least in part, subjectively determined.

For example, requiring practitioners to meet standardized education requirements in board- or state-approved schools ensures with a high degree of certainty that all practitioners will share a certain set of mandated competencies. But such standardization discourages risk-taking and heterodox thinking. This can limit the types of care available and stanch the development of technological innovations.

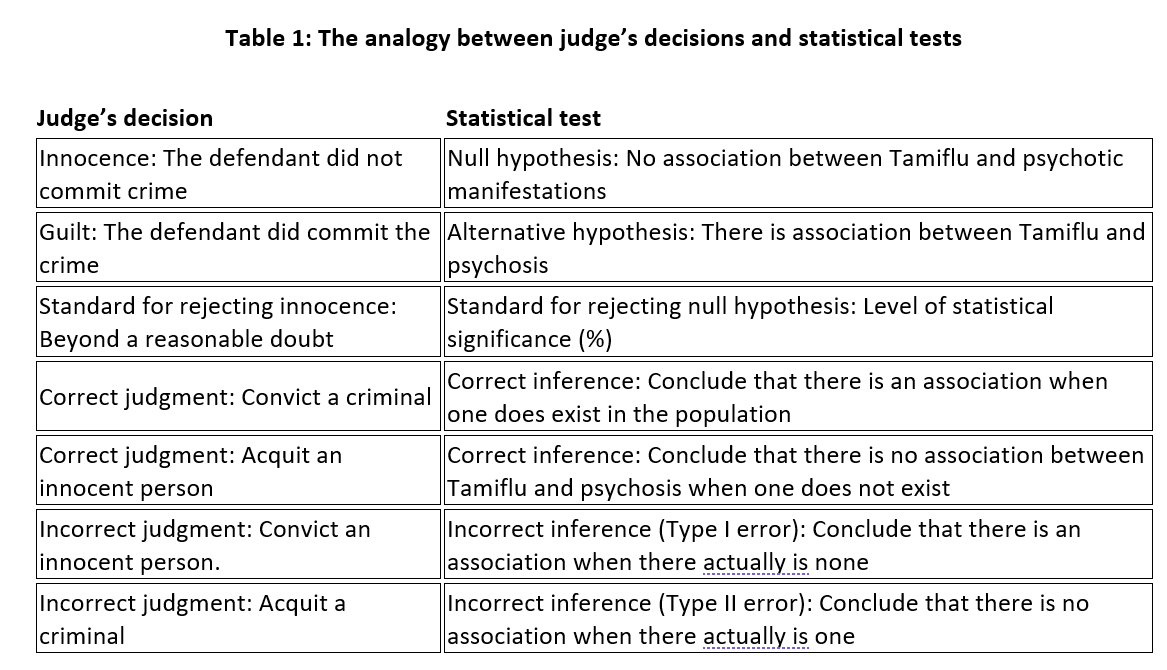

In science, the equivalent tradeoff problem is known as the “Type I/Type II error” problem. In hypothesis testing, a Type I error is a false positive, and a Type II error is a false negative. A webpage at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) portrays hypothesis testing as analogous to a judge’s decision in a criminal trial.

Judges and Scientists, Verdicts and Proofs

In American jurisprudence, convicting an innocent person is considered a far worse travesty than acquitting a guilty person. Hence, the default assumption is that the defendant is “innocent until proven guilty” and should not be found guilty unless the evidence suggests guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” In the hypothesis testing example shown in the table, the researcher is asking whether the vaccine [antiviral drug] Tamiflu is guilty of provoking psychotic manifestations. The default assumption (“null hypothesis”) is that the Tamiflu vaccine should be considered innocent until proven guilty, beyond a reasonable doubt. In the case of drug testing, “beyond a reasonable doubt” means that there is a very low probability (say, 5 percent or 1 percent) that the data would suggest an association between Tamiflu and psychosis if no such association exists in reality. The fact that “Tamiflu is innocent” is the null hypothesis might suggest that the researchers think that wrongly tarnishing the drug’s reputation poses a greater danger than missing an actual Tamiflu/psychosis association.

We can borrow the NIH’s schema and view occupational licensure as equivalent to a judge’s decision in a criminal trial. More narrowly, we could apply this reasoning to scope of practice, which is, in effect, a license to perform a specific task. In Tables 2 and 3, we’ll explore how these fit the Type I/Type II schema.

How one formulates the null hypothesis is in part subjective, reflecting complex philosophical angles. American jurisprudence favors “innocent until proven guilty,” whereas some countries effectively mandate “guilty until proven innocent.” The NIH table implies that incorrectly associating Tamiflu with psychosis is worse than correctly failing to correctly associate Tamiflu with psychosis. One could also formulate an hypothesis in the opposite manner.

Judges and Licensers, Verdicts and Licenses

We can apply the same equivalence to judges and those charged with granting and denying healthcare licenses. Table 2 implies that barring a scrupulous, competent practitioner from practicing healthcare is worse than allowing an unscrupulous incompetent to slip through at times. Table 3, on the other hand, assumes that allowing an unworthy practitioner to treat patients is worse than barring a worthy practitioner. It’s sort of a glass-half-full/glass-half-empty choice.

In Table 2, perhaps the licensure hurdles are set high enough to allow 10 unworthy practitioners to slip through in order to allow 1 worthy practitioner to operate. Or, maybe we’re more risk-averse and tighten the regulations to make the ratio 5-to-1. Doing so will likely mean fewer unworthy practitioners, but also fewer worthy ones.

Table 3 implies the opposite mode of thinking. Perhaps we’re willing to bar 10 worthy practitioners from treating patients if doing so prohibits a single unworthy one from doing so. Or, perhaps we loosen the regulations to make the ratio 5-to-1.

[OMITTED MATERIAL: Here, the complete text of this article on the Knee Center website addresses a series of questions related to regulation of healthcare professionals, including: Is the Food and Drug Administration too cautious or too aggressive? How should medical artificial intelligence be regulated? Has medical licensure done more good than harm? Are occupational regulations designed to protect inside providers, or to protect patients from undue risks?]

Brinkley and his Kids (Goats)

John Romulus Brinkley was a controversial Kansas doctor (later Texas) who pioneered the useless and dangerous practice of implanting goat testicles in men who believed they were impotent or sterile. (Brinkley called them “goat glands.”) He had more or less purchased a medical degree from a shoddy diploma mill. He attracted his voluminous clientele by, for all practical purposes, inventing talk radio. He would give folksy, dire medical sermons about the supposed prevalence of male reproductive problems and promote his bizarre surgical procedure as a cure-all.

To attract a larger audience, he constructed what was likely the most powerful radio station in American history, with a range stretching from Canada to Mexico—powerful enough to be audible on bedsprings, barbed-wire fences, and dental hardware. His sermons were interspersed between offerings of cutting-edge country-and-western music—helping to launch the careers of Red Foley, Patsy Montana, Jimmie Rodgers, Gene Autry, the Carter Family, and a host of others.

Some recipients of his implant patients became sick and disabled. Others died. Brinkley issued 42 death certificates for patients who, it is said, were not ill when they came to his clinic.

[OMITTED HERE: The complete text of this article on the Knee Center website has additional material on Brinkley’s bizarre history, including his near-successful run for governor of Kansas (staged to regain his revoked medical license) and his later dabblings with Nazism.]

Salk and His Kids (Human)

Jonas was also a colorful and controversial doctor, though the nature of his controversies were far more elevated than those surrounding Brinkley. After the release of his polio vaccine, Salk was evermore a celebrity in the public eye. While Brinkley had his country music artists, Salk eventually married Françoise Gilot, an accomplished ceramics and watercolor artist who had been Pablo Picasso’s lover.

Like Brinkley, Salk pioneered an utterly unconventional medical treatment, to the consternation of many in the medical establishment. He pushed the boundaries of medical practice to apply his treatment to millions of patients (as opposed to Brinkley’s thousands). As with Brinkley, there were deaths along the way. But unlike Brinkley, Salk developed a pathbreaking preventative that helped end a nationwide scourge of death, compared with Brinkley’s useless, dangerous treatments. And, unlike Brinkley, there were no questions about Salk’s credentials or institutional base. Nevertheless, historian David Oshinsky, a leading chronicler of Salk’s work, concludes that the sort of work that Salk did would likely be impossible today, due to increased government restrictions and increased parental risk-aversion.

Before Salk’s vaccine, the American populace was gripped by terror of waves of the disease sweeping across the population. For a visual look into the disease, one can watch this brief video of Paul Alexander, who fell victim to polio in 1952 at the age of 6. As of this writing (6/12/23), Alexander has spent 71 years in an iron lung with constant care. Through efforts unimaginable to most of us, he was able to attend K-12 schools, go to college and law school, and practice as a trial lawyer. As of today, he is the last polio victim who remains in an iron lung—the maintenance of which has become a challenge, as parts and experienced mechanics have disappeared from the scene.

[OMITTED HERE: The complete text of this article article has additional material on Salk’s history, including statistics on the waves of polio epidemics, Salk’s status as an outsider in the medical profession, and assertions that research like his would never be allowed today.]

As a personal aside, I can never mention Salk without noting a cherished memory shared by my wife, Alanna Graboyes. She grew up in the Atlantic beach community of Far Rockaway, New York. In 1955, her parents escorted her to a block party held in honor of their summer neighbor, Jonas Salk, to celebrate his success in producing his vaccine. She recalls him sitting like royalty in a large wicker chair where neighbors would receive a handshake or, in her case, a hug from the good doctor.

Lagniappe

Recommended Reading/Listening: “O Sister, Where Art Thou?”

Once in a while, a story comes along that just blows me away. The essays I write often involve music, history, politics, public policy, Americana, eugenics, famous people who come out of nowhere, famous people who disappear into nowhere, crime, charitable souls, and wounded hearts. This week, I stumbled across an article that had all of these—a 20-year-old Texas Monthly piece called, “O Sister, Where Art Thou?” written by Skip Hollandsworth. I subsequently found a 2-year old, 15-minute podcast in which Hollandsworth retells the story.

The article begins with a broad summary:

In the early forties, eight inmates of the Goree prison unit [in Huntsville, Texas] formed one of the first all-female country and western acts in the country, capturing the hearts of millions of radio listeners. Then they nearly all vanished forever.

I’ll share just the barest details and let you enjoy the rest in Hollandsworth’s fine writing and speaking. The inmates were women, all in their teens and twenties. They had been convicted of theft, robbery, cattle rustling, murder, and more. Most had no experience with singing or playing instruments. The Goree prison unit was a place of hard labor, rigid rules, and painful punishments for violators. The warden’s wife was a compassionate soul who worked to prepare inmates for the day they would re-enter society. Through an unbelievable sequence of circumstances, these eight women came together as the Goree All Girl String Band and were invited to appear on a country-and-western radio program,Thirty Minutes Behind the Walls, that featured performances by prisoners. For several years, they were a nationwide sensation with millions of fans—arguably one of country’s first female supergroups. Then, one by one, they were paroled and vanished. Once freed, the women, who were deeply embarrassed by their prison records, went to extraordinary lengths to hide their pasts. So far as anyone knows, not a single recording exists of their performances, though crisp, beautiful photographs remain of the women, dressed in cowboy-music finery, smiling, decked out with guitars, mandolins, fiddles, and bass fiddles—destined only for obscurity and a few internet stories long after.

One reason for the band’s existence was their hope that respectable fame might persuade Texas Governor Wilbert Lee, “Pappy” O’Daniel to grant them early release from prison. (A fictionalized version of O’Daniel appears as the patron of the prison escapees’ band in the Coen Brothers’ film, O Brother, Where Art Thou?) As Hollandsworth wrote of the Goree Girls, “They may have been the only band in musical history that set out to gain attention in order to disappear.”

Robert F. Graboyes is president of RFG Counterpoint, LLC in Alexandria, Virginia. An economist, journalist, and musician, he holds five degrees, including a PhD in economics from Columbia University. An award-winning professor, in 2014, he received the Reason Foundation’s Bastiat Prize for Journalism. He publishes Bastiat’s Window, a Substack-based journal of economics, science, and culture. His music compositions are at YouTube.com/@RFGraboyes/videos

Wonderfully informed and precise writing - thank you!

Really enjoyed the radio broadcast.

Lola