If You’re Breathing, There’s Still Time.

A tale of lives restarted and restarted again, and then restarted once again

Over the years, many of my students and younger colleagues have come to me with sad faces to say, “I’m not happy with my job or my career prospects. But I’m too old to make a big change. Life has passed me by. I’m stuck. It’s too late.” At that point, wishing to pry them from their despair, I tell them a story about a friend’s father—told to me decades earlier by my friend (or perhaps by his wife). Recently, I asked that friend for permission to tell his father’s story at BASTIAT’S WINDOW, and he kindly allowed me to do so. He corrected some errors in my storytelling and offered some additional information I had never known. (I’ve lifted a little of the text here from his words.) In particular, he noted that his mother’s story is as impressive as his father’s and provided information on her journey. With gratitude to my friend and his wife, here is a tale about what is possible later in life—even when you or those around you are convinced that it is time to give up.

RESTARTING

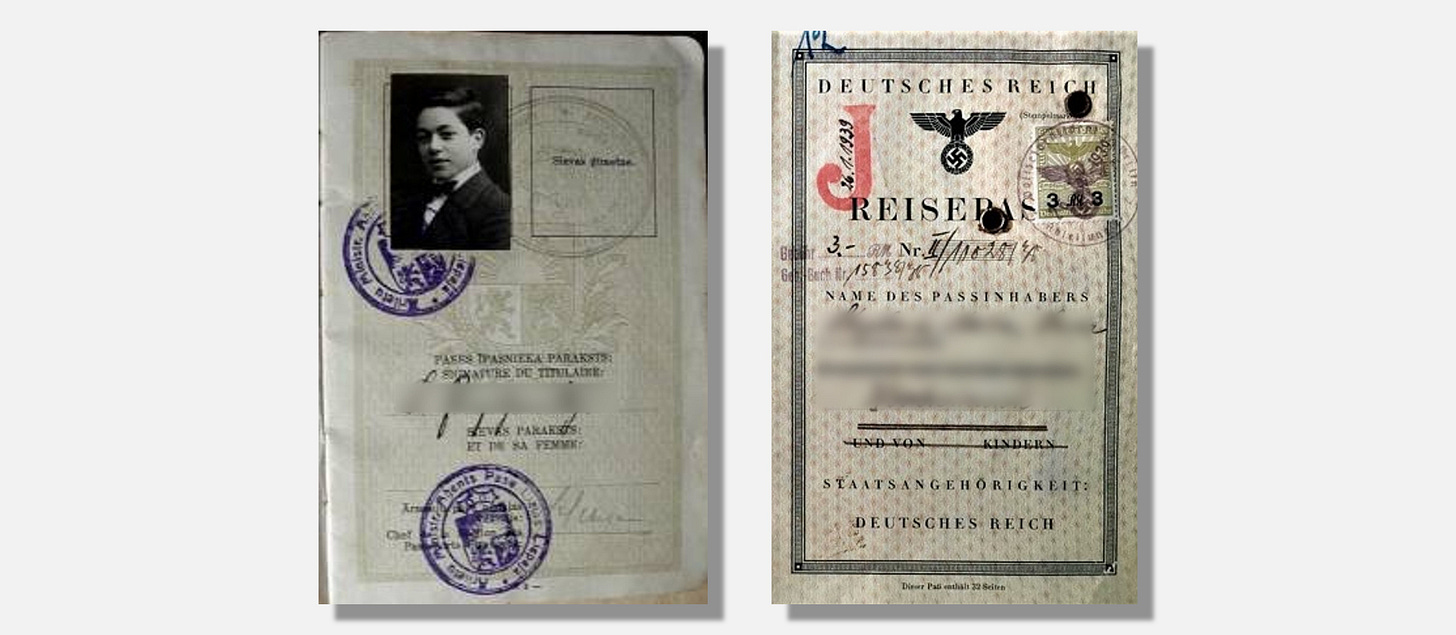

My friend’s father was from Latvia (then part of the Russian Empire), and my friend’s mother was from Germany. Let’s call them Mr. and Mrs. P**. Both were Jewish. Each left Europe to escape deteriorating political situations on that benighted continent. Both settled in Uruguay, where they met and married.

To understand the dire circumstances they left behind, look at Mrs. P**’s passport in the montage above. The swastika and gigantic letter “J” stamped in red tell you all you need to know. Mr. P**, whose passport also appears above, came to Uruguay in 1925, age 18, with one cousin. A year later, he brought his parents and all but one sibling over. His married sister, who stayed behind in Latvia, would later be murdered by the Nazis. Mrs. P** came from a wealthy family that managed to leave Germany in 1939 on the last ship out of Hamburg.

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE, EXHIBIT “A”

Mr. P** had always wanted to be a doctor, but that was an unattainable dream when he arrived in Uruguay. A stranger in a strange land, he had to learn Spanish and earn a living. He held a variety of blue-collar jobs and eventually became a professional window installer and repairman. As soon as he could afford to do so, he started taking evening classes at the university, subsequently enrolling in medical school as a part-time student.

It would take Mr. P** 20 years from his arrival in Uruguay to complete the requirements for his medical degree. At age 38, already a husband and father, Mr. P** finally fulfilled his dream and became Dr. P**. He worked as a family physician, but also conducted research on diseases transmitted by animals (rabies, in particular) and on the medical properties of algae. He became a top figure in Uruguay’s efforts to combat rabies and served as an advisor on the subject to the World Health Organization. This work would carry him from age 38 till his mid-60s. Then, life became turbulent once again.

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE, EXHIBIT “B”

After twenty-seven years of medical practice, when Dr. P** was 65 years old, he and his family would uproot themselves and start over, yet again. Uruguay’s political and economic environment was deteriorating—an unsettling and all-too-familiar situation for Dr. and Mrs. P**. Their eldest son left for Canada, and their second son left for the United States. When the third son announced he, too, was leaving for Canada, Dr. and Mrs. P** decided to pack up and leave, as well.

People said they were crazy to emigrate once again and try rebooting their careers at such advanced ages. Too late, they were advised. Better, the advice went, to stay put, visit their children in North America from time to time, and wait for better times in Uruguay. Mrs. P** emigrated first; Dr. P** followed later.

They knew that Dr. P**’s pension and savings in devalued Uruguayan pesos would be nearly worthless in Canada. So, they knew also they would have to work upon arrival to earn a living and qualify, eventually, for Canadian pensions. (They didn’t want to burden their children, who were just beginning their respective careers.)

Dr. P** delayed leaving Uruguay for two reasons. First, he wished to qualify for his admittedly devalued pension. Second, he needed time to pass the exhaustive Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) examination that foreign medical graduates must pass in order to practice in the United States or (at the time) in Canada. Fortunately, Dr. P** had already taught himself to read and write medical English, so he was able to pass the ECFMG the first time he took it.

Dr. P** was now legally entitled to practice medicine in Canada, but only in a government hospital under permanent supervision of doctors who had done medical internships and residencies in Canada. Only those doctors who had completed medical internships in Canada were eligible to have private practices, as he had had in Uruguay. And so, he worked at a VA hospital. At least it was medicine and an income.

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE, EXHIBIT “C”

A year later Dr. P** declared that it was too depressing to work at the VA hospital, where he primarily provided end-of-life care for World War veterans. He wanted to have a private practice once again, where he could care for adult patients of all ages and medical conditions. But that would require him to undergo an internship—the brutal yearlong gauntlet generally reserved for 20-somethings just finishing med school. He wanted what he wanted. So, in his late 60s, when most doctors have either retired or are thinking about it, he became the oldest medical intern in Canadian history.

After completing his exhausting year of internship, he and Mrs. P** moved to British Columbia, where two of their sons had relocated. Now in his late 60s, he set up a brand-new private practice. He practiced family medicine there for the minimum of 10 years needed to qualify for a Canadian pension. Then, in his late 70s, he was finally able to settle into a well-earned retirement. He died at age 82, having made a meaningful net financial contribution to the Canada Pension Plan—ten years of payments, five years of receipts.

IT’S NEVER TOO LATE, EXHIBIT “D”

In the 1930s, Mrs. P**’s parents had sent her to Lausanne, Switzerland, for secondary school to escape Germany’s oppressive Nuremberg Race Laws. She was fluent in German, French and English while in Europe, and then in Uruguay, she learned and became fluent also in Spanish. Before going to Uruguay, she and her sister worked in England as tutors for the Kindertransport—the rescue program for Jewish children sent to England by their desperate parents in Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia.

For most of their years in Uruguay, Mrs. P** was a homemaker who also managed the billing of Dr. P**’s medical practice. Passionate about reading, in the mid-1960s, Mrs. P** attended the University of Uruguay’s School of Librarianship, completing its two-year degree program in 1966. Afterward, she worked as the librarian for an international organization. In the early 1970s, she made her move from Uruguay to Canada. But in-between, she stopped off in the U.S. for a year to obtain a Master’s of Library Science—an essential credential for her to work in Canada. In Ontario, now in her mid-50s, she embarked upon a new career as a corporate librarian. After their move to British Columbia, she became Chief Librarian of a public library. She passed away after a 90-year life well-lived.

And so, when my advisees tell me that they are too old and that life has passed them by, I tell them of Dr. P**. And now, I will now tell them also of Mrs. P**. My message in telling you this story has always been simple: “If you’re breathing, there’s still time.” Pass this along to anyone who might need a reminder of that simple fact.

THE KINDERTRANSPORT

The essay above notes that my friend’s mother, having escaped from Nazi Germany in 1939, worked for a time as a tutor in England—teaching the children of the Kindertransport. To understand better the environment in which she worked, I recommend the 2023 biopic, One Life. Sir Anthony Hopkins plays Sir Nicholas Winton—an Englishman who was instrumental in bringing hundreds of children to Britain as refugees and whose work went largely unheralded until late in his life.

When my wife and I adopted a four-year-old girl in our mid-fifties, people asked us if we really wanted to be parents of a teenager in our sixties. We said we did. My lawyer, who gave birth to twin boys when she was 45, warned us that people would mistake us for our daughter's grandparents. She was right. I wish that once, just once, we could be mistaken for our granddaughter's parents but it really is too late for some things.

Thanks for the encouragement... As a 50+ yo medical student, the oldest in my cohort, somewhat jaundiced about the profession I've chosen... I went to ED myself with a migraine recently for the first time ever, my local hospital, they tried to do medical tests on me without my knowledge or consent, and couldn't even get the administration of aspirin right... And I'm supposed to tell patients they should trust us??? I certainly wouldn't trust them with my cat given my patient experience...