Lemons to Lemonade

Turning grief to flourishing

Next week, Bastiat’s Window will veer back toward economics, politics, science, ethics, culture, etc.—less of me, and more of the world around us. But today, we offer one more personal account, as promised last week.

My most recent post, 2026 and the Return of Bastiat’s Window, was a mea culpa for this newsletter’s long absences since my wife died in June—and a promise to return in 2026 to frequent postings. That post noted that my absence resulted not from some paralytic sadness, but rather from my relentless building of a new life. My outlook has been upbeat and my activities mostly joyful. In private correspondence, some readers asked me to explain, in part to offer ideas on how they might successfully wend their way through grief and loss. This post does so.

In sum, the activities that crowded out my writing in recent months included: (1) Making ritual of mundane activities, (2) Learning from silence, (3) Turning grief into flourishing, (4) Entertaining and being entertained, (5) Reconnecting with old friends and family, (6) Making every meal a feast, and (7) Decluttering. My particular activities won’t work for everyone, but it would please me greatly if some readers find their own consolation in what I write here.

As I’ve told various grieving souls in recent months, sadness requires no effort, whereas happiness demands work, diligence, and discipline. This thought underlies all my actions over the past seven months. Here are some ways I have striven to make lemonade out of a lemon of a year.

[1] Making ritual of mundane activities

While I’m not obsessively neat, keeping the house tidy has assumed the status of sacred ritual. Before the going to bed, dishes are in the washer and objects are placed in their proper places. In the morning, before my coffee is ready, the bed is made, the lights illuminated, and the blinds opened. Keeping the house orderly consumes a lot of time as going from two people to one deprives the household of specialization of labor and economies of scale in daily tasks.

In the Zen Buddhist practice of “samu,” mundane physical work—cleaning, sweeping, gardening—becomes religious ritual. A classic Zen saying is “Before enlightenment, chop wood, carry water. After enlightenment, chop wood, carry water.” Equivalently, the Bible and later Western commentaries speak of wisdom coming from “hewers of wood and drawers of water.”

In 2014, Admiral William McRaven gave a commencement address that became a bestselling book: Make Your Bed: Little Things That Can Change Your Life...and Maybe the World, based on U.S. Navy SEAL training. McRaven’s premise is that small acts, such as beginning the day by making one’s bed, set the stage for contentment and success throughout the day. (The first 44 seconds of this video contain this message, though the whole speech is worth hearing.)

I’ll add that an inordinate amount of time in the early months was spent on paperwork—managing my wife’s estate and such. While those tasks were not particularly joyful, getting them done in timely, orderly fashion made it possible to enjoy the enjoy other activities.

[2] Learning from silence

When my wife died, I found myself living in quieter surroundings than I had ever known in my life. To myself, I vowed from the start that, somehow, I would make something positive of this newfound quiet. An obvious activity was to read. She and our son had left me a stack of books, and I picked one—Aflame, by Pico Iyer—solely because I liked the cover. Somehow, I failed to notice the subtitle: “Learning from Silence.”

Pico Iyer is a travel writer, but in recent years, he has taken his skills in that genre and turned them inward, carrying readers on journeys through his own psyche. Aflame explains how Iyer took a profound loss and turned it into a positive. In his case, he watched his home in Southern California burn to the ground, along with most of his worldly possessions. He vowed to himself—as I did after my wife’s death—that he would not succumb to grief but, rather, would learn from the newfound quiet around him. In Iyer’s case, he checked into a spare cabin at a Catholic monastery in the splendor of California’s Big Sur coast. After reading a few chapters, I told my son that the book described my own new life. The later pages offered wisdom on how to profit from adversity and loss.

[3] Turning grief into flourishing

In November, a scholar of religion recommended yet another book, Imagining the End: Mourning and Ethical Life, by philosopher and psychoanalyst Jonathan Lear. In an early passage, Lear seeks to explain why humans “spend time mourning, rather than just find another and move on”:

The Freudian answer, implicit in his work, is that it is characteristic of us as erotic creatures to come to life when a loved one dies. We get busy emotionally, imaginatively, and cognitively and at least try to make sense of what has happened by creating a meaningful account of who the other person was, what the relationship has meant, and how it continues to matter. We mourners, through our suffering, transform what would otherwise be a mere change into a loss, by which I mean the special emotion-filled way we create and maintain an absence in the world. We maintain this absence by keeping emotions, memories, and imagination active, by keeping the loss present to mind.

The world’s most iconic example may be Shah Jahan’s construction of the Taj Mahal in memory of his wife, Mumtaz Mahal. My own version has been promoting my wife’s artistic legacy—to keep her paintings alive in the minds of others. (Our son said I’m playing the role of Theo van Gogh to Vincent.)

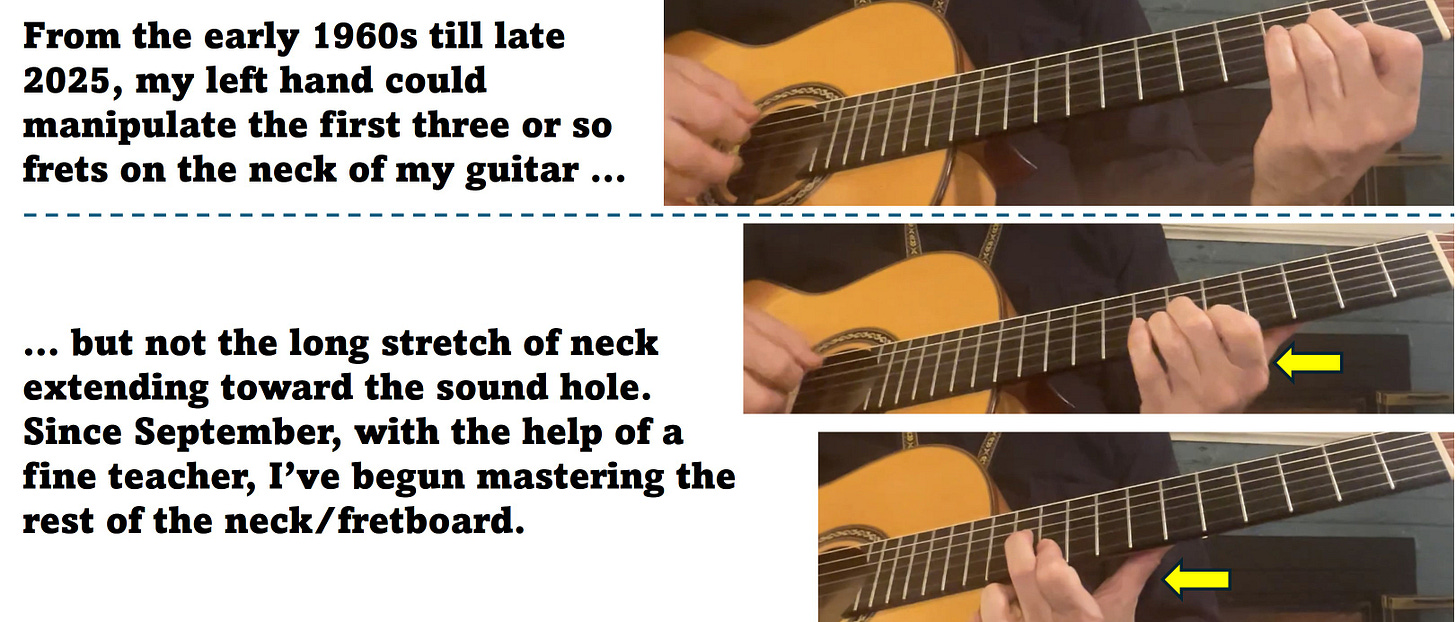

Lear goes on to describe how much of human flourishing derives from grief and our desire to derive positive good from loss. In my case, that has taken the form of music lessons. I’ve been a pianist and guitarist, sometimes semi-professionally, since age 5. But there were certain skills I never acquired until recent months. First, my ability to sing was nil; my voice was weak, scratchy, and off-key. Since June, I’ve studied voice under a masterful teacher and now give public performances (e.g., at art gallery openings). (Here I am singing “Adieu Foulard” a few months ago.) Second, while I played guitars in bars and restaurants for many years, my left hand was always tethered to the top of the fretboard—unable to navigate the lower reaches of the neck. Thanks to the assistance of another masterful teacher, I’ve begun to conquer those previously unexplored regions of the guitar.

Here’s a three-minute demo. Whenever my left hand wanders down the neck toward my right hand, I’m doing something I could never do before.

By the way, Jonathan Lear’s book also contains a really striking take on the meaning of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Read the book for that, alone. (The song I perform here also dates from the Civil War.)

[4] Entertaining and being entertained

I determined that my house would be remain a welcoming place for visitors, so I’ve made it a point to host frequent events for friends, family, and neighbors. Perhaps the most memorable event was a party attended by fourteen of my amiable and erudite college friends. When others have invited me for meals or for out-of-town visits, I’ve invariably accepted. I’ve attended a lengthy series of concerts and other public events.

[5] Reconnecting with old friends and family

“Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind?” So asked Robbie Burns in Auld Lang Syne. His question was rhetorical. Of course, he implies, one shouldn’t forget those from long ago. And so, in the past seven months, I have been reconnecting with (and in some cases visiting) friends and relatives I’ve not seen in 20, 30 or even 50 years. There is something magnificently restorative about doing so.

In Auld Lang Syne, the narrator addresses one long-ago friend in particular. He says that as children, they picked daisies together in the fields and paddled together from dawn till dusk, but then great seas and many steps came between them across the years. At the end of the song, they are together once again and share a “cup of kindness.” In one case—a newly renewed friendship of the greatest depth—I can scarcely recite those words without my voice cracking and tears rolling. This particular case of renewal confers an almost indescribable strength and joy.

[6] Making every meal a feast

Cooking for one can be a source of depression or of joy—your choice. For the sake of my soul, I consistently choose the latter. As often as possible, one’s meal should be tasty and visually appealing. It need not be complex. Here, for breakfast, I made a simple bowl of grits (blended white corn and blue corn), with a New Mexico chili-based sauce, topped off by a poached egg and browned butter. I made sure to serve it in a festive bowl, with an attractive place setting. One need not be a great chef to turn a simple, solitary meal into a source of inspiration. It just takes a bit of work.

[7] Decluttering

I’ve spent months and months thinning my possessions. Over the course of a lifetime, most of us invariably gather too many baubles and documents. Thinning their ranks and donating the extraneous ones to others offers a remarkable quantum of healing. Decluttering expert Marie Kondo suggests retaining only those objects which “spark joy.” And, at least for me, far greater joy lies in one treasured possession than in a dozen. My primary criterion has been to keep those objects that are attached to treasured memories and to send the others on their way.

Since June, dear readers, these are the activities that have infringed upon my writing time. Hence, the paucity of Bastiat’s Window posts over the past seven months. I’m grateful for the patience you have shown me, and I’m back.

Here’s a recording I made back in 2022 of Auld Lang Syne, illustrated by one of my late wife’s paintings:

Have you read much Neville Shute? His book “Round the Bend” made a particular impression on me as far as doing the small things well.

Retirement, I have found, is a grief of sort unto itself. No comparison to losing a spouse, but I found your thoughts to be helpful as I walk my way through the first six months of retirement, after working 50+ years...thank you for sharing this...