Lincoln from Chaucer, Pesci and Grampa, Marley and Burns and the King and Picard

Abraham Lincoln uses AI to speak micro-varieties of English. Fake album cover recalls the real musical connection between Joe Pesci and Jimi Hendrix. Robert Graboyes speaks 18th century Lowland Scots.

Today, we break from tariffs, politics, and such to return to another favorite topic of Bastiat’s Window—the burgeoning possibilities of artificial intelligence. Today’s AI magic involves the astonishing advances in machine translation—in particular, the ability to do instantaneous translations into vast numbers of micro-varieties of English.

Long before I took my first course in economics, I majored in English literature, with aspirations (unfilled thus far) to be a fiction writer. Half my focus was on writers of the Southern Renaissance. (The other half was Latin-American literature in translation.) In particular, I was fascinated by the Southern authors’ mastery of regional dialects. Writers like William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Zora Neale Thurston could write brilliant dialect because they had been immersed in it from birth. In the hands of outsiders, however, it’s easy for dialect to degenerate into horrors such as the dreaded Hollywood Southern—where everyone from south of the Mason-Dixon Line speaks like Scarlett O’Hara. AI offers the possibility of much better, much less labor-intensive production of dialect.

In 1997, the arrival of Babelfish.com was remarkable. Free of charge, one could quickly generate translations from English into French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and Japanese and back. The output was awkward. I used to play a little game where I would translate a passage from English into, say, French, and then translate the French back into English. After two or three rounds of back-and-forth, the message would become surreal and unrecognizable. With today’s programs, such as Google Translate, the back-and-forth is much more stable, as the translator has become adept at idioms and other odd turns of speech. Nowadays, Google Translate offers almost 250 languages. But these translations represent standard versions of these languages—say, spoken by newscasters. In contrast, large language models (LLMs) like Grok and ChatGPT go far beyond, as I’ll show below, using Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address as an example. Let’s start with the original:

FAR ISLAND AND NEAR ISLANDS

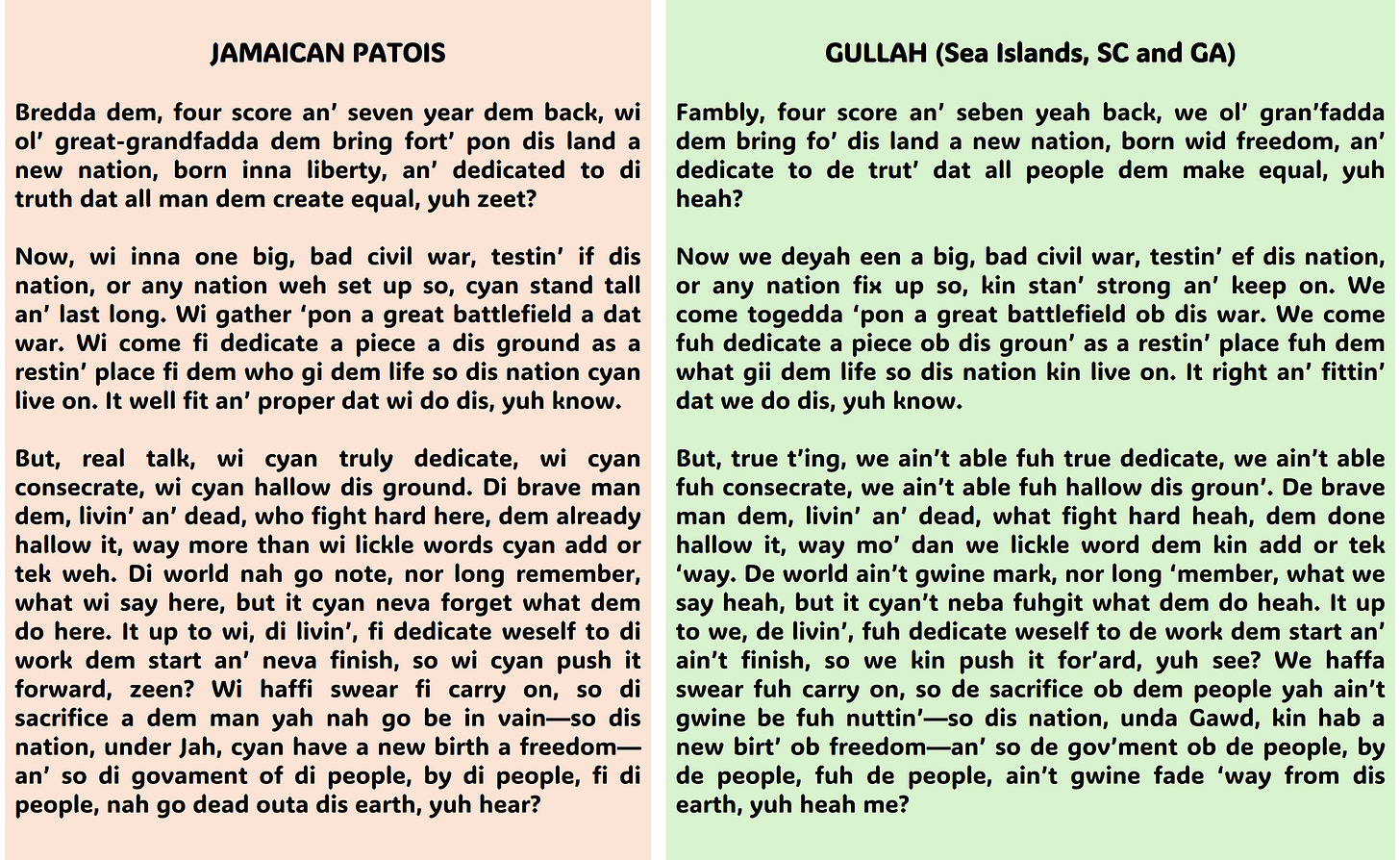

Last week, my wife and I watched the Hulu miniseries A Thousand Blows, a fascinating historical fiction based on two aspects of 1880s East London—the brutal, illegal sport of bare-knuckles boxing and the all-female Forty Elephants crime syndicate. Two characters were recent arrivals from Jamaica and spoke with a lilting Jamaican Patois that almost rose to the level of music; and in Bob Marley, it did exactly that. The Jamaican version reminded me of the Gullah/Geechee Creole Language that still exists on the Sea Islands off of South Carolina and Georgia. (Gullah was Justice Clarence Thomas’s first language, and English his second.) So, I asked ChatGPT to translate the Gettysburg Address into Jamaican Patois and into Gullah, and here’s the output:

I showed the Patois to someone from Jamaica, and she told me it was a quite accurate rendering of their speech patterns. To my outsider’s eyes, the Gullah version seems quite faithful to the diction found online in De Gullah Nyew Testament, which I’ve enjoyed reading for years. In addition to the output, ChatGPT explains—often in great detail—how it made its choices of wording and rhythm. Amidst other information on the app’s word choices, ChatGPT noted:

“Here’s a rewrite of the Gettysburg Address in Jamaican patois, keeping the spirit and structure intact but infusing it with the rhythm and flavor of Jamaican dialect … … This version aims to capture the solemnity and purpose of Lincoln’s original while using the vibrant, expressive style of Jamaican patois. Let me know if you want any tweaks!”

The programs can be surprisingly cheeky, so when I responded with “Wonderful,” it responded:

“Big up, glad yuh love it! If yuh want more vibes like dis or anyt’ing else, just holla!”

LOWLAND AND HIGHLAND

Creole languages of the Caribbean and Atlantic Seaboard U.S. are infused with bits of grammar and vocabulary of their speakers’ ancestral African languages. But there are also relics of Scottish and Irish speech from contact with slaveholders and others. I asked ChatGPT to travel across the Atlantic and across the centuries to the Lowland Scots of Robert Burns (1759-1796) and to the working-class Glaswegian Scots (Glesga Patter) of today:

And, for good measure, here’s my own voice recording of Lowland Scots version, in the best accent I can do. Readers—and especially Scottish readers—are welcome to weigh in on how I did. (This is not AI-generated. Just me speaking into a microphone.)

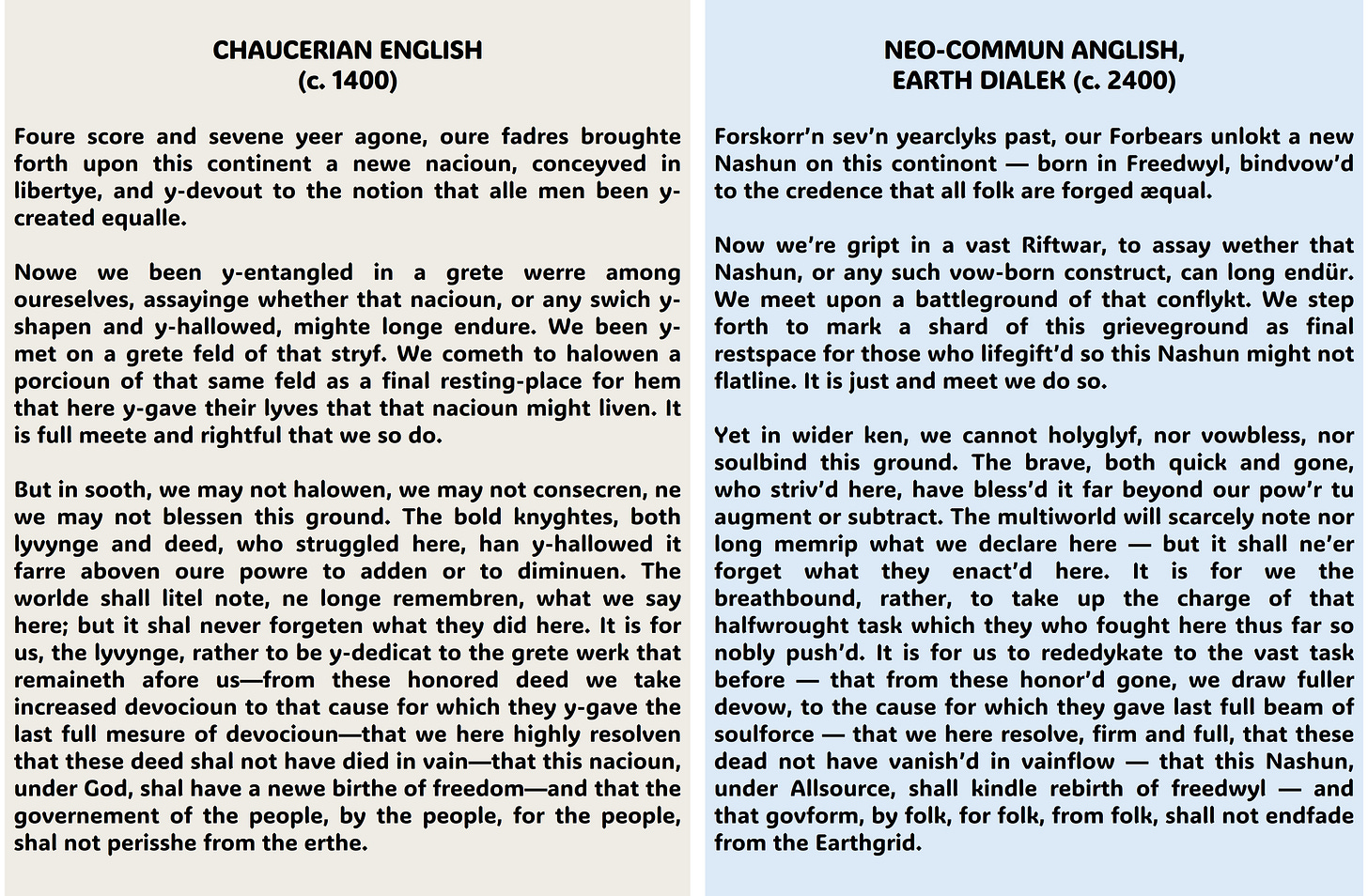

BACKWARD AND FORWARD

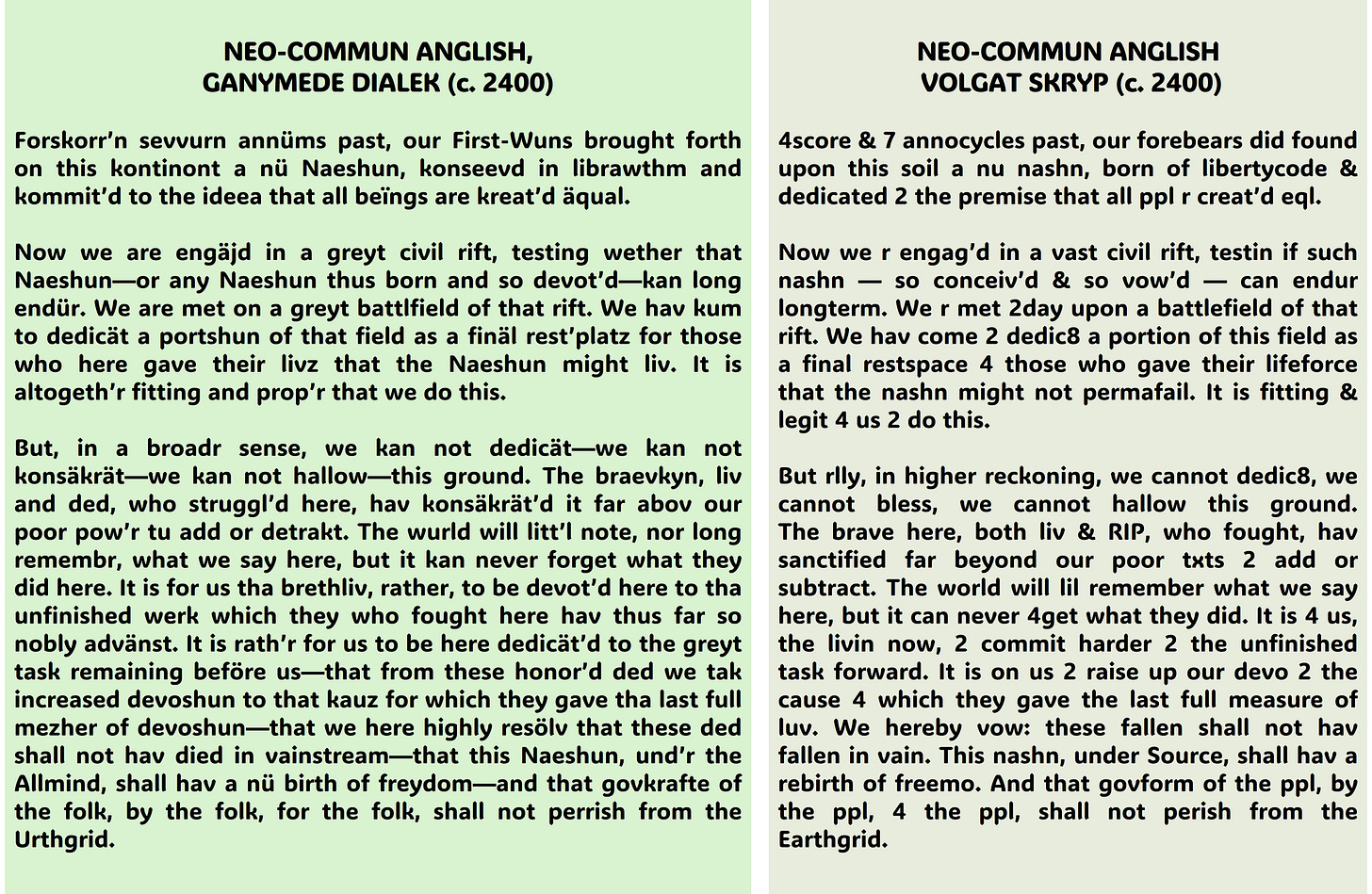

Next, I wanted to travel further backward in time and into the future—to the eras of Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343-1400) and of Jean-Luc Picard (2305-c. 2402). In the latter case, I asked it to imagine a version of English after evolving 375 years from today’s English—as distant from our eyes and ears as English from the Renaissance. I specifically asked for modest changes in vocabulary and it gave me “grieveground” and “Riftwar.” Orthographic dryft gave us “Forskorr” and “conflykt.” Our slang (e.g., “flatline” “soulforce”) has become our descendants’ standard vocabulary. Afterward, I asked for two additional dialects of English from that future time, so I named this one “Earth Dialek.”

In Picard’s time, mankind is spread far and wide across myriad solar systems. So, I also chose to include the dialect prevailing on Ganymede—the largest planetary satellite in Earth’s Solar System and the home of Robert Heinlein’s Bill Lermer. I also included the Volgat Skryp (Vulgate Script) version of English used for ease of communication with the commun ppl; it incorporates abbreviated forms that originated with late-20th- and early-21st-century text messaging.

OVER HILL AND DALE

Back on Planet Earth, 21st century, I asked for two other dialects that interest me. First is Tok Pisin (Talk Pidgin) spoken in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Like Jamaican Patois and Gullah, Tok Pisin is an English-based Creole language, though far more remote from Standard English. Sound it out, and you begin to hear the connections. “Planti yia” = “Plenty years.” “Strongpela bilip” = “Strong fellow believes,” though -pela has mostly lost the meaning of -fellow and has simply become a grammatical marker for adjectives. Second is the dialect of the Yorkshire Dales—familar to Americans from the Channel 5 (UK)/PBS (US) series All Creatures Great and Small.

THE KING’S ENGLISH AND THE QUEENS ENGLISH

And here, we’ll get more specific. First is the Gettysburg Address as if written and delivered by the King—Elvis Presley. Second is the speech written in the style of someone from Queens, New York (from whose dominion I rescued my dear wife long ago and brought her South). Joe Pesci is from New Jersey, but ChatGPT mentioned him as an exemplar of the stereotypical New York City accent, citing My Cousin Vinny and Goodfellas.

OLD ENGLISH

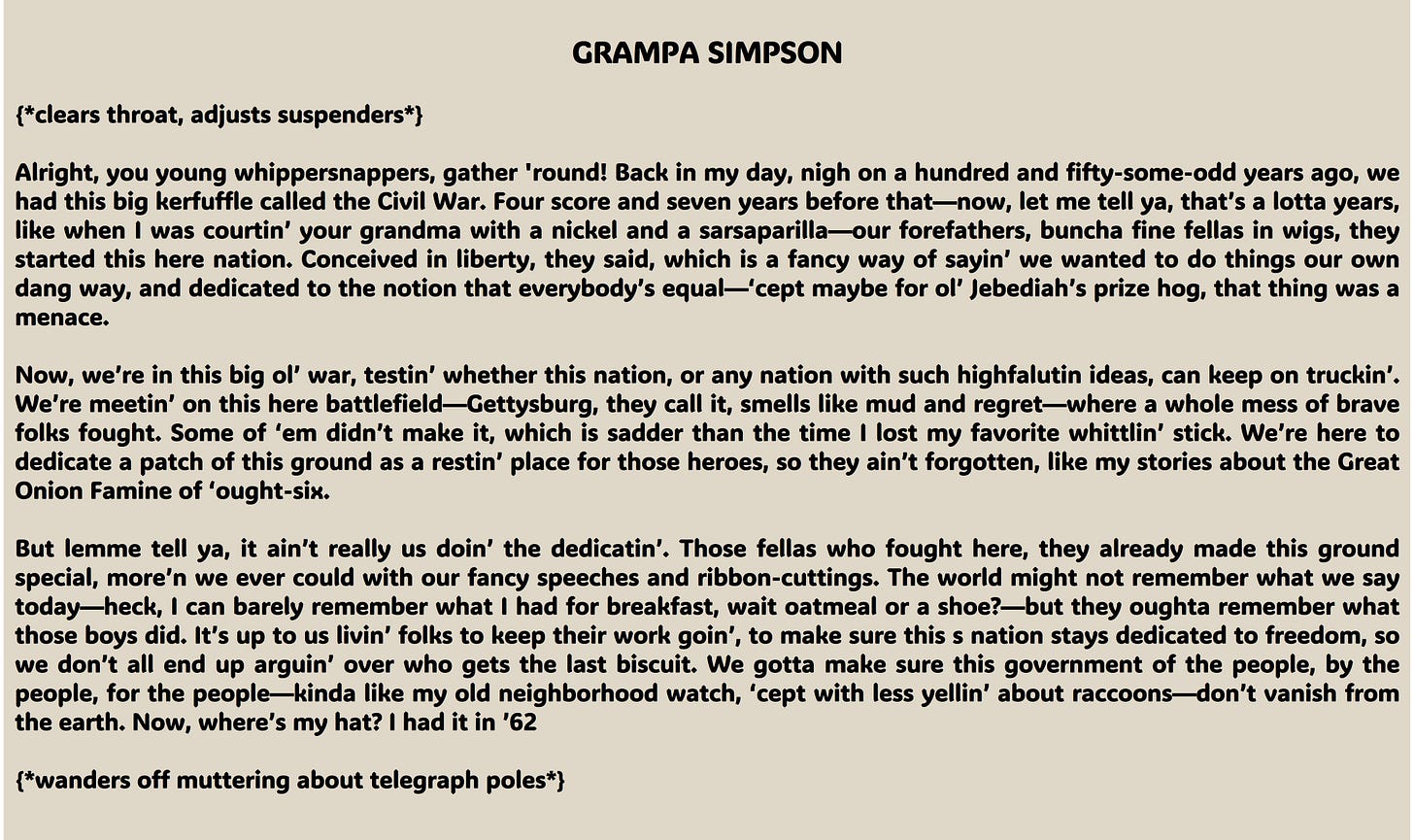

For one more hyper-specific version, I asked ChatGPT to give me the Gettysburg Address as if written and delivered by Grampa Simpson. I also asked for a picture of him delivering the speech and the first paragraph in the graphic style of the opening credits of The Simpsons.

Here’s Grampa’s complete version, complete with trailing off into confusion at the end:

Finally, ChatGPT gets rather garrulous and tangential at times. After discussing Joe Pesci’s New York accent with me, the app asked me out of the blue whether I knew that he had been a professional guitarist before he was an actor. I said I did know that, and it shared some details of his music career—especially his time with with Joey Dee and the Starliters of “Peppermint Twist” fame.

I then told ChatGPT that it had forgotten the single most interesting fact of that history—that after Joe Pesci left the Starliters, one of his later replacements was Jimi Hendrix. The app agreed and shared some details about that connection. I asked whether Pesci and Hendrix ever met, and it gave detailed reasons why they probably never did. I closed by asking it to design a vintage album cover of an imaginary collaboration—a bit scuffed up after 60 years of handling, but otherwise well-preserved.

Bob, A truly unique post and fun to read. Thanks for keeping things light, and fascinating. Now, back to the ideology wars...........................

Rick

Oh, I enjoyed this SO much. My verdict on the Lowland Scots accent (expertise based on multiple re-reads of the Highlander series ;-) heh heh) is TOTALLY ACCURATE and even if not so - how very enjoyable to listen to you growling and rolling your r's. Thank you so much for your always very fun essays.