Paid subscriptions are a tremendous help in keeping Bastiat’s Window going. Of course, free subscriptions are also deeply appreciated. Sharing Bastiat’s Window articles helps to expand the subscriber base. And sharing this particular piece will remind readers of the sacrifice of one particular U.S. Marine.

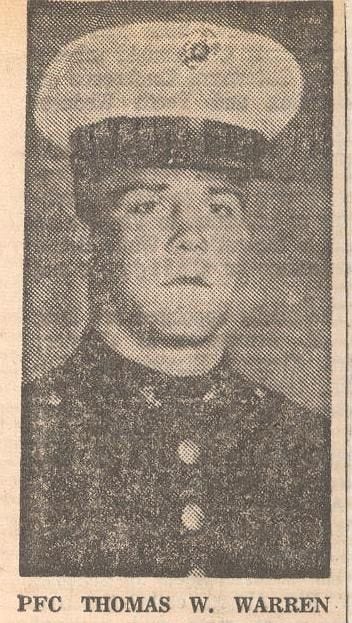

From Fall 1967 to Spring 1968, for no obvious reason, a 12th-grade football hero extended warmth and tolerance to a flyspeck of an 8th grader in the halls of Petersburg High School. I was the flyspeck. The football hero was Tommy Warren, who would graduate in June, enter the U.S. Marines, attain the rank of private first class, and die in Quang Nam province, South Vietnam, five months after I last saw him. My recollection (perhaps imperfect) is that of a somber voice (probably Principal Ed Betts) announcing his death over the loudspeaker, followed by anguished faces in the hallway.

The year before, Tommy would regularly hold court in the school’s front hallway, surrounded mostly by his fellow athletes, cheerleaders, and others with those things that grant status in a high school. Somehow, I, a diminutive, decidedly non-athletic bookworm, ended up as a regular in these sessions. I don’t remember how that began, and I have no idea why Tommy made me feel welcome in that assemblage, even as he regularly rolled his eyes at my prattling.

I was precociously aware of politics and policy and was among those who greeted Vice President Hubert Humphrey that year when he arrived to campaign for president in our small town. I was also quite aware that I would be of draft age in the not-too-distant future. Hence, I was well-versed in the debates over the Vietnam War. But until November 1968, it was all an abstraction—written words and Walter Cronkite. Tommy’s death made it tangible, palpable, and raw.

Since moving to the Washington, DC, area in 2007, I’ve made it a point every few years to visit Tommy’s name on the great and quiet monument on the Mall. I always utter aloud a few words to thank him for his generosity—both to my oft-beleaguered 13-year-old self and to his country.

Today, I’m fast approaching 70 years of age, while the Tommy shown above on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website remains barely more than a child. Seeing him these many years later reminds me of a poem that hung in my English class in that very same school: A. E. Housman’s “To an Athlete Dying Young.” One passage from that work stands out when I think of Tommy:

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

Last week, I twice quoted John Keating (Robin Williams), fulminating in the 1989 film, Dead Poet’s Society. At the risk of overusing a source, I’ll share one more quote from that film—this one more hushed and poignant. Keating takes his privileged, full-of-themselves students to a set of photographs of long-dead students. He tells them:

They're not that different from you, are they? Same haircuts. Full of hormones, just like you. Invincible, just like you feel. The world is their oyster. They believe they're destined for great things, just like many of you. Their eyes are full of hope, just like you. Did they wait until it was too late to make from their lives even one iota of what they were capable? Because you see, gentlemen, these boys are now fertilizing daffodils. But if you listen real close, you can hear them whisper their legacy to you. Go on, lean in. Listen. You hear it?... Carpe... Hear it?... Carpe. Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary.

Tommy’s life, as short as it was, was made extraordinary by the events of his time. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg a century earlier, he “gave the last full measure of devotion.” And so that you, 55 years later, might know just a bit more about that devotion, here’s a description from Honorstates.org:

Thomas Wayne Warren was serving his country during the Vietnam War when he gave his all in the line of duty. He had enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. Entered the service via Regular Military. He began his tour on July 20, 1968. Warren had the rank of Private First Class. His military occupation or specialty was Machine Gunner. Service number assignment was 2436561. Attached to 1st Marine Division, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, L Company.

He was born on February 22, 1950. According to our records Virginia was his home or enlistment state and … [w]e have Petersburg listed as his city.

During his service in the Vietnam War, Marine Corps Private First Class Warren experienced a traumatic event which ultimately resulted in loss of life on November 23, 1968. Recorded circumstances attributed to: Died through hostile action … small arms fire. Incident location: South Vietnam, Quang Nam province.

Lagniappe

“Siúl a Grá” / “Johnny’s Gone for a Soldier”

The Irish folk song known in English as “Johnny Has Gone for a Soldier” was originally known as “Siúl a Grá” (pronounced “Shule Agra”). In the early 1960s, Peter, Paul & Mary performed it under the title, “Gone the Rainbow.” My mother often played the PP&M album and sang the song, accompanied by her own guitar (which I own to this day). Those early memories of the song never left me. As in the PP&M version, the song is typically sung in the voice of a woman who mourns the departure of her husband for war and who has sacrificed her worldly goods to buy him a sword.

The Irish title translates as “Go, my love” or, literally, “Walk, my love.” In some versions, Johnny’s ultimate fate is unknown; he has gone, but we do not know whether he might return.

For many years, I worked part-time as a musician. During the pandemic, to occupy myself during the lockdowns and to stay connected with friends, I gave musical lectures and performances on Facebook. For Memorial Day 2020, I reworked the lyrics of “Siúl a Grá” to put them in the third person and to indicate a cold finality to the story. Johnny will never return to his inconsolable wife. I wrote a new first verse, edited some lines throughout, and altered the song’s final line to reflect this finality. I did so to honor those, like my friend Tommy Warren, who sacrificed their lives so that I would not have to—and to honor those who fought and served alongside them. The video is 7 minutes, 39 seconds long and consists of a brief lecture at 0:00, a vocal version at 2:11, and a slow jazz improvisation from 4:48 on.

That's a very beautiful rendition. Today, I was at Land's End in San Francisco for the annual commemoration at the USS San Francisco memorial. At the Battle of Guadalcanal, Admiral Daniel Callaghan (San Francisco native and graduate of St. Ignatius High School), took the San Francisco right into a fray with a larger Japanese squadron. His second in command, Cassin Young, told him, "This is suicide." Callaghan replied, "Yes, but we have to do it." The San Francisco took some big hits, and these two were among the many killed. The Allies won the battle, which was an important turning point in the war.

It was an honor to take part by handing out doughnuts and coffee and other goodies to the veterans and other participants (as part of a DAR volunteer hospitality crew). What valor.

It's one thing to talk about the sacrifices our veterans made for our freedoms.

It's another thing entirely to meet someone who lost a friend or a family member and has lived with that loss every day of their lives.

Mine came the day I met a man whose father was lost on the USS Indianapolis. He looked me in the eye and said: "I never knew my father."

Over the years I learned that as a result he knew more about his father than most of us do.

I also came to realize that you can never fully understand the loss and grief, but at least you can get a glimpse of what it cost them.

Robert - Thank you for this article. It is important to remember those young lives. KenMc