I meant to post this on Monday—Memorial Day—but other aspects of life got in the way of my writing this week. So with apologies, here’s a slightly belated, very personal recollection of one particular U.S. Marine who, in Lincoln’s words, “gave the last full measure of devotion” to his country. This is a lightly edited version of my post from Memorial Day 2023. At that time, most of today’s Bastiat’s Window readers had not yet subscribed, so I hope long-time readers don’t mind seeing it once again.

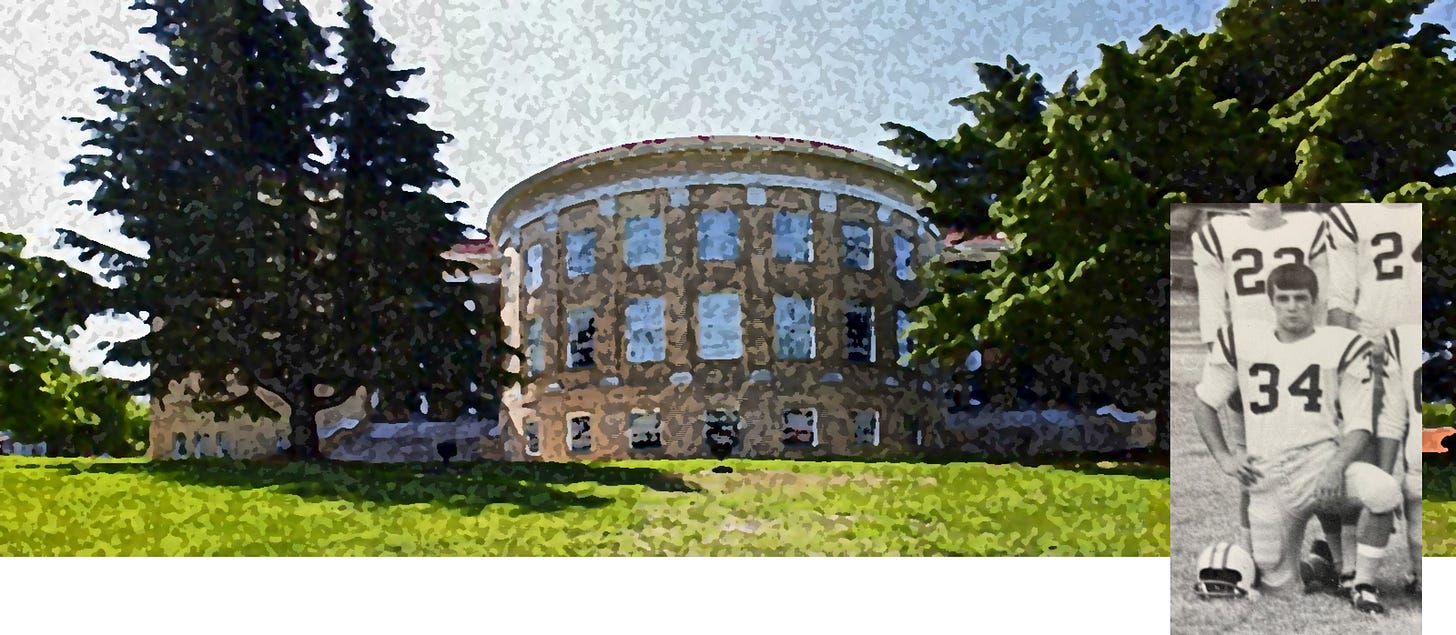

From Fall 1967 to Spring 1968, for no obvious reason, a 12th-grade football hero extended warmth and tolerance to a flyspeck of an 8th grader in the halls of Petersburg High School. I was the flyspeck. The football hero was Tommy Warren, who would graduate in June, enter the U.S. Marines, attain the rank of private first class, and die in Quang Nam province, South Vietnam, five months after I last saw him. My recollection (perhaps imperfect) is that of a somber voice (probably Principal Ed Betts) announcing Tommy’s death over the loudspeaker, followed by anguished faces in the hallway.

Tommy’s service was in keeping with the deep and honored military tradition that envelops and permeates Petersburg, Virginia. I exist only because my father was drafted in 1941 and sent south from Philadelphia to nearby Camp Lee (now Fort Gregg-Adams). When Dad and Mom met that year, some old-timers in town would still have remembered seeing Abraham Lincoln riding on horseback to his April 3, 1865 meeting with General Grant—a mere four-block walk from our school. Lincoln viewed the rebel earthworks, strewn with the dead, and a century later, we kids still played on the eroding remnants of those melancholy embankments. Our high school yearbook was called The Missile, named (I believe) for the projectiles fired during the War of 1812.

In the brief months that I knew him, Tommy would regularly hold court in the school’s front hallway, surrounded mostly by his fellow athletes, cheerleaders, and others with those things that grant status in a high school. Somehow, I, a diminutive, decidedly non-athletic bookworm, ended up as a regular in these sessions. I don’t remember how that began, and I have no idea why Tommy made me feel welcome in that assemblage, even as he regularly rolled his eyes at my prattling.

I was precociously aware of politics and policy and was among those who greeted Vice President Hubert Humphrey that year when he arrived to campaign for president in our small town. I was also quite aware that I would be of draft age in the not-too-distant future. Hence, I was well-versed in the debates over the Vietnam War. But until November 1968, it was all an abstraction—written words and Walter Cronkite. Tommy’s death made it tangible, palpable, and raw.

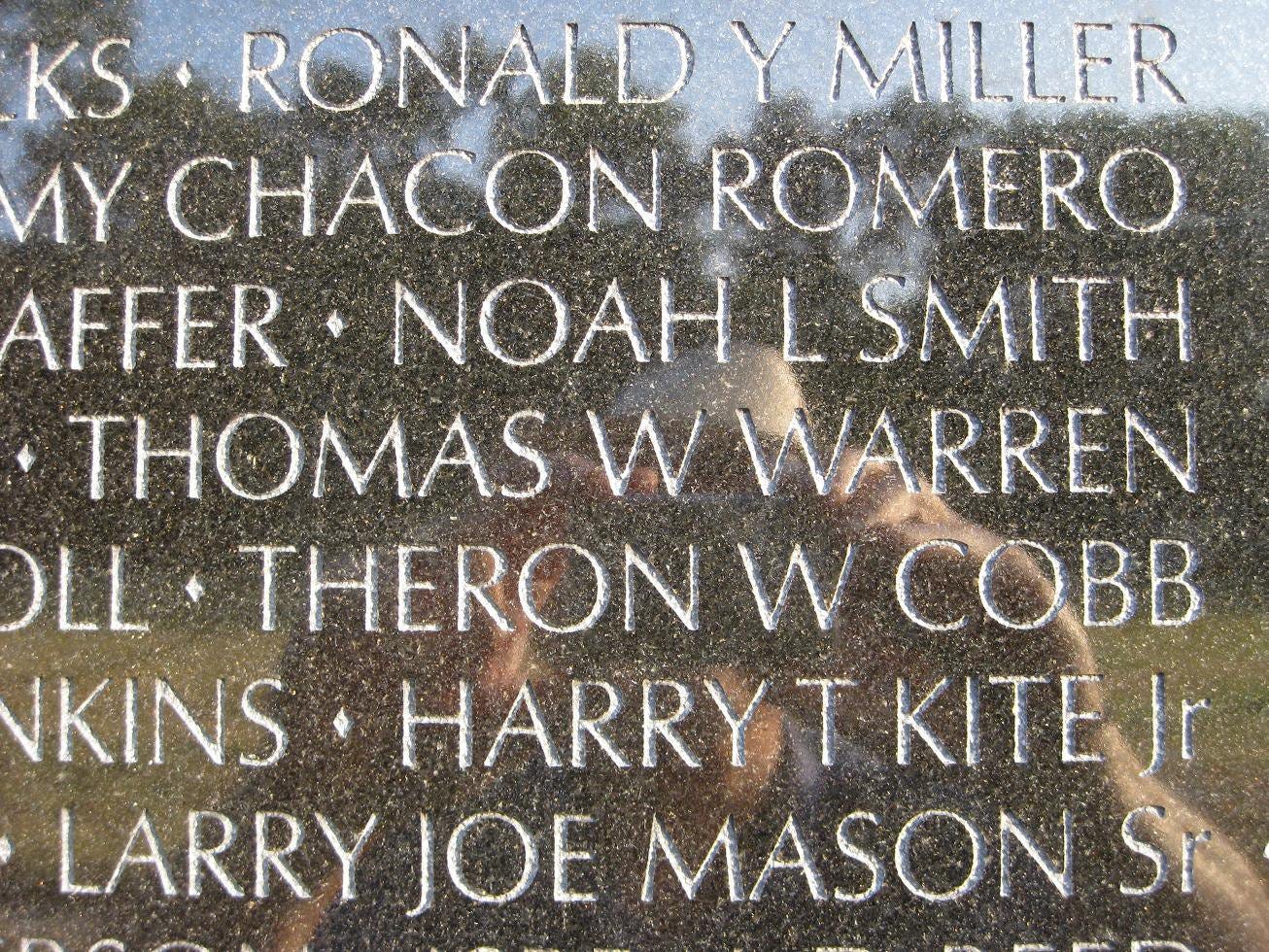

Since moving to the Washington, DC, area in 2007, I’ve made it a point every few years to visit Tommy’s name on the great and quiet monument on the Mall. I always utter aloud a few words to thank him for his generosity—both to my oft-beleaguered 13-year-old self and to his country.

This year, I reached 70 years of age, while Tommy, shown above on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website, forever remains barely more than a child. I have finally achieved the Psalmist’s pronouncement that, “The days of our years are threescore years and ten,” while Tommy never managed even onescore. Seeing his image these many years later reminds me of a poem that hung in my English class in that very same school: A. E. Housman’s “To an Athlete Dying Young.” One passage from that work stands out when I think of Tommy:

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

In the 1989 film, Dead Poets Society, John Keating (Robin Williams), takes his privileged, full-of-themselves students to a set of photographs of long-dead students. He tells them:

They're not that different from you, are they? Same haircuts. Full of hormones, just like you. Invincible, just like you feel. The world is their oyster. They believe they're destined for great things, just like many of you. Their eyes are full of hope, just like you. Did they wait until it was too late to make from their lives even one iota of what they were capable? Because you see, gentlemen, these boys are now fertilizing daffodils. But if you listen real close, you can hear them whisper their legacy to you. Go on, lean in. Listen. You hear it?... Carpe... Hear it?... Carpe. Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary.

Tommy’s life, as short as it was, was made extraordinary by the events of his time. As Lincoln said at Gettysburg, he “gave the last full measure of devotion.” And so that you, 56 years later, might know just a bit more about that devotion, here’s a description from Honorstates.org:

Thomas Wayne Warren was serving his country during the Vietnam War when he gave his all in the line of duty. He had enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. Entered the service via Regular Military. He began his tour on July 20, 1968. Warren had the rank of Private First Class. His military occupation or specialty was Machine Gunner. Service number assignment was 2436561. Attached to 1st Marine Division, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, L Company.

He was born on February 22, 1950. According to our records Virginia was his home or enlistment state and … [w]e have Petersburg listed as his city.

During his service in the Vietnam War, Marine Corps Private First Class Warren experienced a traumatic event which ultimately resulted in loss of life on November 23, 1968. Recorded circumstances attributed to: Died through hostile action … small arms fire. Incident location: South Vietnam, Quang Nam province.

I hope it’s appropriate for this civilian to say, “Semper Fi, my friend.” To paraphrase another old Irish song of war, Tommy, we hardly knew ye.

“SIÚL A GRÁ” / “JOHNNY’S GONE FOR A SOLDIER”

The Irish folk song known in English as “Johnny Has Gone for a Soldier” was originally known as “Siúl a Grá” (pronounced “Shule Agra”). In the early 1960s, Peter, Paul & Mary performed it under the title, “Gone the Rainbow” (video below). My mother often played the PP&M album and sang the song, accompanied by her own guitar (which I own to this day). Those early memories of the song never left me. As in the PP&M version, the song is typically sung in the voice of a woman who mourns the departure of her husband for war and who has sacrificed her worldly goods to buy him a sword.

The Irish title translates as “Go, my love” or, literally, “Walk, my love.” In some versions, Johnny’s ultimate fate is unknown; he has gone, but we do not know whether he might return.

For many years, I worked part-time as a musician. During the pandemic, to occupy myself during the lockdowns and to stay connected with friends, I gave musical lectures and performances on Facebook. For Memorial Day 2020, I reworked the lyrics of “Siúl a Grá” to put them in the third person and to indicate a cold finality to the story. Johnny will never return to his inconsolable wife. I wrote a new first verse, edited some lines throughout, and altered the song’s final line to reflect this finality. I did so to honor those, like my friend Tommy Warren, who sacrificed their lives so that you and I would not have to—and to honor those who fought and served alongside them. The above video is 7 minutes, 39 seconds long and consists of my brief lecture at 0:00, a vocal version beginning at 2:11, and a slow instrumental jazz improvisation from 4:48 on.

You have written a meaningful and kind tribute to an ordinary young man that suffered an unfair fate. I am sure his family and friends appreciate someone who remembers and honors that young life long since passed. Thank you for this Memorial Day reminder. I am grateful for all of the young Tommy Warrens and saddened by their sacrifice.

What a hash our politicians—and, to be fair, behind them our people—made of the sacrifices of the great and good young men they and we sent to Vietnam. And I say that whether (as some believe) our involvement in that war was initially good and wise or (as others believe) misguided and/or wrongful from the beginning.

(I notice especially among those who dodged the draft a tendency to regard our war as wrongful, and themselves therefore as not so much cowardly as noble. John Kerry is their patron saint, but Donald Trump worships in that church.)