In Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, somewhere in the early-to-mid-1800s, the gypsy Melquíades, on his annual visit to Macondo (in the Colombian tropics), brings his friend and customer, José Arcadio Buendía, a block of ice. José Arcadio, seeing ice for the first time, proclaims it to be “the greatest invention of our time.” The essay you are reading now consists mostly of my memories of cultural and technological firsts. To readers raised in the iPhone Era, the amazement I express over PCs, emails, web searches, coffee shops, etc. will sound about as bizarre as José Arcadio’s astonishment over ice—and for exactly the same reasons. (Fun fact: the international ice trade only got rolling in the 1830s, so there’s an historical basis for this scene in the book.)

c.1962: My cousin in North Carolina said we were going to lunch at McDonald’s. I asked, “What is ‘McDonald’s?”

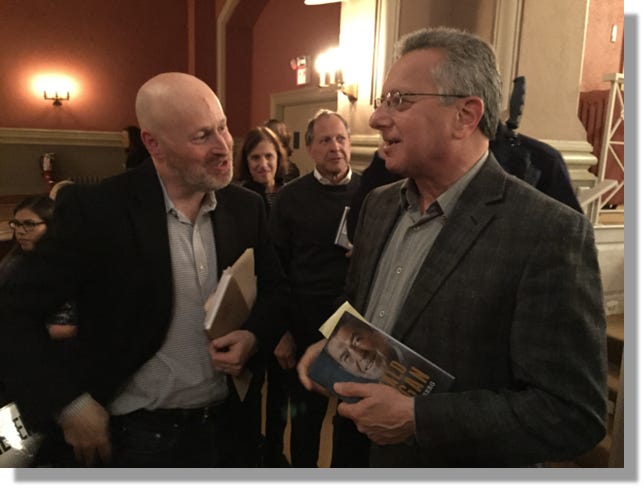

1965: At the New York World’s Fair, I made my first video call, speaking by “picturephone” to my father, who was in the adjacent room. The week before, my father’s cousin had given me a 40-year-old candlestick telephone (pictured above). Coincidentally, it would take another 40 years before Skype made the picturephone concept practicable.

c.1972: I practiced piano in the music building at the University of Virginia. A stranger walked in and offered some unsolicited advice on technique. (Briefly: imagine each note is a dimensionless point, rather than a stretch of time.) I thanked him and asked whether he was a professor. No, he said, he was in town for a concert. “Who’s playing?” I asked. He said, “I think his name is … Livingston Taylor.” I looked for a moment, felt a flash of recognition, and said, “You’re Livingston Taylor, aren’t you?” He smiled and said, “Yeah … I guess I am.” There’s a technological angle to this story, but I’ll save that for later in this piece.

1976: I was a volunteer with the University of Virginia’s film series. The student-managers were Sam, who later wrote the first two Batman movies, and Steve, who became an animator. One evening, they invited me over to Sam’s apartment to watch Orson Welles’s A Touch of Evil, which we would be showing later that week. At some point, Sam stopped the projector so we could make a snack. When he restarted the projector, of course, we hadn’t missed anything. Stopping and restarting a movie at will?! It struck me as miraculous—akin to the Biblical tale of the sun halting in the sky over Gibeon.

1978: I was briefly legislative correspondent for five small Virginia newspapers. One paper lent me a fax machine. I’d stick one sheet of typewritten paper onto a roller; the machine would spin and squeal; and I’d take a shower while waiting for that one page to transmit. By the end of my shower, the page was either transmitted or shredded by the roller.

1983: My first PC, a Kaypro II (pictured above), engendered awe among Columbia classmates and Chase Manhattan coworkers. Together, computer and printer cost around $3,500 ($10,000 in 2023 dollars). The Kaypro weighed 29 pounds, and packed up neatly, so I could occasionally take it to Chase, which did not yet provide computers to its economists. Internal memory was 64K—the size of a small Word document today. (Sounds small, but the two Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977, which photographed the giant planets and are still functioning at or beyond the edge of the solar system in 2023, each has a 69.63K computer—essentially flying Kaypros.)

Mid-1980s: Traveling in Sub-Saharan Africa, it was nearly impossible to make a call to my then-girlfriend-now-wife, Alanna. Credit cards were useless. Obtaining cash required long, tedious bank visits.

Mid-1980s: At IBM’s headquarters, a PC autonomously typed long rows of traditional, complex Japanese script. Periodically, the sentence would collapse into lean, compact modern Japanese script. It was mesmerizing, and I stared and stared.

Early 1990s: In DC, friends Charlie and Cary took to us to a new Starbucks, in a majestic old building. I asked, “What is a ‘Starbucks’?”

Mid-1990s: Friend Lou gave a lecture at the Richmond Fed. Before his talk, he borrowed one of our shared PCs to do a search and find some links. I watched, as I, who had programmed software, had no idea how to do searches or use links.

Mid-1996: Alanna and I watched a peculiar, but interesting movie (“The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T.”) from midnight to 2 AM. Afterward, Alanna said, “The kid in the film looked familiar. After discussing many possibilities, she concluded, “I think when he was older, he played the kid on ‘Lassie.’” Before 1996, Alanna would have said, “I think that when he was older, he played the kid on ‘Lassie.’” I would have said, “Maybe so,” and that would have been that. But in 1996, it occurred to me that we had a brand-new Dell PC, with dial-up World Wide Web access. So down the hall I went. Somewhere around 2:30 AM, Ask Jeeves told me that the actor was, in fact, Tommy Rettig—Jeff on “Lassie” (1954 to 1957). I also learned that Rettig had drug-related legal problems, became a motivational speaker and computer programming guru, struggled with obesity, married a 15-year-old, lived on a houseboat, and died of a heart attack just a few months before my web search. This was likely my first deep-dive into no-need-to-know computer-generated flotsam. Thanks to the IT revolution and Moore’s Law, I can share all this factual detritus with you 27 years later. And afterward, you will with zero doubt do a Google search on Tommy Rettig and learn even more needless trivia about an obscure, long-dead stranger.

Mid-1996: In a talk at the Fed, I demonstrated MapQuest. People gave me their home addresses, and up on the screen popped maps showing their houses. Audience members viewed the demonstration as if they were watching Moses turn his rod into a serpent. They were also creeped-out by the obvious loss of privacy that this new technology delivered.

Late 1996: I considered a job in Pittsburgh—a prospect that didn’t please Alanna. We visited the Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce website. Up came an old black-and-white photo of a smog-choked, soot-encrusted Hell. Alanna was horrified, and asked, “THAT’S where you want me to move?!” But almost immediately, the photo began morphing into a much newer photo of the same scene—sparkling clean vintage buildings, bright green grass, and brilliant blue sky. The Chamber clearly knew that Pittsburgh had an image problem, and they used technology and humor to deal with it up-front. This was our very first glimpse at the possibilities of computer graphics.

c.1997: At middle school, our son Jeremy’s class received a list of animals. Each student chose one animal to be the subject of a essay. Other students chose “cow,” “horse,” and “duck.” Jeremy, being our son, chose “anaplogaster.” Our first reaction was, “What the hell is an anaplogaster?” Pre-Wikipedia, pre-Google, such obscure information was still elusive. Ask Jeeves said the anaplogaster is a deep sea fish—and not much more. We did somehow find the email address of the world’s leading anaplogaster expert—at a lab off the Scottish coast. We emailed him a series of questions. Maybe four days later, he responded, apologizing for his delay in answering. He had been diving near Cyprus. It was now possible to bother total strangers across the ocean and get them to apologize to you for responding in what, the year before, would have been record time.

c.1998: Alanna, Jeremy, and I read novels together and discussed them at dinner. One week, we read The Chosen, by Chaim Potok—a relatively famous novelist. In the book, a rabbi maintains silence with his son, speaking to him only under rare circumstances. We wondered whether this custom was a purely fictional construct or if it had some basis in fact. I found Potok’s email address and asked him. The next day, he wrote back with a non-answer, but we now knew it was now possible to reach out to a famous person and elicit a quick, albeit annoying, response. I told Alanna and Jeremy I had some questions about Shakespeare and was going to email him, too.

c.1999: An Australian lab set up a remote-controlled robot, and Web visitors could enter commands to make it move around the room and pick things up. I couldn’t master the commands and only managed to topple the robot, rendering it useless for other users. The system sent angry messages about my carelessness. I did this a couple of times, from incompetence, not malice, but I did get just the slightest tingle of the perverse pleasure that hackers and cyberterrorists must enjoy.

2000: Heading to Almaty, Kazakhstan, I had an eight-hour layover in Amsterdam and decided to do a little sightseeing. Early Sunday morning, I wandered the streets and I saw a sign marked “Internet Bar”—a concept I had never heard of. I went in, rented a computer station, and checked my email. An email from my then-sleeping son said, “Welcome to Almaty!” I replied, “Actually, it’s 6 AM, and I’m in Amsterdam having a beer and French fries.” When I landed at an old Soviet airport in Almaty, I spied an ATM, stuck my card in, and was astounded when a wad of Kazakh currency poured out of the machine. In my hotel room, I called home and had a long, inexpensive conversation. Traveling the lands ravaged by Genghis Khan was now just like visiting Indiana.

Early 2000s: The Federal Reserve lent its economists cell phones while we traveled. In Idaho, I rented a car and roamed the wilderness. In the middle of nowhere, the phone rang and Alanna said “hi.” A message from the emperor of a distant galaxy wouldn’t have amazed me more.

Mid-2000s: Friend Yvonne took me 10,000 feet up into Rocky Mountain National Park. My phone rang. It was Alanna, saying the University of Richmond had called to say that I hadn’t turned in my expense receipts, and that day was the deadline. I told Alanna which purple folder held my receipts, how to format the documents, and where to fax them. 15 minutes later, it was all done, and I got my $350. I was thrilled, but I also realized, right then and there, that I would never again be entirely away from the office.

2008: I went jogging at Newport Beach, California. Mid-run, I took out my camera (not phone) and snapped a photo of myself with palm trees in the background (above). Afterward, I carefully cropped the picture to hide the fact that I was both subject and photographer. If people knew that I had taken my own photo, I thought, it would make me seem terribly vain.

2015: I posted a whimsical tweet about TV’s The Americans, and I included the handles of the show’s producers. They started retweeting and commenting, and my tweet got thousands of views. For a few years afterward, the executive producer, Joe Weisberg, and I corresponded occasionally. In 2017, I compared one of his recent scenes to an iconic scene in the film noir Rififi (1955) and suggested that if he hadn’t seen the film, he should. He never replied on that point, but the 2018 season included an episode titled “Rififi.” Coincidence?

2015: Cadillac released a great ad featuring five unlikely innovators. One was Njeri Rionge, a Kenyan hairdresser who became an international Internet CEO and venture capitalist. Lying in bed at 5:00 AM on Sunday, I found her contact info, emailed her, received an immediate response, and chatted for half an hour by email. I mentioned how impossible it had been for me to contact Alanna from Kenya in 1984. Had I not been in a darkened bedroom in my pajamas, we could have spoken by video, as easily as I had spoken 50 years earlier with my father, 10 feet away, by picturephone.

2021: In the decades since Livingston Taylor gave me a free piano lesson, I always tried to follow his advice. I don’t always do so. But when I don’t, I always remember that I’m ignoring the sage words he offered me. In 2021, I thought about how impactful his casual advice had been, hunted around for his email address, and sent him a half-century-belated thank-you note for his advice. A day later, I received a wonderfully gracious response.

Small world.

Lagniappe

That Small World in One Two-Part Chart: Take all the living things on earth, dry them out, and suck out the carbon. Then stick that carbon on a BIG scale. Looking at Chart A, the whole pile will weigh around 545.2 gigatons (Gt). Of that, 450 Gt are plants, 70 Gt are bacteria, etc. Animals account for 2 Gt—a little over 1/3 of 1% of the total. Now, Chart B, takes that 2 Gt of animal carbon and divvies it up. Around half is arthropods, which includes butterflies, spiders, barnacles, scutigeromorpha, and crawfish etouffee. Then comes fish and a bunch of other things. Humans are around 3% of animals, or a little over 1/100 of 1% of the weight of all life. Wild mammals are just a miniscule 1/1000 of 1% of life on earth, but that is of little consolation if a polar bear is eating you.

Kaypro! In the early 1980s my first husband was a grad student in molecular biology and one of the other students had a Kaypro II. They figured out some way to rig the parallel port to control various pieces of lab equipment. Nothing terribly sophisticated -- along the lines of running a magnetic stirrer for X hours and then shutting it off. But it relieved them of having to get up and go to the lab in the middle of the night. I suppose some of those guys ended up running scientific device start-ups. Bob became a truck farmer, but that's a separate story.

Re: charts A and B

So many plants! So little etouffee!