Petersburg, Virginia, from Duns Hill (1880), from Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

100 years ago today, September 14, 1922, my mother, Lois Graboyes, was born in Petersburg, Virginia. For me, at age 68, 1922 seems a good ways back, but not ancient history. But the magnitude of that time span becomes clearer when I imagine the world that existed 100 years before her birth. On September 14, 1822, James Monroe was president—the last of the Founding Fathers to hold that office. In that year, South Carolina hanged Denmark Vesey for planning a slave revolt, freed slaves founded Liberia, Charles Babbage proposed his wood-and-brass proto-computer, Edinburgh ceased public whippings, Sweden unbanned coffee, and the Rosetta Stone was deciphered. King George III had died only two years earlier.

Mom’s birth a century ago preceded the Great Depression, World War II, television, rocketry, and the discovery of both Pluto and the neutron. A century before that, the telephone, telegraph, camera, elevator, escalator, automobile, passenger railway, airplane, sewing machine, vacuum cleaner, air conditioner, and typewriter lay years in the future, as did aspirins and Coca-Cola. Our hometown was a hellscape of slavery and would host the final great battle of the Civil War 43 years later.

My field of study, healthcare, may present the starkest contrasts of all. At age 92, Mom had a near-death experience. One evening, she was using her beloved iPad to FaceTime with her grandson, an emergency physician. In the course of the conversation, he detected hints that she might be in the early stages of toxic shock; she was, and rapid response and massive doses of antibiotics saved her life. But at the time of her birth in 1922, efficacious antibiotics were no more available than iPads. Mom’s birth was only a decade past what Harvard medical school professor referred to as “The Great Divide,” when, he said, “for the first time in human history a random patient with a random disease consulting a doctor at random stands a better than 50/50 chance of benefiting from the encounter.” From the 1820s till the 1920s, medicine was largely mired in an era of “therapeutic nihilism,” when doctors often took Hippocrates’ “do no harm” to mean “do nothing.” This utter loss of professional self-confidence came about because modern science was conclusively demonstrating that 1,600 years of leeches, bloodletting, and bodily humour analysis had done much harm and little good for patients.

In 1922, F. Scott Fitzgerald branded the era “the Jazz Age,” and as a lifelong jazz fan, my mother took took pride in that designation. A century earlier, 1822 was in the Era of Good Feelings—the relatively quiet period following the War of 1812. In The Birth of the Modern, historian Paul Johnson argued that everything changed between 1815 and 1830:

“political, economic and demographic changes, all without precedent in their scale and future significance, were accompanied by powerful new currents in music and painting, literature and philosophy, some ennobling and refreshing, some sinister.”

We are as far today from my mother’s birth as her birth was from doctors in powdered wigs treating cancer and respiratory problems with tobacco smoke enemas.

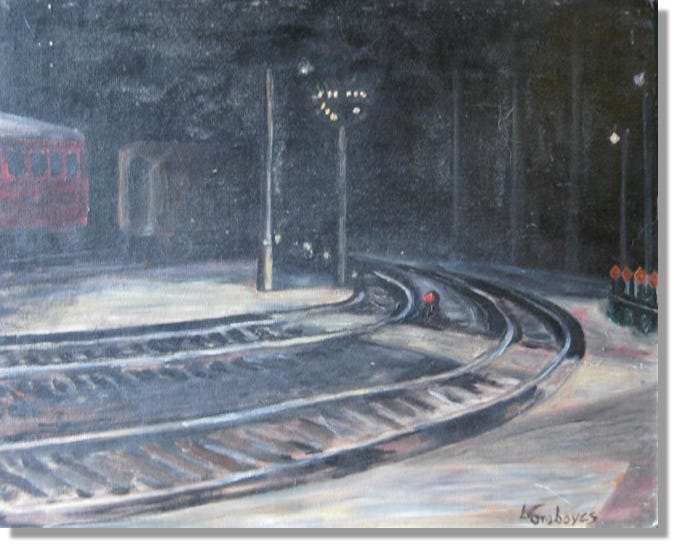

From age 80 to age 91, my mother served as an historical tour guide for the Civil War battlefields and museums of Petersburg, Virginia. As I recently wrote, one of her cherished experiences occurred in 2011, when she provided historical information to screenwriter Tony Kushner, who was in town working with Steven Spielberg on the filming of Lincoln. Much of Spielberg’s masterpiece was filmed around an old railway station which my mother had painted half a century earlier.

Petersburg, Virginia train station, painted by Lois Graboyes (c.1960).

Mom’s service as a Civil War tour guide was more than appropriate. As a young woman, she would have known people who were present at the scenes Spielberg portrayed in his film. The older townsfolk of her youth included former slaveholders and former slaves. Her birth certificate bears the signature (probably rubber-stamped) of Walter Ashby Plecker, Director of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics and, effectively, the state’s chief eugenicist. A medical doctor, he spent decades accumulating (and sometimes fabricating) genealogies of Virginians to systematically strip African Americans, Native Americans, and others of rights and privileges. Born 10 days before the attack on Fort Sumter, Plecker boasted in 1943 of his racial database on Virginians: "Hitler's genealogical study of the Jews is [probably] not more complete."

When she died in 2016 at 93, Mom was still living independently. When I visited her a month earlier, her legs were a bit wobbly, but her mind was still razor-sharp—the Jazz Age still alive and well in her thoughts. For hours, we discussed art, music, architecture, science, health, food, computers, religion, politics, history, and more. Two weeks or so later, during my next visit, she was drifting in and out of a mental fog, with reality melding with hallucination. She was acutely aware that something was badly amiss. She was confused and could barely sustain a conversation.

Rather than forcing her to talk, I began playing the piano—“Yesterday,” by the Beatles. My parents were not keen on the Beatles in the early days of the group’s fame, but they both immediately loved “Yesterday.” I thought that memory might comfort her. She asked, “Is that a Gershwin song?” I gently reminded her that it was a Beatles tune, and she said, in a whisper, “Of course it is.” She never liked making errors of any kind, and she had an encyclopedic knowledge of the Gershwins, whom she had revered for 80+ years. When she made that unimaginable error, it instantly struck me that her days were near their end, and I think she had the same thought. A talented amateur pianist, the day before her 92nd birthday, she had given a performance before a sizable audience. This brief snippet from that day shows her playing the Gershwins’ “The Man I Love” (1924).

To those children born today, September 14, 2022, may your lives be as long and well-lived as my mother’s. And here’s hoping that on September 14, 2122, your progeny are looking back with wonder on the eons that have passed since your birth and marvel at the innovations that time and ingenuity have wrought in the century since you took your first breath.

Listening to your mom play was such a treat. Your writing enjoyable as my memories of Tots and Teens came back to me. Petersburg was a wonderful place.

That is wonderful, especially the video of your mom. I have a somewhat similar video of my mother-in-law playing the piano a few months before she died. Thank you.