On the Mortality of New Yorkers, Presidents, Dogs, and TV Characters

Plus, the finest tribute ever written to a dog

DEATH AND LIFE IN GREAT AMERICAN CITIES

[A recent Bastiat’s Window essay, “The Minds of Economists,” featured anecdotes about four of my economics professors at Columbia University—illustrations of how we economists think the thoughts we think. I’m adding a fifth anecdote to that post, and here’s the text of that addition.]

At Columbia, I studied the economics of antitrust under Professor Donald Dewey—an amiable, loquacious storyteller with a fine analytical mind that often led in unusual directions. On one occasion, Dewey chatted with me and one other grad student about crime—which sometimes included murder—in the vicinity of the university.

I believe we were discussing Morningside Park—a magnificent 30-acre cliffside expanse designed in the 19th century by the great Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. For five years, I lived 500 feet from the park, not once setting foot within its bounds because of stern warnings by police and others. In the course of our discussion, the other student shook her head and asked Dewey:

“In the 1940s or 50s, you could sleep all night on a bench in the middle of Central Park without worrying about anyone bothering you. Now, it’s constant fear wherever we go. What went wrong with New York City?”

Without missing a beat, Dewey answered:

“You’re asking the wrong question. For most of New York City’s history, the streets were extremely dangerous. Back in colonial times, the murder rate was horrific, and this situation continued until the early 20th century. Then, for some reason, from maybe the 1920s till the late 1960s, the city became remarkably safe. What we’re experiencing now is simply a return to what New York had always known over the centuries. Rather than asking what went wrong since then, you should be asking what went right during that brief exception to the city’s long, violent history.”

DEATH AND THE IMPORTANCE OF VICE PRESIDENTS

The Boston Globe’s estimable Jeff Jacoby just posted a piece on the first president to die in office, and—in an election year that will likely pit an 82-year-old against a 78-year old, it reminded me of the extreme importance of who occupies the vice presidency. Jeff’s piece began with:

“Two presidential candidates face off in a rematch. One candidate, his affluent background notwithstanding, is seen as a populist; his supporters hail him as the champion of ordinary people and deride the incumbent as a pampered creature of the establishment. He's also the oldest person ever to run for president, and even his backers worry that he is not up to the demands of the job. All the while, the nation's problems are growing more serious. But the electorate is so polarized that all the two parties seem to agree on is how much they detest each other. … Welcome to the campaign of 1840.”

Fears about Harrison’s health, strength, and longevity proved terribly prescient, as he died exactly one month after taking office. His VP, John Tyler was a former Democrat whom the Whigs selected for reasons that are not entirely clear. Tyler’s one clear accomplishment in four years was establishing that a VP who rises to the presidency is actually president, and not some lesser seat-warmer; otherwise, he appears to have been a poor choice who landed the office because no one much cared who was VP.

Eight more times, death and resignation of presidents have handed the office to VPs. Two presidents who might have done much to ease racial and sectional discord—Abraham Lincoln and James Garfield—were assassinated. Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, exacerbated racial and sectional discord, and Garfield’s successor, Chester Arthur, focused on other things. Two decades later, William McKinley’s assassination removed a cautious conservative from office and replaced him with Theodore Roosevelt—a wide-eyed Progressive who favored a greatly expanded role for government and paved the way for the most destructive president in U.S. history—Woodrow Wilson, who held seething contempt for both African Americans and the U.S. Constitution. The Harding-to-Coolidge and Roosevelt-to-Truman successions offered no great ideological shifts. John Kennedy would likely have been more cautious and restrained in expanding the federal government than the power-drenched Lyndon Johnson proved to be. No mortality was involved in the shift from Richard Nixon to Gerald Ford—but the latter was chosen specifically because Nixon’s days were numbered and both parties viewed Gerald Ford as an acceptable soon-to-be president.

With the 2024 election shaping up as a rematch of two elderly candidates, Americans would do well to look closely at the vice presidential nominees of both parties.

I can’t mention William Henry Harrison and John Tyler without noting two bits of trivia. First, Tyler lived from 1790 to 1862, but one of his grandsons, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, is still living today, in 2024, 234 years after his grandfather’s birth. Second, a year or two ago, I noticed that Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was born on March 8, 1841 and immediately thought, “Holy Hell! He was born while William Henry Harrison was president. How many other famous Americans can make that claim?” So far as I can tell he is the only significant American figure born during Harrison’s one-month term.

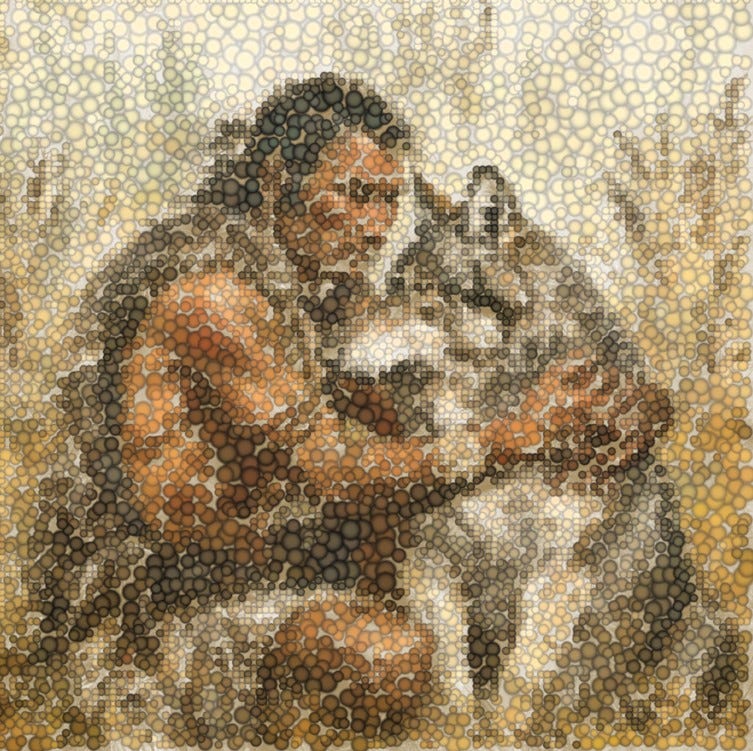

FOR THE LOVE OF DOGS AND CILANTRO

Dogs and cilantro have something important in common. Some percentage of humanity—10%, perhaps—has a genetic variation that causes cilantro to taste like soap to them. Such people not only dislike cilantro but are genetically incapable of even comprehending why cilantro-lovers are so enchanted by the herb. Likewise, some percentage of humankind looks upon dog-lovers with a similar mystification. My apologies to any readers of such inclination, as I will use this space to wax rhapsodic about the noble canine.

The topic arises because a dear friend and her father just lost their tiny 15-year-old dog. Their loss is all the more poignant because the dog was the special love of my friend’s mother, who passed away a few years back. So, in a strange sense, losing the dog is almost a second loss of the much-mourned mother and wife. As all but the dog-averse portion of mankind can easily comprehend, the grief that bereaved dog-lovers feel is as hollowing and desolating as anything we feel at the loss of a human companion—if not worse. I am no geneticist, but I suspect my love of dogs is as hard-wired into my brain as a cilantro-hater’s is into his or hers. Something in the dog’s nature, I believe, activates the same neurons that demand that we preserve and protect our own children.

Grief for elderly friends and relatives is different from the anguish one feels at the loss of a child. At a funeral I attended long ago—my father’s, perhaps—the officiating rabbi said this was a case of what Jewish tradition refers to as “an appropriate death.” A natural, expected departure at the end of a long, good life. The death of a child can never feel appropriate. As is true of other mammals and birds, parents have an in-born, desperate urge to shepherd their offspring from helpless infancy to adulthood—out of a primordial urge to pass our own genes along to infinite posterity. No matter what the circumstances of a child’s death, parents live beneath a pall of grief for the remainder of their lives. Why this is the case has somewhat mystified evolutionary biologists, who ask why evolution would want us to carry a debilitating burden when it cannot undo its cause. The best guess I’ve heard relates to our unique perspective as social, educable beings. Seeing the misery of bereaved parents around us is a constant and horrifying reminder to care for our own children.

My guess is that something about dogs tricks our subconscious souls into believing that they are our children. They come to us as helpless infants, and we feed them, care for them when they are ill, watch them grow, teach them, scold them, and do whatever we can to keep them safe—actions that differ very little from how we raise our children. Unique among animals, they seemingly exhibit the same emotions toward us that young children exhibit. And yet, while we expect our children to outlive us, the dog’s biological clock is painfully short. They grow old and depart from us in the briefest number of years. Logic tells us that these are merely animals, not children. But something in our genes will have none of that talk. To those genes, which drive our rawest emotions, these are our children. And the joy of their lives and the agony of their deaths never leaves us.

This is an ancient and sacred relationship. Properly speaking, these creatures aren’t mere dogs. They are Canis Lupus Familiaris—Household Wolves. Our partnership—this profound symbiosis—dates back at least 15,000 years. Apparently, love of the friendlier sort of wolves increased its owners’ chances of survival and procreation. And likewise, a fondness for the friendlier sort of humans increased the wolves’ chances of survival and procreation. Put those facts into the genetic oven and bake them for fifteen millennia delivers us to today’s emotional partnership.

Condolences to our dear friend and her father, and sweet memories of the life they nurtured.

A CLOUDY GLIMPSE INTO THE FUTURE

In an early 2000s TV serial we watched recently, one episode featured a flash-forward to the year 2085, where a prominent character was dying quietly in her bed at age 102, in cheerful surroundings, with a satisfied smile on her face and a thick layer of cataracts covering both eyes. After watching the scene, a friend was bothered by the eyes and asked me:

“[She] is a visual artist, so why wouldn’t she have cataract surgery of the kind that would clearly be available to anyone else who lived into the late 21st Century?”

My friend’s politics are considerably to the left of my own, and the following was my response (edited slightly for clarity):

”Here’s why she still had cataracts: Congress had rushed to pass Medicare for All in 2041—specifically so that President Bernie Sanders could sign the bill on his 100th birthday. She was approved for cataract surgery in 2063 but, given Berniecare’s high demand for services, chronic provider shortages, and rigorous review processes, the first available appointment for surgery was in April 2074. However, at the last minute, the surgeon had to cancel the operation to attend mandatory Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) re-education training, so the surgery had to be rescheduled for September 2089. (Incidentally, by 2041, Americans could barely remember that their country had once been willing to elect presidents as young and vigorous as Joe Biden, Donald Trump, and Harvey Weinstein.)”

LAGNIAPPE

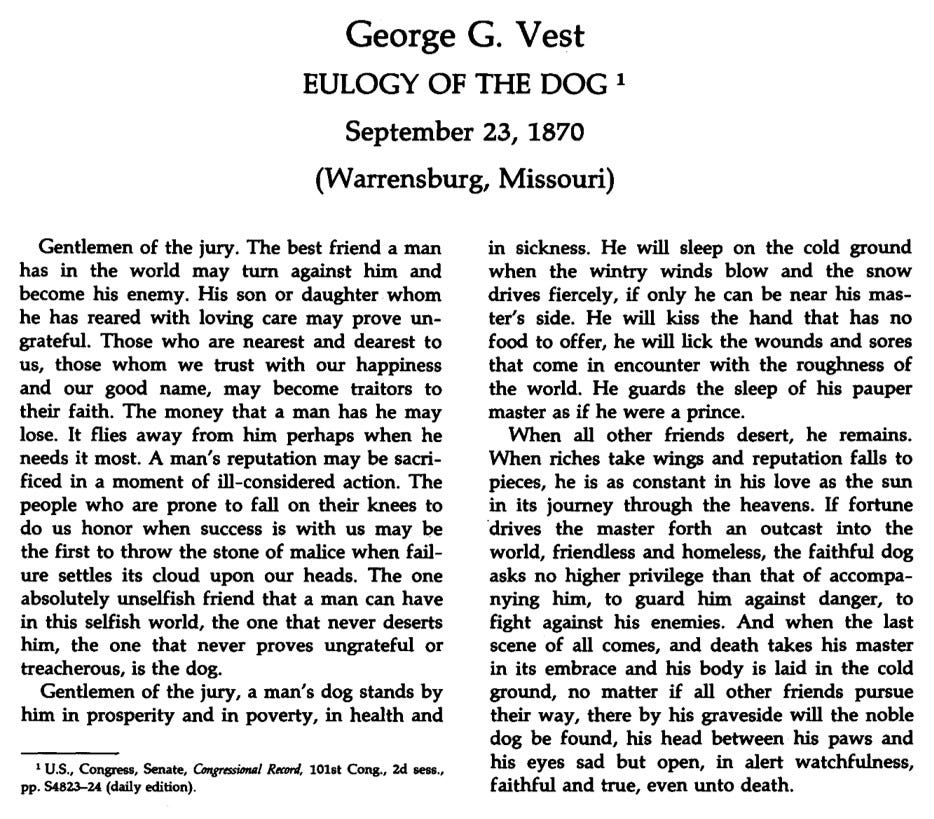

“EULOGY OF THE DOG”

One of history’s most celebrated statements of the mystical bonds between human and dog was a courtroom eulogy given by attorney George G. Vest for “Old Drum,” a hunting dog shot to death by a neighbor who suspected the dog of menacing his livestock. From Wikipedia:

“Vest took the case tried on September 23, 1870, in which he represented a client whose hunting dog, a foxhound named Drum (or Old Drum), had been killed by a sheep farmer, Leonidas Hornsby. The farmer (Burden's brother-in-law) had previously announced his intentions to kill any dog found on his property; the dog's owner was suing for damages in the amount of $150 (equivalent to $3,471 in 2022), the maximum allowed by law. … During the trial, Vest stated that he would "win the case or apologize to every dog in Missouri.”

In the end, the court required Hornsby to pay $50 (equivalent to around $1,200 in 2024). Vest later became a United States Senator and, a few decades ago, his eulogy was entered into the Senate record. I admit that I cannot read this eulogy aloud without breaking apart emotionally.

"...for some reason, from maybe the 1920s till the late 1960s, the city became remarkably safe."

Probably entirely coincidental, but that same period also encompasses what I call "The Great Pause."

In 1924, Congress passed the first-ever comprehensive immigration act. This turned off the spigot on mass immigration to the United States, and remained in effect until it was overturned by the 1965 immigration act.

As a result, a 40-year period of immigrant inculturation allowed things to settle down. This was of course very much aided and abetted by John Dewey and others in their work establishing the public school system in urban areas, with the explicit purpose of transforming immigrants into Americans.

As I say...this may just be coincidence. But honestly, it was the first thing that came to mind when I read your essay.

My brother has ALWAYS had dogs. We all loved our dogs, but even as a child the family dogs were in essence his. In the past 3 years he has lost two border collies, unexpectedly, about a year apart in early February. He was 74 when the second one passed, and I was seriously afraid it was going to kill him. We live 5 hours apart, so I spent hours online and on the phone, just talking about nothing in particular. This year, a year later, he is a little better. But he has one remaining dog, a three-legged pound adoptee with a beautiful personality, and she's getting on 14-15 years old.

I honestly don't know if he will be able to take another dog dying. Over the years he has 'lost', of course, several dogs, but he's been divorced for a while and the dogs have been his household family. He has children and grandchildren he loves dearly, but they don't live with him.

I've tried to get him to adopt a 'new' dog, but he says he can't, any more. The bond is truly deep.

And I think dogs probably come to be like their master, since every one of his has been a very good boy or girl, indeed. Every single one.