One Veep, Two Prez?

On a historian/pundit musing over one vice president serving under two presidents

Political pundit and historian Victor Davis Hanson wrote on February 9 about buzz over a potential 2028 presidential primary battle between Vice President J. D. Vance and Secretary of State Marco Rubio. In it, he posed a historical question whose answer he didn’t know. I could have answered his query on the spot because for some ungodly reason, I’ve accumulated a semi-encyclopedic knowledge about one of earth’s least compelling topics—the history of U.S. vice presidents and vice presidential candidates. [NB: This essay focuses ONLY on historical trivia, and not on the relative merits of Vance, Rubio, other potential candidates (of either party), or Hanson’s political conjectures.]

WOULD TRUMP-VANCE TO RUBIO-VANCE BE UNPRECENDENTED?

No. Not at all.

Hanson wondered aloud whether a Rubio-Vance or Vance-Rubio ticket might arise. He perceives some “subtext” in Trump’s praise for both men and (by my reading) also imagines that the president would favor Vance-Rubio because one vice president serving two successive presidents would be novel and odd:

HANSON: “I’ll have to look at my history, but I don’t know of a case offhand where a sitting vice president, under one president, has come back to have another term under another president. So, when Trump says, as vice president, yeah, we’ve got two great people, Vance and Rubio. He never says it, but the subtext is that Vance would be the top of the ticket and Rubio would be the bottom.”

Contrary to the putative “subtext” that Mr. Hanson divines in President Trump’s words, I have profound doubts that President Trump has pored intensely over the minutiae of vice-presidential history and agonized over whether a Rubio-Vance ticket would violate historical norms. But for anyone else pondering this question, such a ticket would not be unprecedented. Two U.S. vice presidents did, indeed, serve under two successive presidents apiece. In addition, two other ex-veeps were nominated to serve under second presidents, but the later tickets were defeated in the November polls. And in the most bizarre case, one former vice president considered a return to the vice presidency after having served as president.

2 VICE PRESIDENTS, 4 PRESIDENTS

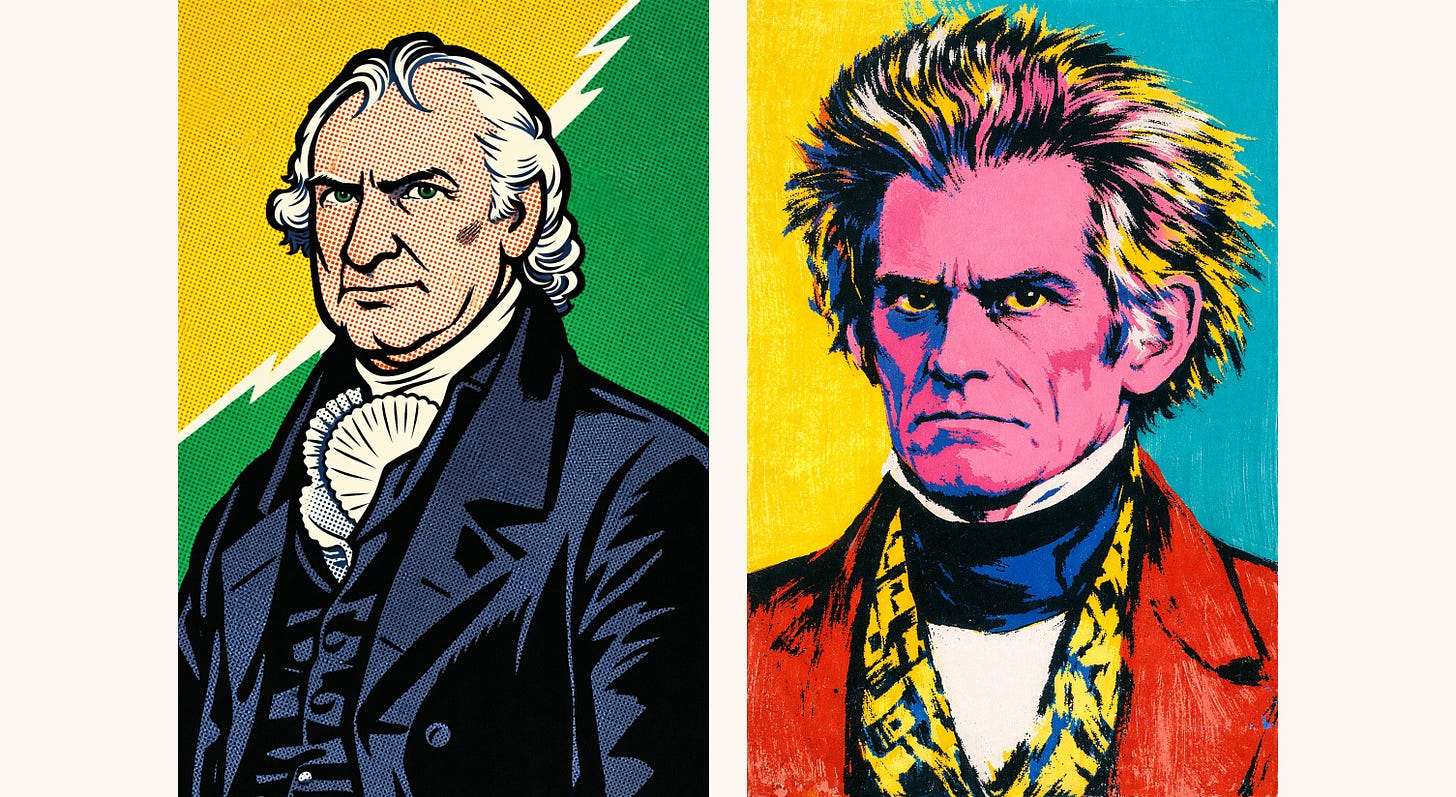

GEORGE CLINTON and JOHN C. CALHOUN both served as vice president under two successive presidents.

GEORGE CLINTON was elected vice president in 1804 after Thomas Jefferson dumped his first-term vice president, Aaron Burr. Clinton sought the presidential nomination in 1808, but lost to James Madison. The Democratic-Republican Party renominated him for VP, and he served under Madison until 1812, when he became the first VP to die in office.

JOHN C. CALHOUN was elected VP in 1824 and served under John Quincy Adams. Then, he was re-elected VP, serving under Andrew Jackson, who defeated Adams in 1828. In 1832, Calhoun became the first VP to resign the office—to take a seat in the U.S. Senate. At the time, Democrats and the American electorate had already voted to re-elect Andrew Jackson, and also to replace Calhoun as VP with Martin van Buren.

I portrayed Calhoun in the style of Andy Warhol because Calhoun’s hair and clothing remind me of Warhol’s contemporary, Rod Stewart. I portrayed Clinton in the style of Roy Liechtenstein because, well, why not?

2 VEEPS, 2 PRESIDENTS, 2 FAILED PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES

ADLAI STEVENSON I and CHARLES W. FAIRBANKS each served as vice president and were later nominated as running mates for presidential candidates who never became president:

ADLAI E. STEVENSON I was elected vice president in 1892 and served throughout Grover Cleveland’s second term. In 1900, Democrats nominated Stevenson to be running mate for William Jennings Bryan. The two were soundly defeated by William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt.

CHARLES W. FAIRBANKS was elected vice president under Theodore Roosevelt in 1904. He sought the presidential nomination in 1916 but was chosen, instead, to run for vice president again, this time under Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes. The two lost in a squeaker to Woodrow Wilson and Thomas Riley Marshall (described below).

Stevenson is drawn to resemble Mutt, from Bud Fisher’s “Mutt and Jeff” comic strip—because he kind of looked like Mutt. Fairbanks is drawn as a Warner Brothers cartoon character because his photos make him look like someone who would have been personally acquainted with Yosemite Sam.

1 VICE PRESIDENT/PRESIDENT, 1 PRESIDENT

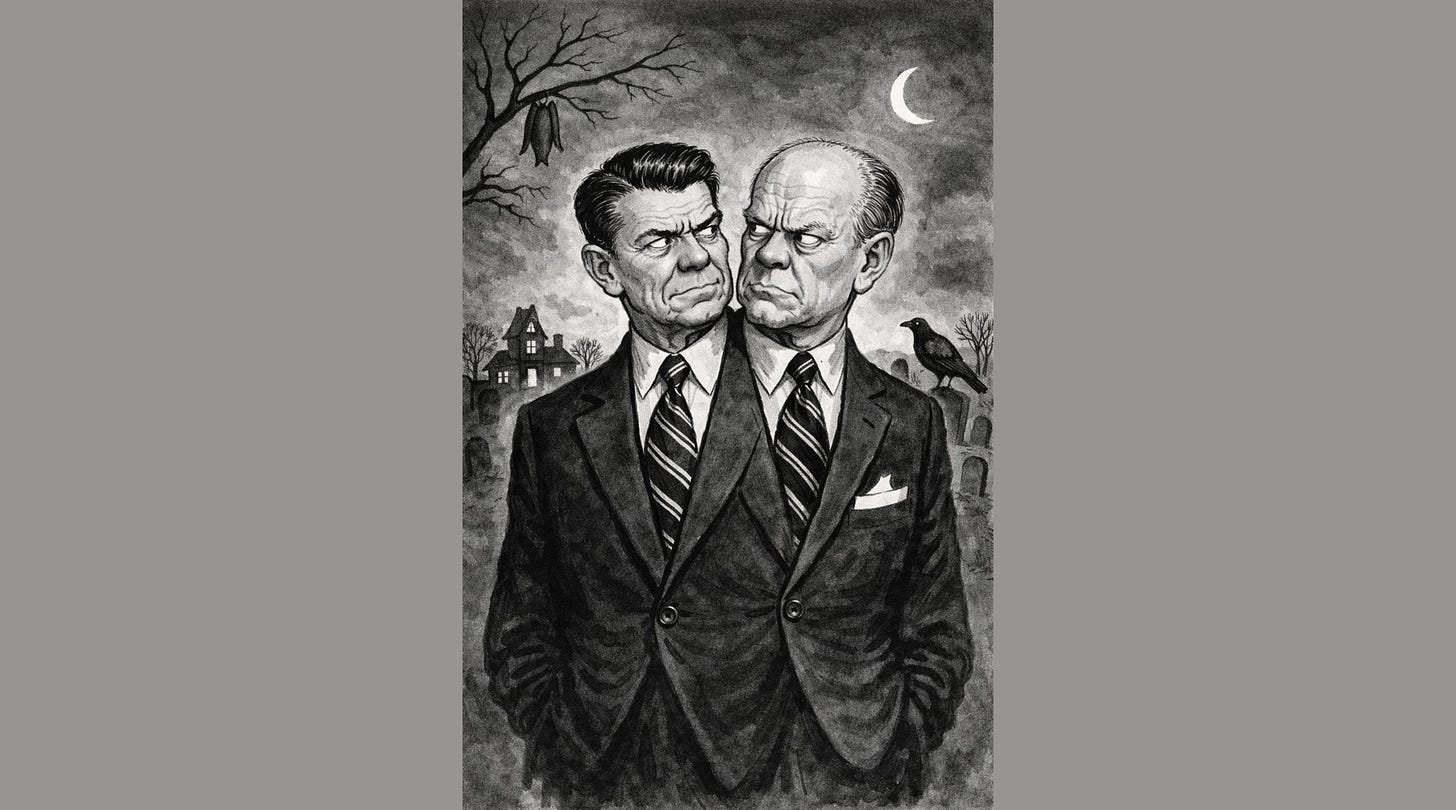

Here’s the oddest case of the lot. Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford briefly toyed with the idea of a “co-presidency,” but Reagan’s team came to fear the idea:

GERALD R. FORD was appointed vice president when the scandal-ridden Spiro Agnew resigned in 1973. Ford ascended to the presidency when Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in 1974. In 1976, the Republican primary campaign pitted Ford against Ronald Reagan, with Ford narrowly eking out a victory at the convention. In 1980, Reagan swept to the nomination, and his campaign floated the idea of recruiting Ford to return to the vice presidency under Reagan. Ford was amenable to the idea, but reportedly insisted on unprecedented powers for a vice president—effectively making Reagan and Ford “co-presidents.” Reagan balked at these demands, which some referred to as a “two-headed presidency,” and chose George H. W. Bush, instead.

Given that macabre notion of a two-headed president, I thought of representing them in the style of Charles Addams. ChatGPT did OK on the background, but I couldn’t get it to do the caricatures in Addams’ distinctive style and grew tired of trying.

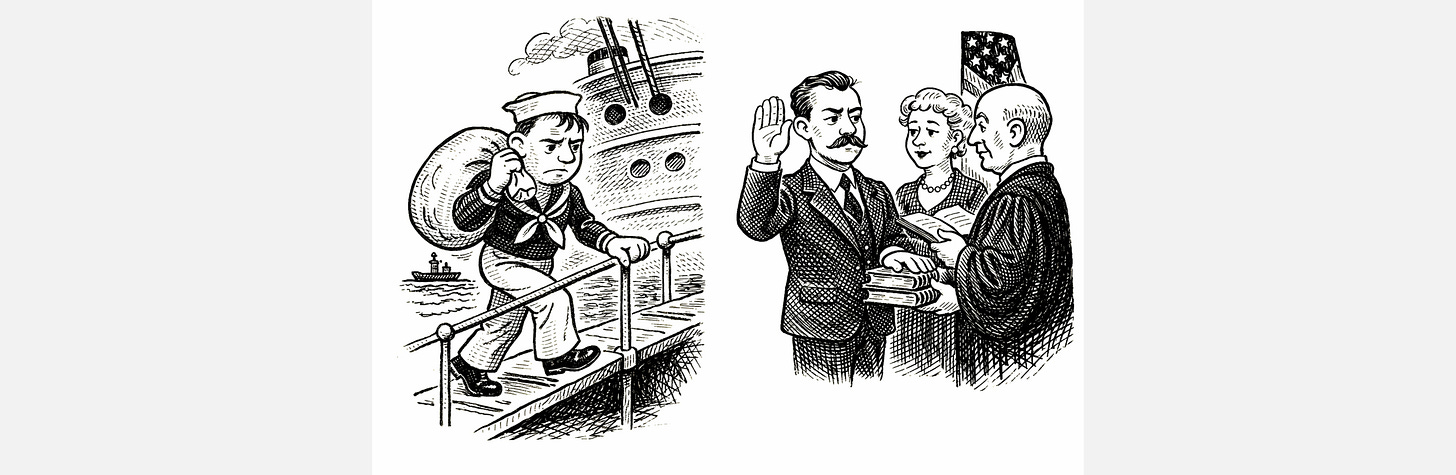

A SAILOR AND A VEEP

The office of vice president has long been an engine of humor, with jokes often coming from the veeps themselves. Here are some of the better-known examples:

JOHN ADAMS, the first vice president, called his office:

“the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived”

JOHN NANCE GARNER, FDR’s first vice president, is often quoted as saying that the vice presidency was:

“… not worth a bucket of warm spit.”

As noted in a recent Bastiat’s Window post, it’s likelier that he said it was:

“… not worth a bucket of warm piss.”

Garner also called the vice presidency:

“the spare tire on the automobile of government.”

THOMAS RILEY MARSHALL, Woodrow Wilson’s veep for eight years, liked to tell a story that:

“Once there were two brothers: One ran away to sea, the other was elected vice president—and nothing was ever heard from either of them again.”

Marshall would have known that aspect of the vice presidency well. In 1919, Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke, and for well over a year—through the end of his second term—First Lady Edith Wilson effectively assumed the powers of the presidency. She and Wilson’s advisors hid the president’s condition from Marshall to prevent him from triggering a succession crisis. Rather than telling him the news directly and officially, they had a newspaper reporter unofficially inform Marshall that Wilson appeared to be on the brink of death. With the lack of official notice from the White House, Marshall felt helpless to act on the news.

Marshall, by the way, was known for his wit. During a floor debate, one senator recited a long menu of America’s needs. Marshall’s response is still remembered today:

“What this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar.”

[ADDENDUM (2/14/26): Like VP Thomas Marshall, VP Adlai Stevenson I was kept in the dark about his president’s grave illness. During the Panic of 1893, Grover Cleveland had a couple of surgeries, including one in which a sizable chunk of his cancerous jaw was removed. Cleveland and his cronies didn’t wish to further spook markets, so the surgery was done in secret on a yacht in the Potomac. Stevenson disagreed with Cleveland on monetary silver, so the White House didn’t him to take the reins of power from the ailing Cleveland. They sent him across the country on some mission to get him out of DC.]

In 1976 Bob Dole was asked why he wanted to be Gerald Ford’s Vice President. He replied “inside job with no heavy lifting.” Which was poignant because Mr. Dole didn’t have use of his right arm due to his WWII injuries.

The context of the "good five cent cigar" quip finally shows the wit. It is often presented as an example of complacent elitism. Thanks!