Plato, China, Dixie, Disinformation

When governments, whether in contemporary China or in mid-century Virginia, decide to curate truth—to decide what citizens should and should not know

An earlier version of this piece ran at Inside Sources on May 24, 2022.

REALITY?

Long ago, my wife introduced me to Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” which explores the divergence of perception from reality. In 2022, my colleague Weifeng Zhong wrote about how Chinese propaganda distorted his youthful perceptions. I told him that, to a lesser extent, similar processes prevailed in my birthplace—Virginia under Jim Crow. When I wrote an earlier version of this essay back in 2022, social media platforms were busily censoring scientific and political debate, and the White House had established an Orwellian “Disinformation Governance Board” that lasted for four months (which is to say, four months too long).

In Plato’s allegory, Socrates describes people who have spent their lives chained within a cave, facing only a blank wall. Behind them, a fire burns. As people, animals and other objects pass by, prisoners see only shadows on the wall. Most assume the shadows are reality, but escapees (philosophers) discern otherwise, using logic to fathom the true nature of those objects. Others are content to know only the shadows.

MASSACRE?

In “Fleeting Freedom and Propaganda Lessons in Hong Kong,” Weifeng described his 2006 arrival at the University of Hong Kong — nine years after China reclaimed the former British colony and Weifeng’s first time outside of Mainland China:

“[M]uch of the city still felt foreign to someone like me who had never left mainland China. One of the first things I saw on campus was a bloody-red sculpture of piled-up dead bodies with disturbing facial expressions. Curious what that ‘eyesore’ was about, I read the inscription underneath: ‘The Tiananmen Massacre.’ I wondered, ‘What massacre is it talking about? Nobody died in the Tiananmen Square protests.’ Or so I was told growing up.”

For Weifeng, hundreds (thousands?) of slaughtered protesters didn’t exist. Hong Kong’s then-open society let him learn otherwise. (He noted that in 2021 the statue was removed amid Hong Kong’s fading openness.) Today, in America, Weifeng uses artificial intelligence to probe the shadows of Chinese propaganda—discerning truths about the country’s foreign policy, protester crackdowns and pandemic statistics.

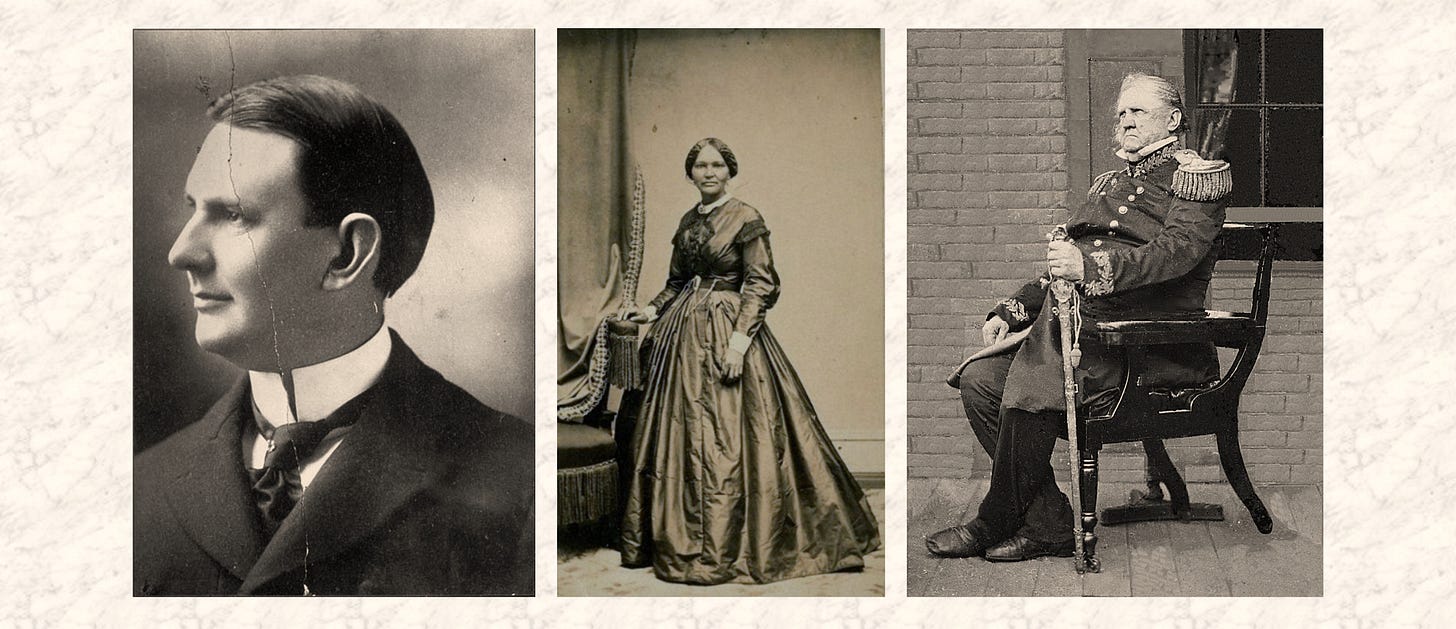

STERILIZATIONS? SEAMSTRESS? GENERAL?

Mid-century Virginia was governed by the fervently segregationist Byrd Machine. Driven from office in the 1960s, the machine’s fetid legacy persisted for decades.

In the late 1990s, my mother was around 75 years old, exceedingly intelligent and a lifelong history enthusiast in a state obsessed with history. I showed her a gut-wrenching documentary, “The Lynchburg Story,” about the 8,000-plus Virginians sexually sterilized by Virginia’s government from the 1920s through the 1970s—victims of an arrogant regime intent on perfecting the White race via the degenerate science of eugenics. (Dr. Albert Priddy, shown above, was a chief instigator.) Mom asked, somberly, “Why didn’t I ever hear about this before?”

The reason isn’t much different from why Weifeng never heard about the Tiananmen Massacre. In Virginia, as in China, the government committed unspeakably cruel acts and wasn’t anxious to share that history. Virginia was immeasurably more open than China, but even here, we often saw only shadows.

In 2011, at age 89, Mom had worked for a decade as a tour guide at the museums and Civil War battlefields of our town. Steven Spielberg was filming his magisterial Lincoln just a few steps from her office. Tony Kushner, the film’s screenwriter, visited the office a few times and asked Mom about the town’s history and architecture. When the movie came out, one prominent character was Mrs. Elizabeth Keckley, an African-American seamstress who was Mary Todd Lincoln’s personal dressmaker and confidante. Mrs. Keckley was born into slavery just outside our town. For a time, she lived a short stroll from the building my parents purchased a century later for their store. Echoing our earlier conversation, Mom wondered why she had never heard of Mrs. Keckley, given the town’s enthusiasm for Civil War history. “You know exactly why,” I said. She nodded.

Our school textbooks presented perverse views of antebellum life (e.g., “A feeling of strong affection existed between masters and slaves in a majority of Virginia homes.”). Half the town was deeply proud of its Confederate ancestors, and a local Lincoln confidante who purchased her way out of slavery was especially unlikely to enter our school lessons. Around age 4 or 5, I could recite the list of America’s then-34 presidents and then proceeded to learn their vice presidents and election opponents. But I only learned well into adulthood that Gen. Winfield Scott — “foremost American military figure between the Revolution and the Civil War,” 1852 presidential nominee and the Union Army’s first commanding general — was also born just outside our town.

In Virginia’s schools, as in China’s, the shadows on our chalkboards reflected the government’s preferred narrative and disdain for “disinformation.” In our own time, with calls to curate public discourse, George Santayana’s words resound:

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

THE TOMBSTONE HOUSE

In my hometown stands an odd anomaly—a 1920s house whose stone façade is composed of remnants of 2,200 Union soldiers’ gravestones. Some locals believed that the house is covered with actual gravestones, with the soldiers’ names turned inward, though this is almost certainly untrue. Most likely, the original stones, which stood upright, were cut in half below the inscriptions, with the inscribed portions lain horizontally, flush with the ground, to make mowing easier. The blank lower halves were then sold to a local family for construction purposes. I grew up with an encyclopedic knowledge of the town and passed the house a thousand times by car and by bike, but I never noticed it or heard of it till I was 55 or so. I asked my mother, then an historical tourguide and nearing 90, whether she knew of the house. She said yes, but added that the historical bureau didn’t seem keen to talk about it. More on the house at Atlas Obscura.

The same is true today in all sorts of important and not so important ways. I read something recently about an occurrence in a South Asian country. I mentioned it to my son who said that wasn’t exactly correct. He is in a position to know. When I was in college the administration building was taken over by students demanding the end of the Vietnam War. My Father send me the NYT article about the incident. They got a lot of facts wrong, but told a convincing story. Since then till today I realise that most of what you read in history books and the media isn’t always accurate. What they don’t even discuss is even more flagrant.

I'm idly curious whether "The Lynchburg Story" discusses how Virginia had the power to enact these repugnant policies? Do they discuss "Buck v. Bell," an infamous Supreme Court decision whose 8-1 majority holding was penned by that great light of "Progressivism," Oliver Wendell Holmes? Whose peroration is the horrifying declaration that "...three generations of imbeciles are enough"?

I hold no brief for Virginia's eugenics laws--which were later used by the Nazis as the model for the Nuremberg laws--but all that could have been ended had Holmes actually done his job--to provide "Equal Protection Under Law."