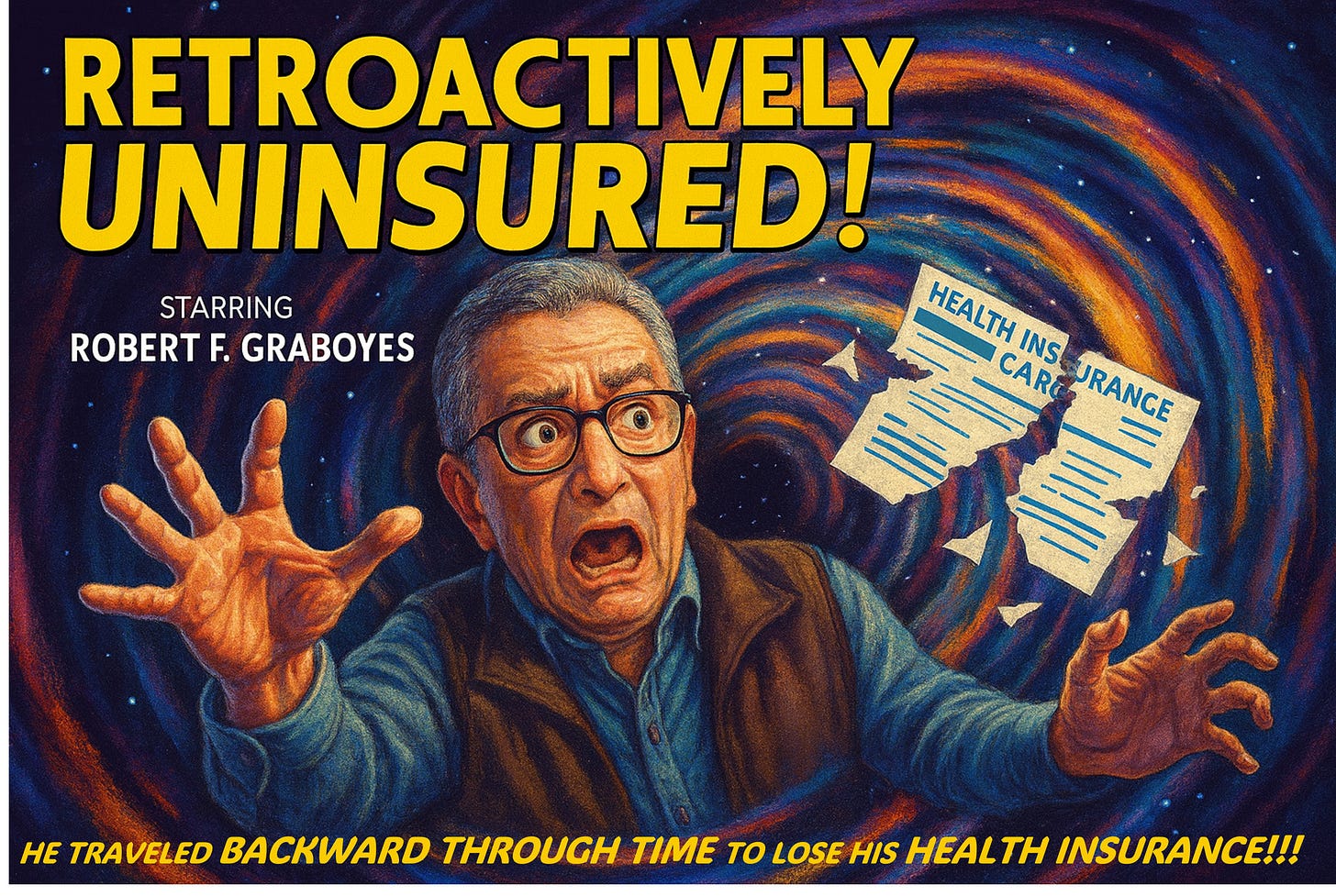

Retroactively Uninsured!

Sending condolences and canceling health insurance coverage in one brief letter

Thanks again to all the readers who sent condolences after my wife, Alanna, passed away and who offered assurances that they would patiently await the return of Bastiat’s Window. I’m back—rested and in great emotional and physical shape. The pause in my writing occurred not because of grief-induced writer’s block, but rather because I’ve been so busy handling the avalanche of financial and legal tasks that follow a death; donating clothes and art supplies; reconfiguring household possessions to fit my altered needs; visiting friends; cooking meals for guests; getting back into my exercise regimen; reading books; attending concerts; planning trips; and enjoying quiet meals, coffee, and walks along the Potomac. I’ve also been working on ways to boost Alanna’s posthumous reputation as an artist and to use that reputation to generate charitable donations. Building a new life is all part of my journey, and I’ll share further thoughts in future essays. Meanwhile …

In early-to-mid-July, a month after my wife’s death, I received a sordid missive informing me that my own health insurance had been canceled, retroactively to July 1. So, between dealing with seismic emotions, planning a memorial service, and handling the pyroclastic flow of paperwork that follows a loved one’s death, I had only a few days to figure out how to purchase a new health insurance policy and to jump through all the hoops necessary to accomplish the task in time to restore my coverage on August 1. To my knowledge, no mechanism existed enabling me to avoid a one-month lapse in comprehensive coverage.

Today’s essay asks which institutional circumstances led to this ordeal but offers no definitive answers. It’s a memo to myself—a reminder to explore this question in the coming months. It’s also a call for readers (especially those with intimate knowledge of insurance law) to suggest possible explanations and things I ought to explore.

Fear not—I experienced no health problems in July and, as of August 1, possess a shiny new policy. Had I needed care during the July interregnum, there would have been lesser, but adequate, coverage under Medicare Parts A and B. If push had come to shove, more complete coverage would likely have been possible through some soul-crushing process of filing for benefits under COBRA. Plus, there was always the option of heading to an emergency room and procuring a cornucopia of services under EMTALA. But I (a putative expert on health insurance) and a close advisor (who is high up in the regulatory world) had to slalom our way down a steep slope of questions as to what my rights and options were under current law. We couldn’t imagine what this process must be like for people without a heavy-duty background in the field.

Despite my decades of studying American health insurance, it’s impossible for me to establish who is really to blame. Candidates include the insurance company, insurance industry lobbyists, my late wife’s former employer (through whom I secured the policy), Congress (which wrote the Affordable Care Act and the Social Security provisions that govern Medicare), federal regulators (who implement the laws originating in Congress), the Virginia legislature (which wrote my state’s insurance laws), and state regulators (who implement those Virginia laws). In my mind, all of these people are seated in the parlor, eyeing one another suspiciously, and awaiting the arrival of some master detective like Hercule Poirot or Cordelia Cupp.

For background, the retroactively canceled policy was procured through my wife’s former employer, which provided her with post-retirement insurance and offered her spouse (me) a parallel policy when I left my previous job in 2022. When I purchased that policy, I specifically asked whether I would be on her policy and whether my policy was contingent upon her status. I was told that my policy was entirely separate from hers and not directly tied to her coverage—a time bomb of misinformation that exploded on me in July 2025.

The overriding question on my mind today is why some combination of public policy and market forces fails to assure continuity of coverage at traumatic moments, such as the loss of a spouse. A letter instructing me to procure a new insurance policy by, say, September 1 or October 1 would have been mildly irritating but easily manageable. Retroactive cancellation and a rapidly approaching deadline to secure coverage by August 1, on the other hand, added incredible stress at a time when I needed no additional worries.

In the end, I suffered no harm, and the purchase of a new policy went smoothly and quickly. But the question I plan to explore is how policies and institutions can come crashing down on Americans at vulnerable moments—and how such ordeals can be prevented.

TAKE OUT SOME INSURANCE ON ME, BABY

Tony Sheridan, backed by the Beatles (1961)

Your gift for imagery shines even in this tale of slogging through the bureaucracy. I'm glad it all worked out.

As a lawyer, this part stands out to me:

"I was told that my policy was entirely separate from hers and not directly tied to her coverage—a time bomb of misinformation that exploded on me in July 2025."

Whoever told you this is the villain, if the representation was contrary to the actual insurance policy.

Unfortunately, there is not likely much you could do about it. The contract most likely contains an "integration clause" providing that it is the complete agreement of the party; and, because the promise is contrary to the policy itself. Unless this promise is in the written contract, it is likely unenforceable -- though, if you lived in California like me, the courts might let you sue for fraud anyway. Generally, oral promises that are contrary to a written contract are unenforceable.

Insurance is especially frustrating because we never even seen the written insurance policy and it can be hard to even get the insurance company to give it to you -- additional arguments that might have had merit had you needed to file a lawsuit. Indeed, if you were never given a chance to read the contract before agreeing to it, you might even have a strong argument on this point.

As to who is to blame: Surely all of the above, but most especially the government takeover of both the health care and insurance markets, which make it almost impossible for the insurance companies to make money, and which only make things worse for consumers.