Sic Transit Gloria Mundi

Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make wildly popular.

An earlier version of this piece appeared a week after Bastiat’s Window opened for business in 2022—when there were almost no readers.

WHEN CREAM TURNS TO CHEESE

Whether in politics or entertainment or fashion or science or beauty, beware of being at the top of the mountain, for from there, the plummet is longest and most lethal. A metaphor for this notion lies in a song that has caused eyes to roll and skin to crawl for over half a century, despite its all-star cast of creators, a brief period of phenomenal popularity, and enormous influence over the music that followed.

Back in 2022, a fellow musician friend mentioned the song, “Theme from A Summer Place,” written for A Summer Place (1959)—a teen romance, set on the coast of Maine, featuring Sandra Dee and Troy Donahue. My friend referred to the song as “one of the sillier/cheesier tunes ever recorded.” I responded that for me the song, is something of a riddle and perhaps indicative of a larger phenomenon of our time—our habit of heaping scorn on that which we showered with praise just a short time ago.

To modern ears (mine included), “Theme from A Summer Place” is, indeed, dreadful. The song is the ultimate exemplar of “elevator music.” As such it has been used in countless films and television programs—usually to ironic effect. In Animal House (1978), it accompanies a drunken teenager fumbling with his even drunker date’s clothing. In Legend (2015), its syrupy sweetness precedes a brutal murder.

The song is as cheesy as can be, but I'm not sure whether it was intrinsically cheesy from the outset (as 1970s clothing was), or whether is was the victim of time, overuse, and endless imitation. The most famous version—the one used in the film—was performed by the Percy Faith Orchestra. Listen to its treacly, string-heavy sound, and in 2024 you may wonder how any studio ever thought it was worth releasing—or how Percy Faith became a name.

But for a time, Percy Faith was immensely successful. “Theme from A Summer Place” was the #1 hit single for 1959, as was his similarly styled “The Song from Moulin Rouge” (“Where Is Your Heart”) in 1953. His Wikipedia bio says:

“Faith remains the only artist to have the best selling single of the year during both the pop singer era (“Song from Moulin Rouge”) and the rock era (“Theme from A Summer Place"); and he is one of only three artists, along with Elvis Presley and The Beatles, to have the best selling single of the year twice.”

Another recording of the song became a smash hit for singer Andy Williams. He, too, had an anodyne sound that fell into self-caricature after a while.

But the song’s provenance was imposing. It was composed by Max Steiner—one of the greatest film composers of all time. He didn’t have a lot of misses in his career, which featured, among others, his classic scores for The Treasure of the Sierra Madre; Casablanca; Arsenic and Old Lace; Now, Voyager; Little Women; King Kong; The Searchers; and Gone with the Wind. Furthermore “Theme from A Summer Place” was not some late-career failure by an over-the-hill-composer. With this composition, Steiner knocked the ball out of the park—a #1 hit that became a national obsession. I would ascribe the song’s downfall to four factors:

[1] LETHAL SUCCESS

The song’s immense success was its own worst enemy. A Summer Place came out when I was 5 years old—the same year I began my music studies. The song blared constantly from our automobiles’ AM radios—enough so that it soon became a dreadfully annoying cliché. And very likely, Boomers’ weary distaste for the song—and, more generally, for the Percy Faith sound—has been subtly passed along to later generations.

[2] DEATH BY IMITATION

The song was endlessly imitated. The slow, undulating, stringy 6/4 rhythm formed the basis for countless second-rate romantic film scores, and the style soon became intolerably hackneyed.

[3] THE DAY THE MUZAK DIED

The song had the bad luck of emerging at the precise moment when Americans collectively grew sick to death of “elevator music.” “Theme from A Summer Place” bore some resemblance to the audible schmaltz that once permeated shopping malls, office lobbies, voicemail systems, and—of course—elevators. Today, one might wonder why businesses surrounded customers with irritating sounds. The surprising answer is that elevator music, much of it produced by the Muzak Corporation, was relatively well-liked by the public until just around the time that A Summer Place hit the theaters in 1959. But by around 1960, Muzak’s omnipresence had begun to grate on the public. The 1969 film, Goodbye, Columbus (based on Philip Roth’s 1959 eponymous novella), features a running joke on elevator music; Ron Patimkin, a dull ex-college athlete, repeatedly describes the pride he holds for his collection of records by Mantovani and Kostelanetz—two famous purveyors of elevator-style music.

When I thought of the title for this section, I did a Google search and found, as expected, that others already had the idea. A 2009 Wall Street Journal piece (“The Day the Muzak Died: Remembering a Soundtrack to Life”) mentions A Summer Place, the Beatles, and Percy Faith. A BBC program (“The Day the Muzak Died”) offered a quite entertaining “part love letter, part obituary to the music of Muzak Corporation.”

[4] SUBLIMINAL REDUCTION

The song evokes 1950s/1960s childhood memories that transitioned from fond to annoying.

I’m a bit of a musical sleuth, and I strongly suspect that Max Steiner based the melody on two tunes that subliminally reminded viewers of every white, middle-class family or neighborhood get-together of the period. Allow me to stereotype a wee bit. At each such event, pre-teens and teens would self-isolate in a basement. At some point, a musically talentless boy would open the dusty piano and perform “Chopsticks.” Then, two giddy and equally talentless girls would sit together on the bench and bang out a duet of “Heart and Soul.” Afterward, an awkward boy with even less musical capacity would nervously round out the repertoire with “Peter, Peter, Pumpkin Eater” and “The Knuckle Song.” Then, other kids would repeat that four-song Playlist-from-Hell over and over. (I have no idea whether any of these songs are still played.)

After writing the earlier version of this essay, it occurred to me that “Theme from A Summer Place” combines the 6/4 rhythm of “Chopsticks” with the C-Am-F-G chord pattern of “Heart and Soul.” In 1959, both songs were emblematic of youthful 1950s innocence, and A Summer Place was a drama on the loss of that innocence. I’m guessing that the resemblance to those ditties was no accident—that the master composer Steiner knew exactly how to pluck the desired emotions and memories from the listener’s subconscious.

Assuming my theory is correct, Steiner was quickly copied. “Chopsticks.” reconfigured for 4/4 time, lurks beneath the opening of the theme song to television’s My Three Sons, which premiered the year after A Summer Place. While I have involuntarily hummed that TV song as an earworm for half a century, I never noticed till 2022 that its dominant saxophone melody is a countermelody to “Chopsticks.” “My Three Sons” composer Frank de Vol clearly used the song to evoke teenage innocence—as I suspect Steiner did.

For many people, the endless rounds of “Chopsticks” and “Heart and Soul” at teen gatherings became tedious and irritating. (I was always a musical snob, so they irritated me from the start.)

[Curious aside: “Chopsticks” was originally titled, “The Celebrated Chop Waltz,” and was written in 1877 by “Arthur de Lulli”—a pseudonym for 16-year-old Euphemia Allen, whose brother, Mozart Allan, was a music publisher. It was so named because one was supposed to play it with the hands configured vertically, like meat cleavers, chopping away at the keyboard.]

O, CRUEL HINDSIGHT

I don’t disagree with my friend’s contention that “Theme from A Summer Place” sounds silly and cheesy, I’m just not sure it was when it came out, or whether, instead, it was retrofitted with those unfortunate qualities. And therein lies a bit of deeper significance. We live in an era that is quick to vilify the aesthetics of the past, be it the writings of Mark Twain; the humor of Mel Brooks, Woody Allen, and Jerry Seinfeld; or the statuary of Theodore Roosevelt. Though you won’t find me listening to “Theme from A Summer Place” (except when writing this piece), I’m willing to bear a measure of respect for something that, though alien to modern sensibilities, was clearly at home in its own time.

From 1409 to 1963, each papal coronation featured a procession that was halted three times. At each stop, a master of ceremonies would fall to his knees before the Pope and proclaim, mournfully, “Pater Sancte, sic transit gloria mundi!” (“Holy Father, so passes worldly glory!”)—a triple-reminder to the new Pontiff that earthly glory is temporary.

A measure of peaceful humility comes from recognizing that our views of the past are distorted and a realization that, in fair turnabout, future generations will gag at whatever appeals to us today.

RAPID ONSET OBSOLESCENCE

The above video, from the 1967 film, Bedazzled, offers a splendid take on the brutality of passing fancies. In the film, Stanley Moon (Dudley Moore) is a loser who sells his soul to Lucifer (Peter Cook) in exchange for seven wishes that he might use to win the heart of his coworker, Margaret Spencer (Eleanor Bron), who barely notices that he exists. Lucifer (who calls himself George Spiggott), frustrates each wish by perverting its meaning.

Here, Stanley wishes to be a rock music sensation, with Margaret as a starstruck fan. He gets his wish, with Margaret in the audience, apoplectic over the sight and sound of Stanley. But, just as Stanley finishes his song, Lucifer/Spiggott follows him onstage, singing in a radically different style. The audience, including Margaret, instantly loses interest in Stanley’s loud, emotional, glittery style and is mesmerized by Lucifer/Spiggott’s cool, contemptuous, psychadelic droning. Kind of like the Beatles shoving Elvis aside.

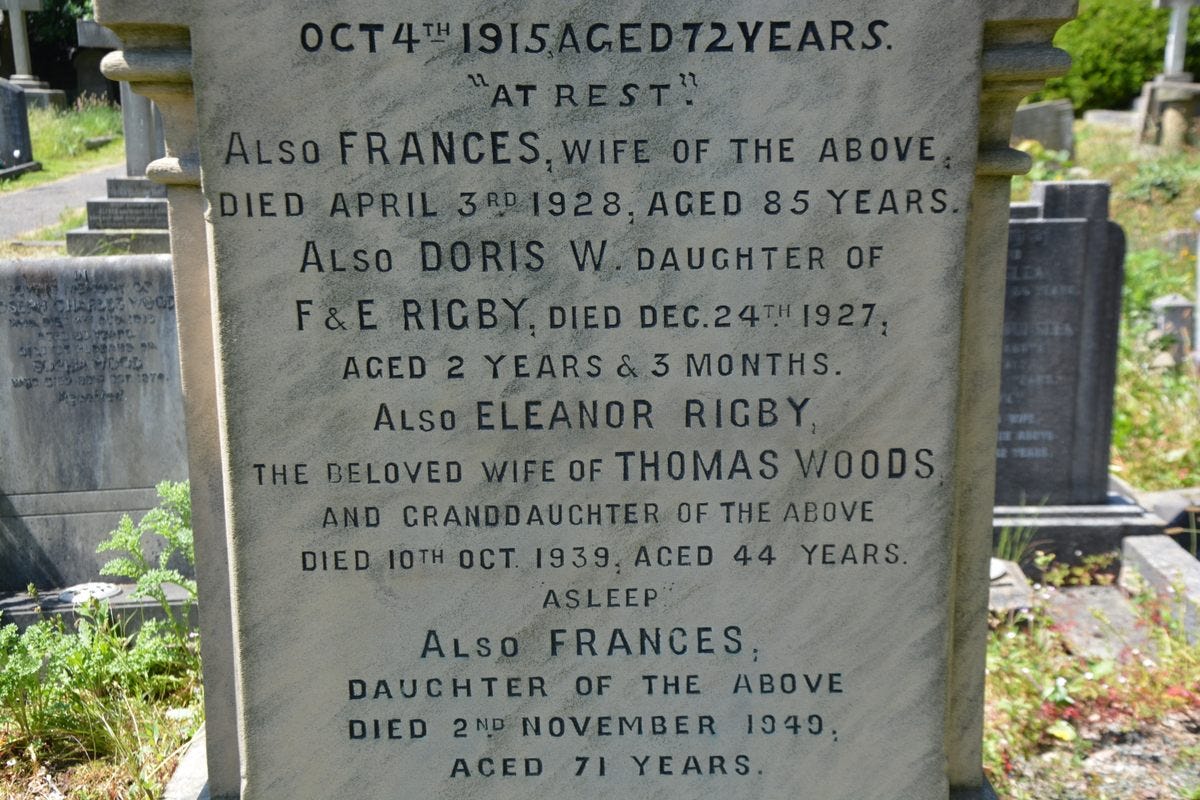

Speaking of which, Eleanor Bron was close to the Beatles, and her name partially inspired McCartney’s masterpiece, “Eleanor Rigby.” According to the Atlas Obscura website:

“McCartney attributed the name to a combination of the actress Eleanor Bron, and the name of a store in Bristol, “Rigby & Evens Ltd, Wine & Spirit Shippers.” He also later admitted he might have unconsciously borrowed her name from [a gravestone at St. Peter's Church in Liverpool].

John Lennon and Paul McCartney first met on July 6, 1957 at a social at St. Peter’s, where Lennon was performing as part of The Quarrymen. In the years before they were The Beatles, the two regularly took shortcuts through the graveyard. Perhaps McCartney had unconsciously absorbed the fact that for an actual Eleanor Rigby, earthly gloria transited when she was a mere 44 years old.

Part of the reason A SUMMER PLACE seems awkward is that it was originally written as part of a film score, i.e. a supporting action to what was playing on the screen. Take the screen action away and the music has to stand on its own. That transition sinks a lot of scores, or illustrations to books or magazines. Not always; the Tenniel illustrations to Lewis Carroll's books have held on at least as well as the books. But often. It's an intrinsic peril when a creator is working as part of a group effort.

The youtube video of the orchestra with suits, ties and wingtip shoes was...well, it was.

But now that song is playing back in my head and it will be some time before I can turn it off... Of course now it has fast-forwarded to Travolta's Summer Sun. Can I ever escape?