SoHo + 45

Avant-Garde's Hot Center Revisited

BOB: In the 1960s and 1970s, New York’s SoHo evolved from a run-down industrial district to a world-renowned hive of avant-garde artists and musicians, living and working atop edgy restaurants and galleries. This transformation was stoked by (1) preservationism, (2) a memorable nickname, (3) Jane Jacobs’s assault on Robert Moses, (4) postwar economic winds, (5) rent control laws, (6) pragmatic tolerance of zoning violations, and (maybe) (7) covert CIA support for abstract expressionism as a Cold War strategy.

In January 1979, Vivian Raynor wrote in the New York Times:

“SoHo has lacked only a guidebook to confirm its status as a tourist attraction. The gap has now been filled by SoHo, an exhaustive survey by Helene Zucker Seeman and Alanna Siegfried.”

In 1980, NYC’s dysfunctional subways introduced me to Ms. Siegfried, and her book led indirectly to our 1985 marriage. Alanna studied art under leading abstract expressionists at Queens College and worked as a textile designer north of SoHo. She’s still an artist—still working on canvas and fabric.

Having married the most interesting person who ever crossed my path, I asked Alanna to work with me on two articles. This one, “SoHo + 45,” explores the genesis of SoHo. “Concrete Lessons from Abstract Expressionists,” coming soon, will share surprisingly practical lessons that Alanna learned from masters of a movement generally seen as in-the-clouds, not down-to-earth.

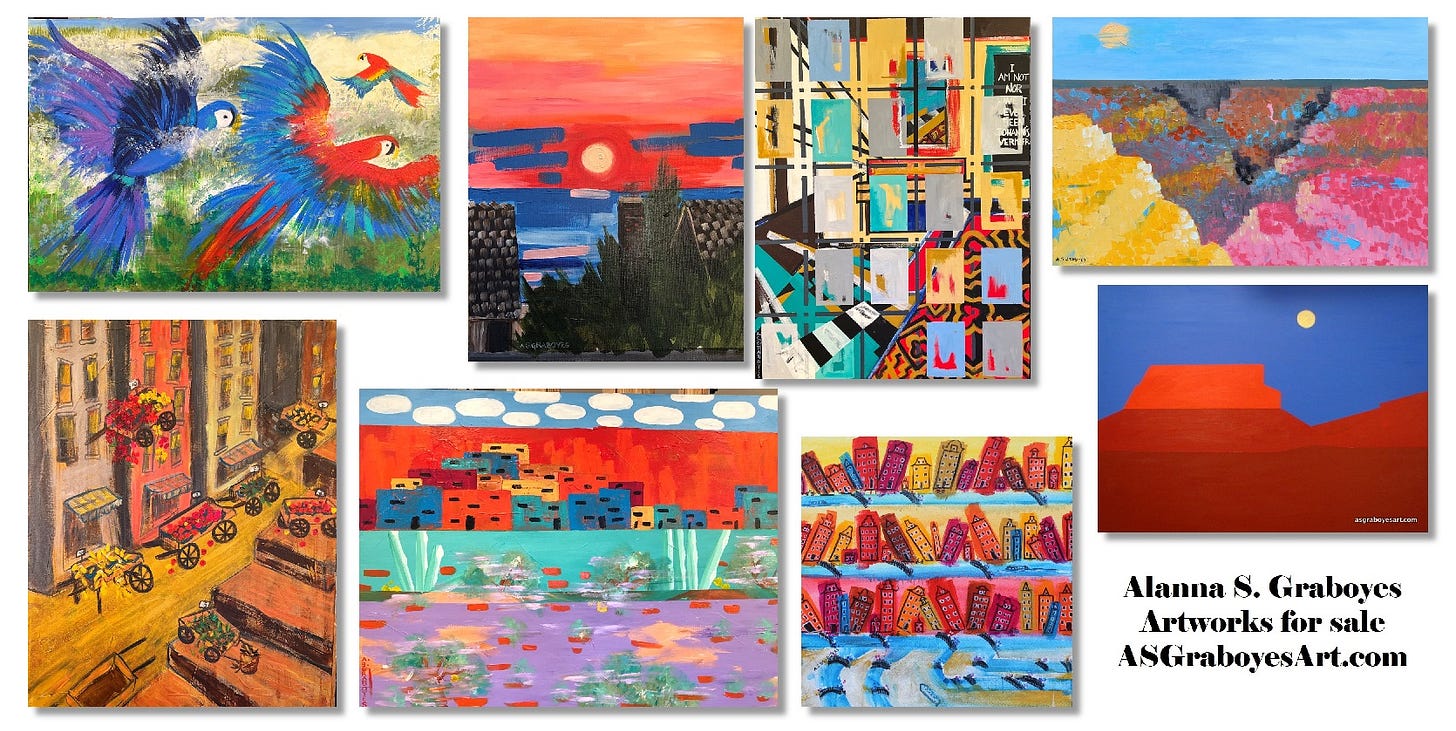

First, a brief advertisement. Here are two montages of Alanna’s current paintings on canvas and fabric. These and many others are for sale at ASGraboyesArt.com.

SoHo + 45: Avant-Garde's Hot Center Revisited

By Robert F. Graboyes and Alanna Siegfried Graboyes

SoHo, Genesis of a Marriage

BOB: On a bright autumn morning in 1980, Alanna Siegfried—a Natalie Wood doppelgänger—entered the café where I sat. She was visibly fuming over her commute, which had taken 2½ hours, thanks to a transit union semi-strike. I offered kind words, we dined together, and she mentioned having co-authored the first guidebook to SoHo. Maybe 10 days later, I bumped into her again and said, “I’ve been meaning to call.” Her face telegraphed a strong skepticism as to my sincerity till I said, “I read your book.” Our fate was sealed.

ALANNA: Bob’s yellow sweater and slight Southern accent also did the trick.

From Bronze Age to Iron Age

BOB: SoHo’s metallic history echoes that of Ancient Greece. In The Doomsday Myth: 10,000 Years of Economic Crises, Charles Maurice and Charles W. Smithson wrote:

“The ancient Greeks switched from bronze to iron because a resource shortage—a tin crisis—raised the price of bronze. They substituted a new product [iron] for the one that had become scarce. And once they gained experience with the new product, they found ways of reducing the cost of production. Hence, competition reduced its price. In this way, the Greeks moved out of the Bronze Age into the Age of Iron.”

In SoHo, Alanna and Helene Seeman wrote:

“An American architectural innovation, cast iron was cheaper to use for façades than materials such as stone or brick. … The buildings could be erected quickly—some were built in only four months' time. … Previously, bronze had been the metal most frequently used for architectural detail. Architects now found that the relatively inexpensive cast iron could form the most intricately designed patterns.”

Ancient Greece shifted from bronze to iron 3,000 years ago and part of Lower Manhattan did the same 2,800 years later—for the same reasons.

ALANNA: Without cast iron, there is no SoHo. As we wrote:

SoHo boasts the greatest collection of cast iron structures in the world. Approximately 250 cast iron buildings stand in New York City and the majority of them are in SoHo. Cast iron was initially used as a decorative front over a pre-existing building. With the addition of modern, decorative façades, older industrial buildings were able to attract new commercial clients. Most of these façades were constructed during the period from 1840 to 1880. In addition to revitalizing older structures, buildings in SoHo were later designed to feature cast iron.

The area became the SoHo—Cast Iron Historic District in 1973 and a National Historic Landmark in 1978—just as we finished our book. For newcomers, “SoHo” means “SOuth of HOuston Street,” with the first syllable of “Houston” pronounced “how,” not “Hugh.”

SoHo: Chester Rapkin & Don Draper

BOB: SoHo captured the imagination, and a crucial factor was its sprightly name, which originated with urban planner/theorist/economist Chester Rapkin. His 1962-63 study, “The South Houston Industrial Area: Economic Significance and Condition of Structures in a Loft Section of Manhattan” (aka, “The Rapkin Report”) likely saved SoHo from the wrecking ball. [Both Chester Rapkin and I earned PhDs in economics at Columbia (decades apart), and he taught in Columbia’s School of Architecture and Fine Arts, where Alanna was a cataloger (years apart).]

Intentionally or unintentionally, the name was a brilliant case of branding—like “Lucky Strike” or “McDonald’s.” Would “the South Houston Industrial Area” have captured anyone’s imagination? 1962-63 was the Golden Age of Advertising. In TV’s Mad Men, branding genius Don Draper says in 1965, “Make it simple, but significant.” In The Founder, Ray Kroc (Michael Keaton) purchases McDonald’s in 1961 and explains its magic to Dick McDonald:

“It's not just the system, Dick. It's the name. That glorious name, ‘McDonald's.’ It could be, anything you want it to be... it's limitless, it's wide open... it sounds, uh... it sounds like... it sounds like America.”

“SoHo,” too, is anything you want it to be. It recalls London’s Soho theater district, but the capital “H” says, “We’re different.” It rhymes with “boho” (“bohemian”), a 1958 neologism which suggests Bob Dylan in the 50s and 60s or Debbie Harry in the 70s. (Dylan played a peripheral role in saving SoHo from demolition, and Harry attributed her first public recognition to photos published in the SoHo Weekly News.)

After 1963, such names proliferated in NYC. There’s TriBeCa (TRIangle BElow CAnal), NoHo (NOrth of HOuston), NoMad (NOrth of MADison Square), NoLIta (North Of Little Italy), DUMBO (Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass), and others, but none so famous as SoHo. On TV’s How I Met Your Mother, Lily and Marshall are excited to buy an apartment in the fictional "DoWiSeTrePla" till they realize this stands for DOwnWInd of the SEwage TREatment PLAnt.

David and Goliath, Jacobs and Moses

BOB: SoHo was nearly demolished, along with Little Italy and Chinatown. “Master Builder” Robert Moses wielded near-dictatorial power over New York’s infrastructure for decades. He was a modernist in the worst sense of the word. He thought government had a right to bulldoze inconvenient neighborhoods, destroy communities, and herd residents into soulless high-rises.

In SoHo, Moses was laid low by the genius, charisma, and determination of Jane Jacobs and her largely female army of activists. (Moses said nobody opposed his plans except for “a bunch of mothers”—including Jacobs) Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) shows a remarkable understanding of the factors that separate lively, safe, functional neighborhoods from the dead, crime-ridden, dystopian wastelands that Moses painted with bulldozers, cement, and asphalt.

In 1958, Moses aimed to run an expressway through the middle of New York University. Activists shut him down—an enormous blow to his prestige. In TV’s The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Midge happens upon a rally in Washington Square Park and, pulled onstage by Jane Jacobs, gives a rousing speech on the controversy. “How Accurate was the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel at Washington Square Park?” compares the episode with actual history and notes that Jacobs participated in that action but wasn’t the principal leader. (Shirley Hayes—another mother—was.)

Four years later, Jacobs was the undisputed leader of Lower Manhattan’s preservationists. Her battle with Moses is described by James Nevius in “Jane Jacobs, Robert Moses, and the Battle Over LOMEX.” See also Amazon Prime’s fine documentary, Citizen Jane: Battle for the City (2016).

Jacobs collaborated with Bob Dylan to write a protest song, “Listen, Robert Moses.” It’s not Dylan’s best, and I’m not sure it was ever recorded. (A YouTube recording seem to be someone else’s melody applied to the lyrics.) A splendid miniseries, The Offer, portrays the making of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. Much of The Offer centers on Coppola’s insistence that the film be shot Little Italy for authenticity. If Moses had had his way, Coppola’s masterpiece couldn’t have happened.

ALANNA: Our book noted that in 1962, the City Club of New York published a a report called The Wastelands of New York City that viewed SoHo as a “commercial slum”:

“After this report, plans for the Lower Manhattan Expressway were revived by … Robert Moses. The roadway would have cut directly through SoHo, driving merchants and artists out of the area, and indiscriminately demolishing many stunning examples of 19th century cast iron architecture.”

Rent Control and Looking the Other Way

BOB: Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck said, “in many cases rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing.” Artificially low rental incomes discourage maintenance, leading to physical deterioration and abandonment by owners and tenants. Rent control had a more salubrious effect in SoHo. The buildings were too old to sustain modern manufacturers. Moses wasn’t wrong in assuming that that narrow streets impeded industrial rejuvenation.

Low rents enabled artists to obtain vast lofts for producing monumental paintings and sculptures. They began living in those spaces—illegally. The city faced two choices: (1) Evict the artists and leave SoHo an unoccupied wasteland, or (2) Look the other way and allow organized, albeit unlawful, civic life. The city mostly chose the latter, though artists were never at ease.

ALANNA: In her review of our book, Vivian Raynor wrote:

“The pioneers were willing to live uncomfortably, as well as illegally, skulking out at night to put garbage in public baskets, using gas‐station bathrooms and generally improvising as they built their studios (what a musical it would make!)”

I had a sense that perhaps I shouldn’t be telling anyone about this corner of Manhattan. I didn’t want it to change or reveal who was living there “illegally,” while paying practically nothing for living space. My interviews involved some of the most memorable people I’ve ever met. Many didn’t want it known they lived there, but I pursued them and honored their privacy.

When I visited SoHo, I saw artists carrying huge canvases, sculptural material, recording equipment, and musical instruments. Few boutiques or galleries existed. There were only a few music/dance/theater venues hidden behind the façades. The area had a sense of mystery and a vibrant underculture—but no bright lights or printed professional signage. Advertisements were handwritten on paper and posted on doors, poles, and walls. The only neon I saw was on a very small store called “Let There Be Neon.”

The Characters

ALANNA: I interviewed Rashied Ali, free-jazz musician, avant-garde drummer, and sideman to John and Alice Coltrane. We met in a dark staircase in his building. He sat at the top of the stairs, and I was at the bottom, asking questions and listening to his music.

One day, Helene and I walked the area, heard music, and meandered into “The Kitchen,” where Philip Glass was presenting a dance performance. During the multimedia stage of my research, long before the book, I interviewed an older man who stood outside of his building. After explaining what I was doing, he told me about his life in this area—growing up on its mean streets. He must have been about 80—one of the few who experienced the SoHo of the late 19th and mid-20th centuries.

The Genesis of the Guidebook

ALANNA: My life with SoHo began when I was getting a Master’s in Library Science in the early 1970s. We needed a culminating project, so I did a multimedia presentation on SoHo, which was just coming into its own. My project included audio and video interviews of artists and residents, photographs, and research on architecture and history. I found that many façades once covered up wooden structures which readily caught fire. So many firefighters were killed, that the area became known as “Hell’s Hundred Acres.” The area has undergone so many changes—with bordellos, Union soldiers, fine department stores, and theaters. Each brought different clienteles. Niblo’s Garden, built three times, gave P.T. Barnum his start.

I immersed myself in the neighborhood and conversations with its unconventional residents. When I discussed this project with Helene Seeman and showed her my photos and research, her eyes lit up. She immediately wanted to collaborate on documenting these treasures, and the result was the book.

Helene was assistant director of the Louis K. Meisel Gallery, one of the pioneering SoHo galleries. Louis and Susan Meisel opened their gallery in 1973, which must have been a great financial risk, but fifty years later, the gallery is still there. Louis Meisel coined the term “photorealism,” which was the polar opposite of the abstract expressionism—in a good way.

Helene’s task was to get interviews with artists and visit their warehouses and loft spaces. Thanks to her, we met everybody. I tackled the music, theater, and dance scenes, the historical research, and the photographs. The cover is a story unto itself. I wanted to show both the cast iron buildings and the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers, which had just been completed. I’m no daredevil, but that photo required me to lean far over a rooftop ledge, with Helene holding my legs to keep me from toppling from the building. It wasn’t quite Harold Lloyd’s clock in Safety Last! (1923), but it’s the closest I’ll ever get.

The CIA as Curator?

BOB: In the 1990s, the story emerged that the Cold War-era CIA played a key role in popularizing abstract expressionism. The idea was to contrast the movement’s wild, free spirit with the dreary Socialist Realism promoted by Soviet Bloc nations. Supposedly, the CIA laundered money to fund abstract expressionism, which, if true, would have fueled the market that made SoHo, in the words of Alanna and Helene, “the largest concentration of avant-garde art in the world.”

Lucie Levine’s “Was Modern Art Really a CIA Psy-Op?” details the theory, which involves the Rockefeller family and their godchild, the Museum of Modern Art. In that article, MoMA Executive Secretary and CIA cultural administrator Thomas Braden said he was glad that the CIA was “immoral” because its arts promotion “won more acclaim for the U.S. … than John Foster Dulles or Dwight D. Eisenhower could have bought with a hundred speeches.” In “Modern Art Was CIA ‘weapon’” Frances Stoner Saunders quoted Donald Jameson, a former CIA operative directly involved in the program. He joked that:

“Regarding Abstract Expressionism, I'd love to be able to say that the CIA invented it just to see what happens in New York and downtown SoHo tomorrow! … But I think that what we did really was to recognise the difference. It was recognised that Abstract Expressionism was the kind of art that made Socialist Realism look even more stylised and more rigid and confined than it was.”

David Rockefeller was CEO of Chase Manhattan Bank, where I worked in the 1980s, and our 60-story tower was jammed full of abstract expressionist masterpieces—and with quite a few ex-CIA officers.

ALANNA: Our book long predated the CIA rumors, but, if true, that would be an interesting twist. The artists I met would probably not have been big CIA fans.

From After Hours to Escape from New York

BOB: In 1985, Alanna and I saw Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece, After Hours—a nightmarish tale of an anodyne Upper East Sider who visits SoHo one evening to meet a woman staying in an artist’s loft, quickly decides she is disturbingly strange, and decides to go back home. For the rest of the film, his desperate quest to simply get on the subway and return home is frustrated at every turn by an angry cabbie, a callous subway attendant, oafish thieves, a vengeful waitress, a shocking suicide, sadistic punk-rockers, a violent mob led by an ice cream truck driver, and strips of papier-mâché. When the film ended, I turned to Alanna and said, “You do realize, don’t you, that this film is only a slight exaggeration of our actual life here in New York?” She agreed, and with that, we plotted our move from New York to Virginia, which finally occurred in 1988.

ALANNA: It was exciting to walk these streets, feeling a sense that I needed to capture this moment in time before it started changing, as every place does in Manhattan. I took thousands of photographs while wandering the dark, filthy, lonely, quiet streets. Sometimes, my father, who died before the book came out, accompanied me, because he was uncomfortable about my going alone. One evening, I went to a loud, crowded SoHo party. When I left and stepped onto the street, it was lonely and terrifying—such a contrast to those seemingly safe daytime streets. When Bob and I rewatched After Hours recently, it brought back that unsettling feeling.

SoHo after SoHo

BOB: In the decades since Alanna co-wrote Soho, the neighborhood has undergone yet another transition. In its most exaggerated telling, wealthy art-lovers moved into the neighborhood to be close to artists and, in doing so, pushed rents up, driving artists out. It’s not entirely true, though it’s not entirely untrue. At SoHoMemory.org, Yukie Ohta described recalled:

“SoHo used to refer to ‘the other side of the tracks,’ where poor artists lurked in the shadows in fear of being evicted, where people from uptown went ‘slumming.’ But now the name SoHo is used as an adjective to describe an aesthetic or a lifestyle that is glamorous and hip with a dash of bohemia mixed in, as in SoHo-style loft or SoHo chic. The name SoHo has gone from describing an industrial wasteland to the stomping grounds of the rich and fabulous.”

ALANNA: In closing, I should say that it has been many years since we were last in SoHo. We just may have to pay a visit to see how things have changed.

Lagniappe

The two of us often do art/music collaborations, as in this jazz/abstract expressionist interpretation of the 59th Street/Queensboro Bridge.

After being certain for half a lifetime that it is pronounced SoHo rhyming with Mojo, I'm supposed to start rhyming with Sough How? Not gonna happen. I'm sticking with Mojo, and feel confirmed in that choice by your article that so beautifully transmits the mojo of SoHo.

Really enjoyed your SoHo article. But ain’t it grand being from the South!