Son, Sun, Kronos, Kairos

Total solar eclipse and musings on God, probability, time, and turpentine

SON AND SUN

Across my 70 years, two memories stand out above all others. Both are of mystical, magical, miraculous events that lasted only a few minutes. Each was preceded by long hours of anticipation and followed by a lifetime of contemplation and near-disbelief. The most intense memory is that of watching the birth of my son in 1986. A close second was watching a total eclipse of the sun in 1970. The Universe was kind enough to allow me to witness two of the most unlikely physical occurrences imaginable. Each time, that same Universe whispered in my ear, “Enjoy the sights of this journey, but do not think for a moment that I am within your comprehension.”

Today, April 8, 2024, I will be in the wrong locale to see this afternoon’s total solar eclipse. It is highly unlikely that I shall see the next one to cross the United States (August 2044 in Montana and North Dakota). No matter. Whatever course my life may take from this moment forward, I am forever part of a select Fellowship—that thin crescent of mankind that has witnessed the most improbable of celestial events—the moon’s total devourment of the solar disk.

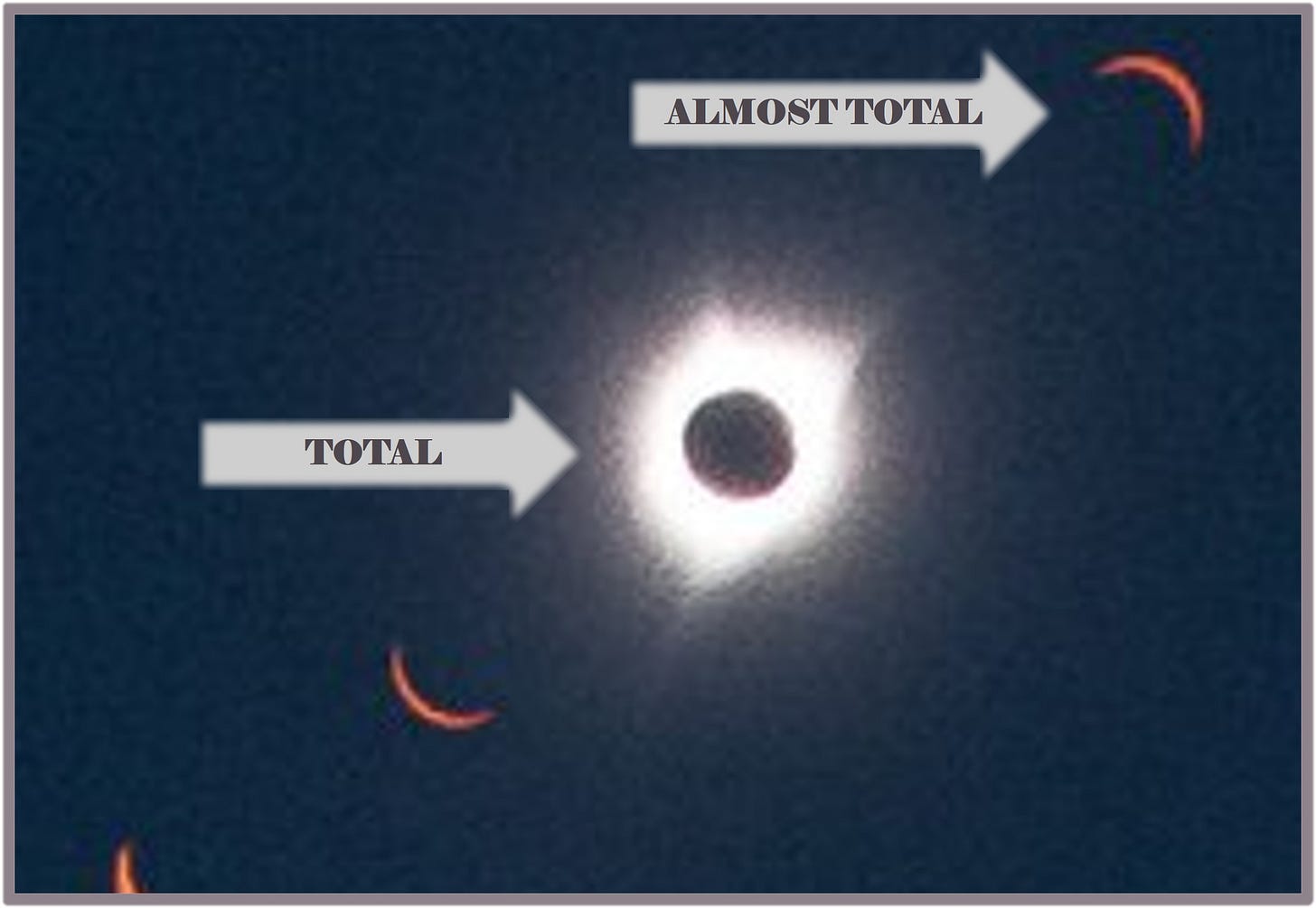

If you have witnessed only a partial eclipse, I regret to inform you that you are not part of the Fellowship. NASA’s time-lapse photo above (the center portion of which is reproduced below) hints, but only hints, at the stark difference between 99.9% and 100% total.

Since those intensely remembered minutes in 1970, I have only read two articles that do justice to the impact of totality. One is “A Total Solar Eclipse Feels Really, Really Weird,” by astronomy writer Bob Berman. (The other, by essayist Annie Dillard is described at length at the bottom of this page.) Berman wrote:

“Actually, seeing an almost total eclipse is no better than almost falling in love or almost visiting the Grand Canyon. Only full totality produces the astonishing and absolutely singular phenomenon that resembles nothing else in our lives, on our planet, or in the known universe.”

Berman described the intensity and uniqueness of the experience:

“Have you ever witnessed a total solar eclipse? Usually when I give a lecture, only a couple of people in an audience of several hundred people raise their hands when I ask that question. A few others respond tentatively, saying, ‘I think I saw one.’ That’s like a woman saying, ‘I think I once gave birth.’”

In a 2017 essay, I described my own feelings:

“At 99 percent total, the eclipse was pretty interesting. A bluish veil descended over earth, birds made night sounds and the few passing cars had their lights on. But the moment the eclipse reached 100 percent totality was incomparably different from the view a split second earlier—surreal beyond imagination. … Shadow bands—wavy lines like ripples on a pond—stretched for miles across the landscape. The corona surrounding the blackened moon was a ring of pure white brilliance resembling burning magnesium.”

Berman described the astronomical unlikelihood of this particular astronomical event:

“No discussion of totality should omit the strange science lurking behind it. It starts with a bizarre coincidence: the moon is four hundred times smaller than the sun, but it also floats four hundred times nearer to us. This makes the two disks in our sky appear to be the same size. Now, if the moon appeared larger than the sun, it could still occasionally stand in front of it, but it would also blot out the dramatic prominences along the sun’s edge, those geysers of pink nuclear flame. So for maximum amazingness, these bodies must have identical angular diameters—i.e., they must appear to be the same size. And they do.

The moon wasn’t always where it is now, which makes the coincidence even more special. The moon has really just arrived at the “sweet spot.” It’s been departing from us ever since its creation four billion years ago, after we were whacked by a Mars-size body that sent white-hot debris arcing into the sky. Spiraling away at the rate of one and a half inches per year, the moon is only now at the correct distance from our planet to make total solar eclipses possible. In just another few hundred million years, total solar eclipses will be over forever.”

Precocious from the get-go, I had known these facts since I was perhaps 6 or 7 years old. My father, who was largely self-educated, had a large collection of astronomy books, a good telescope, and a passion for the subject that he passed along to his sons. In the early 1960s, I saw in one of my own astronomy-for-kids books that a total solar eclipse would pass a few hours south of my home on March 7, 1970. I swore then that I would be in the path of totality that day, and I kept that promise to myself.

My wife and I originally had reservations to see the 2017 and 2024 eclipses in Oregon and Texas, but we decided in both cases that totality in the Internet Era was best left to the young. In 1970, my friends and I hopped in a car sometime after 9:00 a.m. and drove the 120 miles to Tarboro, North Carolina in around two hours. Traffic was negligible, and as totality approached, we just pulled off the road into a field and watched the heavens with no one else in sight. An eclipse was an event for the few and the astronomically committed.

In the Internet Era, every inch of each eclipse’s path of totality is stuffed with spectators, and roads for many miles in either direction are jammed with thrill-seekers in a sort of Woodstock/Burning Man/Fyre Festival stretched thin across hundreds of miles. Alanna and I concluded that we were not made for such mob scenes and canceled our reservations both years.

KRONOS, KAIROS, AND THE CONCEALED FACE OF GOD

Throughout my life, my religious views have rested easily on humble ignorance. Perhaps a higher power designed the Universe, or perhaps it’s all just the result of happenstance and insentient physical processes. Perhaps a higher power made the Universe and then stepped away, or perhaps that higher power intervenes in minute, meticulous ways. I just don’t know, and, paradoxically, my ignorance of such matters gives me comfort. But on that afternoon in March 1970, I watched as the moon precisely blotted out the face of the sun and thought with near-certainty, “I don’t think this is accidental.”

A passing thought at that moment (which amused me even at the time) was the notion that the Universe might be merely an illusion, created specifically for my personal benefit and entertainment. (Or, less solipsistically, created for all humanity’s collective benefit). If one day, my Maker tells me face-to-face that that the world and the Universe were all just a simulation, I expect my response will be, “Yeah, I kind of figured that out on a Saturday afternoon in 1970.”

But in reality, the lesson I carried from these memories was neither a confirmation of faith or a denial of faith but, rather, a joy and wonderment at my inability to know the larger truths. Exodus 33:11 says that:

“The LORD would speak to Moses face to face, as one man speaks to another.”

But in Exodus 33:20 God tells Moses:

“you cannot see My face, for man may not see Me and live.”

In the Book of Esther, the name of God is nowhere to be found, but, some have argued, that omission is proof that the Book of Esther is entirely about God. Concealment, in this view, does not imply absence and may, in fact, imply the opposite. In “The Garden of Forking Paths,” Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges describes a massive (fictitious) Chinese novel in which the word “time” does not appear at all—proof positive, a fictitious reviewer suggests, that time is itself the very subject of the novel.

The Ancient Greeks had two distinct concepts of time—kronos (κρόνος) and kairos (καιρός), and my two paramount memories—the birth of my son and the eclipse of the sun, were drenched in kairos. Kronos is objective, and kairos is subjective. Chronological Time ticks by relentlessly, mindless of human events; every day is equal to every other day. Kairological Time is anthropomorphic; some days, some moments contain more time than others. The professor from whom I learned the distinction used the example of November 22, 1963: for those of us who could recall the Kennedy assassination a decade after the event, that day was far longer than any other day.

The professor who introduced me to Borges and to kronos/kairos also introduced me to the most profound work of fiction I ever read—William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury. The first quarter of the book is seen through the eyes of Benjy Compson, a mentally disabled boy who is unaware of chronological time and lives only in a dozen or so moments of kairos. Some have interpreted his character as a sort of Lamb of God—an utter innocent outside the usual travails of mankind. Witnessing my son’s birth and the total solar eclipse both gave me the sense of the helpless befuddlement that Faulkner gave to Benjy.

A STRONG SMELL OF TURPENTINE

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.—father of the Supreme Court justice—attempted to gaze upon the secrets of the Universe, using psychotropic drugs as his portal into the unknown realm. Holmes, Sr., was a physician and an early adopter of ether as an anesthetic for surgical patients. He wished to understand the experiences of his patients, and particularly any metaphysical insights conferred by such an elevated mental state. So he gave himself a good dollop of ether and slipped into twilight. In a lecture, he explained the insight revealed to him—the central nature of the Universe:

“The veil of eternity was lifted … The one great truth which underlies all human experience, and is the key to all the mysteries that philosophy has sought in vain to solve, flashed upon me in a sudden revelation. Henceforth all was clear: a few words had lifted my intelligence to the level of the knowledge of the cherubim.”

As he emerged from his stupor, Holmes scribbled “the all-embracing truth still glimmering in my consciousness” on a sheet of paper. When he was fully awake, he returned to his desk and found that this truth, scrawled in his own handwriting, was simply:

“A strong smell of turpentine prevails throughout.”

Dr. Holmes’s drug-induced epiphany was on par with the “insights” that my college classmates gained from marijuana and LSD. Laughing publicly at his own folly, Dr. Holmes abandoned his quest for chemically revealed cosmic truths. Likewise, the two great memories of my life—sun and son—offered me no eternal answers, but have brought me a lifetime of joy at the absence of such answers.

ANNIE DILLARD & MARIA POPOVA

Essayist Annie Dillard wrote a long, lovely essay on having witnessed a total solar eclipse. It’s in her book, The Abundance and also appeared in The Atlantic. Dillard’s essay and more on total eclipses are, in turn, described in a long, lovely essay by Maria Popova: “Into the Chute of Time: Annie Dillard on the Stunning Otherworldliness of a Total Solar Eclipse.” From Dillard:

“Seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane. Although the one experience precedes the other, it in no way prepares you for it.”

and

“The sky’s blue was deepening, but there was no darkness. The sun was a wide crescent, like a segment of tangerine. The wind freshened and blew steadily over the hill. The eastern hill across the highway grew dusky and sharp. The towns and orchards in the valley to the south were dissolving into the blue light. Only the thin band of river held a spot of sun.

Now the sky to the west deepened to indigo, a color never seen. A dark sky usually loses color. This was saturated, deep indigo, up in the air.”

and

“I turned back to the sun. It was going. The sun was going, and the world was wrong. The grasses were wrong; they were now platinum. Their every detail of stem, head, and blade shone lightless and artificially distinct as an art photographer’s platinum print. This color has never been seen on earth. The hues were metallic; their finish was matte. The hillside was a nineteenth-century tinted photograph from which the tints had faded. All the people you see in the photograph, distinct and detailed as their faces look, are now dead. The sky was navy blue. My hands were silver. All the distant hills’ grasses were fine-spun metal which the wind laid down. I was watching a faded color print of a movie filmed in the Middle Ages; I was standing in it, by some mistake. I was standing in a movie of hillside grasses filmed in the Middle Ages. I missed my own century, the people I knew, and the real light of day.”

Robert F. Graboyes publishes Bastiat’s Window, a Substack journal of economics, science, and culture—with an emphasis on healthcare. He is a health economist, journalist, and musician in Alexandria, Virginia, and holds five degrees, including a PhD in economics from Columbia University. In 2014, he received the Reason Foundation’s Bastiat Prize for Journalism. His music compositions are at YouTube.com/@RFGraboyes/videos.

I have always liked the comparison (adapted from Mark Twain) that a partial solar eclipse is to a total solar eclipse as lightning bug is to lightning.

> It starts with a bizarre coincidence: the moon is four hundred times smaller than the sun, but it also floats four hundred times nearer to us. This makes the two disks in our sky appear to be the same size.

> ...

> The moon wasn’t always where it is now, which makes the coincidence even more special. The moon has really just arrived at the “sweet spot.” It’s been departing from us ever since its creation four billion years ago ... the moon is only now at the correct distance from our planet to make total solar eclipses possible. In just another few hundred million years, total solar eclipses will be over forever.

The fact that such an aesthetic marvel exists only fleetingly — on a cosmic timescale at least — precisely during the period of time when we will be here to appreciate it, is only "bizarre" or "coincidental" for those who lack eyes to see...