Ten Brief Tales from the Spirit-World

Memories distilled from across a lifetime. Plus, one vintage story.

At his excellent Substack, Glenn Reynolds just published “And Now for Something Completely Different,” a description of the field trip he and students took to a whiskey distillery for their Law of Distilled Spirits class. He teaches at the University of Tennessee College of Law and, as his piece notes, his offerings in recent years have included “space law, firearms law, national security law, and Internet law, as well as, long ago, International Business Transactions.” (Subscribe to his Substack, and you’ll be served a flight of all of these things.)

As explained in his distillery piece, his course covers a dizzying array of legal topics: taxes, regulation, trademarks, zoning, fire safety, and more. It’s a short and interesting read into the army of lawyers who reside in every bottle of whiskey produced and/or sold in America. I don’t drink all that much but have always enjoyed the products of distillation—single malt and gin, in particular. Reading his piece has persuaded me not to open a distillery (not that I ever would have) and given me an appreciation for those do.

Reading the essay reminded me of eight of my own whiskey stories—plus one wine story. My stories include a fair amount of public policy oddities, but also some quaint recollections of my own. So, here’s mud in your eye.

THE LADY TASTING BOURBON

Terry, a revered friend and faculty member at the University of Richmond, specialized in the study of distilleries—a wise career choice in that it took him to Ireland, Scotland, Japan, and other scenic bastions of distilled goods. Once he told me of the CEO/owner of a renowned Tennessee establishment (Jack Daniel’s, I believe), who had a rule when entertaining at his home. Guests were forbidden to pour water into his whiskey, but it was fine for them to pour his whiskey into water. His logic was that in the first case, you were taking a superior product and making it worse, whereas in the second case, you were taking an inferior product and making it better.

The story reminds me of a landmark event in the development of statistical inference tests. An English academician claimed she could tell whether milk was poured into tea versus tea poured into milk. Chemists and physicists present said that was impossible—that there would be no detectable difference in the two. To test the veracity of her claim, her future husband, along with statistical genius Ronald Fisher, devised on the spot what would become known as the Fisher’s Exact Test. Fisher wrote of the test, but omitted how well she did at identifying the differing cups. Asked about those results after Fisher’s death, attendees said she got every single cup correct. The incident is described splendidly in The Lady Tasting Tea: How Statistics Revolutionized Science in the Twentieth Century, by David Salsburg.

IN THE HOT SEAT

In 1960s Virginia, liquor-by-the-drink was forbidden until I was approaching drinking age (18 in those civilized days). Some localities went through peculiar progressions of legal restrictions. Where I lived, for example:

For a while, mixed drinks were possible only at private clubs where drinkers brought their own bottles.

Then restaurants were allowed to serve drinks, but only to patrons seated at tables. If you wanted to move to another table, you had to ask a waiter to carry the drink for you from one table to the other—apparently to discourage barbaric rowdiness.

Then, you were allowed to carry drinks between tables, but you had to be seated when ordering—not standing at the bar, for example. Restaurants soon skirted this law by creating a “hot seat” at the bar. Patrons would walk up and sit briefly on the hot seat and shout their order to the bartender. Then they would jump up to make way for the next drinker.

Then, the state said the hell with it and abandoned all these bizarre restrictions—other than the continuing state monopoly on liquor stores.

I suspect that a good number of the legislators responsible for this hair-splitting legislation were not entirely observant of the rules they laid down.

SMILE WHEN YOU SAY THAT

After Virginia had abandoned its array of odd little drinking restrictions, I ventured southward from Virginia to North Carolina and went with a cousin to a tavern. Forgetting that liquor-by-the-drink was still illegal south of the border, I called out to the waiter, “I’ll have a Scotch, please.” The entire place went silent, and all heads turned to me with a look of alarm—like a scene out of some Western, where a newcomer inadvertently says something that insults the town’s ruthless cattle rustler.

THEY’LL BE COMING ROUND THE MOUNTAIN

During those years of odd and myriad local restrictions, I had friends living in the mountainous vicinity of the tripoint where Tennessee, Virginia, and North Carolina meet. I don’t know what the laws down there are these days, but back in the day, the counties of those states were still emerging from the repeal of Prohibition and comprised a patchwork of bizarre and wildly differing proscriptions on how, where, when, and whether alcohol could be served and drunk. Some forbade all Sunday sales, beginning at midnight Saturday. Others required sales to cease at other hours. Some allowed mixed drinks. Some allowed only beer and wine. Some mandated low-alcohol (3.2%) beer. Some forbade alcohol altogether. There were other intricacies that escape my memory. The effect of this was to incentivize drinkers—especially on Saturday night/Sunday wee hours—to go on long journeys along dark, winding mountain roads in order to procure the beverages of their choice at the hours of their choosing—with options changing as the hours ticked by. I’m quite sure that mid-20th-century liquor laws claimed a lot more lives than the geographically coincident Hatfield-McCoy feud ever did.

THOSE WHO CANNOT DO, TEACH

I knew of an academic who was an expert on the alcohol industry, including the distilled spirits sector, but who was himself a devout teetotaler. One of his students, who was not at all enamored of him, told me that he had a problem with the professor’s choice of expertise. “Why is that?” I asked him. He said, “To me, it’s like a priest from a celibate order operating a sex-advice hotline.”

FIDDLER ON VERMOUTH

A large percentage of American Jews trace their ancestry to the shtetls of Eastern Europe. Our modern image of these small towns is that of an impoverished, ramshackle, godforsaken village in Russia’s Pale of Settlement. This perception is especially informed by the writings of Sholem Aleichem and the Broadway show, Fiddler on the Roof, based on his tales. This dismal image of the shtetl was correct from the mid-nineteenth century on, but that was a later manifestation—the one that Jews fled from when they came to America.

In The Golden Age Shtetl: A New History of Jewish Life in East Europe (Princeton University Press, 2014), Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern says that from the 1700s through the mid-1800s, the shtetls were prosperous towns. A considerable part of the wealth derived from the fact that Polish/Lithuanian kings had granted certain individuals monopolies on the production and sale of vodka—an especially important product in that part of the world. Many of these monopolists invited Jews to settle on their estates—on the condition that they bring commerce to the towns and trade in liquor. In time, many of these Jewish businesspeople themselves became affluent distillers and tavernkeepers—living in fine brick homes. Things went rather well until Russia took these lands away from Poland and soon became paranoid and despotic about all things Polish and all things Jewish. This is when the affluent tradesmen become the poor village-dwellers of Fiddler on the Roof.

Both of my grandfathers became, for a time, tavern-owners and/or bartenders after immigrating to the United States. I suspect that they might well have come out of this earlier tradition. The photos below show my maternal grandfather in his tavern-keeping days in Key West, Florida, sometime between 1909 and 1914. My paternal grandfather owned a hotel in Philadelphia, and my father fondly recalled him mixing elaborate, colorful, multi-layered pre-Prohibition libations. My wife’s great-grandmother owned some sort of tavern in Europe, and today, we still own a short-necked banjo used by the house musicians in her establishment.

PROHIBITION AND AMERICAN CUISINE

Until recent years, American cuisine was regarded by many as second-rate, and a good deal of the blame for that lay with Prohibition—though that era also made some positive contributions to food culture in the U.S. Fine-dining establishments were hard-hit by the Volstead Act. High-end bartending, which had become a fine art, largely vanished as a profession. Dining shifted to home cocktail parties and small speakeasies (both of which specialized in finger foods) and also to booming Italian restaurants (which discreetly served homemade wine). Restaurants shifted their creativity into nonalcoholic indulgences like fancy sodas, fruit juices, and ice cream. (My great-uncle, who owned the bar in the photo above, also opened an ice cream parlor in Florida in the first decade of the 20th century—a feat that depended upon then-revolutionary refrigeration technology.)

COLOSSUS OF ROADS

In 2019, my wife and I visited the Old Pulteney distillery in Scotland (pictured at the top of the article). I have many fond recollections of that stop, but one sticks out in particular—the waterworks they showed us on the tour. As their website says, “The water used in the making of Old Pulteney is carried from Loch Hempriggs by a lade constructed by a famous Scottish civil engineer Thomas Telford.” Telford is one of the 19th century’s greatest innovators—a builder of roads, bridges, and canals who earned the sobriquet, “The Colossus of Roads.” His story is told in depth in Paul Johnson’s The Birth of the Modern. For me, it was a thrill to actually see one of his works close up.

THE MEASURE OF A MAN

My wife said one of her most distinct memories from the single malt and gin tastings in Scotland was the puny little tastes they gave you, measured out with extreme precision in little conical jiggers. At one stop, I asked why every bartender is so obsessive-compulsive about measuring out the shots. He said, “EU regulations.” Suddenly, I understood Brexit in the most visceral way possible.

SLÁINTE MHATH

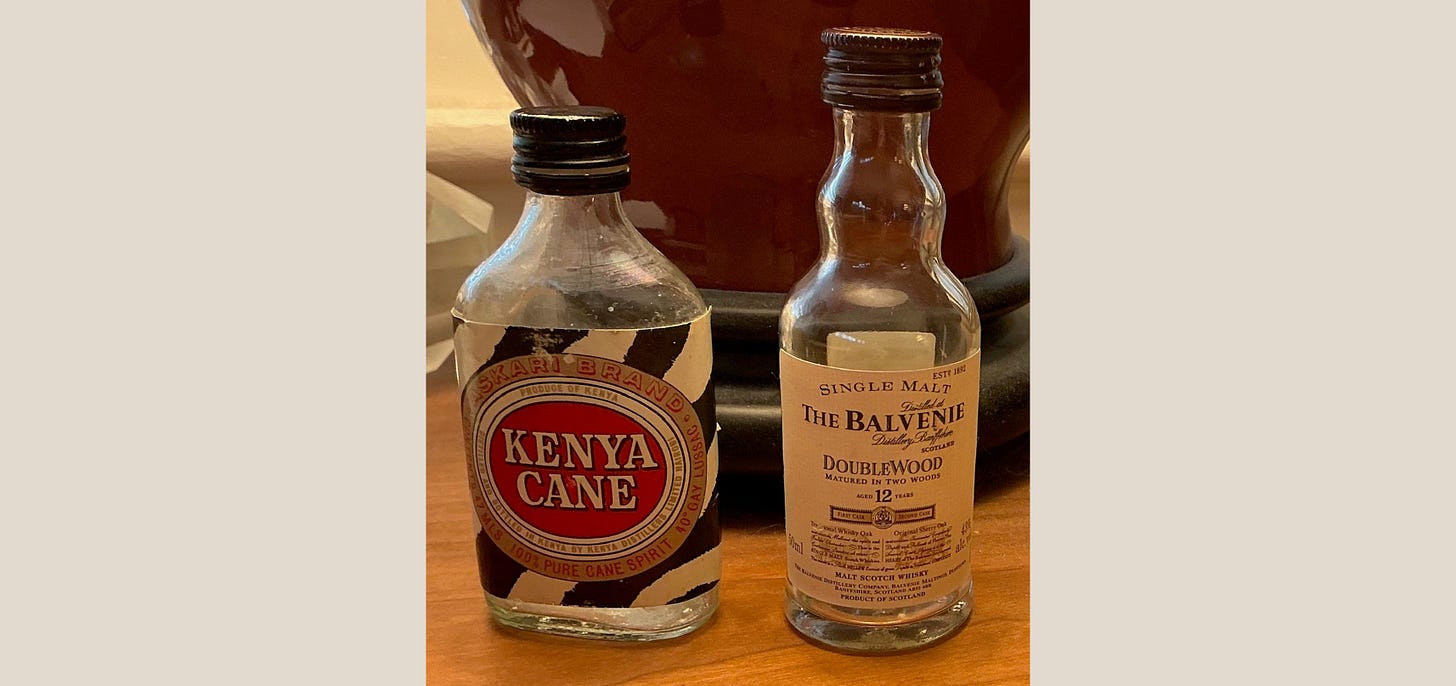

Finally, here are two bottles that have great significance to me. I drank the Kenya Cane, either in Nairobi or at the Masai Mara Game Reserve in 1984. Fiery stuff made from sugar cane (like Brazilian cachaça). People said this liquor was a malaria preventative, as any mosquito biting you would fall off dead drunk before it could infect you. (The same was said to me of Star Beer in Nigeria.)

The Balvenie 12-Year Doublewood bottle dates from 1998. My father came home from the hospital, knowing that he had only a few days left to live. I asked whether I could get him anything, and he said, softly, “Scotch!” There was none in the house, so I went to the liquor store and brought this bottle back for him The Balvenie has been my brand ever since, though I tend more toward the 14-Year Caribbean Cask these days.

A VINTAGE STORY

This is a wine story, not a whiskey story, but it fits.

While an undergraduate at the University of Virginia, I was the house musician for several fine-dining establishments. One elegant and cozy restaurant leased its building—a 19th century house—from a businessman whom I’ll call “Joe.” The week of the grand opening, Joe brought his family to celebrate the opening. He asked the bartender for a wine recommendation, and he suggested the single most expensive bottle available—a Château Lafite Rothschild that cost $150—around $1,000 in today’s money. Joe said, “Wow! Is it worth it?” The bartender said “absolutely,” and he began describing the particular characteristics of that label and vintage.

Joe ordered the bottle and said to the bartender, “I assume you’ve had this before?” The bartender said, “Unfortunately, no, I’ve never had the pleasure.” Joe said, “Well a wine expert like you ought to have the opportunity—bring a glass for yourself.” The bartender said, “No, I couldn’t.” Joe said, “I insist!” and the bartender said, “Wellllll, okay.” He sniffed it, took a sip, spun it around in his mouth, swallowed, waited, and then waxed eloquent about the notes and bouquet and highlights and hints of this and that while Joe listened, enraptured.

The restaurant owner—a diminutive and intense fellow—watched these proceedings from a distance, smiling and nodding periodically at Joe. When the bartender finished his glass, the owner did a little come-here signal with his index finger and took the bartender into the next room. He looked at him and said, “You don’t actually know s**t about wine, do you?” The bartender said, “Not one g****m thing.” The owner said, “You’re fired.”

A week later, I ran into the bartender, who told me the details of his rapid departure. I asked, “Was it worth it?” He said, “Well … I got to drink a $150 glass of wine. And I already have a new job. So you tell me.”

Re the "Coming Round the Mountain": I had a friend in Tennessee who would say, "You can't get drunk on Sunday in this county -- 'less you plan ahead."

I appreciated the stories about your grandfathers working as bartenders upon coming to America. My great-grandfather's US naturalization papers list his occupation as "saloonkeeper" which always seemed to me to be a noble occupation for an Irishman. Also, as a North Carolinian, I remember voting in 1978 to allow liquor by the drink. Being able to order a cocktail in virtually any county in the state now seems normal but back then it was earth-shattering.