That the Past Shall Not Grow Old

On the challenge of making history memorable and contemporary

If you’re not already a subscriber to Bastiat’s Window, please sign up for a free or paid subscription. (Paid really helps!!) And by all means, share the site and its articles with friends and colleagues.

I’m writing a piece, not yet finished, on early 20th century eugenics. My interest isn’t in merely documenting bygone curiosities, but rather in suggesting the lessons that that episode bears for our own time.

George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” William Faulkner’s thematically similar quote was, “The past is never dead. It's not even past.” For the documentarian or analyst, however, the problem is that the language, dress, and aesthetic of the past can render it dead and forgettable when it ought to be living and menacing. The challenge is to make the past familiar—and visceral—to contemporary audiences without compromising its veracity.

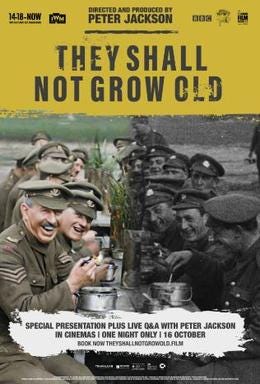

In a recent Substack Note, I referenced the masterful job that film director Peter Jackson did on this score with World War I—a conflict whose powerful lessons for today are often obscured by the darkly comical appearance of its documentary relics. Below is a review I wrote in 2019 on Jackson’s monumental achievement.

They Shall Not Grow Old—Restoring the Battlefield, Not the Film

Robert Graboyes, published February 13, 2019, by InsideSources.

World War I lives today only in the childhood memories of a few centenarians. The rest of us must remember it vicariously. With his recent documentary, “They Shall Not Grow Old,” director Peter Jackson makes that possible as never before.

For those of us born in the decade after World War II, that later war was terrifying, exhilarating and endlessly fascinating — partly because of the riveting film footage. In contrast, New York Times columnist Russell Baker, born a few years after WWI, wrote in 1981 that, “To children of the 1930s, World War I, though it had ended only 15 or 20 years earlier, already belonged to ancient history. I marveled that my parents had been alive when it was fought. It made them seem very, very old.” Its photos, he wrote, seemed “blurred and lifeless,” its uniforms “almost comically quaint,” its airplanes “antediluvian.”

WWI-era motion picture technology helped distort the perception of a war that killed 16 million human beings. For the first time, distant civilians could see battlefields as moving imagery, but those same images gave the slaughter a comic-opera mien.

Those films are jerky, gray, scratchy and silent. Jackson said combatants were “trapped in a Charlie Chaplin world.” With only 12 or so frames a second (versus today’s 24), soldiers march in an awkward, rapid-fire manner that recalls mid-1980s Super Mario Bros. animation. Slow the film down, and soldiers bounce surreally like Buzz Aldrin on the moon.

Jackson alters the viewing experience via 21st-century technology. Meticulously researched color bathes soldiers, equipment and landscape. (One reviewer found it startling to recall that battlefield skies were blue.) Flashes, scratches and distortions of aging film disappear. Contrast and detail return to under- and overexposed segments.

Mid-century recordings of WWI veterans gently narrate the relentless story arc over constant background noise of gunfire and explosions. (When the artillery falls silent at Armistice, viewers realize how numbed they had become to the din.) This, in turn, is layered over the sounds of men talking and going about their daily routines. Sometimes, the voices sync perfectly with moving lips onscreen. Lip-readers analyzed what the soldiers were saying, and accent-appropriate actors dubbed the long-still voices — just often enough to persuade viewers to forget that these are silent films.

The greatest technical achievement is restoring natural motion. Jackson’s technicians interposed software-manufactured frames between the originals to bring the film up to 24 frames per second. Viewers are free to contemplate the men rather than the medium.

But this technology raises ethical questions. Is this falsifying history and doing disservice to the original filmmakers?

In the 1980s, Ted Turner colorized venerable black-and-white films like Casablanca. Critic Roger Ebert voiced the dominant reaction:

“Anyone who can accept the idea of the colorization of black and white films has bad taste. The issue involved is so clear, and the artistic sin of colorization is so fundamentally wrong, that colorization provides a pass-fail examination. If you ‘like’ colorized movies, it is doubtful that you know why movies are made, or why you watch them.”

In narration accompanying They Shall Not Grow Old, Jackson notes the impropriety of colorizing films where directors deliberately chose black-and-white over color film. (Think of 2018’s “Roma” or 2011’s “The Artist.”) WWI cinematographers, he speculates, would gladly have exchanged black-and-white for color.

Perhaps Charlie Chaplin, too, would have used color film, had it been available. But it would still be abominable to colorize The Little Tramp today. Chaplin forged his art with the materials of his time. Michelangelo didn’t have access to acrylic paint, but that’s no excuse for colorizing “David.”

But WWI film footage isn’t primarily art. In observing “David” or The Little Tramp, we strive to see the works through the artist’s eyes. While, it’s interesting to view WWI footage through the eyes of the filmmakers, most of us likely aim to see through the eyes of those who, in John McCrae’s (slightly edited) words:

“lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

loved and were loved, and now lie

in Flanders fields.”

Jackson restored the battlefield, not the battlefield photography. Doing so breathed life into the long-gone soldiers — life their loved ones could never experience in the flickering theaters of a century ago.

Lagniappe

Making the Past Up-to-Date

Here’s a piece from the curiosity cabinet of early television. Samuel J. Seymour of Baltimore claimed to be the last surviving witness of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. Ford’s Theater publicly questioned his claim, and it is unlikely that that claim will ever be proven true or false. but the fact is, Mr. Seymour, then age 5, could have attended that fateful performance of Our American Cousin on April 14, 1865 and lived to tell about it to an American TV audience on April 12, 1956. Talking about making antique events contemporary.

You and Ted Gioia are my absolute favorite Substackers. Within a couple of days you post this about film technology of the late 1910s and Ted posts about how the change in recording technology from the 1920s to the 1930 is the reason 1920s jazz aged so fast. I absolutely adored Jackson's film -- I went to see it in a theater and then bought a DVD. And I absolutely adore 1920s jazz -- pops, clicks, and all. But I wish someone could contrive to do for Bix Beiderbecke and King Oliver what Jackson did.

I’ll have to add this to my “must see” list. I avoid war films but this sounds like it would be worth the discomfort.

On a related note, not too long ago I had a conversation with a person in her early thirties. She told me that for many of her contemporaries, WWII, and especially the Holocaust, held no emotional meaning and was only something they’d read about in history class. In fact, many of them doubted the veracity of the magnitude of the savagery and inhumanity of that time. I suppose this is a repeated phenomenon. I guess it could also be a part of the reason for the antipathy many young people feel toward Israel and Jews in general.