The Economist's Mind as Beach Reading

The logic and structure of economics in three small, friendly, readable books

A Bastiat’s Window reader asked me to explain the logic of my life’s work—the field of economics—or to refer him to books that might do so in lieu of my explanation. I’ve taught economics (and its relationship to ethics) to students in more than 70 classes, but with them, there was always the luxury of captive audiences and three to six months of mandatory attention. So rather than do a halfway job here on Substack, I’ll recommend three small books that bring alive a subject that is often rendered dry and lifeless by unskilled teachers. (See the video at the bottom of this page.) In the late 1990s, I reviewed all three books in an essay published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. What follows below is an edited version of that piece.

Over the years, countless folks have asked me, “Can you recommend a good, readable book, written for laymen, that explains what economists do?” I always start by explaining that bookstores have long shelves full of books by economists, but in most, the author presents what he or she has learned from economics. The three books reviewed here explain how the authors have learned from economics. None of the three books requires readers to have any background in economics, business, or mathematics. They are:

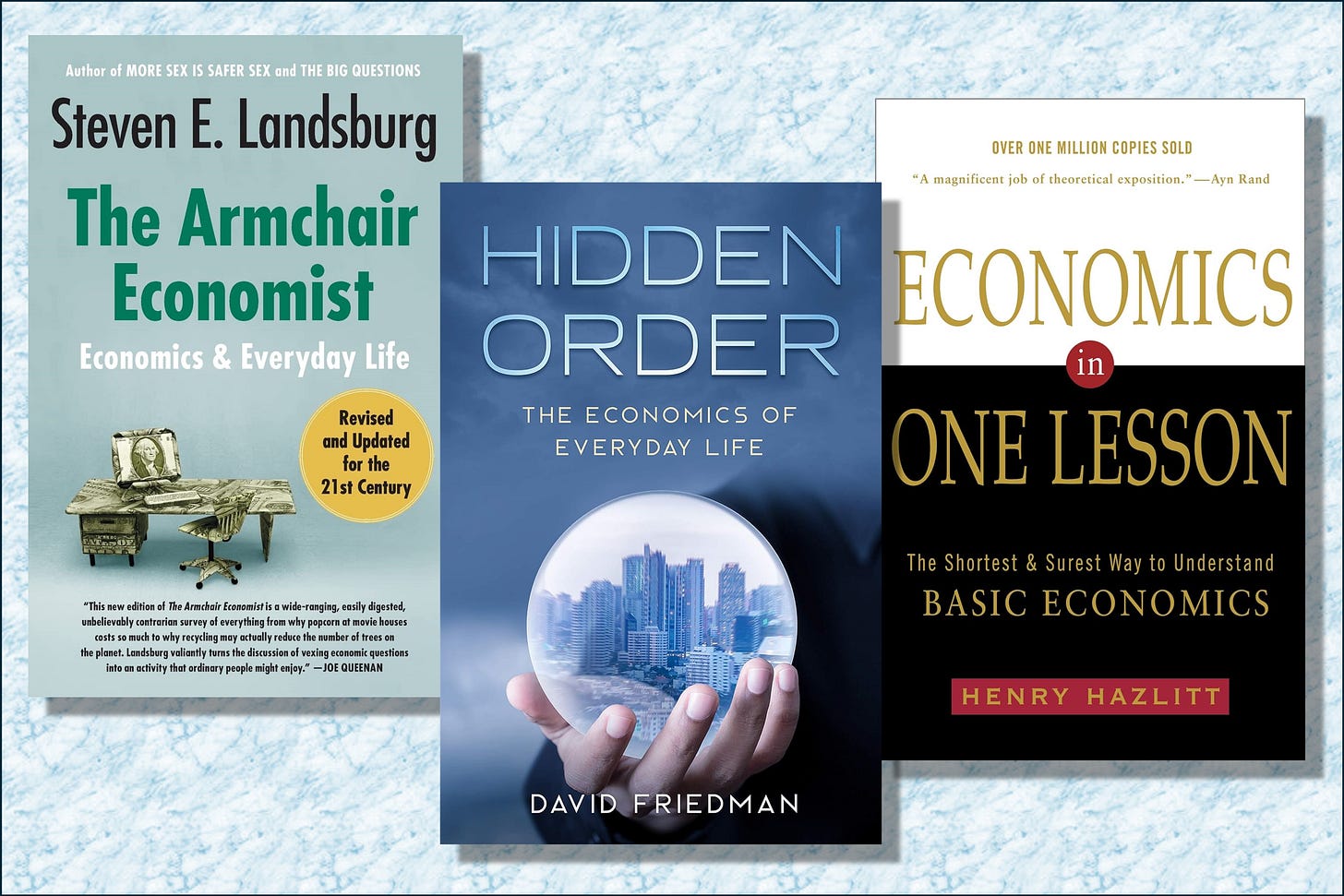

The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life, by Steven Landsburg (1st edition, 1993);

Hidden Order: The Economics of Everyday Life, by David Friedman (1st edition, 1996); and

Economics in One Lesson: The Shortest and Surest Way to Understand Basic Economics, by Henry Hazlitt (1st edition, 1946).

For anyone trying to understand what economics is all about and how economists ply their craft, these books remain my top three recommendations. After reviewing them, I’ll offer a few extra economics-for-normal-humans books that have come to my attention over the years.

THE ARMCHAIR ECONOMIST (STEVEN LANDSBURG)

The Armchair Economist is small, cheap, entertaining, informative, and intellectually solid. It gives a reader with no economics background a good idea of what economists do and how they do it. The prose is, in turn, witty, acidic, endearing, outrageous, and scholarly—but always fun. There is not one graph or equation.

Over my teaching career, I required over 2,000 students to purchase and read The Armchair Economist before arriving for the first day of class. As a result, our class discussions began on Day One at a much higher level than would otherwise have been the case.

The book bludgeons the common notion that economics is some dreary cross between accounting and necromancy—something that deals primarily with forecasting, money, and some amorphous beast known as “the economy.” Landsburg sees economics as a lens through which one can view the whole of human behavior, as summed up in his sparse opening:

“Most of economics can be summarized in four words: ‘People respond to incentives.’ The rest is commentary.”

Landsburg explores the economic aspects of human behavior in twenty-four chapters, each self-contained and none longer than a child’s bedtime story. Along the way, he asks questions that the uninitiated may find odd for economics:

If seat belts save lives of crash victims, can mandatory seat belt laws, nevertheless, kill more people than they save?

Who benefits more from a legal ban on polygamy—men or women? What does the answer tell us about automobile manufacturers?

Why do movie theaters charge high prices for popcorn? If you think it’s because the owner has a monopoly once you enter the theater, then explain why he doesn’t charge for using the restrooms, over which his monopoly is even more secure.

Low prices and long ticket lines reduce the box office take for pop stars and alter the demographics of the audience; how does this relate to t-shirts?

How can each of two grocery stores claim (correctly) that the other store’s prices are 5% higher than its own?

Under what conditions is a higher rate of illiteracy desirable?

How do farmers in Iowa grow a crop of automobiles?

Why do stores charge $2.99 rather than $3.00? Hint: it has nothing to do with psychology.

Above all, Landsburg presents economics as a framework for intellectual discipline, consistency, and honesty. The book is not perfect; Landsburg admits coming from a particular point of view and, some argue, bypasses the holes in that point of view. But he does give readers the tools with which to challenge him. And in one small book, he answers the question, “What do economists do, and how do they do it?” and does so with style.

By the way, Landsburg’s two-sentence description of economics is a play on a Talmudic story about Rabbi Hillel (?-10 C.E.), who was asked to explain the whole of the Torah while the questioner stood on one foot. His response, which anticipated Christianity’s Golden Rule, was:

“That which is hateful unto you, do not do to your neighbor. This is the whole of the Torah; the rest is commentary. Go forth and study.”

HIDDEN ORDER (DAVID FRIEDMAN)

Like Landsburg, Friedman begins with his own definition of economics:

“Economics is that way of understanding behavior that starts from the assumption that individuals have objectives and tend to choose the correct ways to achieve them.”

Hidden Order often reads a lot like The Armchair Economist. Both have a strong free-market point-of-view. (Friedman’s father was Milton Friedman, perhaps the world’s best-known free-market economist.) They share many specifics—movie popcorn, cars growing in Iowa, polygamy. The similarity is understandable; Landsburg and Friedman are friends and strongly influence one another. When I was writing my piece decades ago, I sent separate emails to Landsburg and Friedman, asking each whether he could recommend any books similar in spirit to his own. To my amusement, Landsburg recommended Friedman’s book, and Friedman recommended Landsburg’s book.

Friedman’s book, however, picks up where Landsburg’s leaves off. The Armchair Economist is a grab bag of essays that can be read in any order; Hidden Order is structured—a book that should be read from start to finish. The Armchair Economist bounces between both micro- and macroeconomics; Hidden Order mostly sticks to micro. Landsburg uses an in-your-face style that takes no prisoners; Friedman is equally sure in his assertions, but employs kinder, gentler prose. Landsburg uses no equations or diagrams; Friedman uses a few. Landsburg imparts mainly the intuition of economics; Friedman develops the tools of the trade—the various curves and methods that one might find in an introductory economics textbook.

In the first hundred or so pages of Hidden Order, Friedman gives the novice at least a glimpse of the Promised Land of general equilibrium theory—quite a feat. Then, he launches into the theory of the firm, the time value of money, risk and uncertainty, efficiency, crime, love and marriage, politics, and the Rotten Kid Theorem. In short, he covers most of microeconomics.

Friedman peppers his book with references to Star Trek, ancient Viking/Irish military strategy, J.R.R. Tolkien, and folk song lyrics. He offers a theory on why it made good sense for British soldiers during the American Revolution to wear red uniforms and march in geometric patterns—practices often ridiculed in history textbooks of our era. Finally, he even tosses in a couple of pretty good economics jokes, such as:

“Two men encountered a hungry bear. One turned to run. ‘It’s hopeless,’ the other told him, ‘you can’t outrun a bear.’ ‘No,’ he replied. ‘But I might be able to outrun you.’”

Friedman’s book presents so much material so clearly in such a small amount of space that, especially for non-economics majors, it can stand by itself as an introductory textbook. In fact, Hidden Order is a stripped-down version of Friedman’s Price Theory: An Inermediate Text. The book didn’t sell well, so Friedman posted it on the Web as a PDF. Click the link, and you can read it online or download it free-of-charge.

ECONOMICS IN ONE LESSON (HENRY HAZLITT)

The last of the books reviewed here was the first written (in 1946). Since then, economists have established new domains for their science and have learned a great deal more about its older domains. So, Hazlitt’s long-ago work does not illustrate the full panorama of economics today.

That said, Economics in One Lesson makes a splendid dessert to Landsburg’s ause bouche and Friedman’s entrée. If the book were a star, it would be a white dwarf—tiny, hot, bright, and squeezing an awful lot of matter into a small space. As old as the book is, it is still a masterpiece of crystalline thought explained in a fine journalist’s prose. Like Landsburg and Friedman, Hazlitt began his book by reducing the whole of economics to a brief passage:

“The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.”

Hazlitt goes from one fallacy to another, shattering them as he goes. If nothing else, it would be helpful for every economics teacher and student to read Hazlitt’s Chapter 2 (“The Broken Window”). Borrowing from a parable spun by the 19th century economist Frédéric Bastiat, Hazlitt lays bare an economic fallacy ever-present in news accounts—a fallacy that oozes its way into common conversation, into the press, and into the worst excesses of public policy.

ADDITIONAL READINGS

For densely concentrated insight and pleasure, one can do no better than two classic essays by Frédéric Bastiat. Read these and wonder no more why my I chose to pay homage to Bastiat in naming this substack “Bastiat’s Window.”

“That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Not Seen.” Written in 1850, it remains a remarkably timely document for readers in 2024. Beginning with the aforementioned Broken Window parable, it also addresses issues of national defense, government funding of the arts, public works programs, the impact of public debt on wealth, taxation, replacement of labor by machinery, the rise of socialism, industrial policy, and more.

“The Candlemakers’ Petition.” This piece describes a hypothetical lobbying effort by candle manufacturers, who are requesting that the government erect contrivances to block the sun’s light in order to ramp up employment and production in the candlemaking industry. This logic is not much different from contemporary calls to enact tariffs and quotas to boost domestic production and employment.

Finally, here are a few additional books that do a good job of explaining the logic of economics, along with some interesting findings. I’m not sure what it says about economists or about people who read books by economists, but I notice that all the authors allude to sex in their titles or in their subject matter.

Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything (Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner;

Discover Your Inner Economist: Use Incentives to Fall in Love, Survive Your Next Meeting, and Motivate Your Dentist (Tyler Cowen);

Naked Economics: Undressing the Dismal Science (Charles Wheelan)

Sex, Drugs & Economics: An Unconventional Introduction to Economics (Diane Coyle)

More Sex Is Safer Sex: The Unconventional Wisdom of Economics (Steven Landsburg)

“BUELLER, BUELLER, BUELLER …”

The video above shows what may be the most famous economics lecture of all time, with Ben Stein playing the world’s dullest econ teacher. The scene is from the 1986 comedy, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. In real life, Ben Stein is a talented and insightful economist/attorney/journalist—and a colorful lecturer, to boot. His father, Herb Stein, was chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under Presidents Nixon and Ford. In 1968, Herb Stein became the founding president of the National Economics Club (NEC) in Washington, DC. In 2012, I was NEC’s president and invited Ben Stein to deliver a lecture in memory of his father. Below is a photo from the event, held at the Canadian Embassy; Ben and I are in upper left-hand corner—him in the blue shirt and me in the white. The bagpiper was there to honor Adam Smith—the Scotsman whose The Wealth of Nations (1776) is considered the founding document of modern economics.

Have you seen the video showing a debate between Keynes and Hayek using a rap format? As a student of economics whose readings have included (among many others) “Human Action” by Ludwig von Mises), I found this video to be both entertaining and affirming.

What about Dr. Sowell's Basic Economics?