If you’re not already a subscriber to Bastiat’s Window, please sign up for a free or paid subscription. (Paid really helps!) By all means, share the site and its articles with friends.

Last month, my friend Tom Humphrey died. This collection of remembrances is written equally for two audiences—those who knew Tom, and those who didn’t. Once in a while, a true original passes by. This a chance to say hello and bid farewell to one of them.

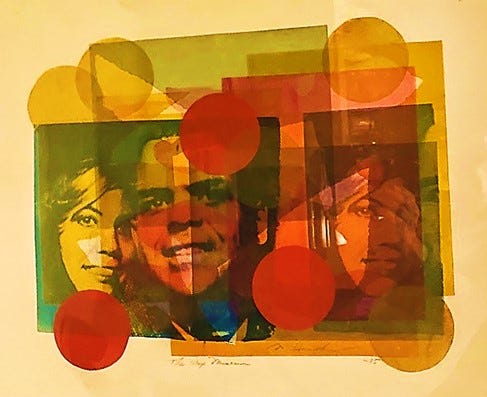

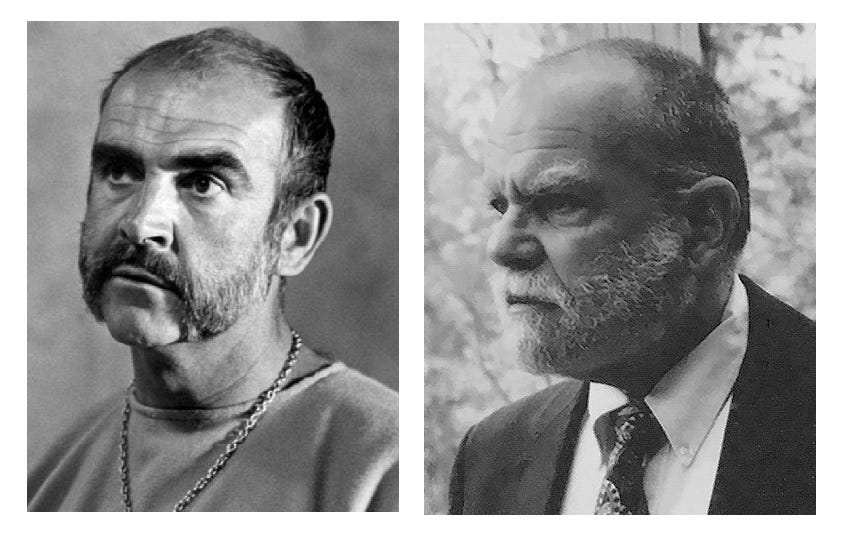

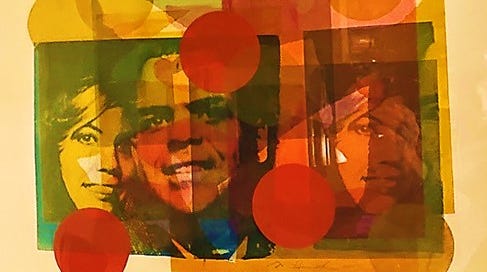

Tom was both Renaissance Man and Tennessee Mountain Rustic, straight out of central casting. He was an economist within whose mind swirled centuries of history—the impossibly detailed intricacies of money, banking, and scientific doctrine. In the years I worked with Tom at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, ours was a formal workplace in a formal town, where one wore conservative suits, even on the torrid, sweltering days of summer, when the short walk from office to automobile left you and your business attire drenched in sweat. The building itself was sleek and modern, as were the furnishings. The one exception to all this was Tom Humphrey’s office, where this wanderer through the centuries sat most of the day in a beat-up wood-and-wicker rocking chair, scribbling intensely on pads of paper, rocking all the while. The blue-suited denizens who came to call found a proud Scotsman from Eastern Tennessee, clad in rumpled pants, a checkered work shirt, fearsome eyebrows, and a tangled gray beard and mustache. In outward appearance and outsized personality, he reminded me of Sean Connery’s Daniel Dravot in The Man Who Would Be King (1975). Here they both are, so you decide whether I’m onto something.

When this essay began to take shape in my mind, one word kept coming to me—”eccentric.” I wondered whether that word might hurt the feelings of Tom’s wife, Mitzi—also a dear friend since I met Tom in 1988 or 89. Then, I read his obituary, which I presume she had a hand in writing:

He was by turns solitary and sociable, gruff then good natured, eccentric but easygoing, sardonic and sweet, brusque and brilliant, sharp and sentimental, laconic and loving—a true idiosyncratic individual and old-school ‘absent-minded professor’—full of character, contradictions and humanity. There will likely never be another Tommy Humphrey, not in our lifetimes anyway, and we who remain in this realm are richer for knowing him.

I was relieved to see, the “e-word” was acceptable. In three-and-a-half decades of friendship, the one thing I never knew was how much of Tom’s eccentricity was natural and how much was purposefully, meticulously curated. He clearly knew his image and reveled in it. As did all of us who shared the gift of his friendship.

What follows below are a few stories and remembrances to give a fuller image of the man. I’m pleased to be assisted in this task by four of my erstwhile colleagues from the Richmond Fed—John Walter, Bob Hetzel, Dave Mengle, and Al Broaddus. All of us were economists there, and Al served as president.

Tom was the longtime editor of the Fed’s scholarly journals, and he hired me in 1989 to be his managing editor; our collaboration was one of the highlights of my career. Tom encouraged me to write unconventional works, including one on what Europe might expect if it adopted a common currency (i.e., the Euro) and one that became my first work as a health economist. Tom and I co-authored one wonky, arcane paper on historical thought in monetary policy.

Below, Bob Hetzel describes Tom as “a giant in the history of economic thought.” I’d add that, perhaps because Tom was a modest man, not prone to self-aggrandizement, his impact exceeds his fame. Tom’s writings have enabled the sweep of history to offer stern advice to the Federal Reserve and to central banks everywhere. Whether or not those in charge know it, whenever the Fed acts with restraint and wisdom, its policymakers owe a debt of gratitude to Tom’s lifelong toil. And whenever the Fed tosses restraint and wisdom to the wind, those in charge need to go off to quiet places, sit in rocking chairs, and read the lessons that history whispered in Tom’s ears.

Clothes Make the Man

Tom Humphrey’s Rustic Mountain Man™ image contrasted sharply with that of his wife of 66 years—Mitzi Greene Humphrey. Mitzi is also from Tennessee, but she is an urbane, always elegantly attired avant-garde artist. Their mutual devotion was as deep as any I’ve ever known. Observing their differences made knowing them all the more enjoyable. Tom once told me of an occasion on which their aesthetic sensibilities clashed, with disastrous results.

On a car trip from Richmond to Tennessee, Tom had agreed to stop halfway, in the little mountain town of Wytheville, Virginia, to give a lecture at the local community college. Tom generally didn’t bother to prepare his lectures till an hour or two beforehand, and this trip was no different. He planned to find a diner in Wytheville and spend an hour or two figuring what he would talk about. As they pulled into town, in full absent-minded professor mode, Tom realized that he had forgotten to pack a suit for his lecture. No matter, he told Mitzi, I’ll just go as is. The elegant Mitzi said, “There’s no way you’re going to represent the Federal Reserve dressed that way. You’re going to go buy a suit.” Tom protested that he didn’t know where to buy a suit and that he needed time to prepare his lecture. “You’ll get a suit first,” Mitzi said, with stern authority and no higher court of appeal.

In this long-pre-GPS era, they managed to find a men’s store and get Tom fitted with a suit. By the time they walked out of the store, it was nearly time for the lecture, and Tom had no idea what he was going to talk about. So, he strode to the front of a packed classroom and gave a lecture that, from Tom’s description sounded something like this:

“Back in 1734, the money supply, uuuh, but later, Adam Smith wrote … uhh … in 1913, Knut Wicksell, … no, let me first mention what Walter Bagehot said in 1873 … but the real bills doctrine was … OK, the problem today is the dual mission that Congress has given the Fed … deflation … did I mention the Scottish free-banking epoch? … which you may know wasn’t at all like the so-called ‘free-banking’ experience in Mississippi, … [etc. etc.]”

Tom said it was absolutely the worst, most disorganized, incoherent lecture of his entire career. At the end, he asked the audience, “Are there any questions?” In return, he got dead silence and blank stares. Even the metaphorical crickets declined to chirp. As if lifted by an unseen force, every single person in the room rose in perfect synchronicity, turned around, and headed out the door—with one exception. When all others had filed out and disappeared, one elderly lady remained seated in the back of the room. Tom thought, “Thank goodness. … At least I reached one person in the audience.”

The lady got up from her seat, ambled toward the front of the room, and approached Tom. After a few long moments of silence, she asked, “Young man—did you know that you still have a label on the sleeve of your jacket?”

The Patience of Job (by John Walter)

Tom Humphrey greeted me with a welcoming smile whenever I stopped by his office. Somehow, the fact that he sat in a well-worn cane rocker with a writing board across the arms added to his approachability. When I was a probably-annoying, certainly-opinionated, but ignorant, underling, he spent many an hour patiently discussing questions of economics and life.

Tom had the forbearance of Job when editing papers I submitted for publication. I am embarrassed to think how many hours he must have spent editing each of my papers. I can remember a multitude of cases in which Tom offered a revision that converted a long and convoluted paragraph into one short sentence that exactly conveyed my meaning. He surely understood my idea better than I did, and knew exactly how most transparently to convey that idea to the audience.

Of course, Tom’s training in and love for economic history played a prominent role in my memories of his participation in Research meetings. I was amazed by his ability, at the drop of a hat, to link almost any cutting edge economic prognostication back to a similar view espoused by some 18th- or 19th-century economist. This input often helped round out the logic of the discussions, but also, I think, kept the discussion somewhat humble—as in, “we are certainly not the first to come up with this idea.”

Man on the Run

Tom was the single most obsessive runner I’ve ever known. In the years I knew him, Tom was always rail-thin and sinewy. As our colleague John Walter said:

“Tom was a beast about running. He never missed a day pounding the pavement even when sick or injured. I remember one time when he continued even when suffering from a stress fracture—in his foot I think. He claimed that he ran so that he could ‘eat what he wanted,’ without guilt. And Tom certainly seemed to enjoy our cafeteria lunchtimes without guilt—even though they often involved heated debates with our colleague, Tim Cook.”

Tom was the most prominent, most devoted member of what amounted to a runner’s cult at the Richmond Fed. Some days, he and the others would spend the entire lunchtime sharing with the rest of us the gruesome inventories of their fractures, breaks, torn ligaments, damaged muscles, and surgeries. One cold wintry day, I walked into Tom’s office, finding him in shorts, t-shirt, and tennis shoes, drenched from rain and sleet and toweling off before changing back into his work wear. He warned me not to come into his office. “Why not?” I asked. He said he had the flu and was running a 102° fever.

Tom’s devotion to athletics went far back. He played baseball at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where he met, courted, and married Mitzi. He briefly pitched semi-pro baseball for the Knoxville Smokies (now Tennessee Smokies). As John Walter suggested, Tom did run so that he could eat Diamond Jim Brady-sized lunches without adding an ounce to his frame, but that was not his only motive. In his youth, Tom had suffered from polio. He had emerged victorious and seemed determined to thumb his nose at the microbe every day for the rest of his life.

Clothes Make the Man, Part II

If you sense that Tom’s attire was a key part of his image, you are correct. These days, it’s difficult to recall just how rigid dress guidelines were in the workplace a few decades back and how pleasantly jolting Tom’s defiance of convention was. He was never sloppy—just different. And he could clean up with the best of them when the occasion called. You can see that in the Connery-esque photo above. Mitzi shared with me the above two portraits, showing that he was familiar with formal garb and neckwear from an early age. On the left is a childhood portrait, painted by his grandmother, Eleanor Belknap Humphrey. On the right is a photo of an impossibly dashing young Tom on his wedding day in 1957.

One day, public relations folks at the Richmond Fed decided to clean their files and discarded a large collection of old photographs, leaving them on a table for anyone who wanted them. I sifted through the collection and found a decades-old photo of Tom with two striking characteristics—he was overweight and was wearing a suit. I strolled into his office and held it up to his eyes. He grinned broadly.

I said, “I’m guessing this was before you began running,” and he nodded. Then I said, “I can also tell exactly when this was taken by the suit. Those lapels are a mile wide. No one has worn anything like that since the 1970s.” His grin got even bigger, and he popped up out of his chair and walked over to his door. In the next moments, I realized that Tom’s door was never closed when he had visitors and that I had never seen the back of it. He closed the door, and there hung That 70s Suit—the one with the mile-wide, Gerald-Ford-must-be-president lapels. This, he explained, was still his go-to suit on those occasions—rarer than a total eclipse of the sun—when he needed to look Fed-like. The shock of seeing him in a suit was apparently sufficient that I had never noticed the antediluvian specifics of the outfit.

There was no label on the sleeve. Nor do I know whether it was the same suit purchased on the fly in Wytheville.

Tom and the Sweep of History (by Bob Hetzel)

Tom was a giant in the history of economic thought. Almost alone, his papers chronicled the history of the quantity theory of money. That makes him indispensable to an understanding of central banking today and to the design of an optimal monetary standard—a matter of existential importance. The Federal Reserve has always struggled to implement a standard that provides a stable framework for a market economy. To answer the question of how to design a stabilizing monetary policy, one must start with an answer to the question of whether the price level is a nonmonetary or monetary phenomenon.

Resolution of the issue of the nature of the price level—nonmonetary or monetary—has always bedeviled the economics profession. Different schools of thought (e.g., Keynesian and quantity theory) construct models based on different assumptions. The issue is how to test the models. A judicious and selective choice of data can seem to validate any model. Genuine empirical verification of the validity of competing models requires organizing historical experience as a series of semi-controlled experiments capable of offering information on causation. What is the causal order? Are prices determined and money follows, or is money determined and prices follow? Because the “experiments” are not the outcome of a randomized, controlled laboratory experiment, empirical verification requires generalization from a concatenation of the experiments offered by history.

Here is where Tom’s enduring legacy enters. Tom documented two centuries of these experiments. His scholarship allows identification of a consistent pattern. The price level is a monetary phenomenon. A central bank is not a master puppeteer pulling strings to control the real economy while producing an acceptable amount of inflation. A stable monetary standard requires that the control bank follow a rule that makes money creation consistent with price stability and allows the price system free rein to determine employment and output.

Tom’s output was prodigious. Much of it resides on the website of the Richmond Fed. More can be found spread around the internet.

The Land of Enchantment

In 1992, I traveled with my wife and son (Alanna and Jeremy) on our first trip to the American West—to New Mexico, specifically. New Mexico is a supremely quirky place, and Tom was mesmerized by my stories. When he and Mitzi decided to visit in 1993, Tom asked me to plan their itinerary step-by-step.

To his delight, Tom found that New Mexico was a state filled with people more off-the-beaten-track than he. At some point, he and Mitzi were searching for Ghost Ranch, the Abiquiu home of artist Georgia O’Keefe, but they couldn’t find it. After circling the primordial landscape for a while, Tom spied some rustic geezer sitting on the porch of an old house. Tom walked up to the house and asked, “Excuse me, but we’re looking for Ghost Ranch, the home of the artist Georgia O’Keefe. Would you happen to know where that is?”

The guy said, “Sure, I know where that is. I can show you how to get there.” He went inside his house and returned with two big plat books—official town or county property records. He showed Tom how to get there. Tom told him thanks, and then asked, “Do you mind my asking why you happen to have plat books in your house?” The guy answered, “Cause I’m the mayor.” This was Tom’s kind of place.

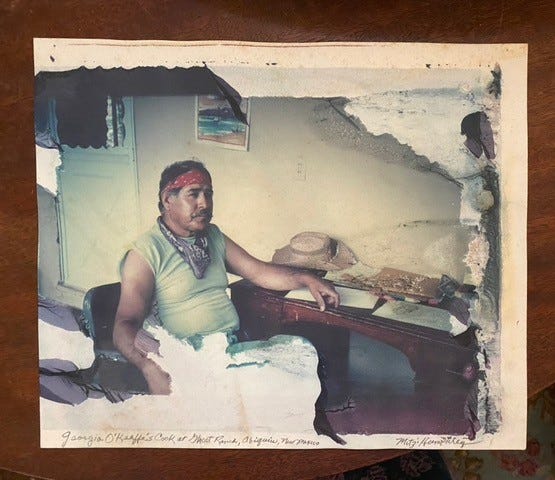

Ghost Ranch was not open to the public in those days, but Tom and Mitzi found the caretaker to the property, who was also O’Keefe’s cook. He let Mitzi take some behind-the-fence photos of the house. He said O’Keefe was always firing and re-hiring him. Mitzi told me that O’Keefe was known to love good, fresh food, and that this fellow must have been an excellent cook.

Herder of Cats (by Dave Mengle)

It was Spring of 1984—the first sweltering day since my arrival in Richmond. I was walking near Downtown in the then-prevailing Fed economist uniform of a blue blazer, button-down shirt, tie, and khakis. In the distance, I saw what appeared to be a homeless man jogging toward me. My first impulse was to cross to the other side of the street. But as the shirtless man got closer, I figured that “homeless” and “jogger” typically don’t describe the same person, so I stayed the course. Whoever he was, he resembled either Willie Nelson without the braids or Neptune without the trident. Finally, I realized it was Tom, and as I greeted him, he passed me by, staring straight ahead, oblivious of my existence. Later that day, I dropped by his office to mention having seen him, and there were his shorts and socks, drying on one of his chairs; I’m convinced this was his tactful way of discouraging visitors so he could get some work done without interruption.

Tom wasn’t the kind of guy you could sum up in one or two anecdotes. On the contrary, it was conversations—while running, during lunch in the cafeteria, in his office, ranging from his stint in the Army, his time in semi-pro baseball, his teaching at some small Southern colleges, and, yes, about economics and economists—that formed a picture of an intensely interesting and entertaining man.

Having read this far, you’ve doubtless noticed the e-word—eccentricity—recurring in the remembrances above. Anyone who’s worked in a research department in any firm would know, however, that research departments tend to attract eccentrics, and the Richmond Fed was no exception. Managing researchers is a difficult task: think of the expression “herding cats,” or imagine an army unit made up of nothing but generals, and you’ll get the idea. Tom didn’t run the Research Department—he would have recoiled from administrative tasks like a vampire recoils from garlic—but he was the editor of our scholarly journal, the Economic Review, which involved similar challenges.

Here is where Tom made a lasting impression. Most of us arrived as freshly-minted econ PhDs from the grad school assembly line. Each of us was convinced that we had novel, unique insights to share with the world and that every word we wrote was important. It fell to Tom to rein in our youthful exuberance. As John Walter wrote above, he must have spent hours trying to edit our work. His comments could be incisive, sometimes biting, but they were never patronizing or insulting. Once, I was asked to contribute an article to the Annual Report on the evolution of banking in the Richmond Federal Reserve District. I obliged with a twenty-something-page summary of the gradual consolidation of hundreds of local banks into a few giants in each state and the ongoing consolidation into interstate behemoths. That required extensive research, and I was obscenely proud of the result. Tom and another senior officer read though it and agreed that, brilliant as it was, it needed to be shrunk down to about six or so double-spaced pages. I was horrified and insulted, but reluctantly agreed to do some editing, first to about fifteen pages, then to ten, and finally down to six. At the end, we ended up with an altogether superior and even readable product. That made an impression on me, and I look upon that experience as a step toward adulthood, which doesn’t always come easily among us research guys.

Rest in peace, old friend.

Memories of Tom Humphrey (by Al Broaddus)

Tom Humphrey was my colleague in the research department at the Richmond Fed for close to 35 years. And he, my wife Margaret and I were members together of a small running group and the social group that grew up around it, which extended our friendship to a little over a half-century. When I used to attend economic conferences and my name tag linked me with the Richmond Fed, frequently other attendees would immediately note that Tom Humphrey worked there.

Knowing Tom was one of the great pleasures of my life, professional and otherwise. His Richmond Fed résumé is long and distinguished: the extraordinary bibliography of his own professional papers, to be sure, and his exceptional (and often arduous) work editing articles drafted by his associates for our Economic Review and other publications. A contribution especially dear to my heart were Tom’s memos at pre-Federal Open Market Committee meetings, where he would comment on whatever points we were considering making in Washington from the perspective of the timeless classical literature on monetary economics–like putting a frame on a picture. But for me Tom’s most important contribution to our department was the constant reminder provided by his presence among us that we were economists—part of a regularly criticized and sometimes ridiculed, but nonetheless essential profession with a distinguished intellectual history, laboring to make sense of a critically important dimension of human activity. As in other, similar workplaces, routine daily work in our department could become frustrating at times, but it was difficult for me or any of our department colleagues to lose our motivation with Tom down the hall rocking in his rocking chair and writing about David Ricardo, Henry Thornton, Knut Wicksell or whoever’s ideas he was reminding us of on a given day.

As for running and socializing with Tom, like working with him at the Fed, he was one of the most remarkable people I’ve ever known, friends I’ve ever had, or teachers I’ve ever had about human nature and its variety. Our running group, now diminished, still recites a collection of (for us) memorable stories of our history together; the portion of that collection focused on Tom is substantial. While we sometimes poke fun at Tom’s running eccentricities, he was an accomplished runner who completed some of the country’s most prominent marathons in respectable times.

All of us who worked, ran, and otherwise spent quality time with Tom are missing him very much.

LAGNIAPPE

An Eye Made Quiet

In 2022, I wrote “Stones of Antiquity,” a three-movement choral suite that is perhaps the most peaceful, naturalistic work I’ve ever composed. The recording is here, accompanied by paintings by my wife, Alanna, who has also been a friend to Tom and Mitzi Humphrey.

By fortuitous chance, the themes of the pieces were Scotland, the Appalachians, the Scottish diaspora in America, history, and New Mexico—all subjects associated with Tom. After 88 years on this earth, he himself now rests amid the stones of antiquity, and those of us who knew him are all the better for the good fortune of his long, yet all-too-brief visit. Ever the Scotsman, Tom always took the high road.

Listen to this music with headphones to hear the choir resonate across the moors and the mountaintops—from the Isle of Skye to the Rio Grande. As the music plays, read the quotes by William Wordsworth, John Muir, and Andy Goldsworthy—all of which could have been written with Tom Humphrey in mind. He wasn’t in my thoughts when I composed this suite, but in hindsight, it seems obvious to dedicate this work now and forevermore to the memory of Thomas MacGillivray Humphrey.

I like to think that somewhere out in the firmament, Tom can finally offer his insights to an attentive audience of Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Knut Wicksell, and the rest of the economics pantheon—to the amusement and edification of all his esteemed listeners. As his obituary concluded:

Rest easy now, Tom.

Your race is run, you finished strong.

Godspeed you home.

We love you and miss you, until we meet again.

I guess your music is the finale of my day. I lack sufficient adjectives. My family roots are in the Waxhaws from the time of the revolution. Before that Scotland (most likely exiled to Ireland first).

A friend from Las Cruces was an excellent cook of Mexican food. He was also a marathon runner and one pre-race meal with him (the amount prepared and consumed) resulted in my vow to give marathon eating a try.....and the necessary running to subsidize it.

I am running way behind today. I once ran marathons, primarily so that I could eat what I wished and in whatever quantity I desired. Today it is because I read slowly. This wasn't the only truly moving piece I came across, but it rained so it was a day to reflect and rest. I knew nothing of Tom, but now I add another admired character to my list. You and Tom's mutual friends have done him a great service.

I thank all of you for enriching my life. Now on to your music. I once composed and recorded, but while I felt great enjoyment at the time, it was all truly slightly below average.