[1] HE DID. BOOM.

My friend, Nina, told me long ago of a party she attended at the home of Marina von Neumann Whitman, then Chief Economist for General Motors:

A guest spoke with Whitman’s young daughter and then told Whitman, “She was talking so sweetly about her grandfather, and I asked what he did. She told me, ‘He invented the computer,’ and I thought that was so cute of her to say.” Whitman looked at the guest, whom she apparently didn’t know, and said, “He did.”

The grandfather was John von Neumann, one of the 20th Century’s most penetrating minds. He was instrumental in creating or advancing digital computing, quantum theory, game theory, automata theory (e.g., DNA replication), defense planning, the Manhattan Project, meteorology, and countless fields of pure and applied mathematics. Nina told me this week that Whitman spoke sometimes of the “sibling rivalry” between herself and the computer.

My favorite von Neumann story relates to relativity, originated by his colleague, Albert Einstein. von Neumann had a reputation as an incautious driver. Once, he plowed his car into a tree and supposedly told the police:

“I was proceeding down the road. The trees on the right were passing me in orderly fashion at 60 miles per hour. Suddenly, one of them stepped out in my path. Boom!”

[2] TING, TING, TING!

Six decades after von Neumann “invented the computer,” Apple harnessed his principles to create the iPhone. At its 2007 rollout, Steve Jobs said:

“Every once in a while, a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.”

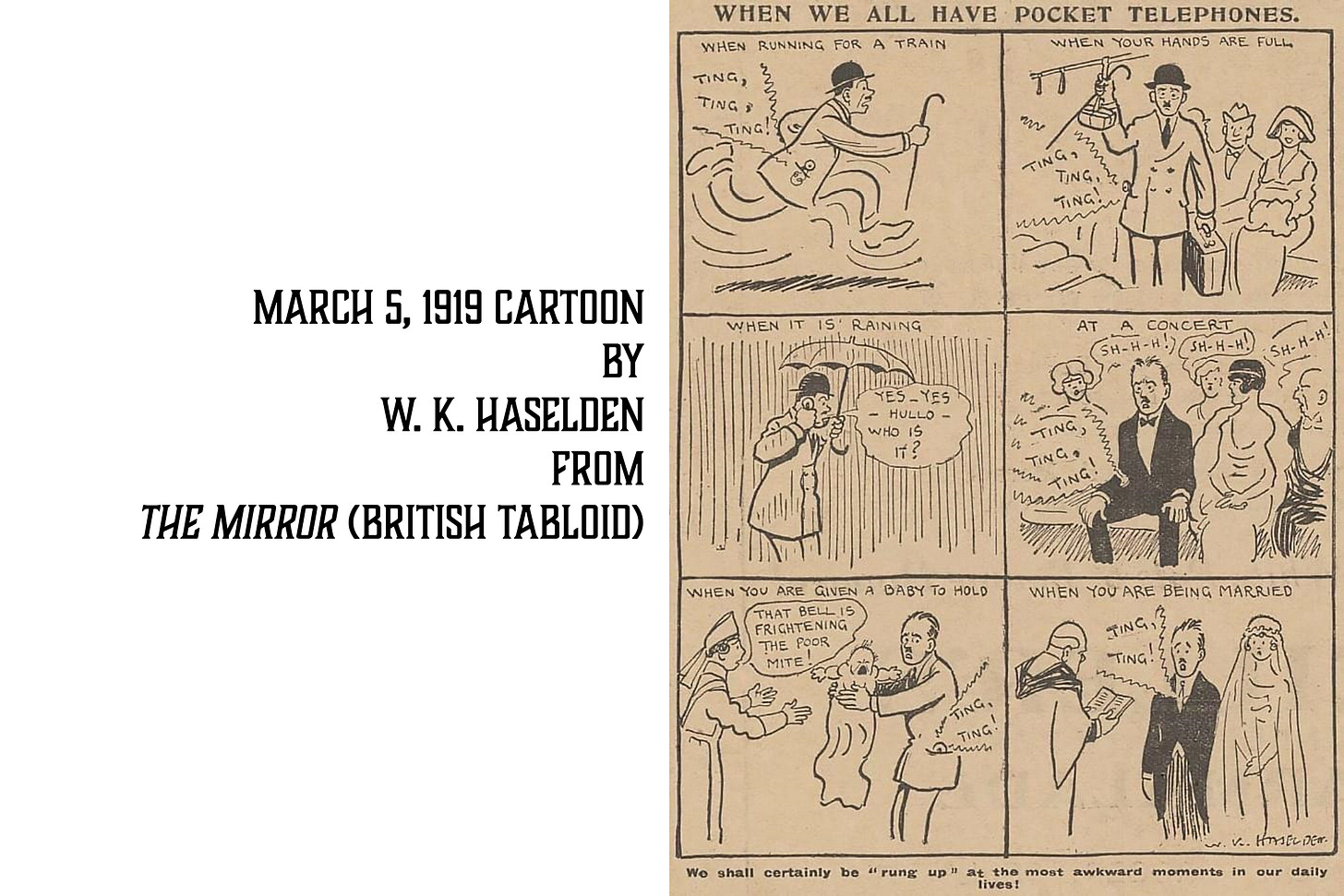

Such boasts are common among entrepreneurs, but in this rare case, the hyperbole proved accurate. Among other things, smartphones and related devices: (1) universalized the annoyances foreseen in W.K. Haselden’s 1919 cartoon pictured above (“When We All Have Pocket Telephones”) (2) fostered an epidemic of mental illness among young people; (3) enabled the world to survive isolation during COVID; (4) destabilized governments; and (5) provided the means to establish lifesaving global communities.

[3] REWIRING KIDS.

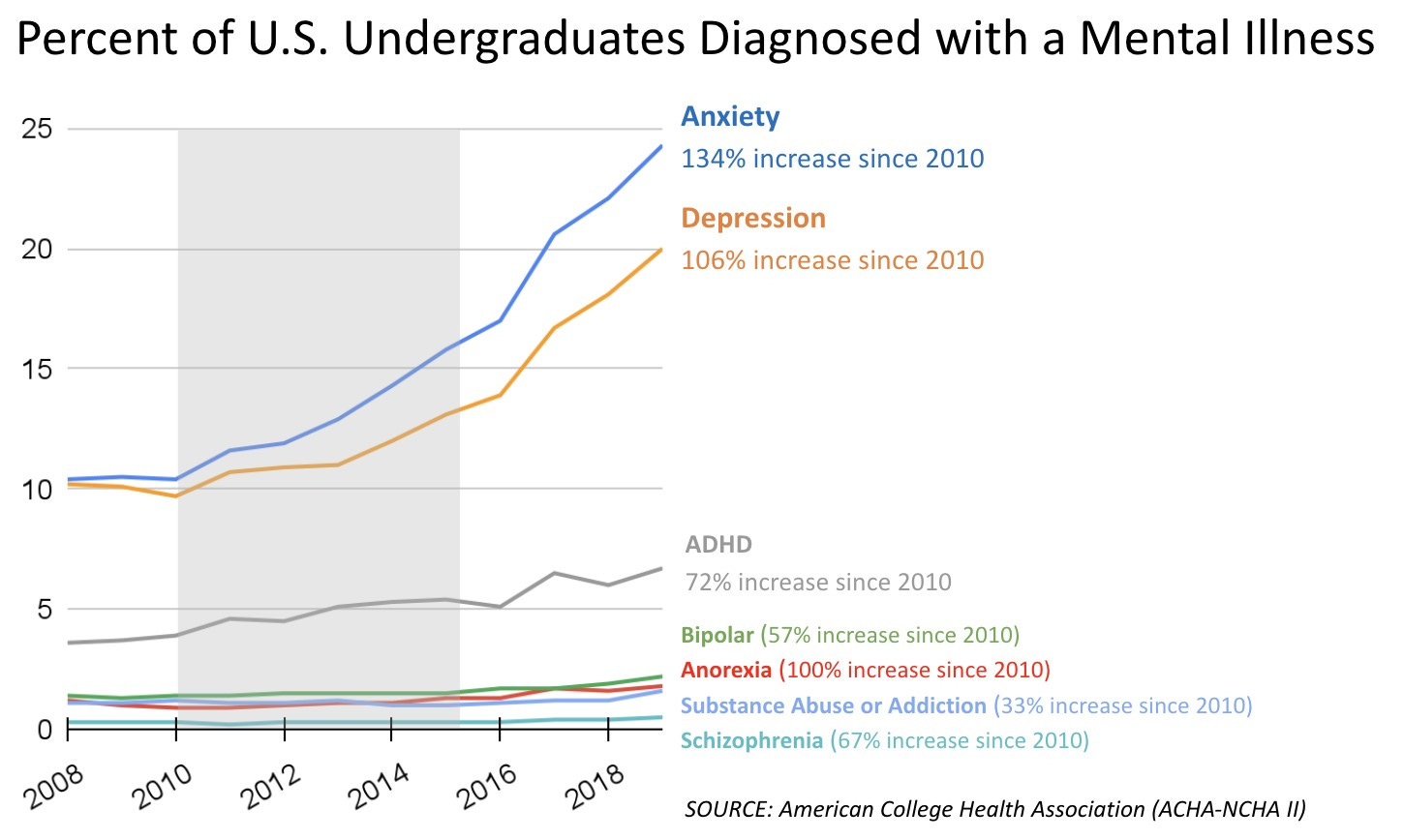

Jonathan Haidt’s 2024 book, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness argues that overuse of and addiction to cellphone usage has shattered social connections and induced a rapid, dramatic rise in depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide across Generation Z.

My wife, Alanna, worked from 2000 to 2015 as a high school librarian, technologist, and instructor of research methods. In the 2010s, she sensed an unsettling change in her students. The fun was draining out of her work, and she chose to retire. She doesn’t agree with all of Haidt’s assertions but said his overall thesis jibes with what she had sensed—crystallized in a graph Haidt shares:

Haidt, no technophobe, offers a draconian solution in “The Case for Phone-Free Schools. Incidentally, Alanna is a technophile whose task at both schools was designing and overseeing the construction of 21st century, highly interconnected libraries—facilities designed for students with laptops, tablets, and cellphones. Previously, she had performed similar tasks for a large public library system, a Fortune 500 company, and Columbia University.

[4] THE MACHINE STOPS

The following incorporates some passages from my “The Machine Starts: Ideology of the Timid,” published by InsideSources in 2021.

A decade before Haselden’s cartoon, British novelist E.M. Forster produced a starkly prophetic vision of connectivity and COVID-like lockdowns. In his novella, The Machine Stops, people live in one-person underground cells where life consists of videoconferencing, Zoom-like lectures, streaming music, telemedicine, and memes masquerading as ideas. They despise travel, physical experience, and human contact—preferring their sterile, solitary chambers and communication via glowing screens. They are equally disgusted by the idea that someone else might desire a more robust, physical, inquisitive, interpersonal life.

We see hints of this inward-looking impulse today. Richard Branson’s Virgin Media, Jeff Bezos’ Amazon, and Elon Musk’s PayPal helped make isolation tolerable during the pandemic, and all three harnessed their earnings in pursuit of space travel by both professional astronauts and amateurs. Today, passive, isolated trolls who have substituted social media for social life hurl opprobrium at these “billionaire rocketeers” whose lucre would presumably be better spent on those posting cat videos on TikTok, meals on Instagram, memes on Facebook, and insults on X/Twitter.

[5] CRAB-BUCKET POLITICS

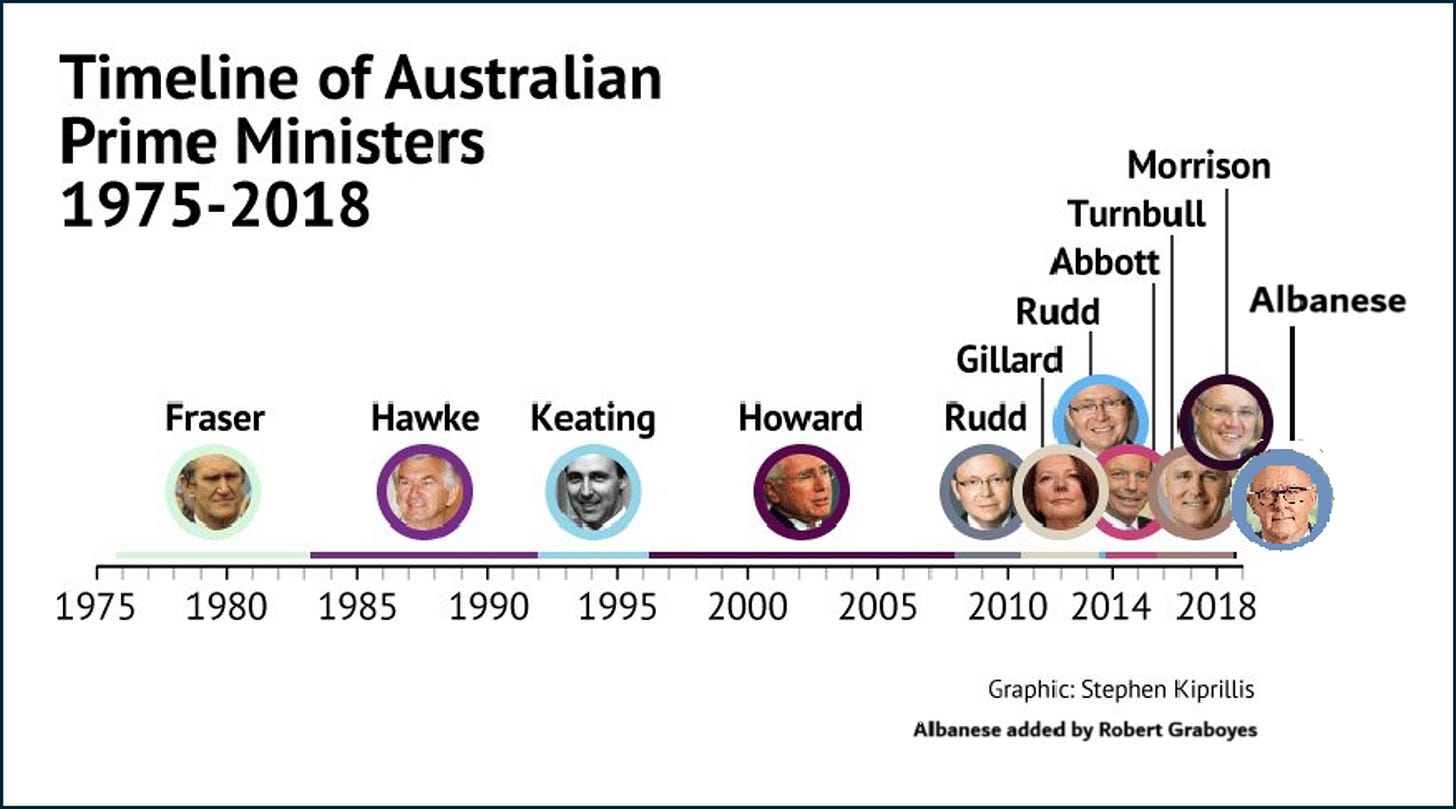

In 2018, the Sydney Morning Herald noted:

“Between 1975 and 2007, Australia had four prime ministers. In the 11 years between 2007 and 2018, we've swapped six times.”

I’ve updated the graphic to show that since 2007, they’ve swapped prime ministers seven times. Beginning with 1976, the numbers are identical in the UK. This pattern—seen in numerous countries—began immediately after the introduction of Twitter and the iPhone.

[6] WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT?

A spark of divinity resides in the idea of connectivity. An ancient “internet” existed at the start of the Jewish exile in Babylonia (587 BCE and afterward). Lines of mountaintop signal fires enabled Jewish priests to almost instantaneously inform exiles hundreds of miles away that a new moon had been sighted at the Temple in Jerusalem—thus marking the start of a new month. (Read the accounts of Lachish and Azekah.) In 1844, Samuel F. B. Morse initiated the first long-distance telegraph message (Washington to Baltimore) with the Biblical phrase, “What hath God wrought?”—fitting, given since Morse believed God was working through him to offer mankind a new tool.

[7] MESOPOTAMIAN MEDICINE

In ancient times, the Fertile Crescent saw another parallel with today’s Internet—medical crowdsharing. The Greek historian Herodotus (c .484—c. 425 BCE) described Mesopotamian medicine:

The following custom seems to me the wisest of their institutions. . . . They have no physicians, but when a man is ill, they lay him in the public square, and the passers-by come up to him, and if they have ever had his disease themselves or have known anyone who has suffered from it, they give him advice, recommending him to do whatever they found good in their own case, or in the case known to them; and no one is allowed to pass the sick man in silence without asking him what his ailment is.

[8] 20TH CENTURY SIGNAL FIRES

Following is a snippet from my 2015 article, “Why We Need to Liberate America’s Health Care,” published by PBS:

I personally witnessed an incident that I like to think of as the moment of impact between 20th century medicine and 21st century information technology. In the spring of 1993, the Navajo and neighboring tribes in the Four Corners Region suffered an outbreak of hantavirus—a pulmonary illness spread via deer mouse droppings. Twenty-four people fell ill, and 12 died. Months later, a truckload of antique legal documents from the Navajo reservation arrived at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, to be stored in the bank’s vault until a federal court case some months later. An alert loading dock employee noted the shipment’s origin, saw some droppings, and remembered the news accounts.

A phone call quickly alerted the bank’s physician, Dr. Victor Brugh, to the possibility of a deadly virus circulating through the 24-story tower’s ventilation system. Brugh emailed the CDC. Questions flew, others joined the conversation, and in an hour or two, the CDC determined there was no danger to the thousands of employees.

It is virtually impossible for us today to internalize how remarkable this conventional-sounding story was on that day. The bank had only recently installed an email system, and the technology still seemed other-worldly. Brugh shook his head in disbelief at how rapidly he and others had resolved the potential crisis. Just a short time earlier, he told me, the incident would have meant hours or days of back-and-forth phone calls, busy signals, and missed connections.

[9] VON NEUMANN MEETS HERODOTUS

A generation after my friend, Nina, attended the party with John von Neumann’s daughter and granddaughter, the life of her husband, Arturo, was restored by the interconnected world that combined von Neumann’s architecture and the crowdsharing described by Herodotus. In turn, Arturo improved (and perhaps saved) the lives of strangers around the world using those same tools.

In 2005, Arturo suddenly collapsed from systemic capillary leak syndrome (a.k.a., Clarkson’s Disease)—a deadly condition involving episodic collapse of blood pressure. The disease is so rare that most doctors have never seen a case and would likely misdiagnose it if they did. Before 2005, patients like Arturo would almost never meet another patient who shared this illness. Writing in 2009 of his odyssey, the Washington Post said,

“It is possible, Arturo Porzecanski will tell you, to feel very lonely even when there are people all around you.”

Arturo discovered a website—RareShare—that connects patients with rare medical conditions. Working with RareShare, Arturo became instrumental in building a worldwide community of patients with Clarkson’s Disease and of practitioners knowledgeable in the illness. Building this community proved to be a life-saving improvement for Arturo and for other patients.

So, the same technologies that can shatter one’s sense of community can also create a sense of community that was never possible before. The technology changes everything, for better, for worse, or both. It’s all in how you use it.

[10] ANYONE

In Black Mirror’s episode, “Fifteen Million Merits,” people live alone in tiny, sterile, one-room cubes outfitted with video screens—much like Forster’s characters in The Machine Stops. In the above videoclip, cube-dweller, Abi (Jessica Brown Findlay), sings on a Britain’s Got Talent-type program. The “audience” before her consists of thousands of videogame-like avatars, each representing a cube-bound viewer.

I won’t tell more about the episode but will, segue over to the connectivity-soaked history of Abi’s song: “Anyone Who Knows What Love Is (Will Understand).” First recorded in 1964 by Irma Thomas—the “Soul Queen of New Orleans,” the song and singer were only modestly successful back then. When the Black Mirror episode aired, songwriter Randy Newman was watching and thought the song sounded vaguely familiar—and for good reason. In 1964, it was partially composed by 23-year Jeannie Seely—a secretary at Liberty Records. She struggled to finish it and asked a young songwriter for help. He was a 19-year-old Randy Newman, who went on to become a prolific songwriter. Seely veered into country music and has performed onstage at the Grand Ole Opry more than anyone else in the venue’s history (5,000+ times).

So, 47 years after the song’s modest debut, it finally became a hit, thanks to a television program about the dark side of connectivity—amplified by Netflix, YouTube, Spotify, social media, email, etc. It brought newfound attention to Seely, Newman, and the nearly-forgotten Thomas.

Think you should change the name f your blog to:

Bastiat's Restaurant---Delicious tidbits served!

This batch was marvelous!

The cartoon from 1919 is fantastic! I love it.

Some related thoughts:

In his novel THE DIRECTORATE, author Berthold Gambrel imagines a society that has collectively agreed to eschew mobile phones and social media for the greater good.

In 2005 I gave a speech on data storage tech trends at the hard disk drive industry’s annual year-end get-together. “Can you imagine,” I asked, “people happily watching ‘Lost’ or ‘Harry Potter’ on a tiny cell phone instead of a big screen? These things are just so many shiny objects that have temporarily captured the public’s imagination. And seriously, can you imagine a public so trusting and foolish that they would allow their personal data, photos and financial information to be stored in some imaginary cloud?”

I have since given up prognosticating.