The Self-Harm of Economic Populism

"Tax the Rich" and "Tariff China" are equivalently self-destructive nonsense

DON’T TAX YOU. DON’T TAX ME. TAX THAT FELLOW BEHIND THE TREE.

Democrats want to punish the rich with taxes, and Republicans want to punish China with tariffs. The two are analytically equivalent, and both bring to mind H.L. Mencken’s chestnut, “There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.” Maybe six weeks into an Economics 101 course, one encounters the “incidence of taxation” and learns why tax-the-rich and tariff-the-Chinese are fallacious and self-harming strategies. For the past 250 years or so, political leaders have gone through an endless cycle of learning this logic and then forgetting it.

Congress and the president can legally determine who writes the check for a tax or tariff, but they have no power to determine who bears the burden of embodied in that check—who suffers its ill effects. The Wikipedia article on tax incidence, explains the concept as follows:

“Economists distinguish between the entities who ultimately bear the tax burden and those on whom the tax is initially imposed. The tax burden measures the true economic effect of the tax, measured by the difference between real incomes or utilities before and after imposing the tax, and taking into account how the tax causes prices to change. For example, if a 10% tax is imposed on sellers of butter, but the market price rises 8% as a result, most of the tax burden is on buyers, not sellers.”

Sellers in this example write the check, but they pass 80% of the cost along to buyers, sellers are a little worse off and buyers are a lot worse off. Plus, some sellers stop selling altogether and some buyers stop buying. For a real-world example, consider Congress’s populist plan in 1990 to stick it to the rich by imposing a tax on certain luxury goods. As described by the Wall Street Journal:

“Starting in 1991, Washington levied a 10% luxury tax on cars valued above $30,000, boats above $100,000, jewelry and furs above $10,000 and private planes above $250,000. Democrats like Ted Kennedy and then-Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell crowed publicly about how the rich would finally be paying their fair share and privately about convincing President George H.W. Bush to renounce his ‘no new taxes’ pledge.”

Congress soon discovered that the tax saddled the rich with modest burdens while punishing people of modest means severely. The problem lay in what economists call “elasticity,” which regular folks call “price-sensitivity.” Regardless of who writes the check, the larger burden falls on the side of the market that is less price-sensitive—the side that has fewer options. In the case of luxury goods, it turned out that the rich could easily change their spending habits and purchase luxury goods not encompassed by the tax. Put a big tax on yachts, and some rich people will simply stop buying yachts and start buying waterfront condos, islands, ski chalets, works of art, or whatever else strikes their fancy. On the other hand, the people who build yachts are blue-collar folks with limited employment options. They either sell the boats for less or they stop selling altogether.

The Wall Street Journal article explains what happened after the luxury tax became law in 1991:

“The taxes took in $97 million less in their first year than had been projected -- for the simple reason that people were buying a lot fewer of these goods. Boat building, a key industry in Messrs. Mitchell and Kennedy's home states of Maine and Massachusetts, was particularly hard hit. Yacht retailers reported a 77% drop in sales that year, while boat builders estimated layoffs at 25,000. With bipartisan support, all but the car tax was repealed in 1993, and in 1996 Congress voted to phase that out too.”

BAD IDEAS, LIKE BAD PENNIES, ALWAYS TURN UP.

Both political parties in America are now enamored of the idea of punishing someone via taxation; the parties merely disagree over whom to villainize. Democrats often focus on “the rich,” while much of the GOP’s bile focuses on foreign nations—China in particular. Hence the Republicans’ advocacy of tariffs, which are simply taxes on imported goods.

Some tariff advocates make the mistake of assuming that the burden of tariffs on Chinese goods will fall exclusively on the Chinese, and some free-trade advocates err in the opposite direction—claiming that the burden will fall exclusively upon American consumers. As with the yacht tax, the burden of a tariff will fall on both sides, with the greater impact falling on the more inelastic side of the market—the side with fewer options. I suspect that the free-trade advocates are closer to the truth than the pro-tariff side, but that’s an empirical question and will differ from product to product.

We can say with near certainty that Americans and Chinese will both suffer when we impose a tariff on China, and both Americans and Chinese will suffer when and if China retaliates by increasing tariffs on American goods. Both economies will shrink. It’s perfectly understandable when this simple truth eludes someone who has not studied economics, but puzzling when it eludes someone in the economics profession. Consider the case of one Oren Cass, chief economist at the American Compass think tank.

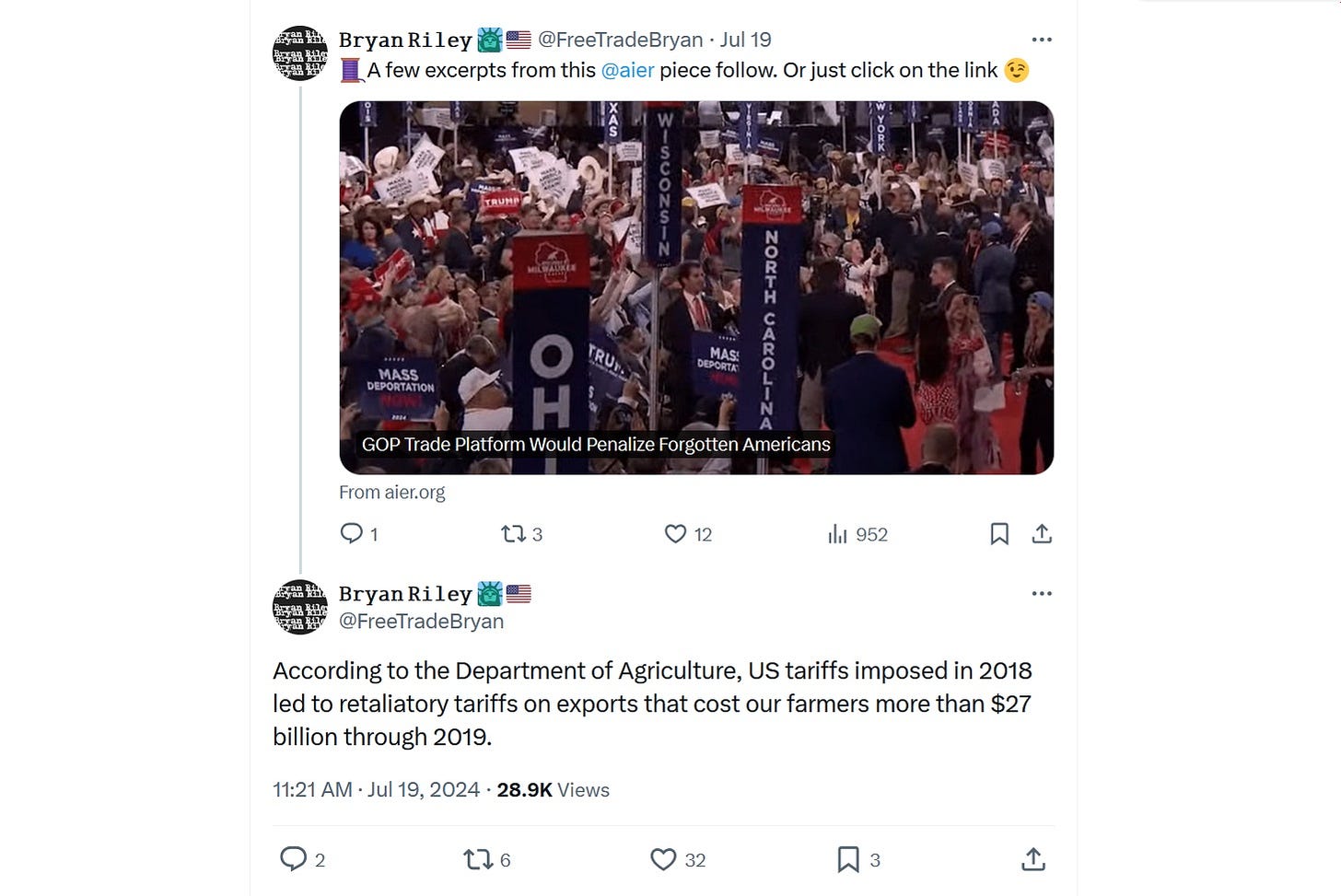

In a fine article, Bryan Riley, Director of the National Taxpayers Union’s Free Trade Initiative, criticized current Republican tariff proposals in “GOP Trade Platform Would Penalize Forgotten Americans” and praised the free-trade policies of Dwight Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan. In part, he focused on the penalties American farmers and others will pay when and if China retaliates by imposing tariffs on American goods. On X/Twitter, Riley wrote:

“According to the Department of Agriculture, US tariffs imposed in 2018 led to retaliatory tariffs on exports that cost our farmers more than $27 billion through 2019.”

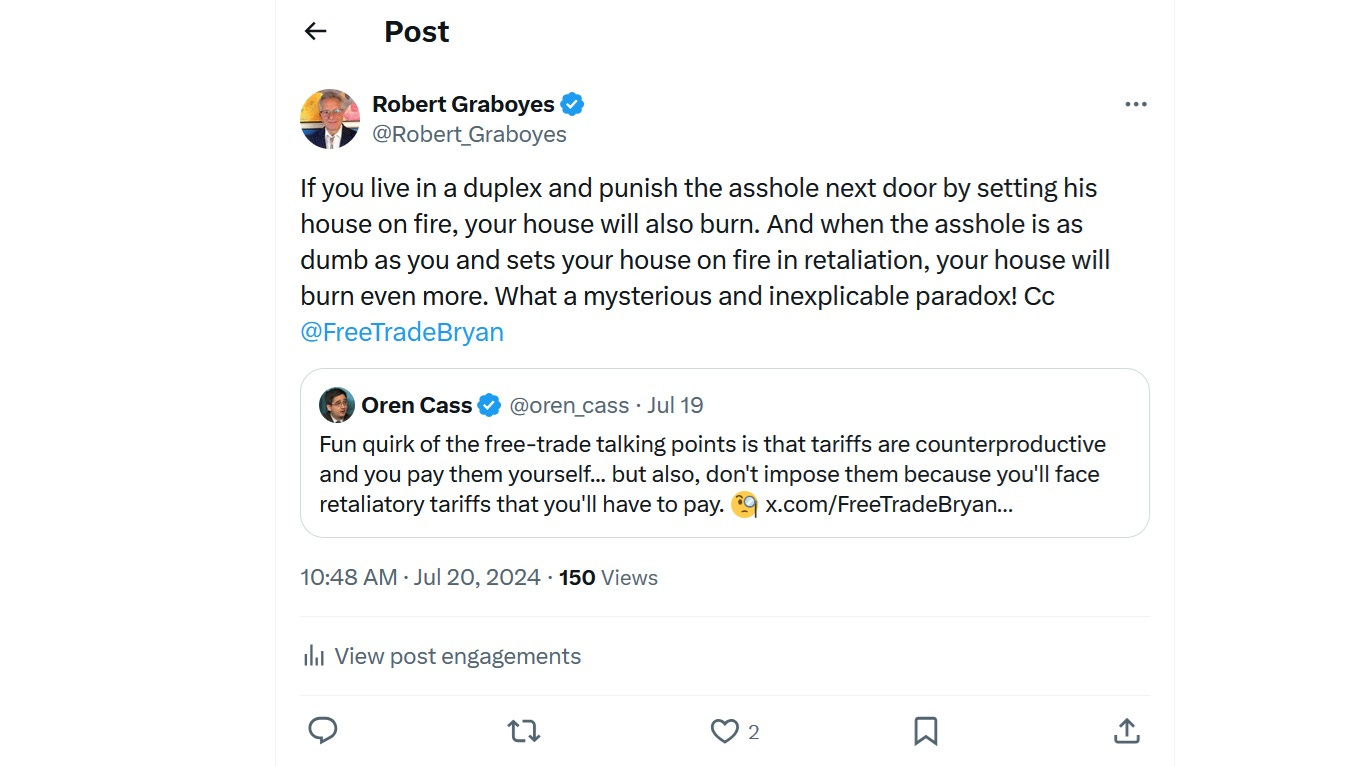

The aforementioned Oren Cass replied to Riley. He seemed to think that he had caught Riley in a logical fallacy:

“Fun quirk of the free-trade talking points is that tariffs are counterproductive and you pay them yourself... but also, don't impose them because you'll face retaliatory tariffs that you'll have to pay.”

But, as one learns a few weeks into Econ 101, there’s nothing remotely fallacious about Riley’s point. I responded to Cass with a metaphor:

“If you live in a duplex and punish the asshole next door by setting his house on fire, your house will also burn. And when the asshole is as dumb as you and sets your house on fire in retaliation, your house will burn even more. What a mysterious and inexplicable paradox!”

Economist David Henderson makes the same point in his ironically titled “Oren Cass Spots a Contradiction Among Free Traders.”

“If someone says that U.S. consumers bear all of the burden, then that someone is almost certain to be wrong. If someone says that U.S. consumers bear none of the burden, that someone is also almost certain to be wrong. … Now consider retaliatory tariffs. The same reasoning applies.”

Taxes and tariffs are perfectly fine tools for raising government revenues or for assuring that less of some product is produced. But it’s a fool’s game to try using taxes and tariffs to mete out precision punishments on specific individuals or groups—unless you don’t care how much you hurt yourself.

LEONARD READ: “I, PENCIL”

Taxes and tariffs are notoriously inaccurate tools for punishing selected groups. One of the reasons for this is that the production of and good or services involves vast, complex, ever-changing webs of products and market—making secondary and tertiary effects difficult to foresee. One of the most beautiful literary treatments of this interconnectedness is Leonard Read’s 1958 essay, “I, Pencil,” which examines the world markets and trade routes that go into the creation of something as seemingly simple as a pencil. In 2012, the Competitive Enterprise Institute made the above 6-minute video, which does a lovely job of encapsulating Reed’s classic essay. Read’s original essay is here, along with accompanying essays by Milton Friedman and Don Boudreaux.

I read somewhere the aphorism "Corporations don't pay taxes. They collect taxes."

Excellent — thank you. When the most satisfying urge is to punish the “libs/right/rich/anyone-whom-I-don’t-like,” usually it comes back to bite. Unfortunately punishment is too often the lowest, most juicy fruit on the tree.