Viewer, Puzzler, Pleader, Seer; Apparatchik, Engineer

"Economics isn't a science" misunderstands both economics and science. (Plus, Bhagwati's Nobel.)

Paid subscriptions help keep Bastiat’s Window going. Free subscriptions are deeply appreciated, too. If you enjoy this piece, please click “share” and pass it along.

This is an excerpt from my not-yet-published book, Fifty-Million-Dollar Baby: A Skeptic’s Eyes on Economics, Ethics, and Health. The goal is to edit the manuscript in plain view—to seek your comments, corrections, and suggestions. A few passages of this piece are adapted from my “Viewer, Puzzler, Pleader, Seer,” published in the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond’s Equilibria magazine (Winter 1996/97).

Last week, a reader I’ll call “Jack” emailed me to explain why, in his view, economics isn’t really science—a truism I’ve heard for forty-some years. Unlike the natural sciences, critics say, economics suffers from unrealistic assumptions, messy data, confounding variables, failed predictions, intractable disagreements, misguided policies, subjective distortions, and political biases. Natural sciences are different, they tell me. Like, for example, virology. Scientists working on COVID have provided nothing but airtight assumptions, pristine data, crystal-clear chains of causality, dead-on-accurate predictions, harmonious agreement, relentlessly successful policies, serenely dispassionate reasoning, and near-saintly absence of politics from their pronouncements. (For those nodding in agreement, please refer to Poe’s Law.)

Economics is as much a science as virology or physics. Same methods, same purposes. Arguing otherwise underestimates economics and overestimates natural science. As discussed recently in Bastiat’s Window, physicist Max Born described how methodological blinders and antisemitism distorted mid-1940s physics. Ten or more recent Bastiat’s Window essays have described how the decades-long madness of eugenics swept over medicine, biology, genetics, public health. All natural sciences suffer the same fallibilities as economics—less obviously, perhaps.

In a tribute to his former professor, Jagdish Bhagwati, Nobel laureate and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman recounted a story I also heard while studying under Bhagwati at Columbia in the 1980s:

“Jagdish explained to us his personal theory of reincarnation, which was that if you are a good economist, a virtuous economist, you are reborn as a physicist, and if you are an evil, wicked economist, you are reborn as a sociologist. … [T]he point is the joke is not about sociologists or physicists. The joke is about economists. It’s about people who … aspire to what they imagine physicists to be, to this rigor and certainty and mathematical complexity.”

For me, Bhagwati’s quip reflects three problems that generate the perception that economics isn’t really science:

Economists play four distinct roles (as economists), and they’re sloppy about indicating which role they’re playing at any moment. I once called these roles the Viewer (observer), Puzzler (analyst), Pleader (advocate), and Seer (forecaster). Natural scientists play the same four roles and, like economists, often intermingle them inappropriately.

Economists (and natural scientists) play two additional roles where they consume economics but don’t produce economics. The Engineer (policymaker) seeks to manage an economy or some portion thereof. The Apparatchik (functionary) parrots or bolsters some Engineer’s vision. Over the 19th and 20th centuries, however, “economics” erroneously became synonymous in the popular imagination with “managing the economy” or “managing society.”

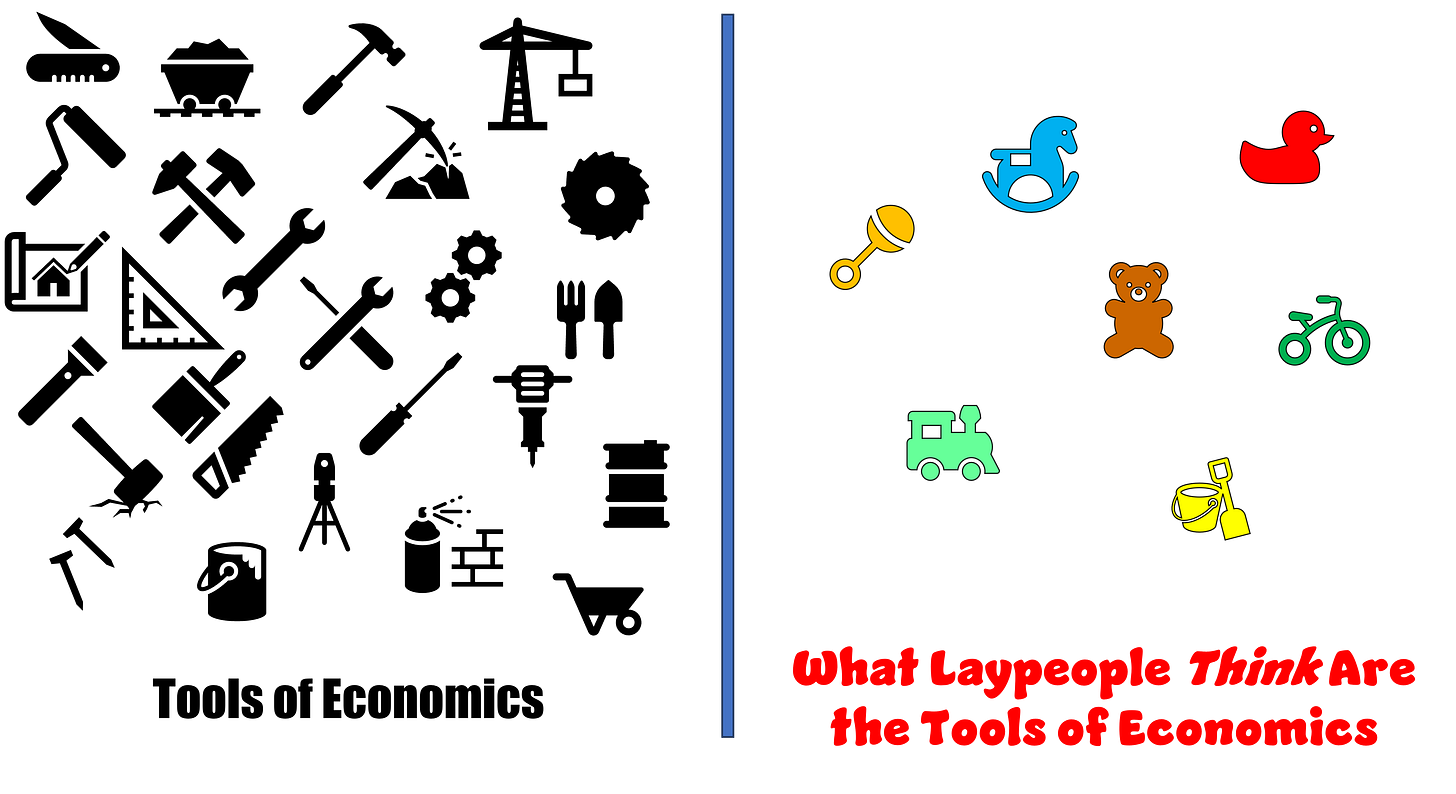

Economists have an unwarranted surplus of self-doubts, while natural scientists have an undeserved deficit of such doubts. When top-tier economists write for popular audiences, their output tends toward, “Let me share truths I’ve discovered by using complex tools you wouldn’t understand.” Top-tier physicists (e.g., Albert Einstein, Werner Heisenberg, Max Born, Richard Feynman, Stephen Hawking) happily tell popular readers, “Let me show you my incredible toolkit and how I use it to explore the Universe.” Thus, laypeople commonly assume that economists’ tools go no farther than the simplistic assumptions and models of ECON 101.

Problem #1: Viewer, Puzzler, Pleader, Seer

Let’s examine the first four roles:

The Viewer uses economics to ask, “What happened?” “Did food prices rise in 2022?” “Did they rise faster than general inflation?” “Do we mean food prices in upscale shops or discount supermarkets?” The Viewer sorts through data to make observations, not to explain why prices rose, recommend changes, or forecast the future.

The Puzzler asks, “Why did that happen?” “Why did food prices rise in 2022?” “Bad weather?” “Increasing farm wages?” “COVID-provoked supply shortages?” Puzzling doesn’t involve advocacy or forecasting.

The Pleader asks, “What should happen?” “Lower tariffs to decrease food costs.” “Reduce red-tape on food producers.” Subjective opinions are overlaid upon objective observations.

The Seer asks, “What will happen?” “Food prices will rise 8% in 2024,” or “If the government imposes a new tariff, then food prices will rise by 11%.”

We see the same roles in the natural sciences:

The Viewer says, “You have COVID." He offers no take on whether COVID originated with a lab leak or a wet market, whether masking and vaccination actually stave off COVID, or how many deaths we should expect in the next year.

The Puzzler says, “COVID originated with a lab leak and is caused by an airborne virus.” She might offer advice on the efficacy of masking and vaccination, but does not implore people to take action.

The Pleader says, “People should wear masks while visiting hospitals,” or “We should focus our efforts on the most vulnerable populations.” Pleading isn’t the same as predicting.

The Seer says, “There will be 4,200 cases of COVID in our county this year.” Or, “If 80% of county residents are vaccinated, cases will decline by 1,400.”

Problem #2: Apparatchik, Engineer

Viewer, Puzzler, Pleader, and Seer all fall under the umbrella of economic science. But as Apparatchik and Engineer, practitioners use economic science but, I would argue, they are not acting as economists/economic scientists. (Note: I used “Apparatchik, Engineer” (in that order) in the title because it rhymes with and continues the trochee meter of “Viewer, Puzzler, Pleader, Seer.” I reverse the order here for easier logical progression.)

The Engineer wishes to manage society, for either selfish or altruistic reasons. “I’ll offer subsidies to spur growth.” “I’ll raise tariffs to protect domestic industrial jobs.” “I’ll pay race-based reparations to promote ‘equity.’”

The Apparatchik gathers or disseminates economic information to justify some Engineer’s goal. “I’ll hunt for data that support the idea of corn subsidies.” “I’ll cherry-pick data to embarrass lockdown skeptics.”

A structural engineer who builds a bridge uses physics in his work, but is not acting as a physicist. If the bridge collapses, that’s a failure of engineering, not physics. Similarly, when Fed officials lower interest rates ito spur growth, they use economics, but they’re not acting as economists—regardless of the titles on their résumés.

Yet, in the popular imagination, “economics” has become synonymous with “managing the economy.” In explaining why he thought economics isn’t a science, “Jack” wrote:

“Communism would work in Heaven, and Heaven is the only place it could/would work.”

“I don't think there is any good way or maybe even any bad way to prevent economic swings and find a steady middle growth path.”

Here, he’s channeling the two men most responsible for the idea that “economics” is synonymous with “managing the economy”—Karl Marx and John Maynard Keynes. In fact, broad swathes of economics are dedicated to explaining why economies are not manageable in the way that Keynes or Marx or their followers imagine. In very different ways, the Nobels earned by Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman, George Stigler, James Buchanan, Ronald Coase, Gary Becker, Robert Lucas, Robert Mundell, Vernon Smith, Elinor Ostrom, and others reflect this skeptical view.

Science is a process for accumulating, organizing, and testing knowledge—not a recipe book for controlling what is under observation. Meteorologists cannot control the weather, and yet meteorology is undeniably science. Virologists, even those empowered to micromanage civic life, could not will COVID to depart our shores; and yet, virology is undoubtedly science.

Regardless of titles and credentials, those mandating social distancing, masks, and quarantines and offering perplexing ad hoc exceptions were acting as Engineers, not as scientists. Admittedly, the line between Apparatchik and scientist can be subtle. If the virologist pores over data to determine whether masks slow the spread of COVID, he’s a Puzzler. If he pores over those same data to justify his boss’s mandate, he inhabits the ranks of Apparatchiks.

When Engineers promise to manage the economy or manage COVID, there are whole classes of Apparatchiks—journalists, politicians, bureaucrats, activists—who view their pronouncements the way that ancient peoples viewed solar eclipses—as occasions for prostrating themselves and hunting down whomever doubts the shaman’s strategy for appeasing the sun-eating devil. When public health “experts” said in 2020 that your grandpa should die alone in a hermetically sealed hospital room, but that 20,000 people should simultaneously lock arms and march outside the hospital to protest racism—journalists nodded obediently. Their allegiance was not to “science,” but rather to “The Science™.”

Don’t misunderstand me: the speed with which virologists and others mapped out COVID’s genome and developed vaccines was an astounding scientific feat. But Engineers and Apparatchiks left the bounds of science when they claimed that scientists knew in advance the side effects of vaccines, the efficacy of masking, the virus’s origin, and the virtues of school closings.

Problem #3: Underestimating the Toolkit

“Jack” said this about the supposed distinction between economics and natural science:

“Science is logical—even quantum physics, though no one really understands it yet. … [Economics has] too many exceptions, such as the South Sea Bubble … to make it a science. … It counts on people making rational choices on the basis of reality. ”

These statements critique a two-dimensional cartoon version of economics. Again, economists bear considerable responsibility for this particular misunderstanding. They dislike explaining their logic to laypeople, in part because laypeople are often adamant that they already know that logic—often to the point of smugness. This noncommunication leaves laypeople free to devise their own erroneous concepts of what constitutes economics.

ECON 101 begins with the economist’s assumption that people are rational calculators and behave accordingly. Economists don’t actually believe this to be an accurate description of people, but it’s a tremendously useful fiction for beginning to analyze economic behavior. The rich literatures of economics depart sharply from the rational actor model. Robert Shiller and Eugene Fama shared the 2013 Nobel for analyzing events like the South Sea Bubble—while disagreeing vehemently on the essential nature and even on the existence of bubbles. Vernon Smith won his Nobel for introducing experimental techniques into economics, and his acolytes conjure up and analyze speculative bubbles in their laboratories all the time. Daniel Kahneman is a psychologist whose whole oeuvre has been to examine how people are irrational. Richard Thaler studied “nudges”—small environmental changes that profoundly affect the behavior of humans with less-than-perfect rationality. Herbert Simon offered the idea of “satisficing”—how people make decisions when rationality is not feasible.

“Jack” mentioned quantum physics, whose originator, Max Planck, once told Keynes that he had considered studying economics but found it “too difficult.” Keynes’s remembrance offered the same line of argument as “Jack”:

“Economics is a science of thinking in terms of models joined to the art of choosing models which are relevant to the contemporary world. … [U]nlike the typical natural science, the material to which it is applied is, in too many respects, not homogeneous through time.”

Keynes helped to solidify the notion that Economist and Engineer are synonymous. I think “Jack” erred in his observations, but he was in good company—including the single most important economist of the 20th century. Disagreement, uncertainty, changing opinions, gaps in knowledge, humility? In economics, as in physics or virology, these are the essence of science. Science is a set of tools by which one asks questions and the honest and dispassionate use of those tools. Science is not a set of answers, festooned with ribbons, settled for all time, conferring control and pre-packaged propaganda to those who possess its secrets.

Lagniappe

Bhagwati’s Nobel Prize

During my days as a graduate student at Columbia University, none of our professors had yet won the Nobel Prize in Economics. (Formally, it’s the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel or, slightly shorter, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences). Which faculty member would be the first to win the prize was a recurring topic of our discussion. One of the more common guesses was Jagdish Bhagwati, whose quip on economists, physicists, sociologists, and reincarnation is featured in the main article above.

Four decades later, three of our professors (William Vickrey, Robert Mundell, and Edmund Phelps) have won prizes, along with five others who were associated the department before or after our time (Joseph Stiglitz, James Heckman, Gary Becker, Franco Modigliani, and George Stigler)—but no prize for Jagdish Bhagwati. Bhagwati stands as one of the most highly acclaimed international trade economists of his generation, and precisely why he has never received the Nobel has long been a matter of speculation. For a long period, there was annual speculation that this was Bhagwati’s year—but that year has never come. Bhagwati himself has commented on the fact and said long ago that he had given up hope of receiving the Prize.

The repeated speculation became enough of a meme that, in 2010, he was finally awarded a Nobel—on an episode of The Simpsons. When the episode aired, I phoned a Columbia classmate and said, “I’ll bet Bhagwati hates that episode.” My friend said, “I’m going to disagree. I’ll bet he loves it.” While we talked, I went to Bhagwati’s faculty webpage. There, where one would normally find a staid photograph of the professor, there was, instead, his caricatured image from The Simpsons video clip. “You win,” I told my classmate. Thirteen years later, his faculty page still mentions his cartoon appearance. Kudos to the professor for taking the joke in such good spirit.

I don’t have a problem with economists (which I call myself) calling economics a science. I prefer to distinguish natural sciences from social sciences, but that’s just me. We used to get a lot of grad students from the engineering college because they preferred the mathematical rigor of economics, but I always cautioned people not to confuse the use of mathematics with truth, and pointed at the sociologists.

The point that David Kelly made, comparing economics to climatology, reminded me of the discussion around “complex” vs “complicated.” (It also reminded me of Asimov’s “psychohistory” in the FOUNDATION series, but I’m a sci-fi nerd).

If “Jack” were to substitute “climatology” for “economics” in that first sentence, he wouldn’t be wrong.