Virginia’s 12½ Presidents

Plus, a 4,700-mile trek for a bowl of peanut soup and a plate of collard greens

Today, I’ll share a bit of trivia that I often save for my fellow Virginians—residents of a state that has long been obsessed with history. The question is, “Who were the thirteen presidents born in Virginia? Or, perhaps more accurately, who were the twelve-and-a-half presidents born in Virginia?” The question stupefies my listeners, as Virginia schools drilled into us that eight U.S. presidents saw their first light in our state. So, who are the other five (or four-and-a-half) presidents of whom I speak? I’ll note first that the stories of all thirteen men are deeply intertwined with Virginia’s legacy of slavery.

Virginia’s State Capitol has long featured the great marble statue of George Washington by Jean-Antoine Houdon and, nearby, marble busts of the other seven Virginia-born U.S. presidents: Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor, and Woodrow Wilson. Virginia schoolchildren have long heard their state referred to as the “Mother of Presidents,” though decades ago, some wag said it was more properly “the Mother of Presidents — Who Hasn’t Been Pregnant in a Century.” Virginia’s U.S. presidents were a complex and strikingly accomplished lot. Unfortunately, a common thread runs throughout the list. The first seven were all slaveholders. Woodrow Wilson was a child in the time of slavery and, a half-century after Emancipation, he arguably did more damage to race relations in America than did any of his slaveholding predecessors.

As I tell my Virginia friends, there were five other Virginia-born presidents, for a total of thirteen; or maybe four-and-a-half more, for a total of twelve-and-a-half. The histories of these other four presidents and one sort-of president were also bound up with issues related to slavery. So, who were the other five? The key lies in noticing that I did not say there were thirteen United States presidents. With that in mind, here are the others:

[1] Fulwar Skipwith, Governor (sometimes referred to as President) of the Republic of West Florida (1810). The brief-lived Republic of West Florida existed from September 27, 1810 till December 10, 1810, and Skipwith became governor/president on November 7. Adding layers to this trivia, the country was officially known as the “State of Florida” and was nowhere near today’s State of Florida. Under Spanish colonial rule (and, at times, British rule), Florida included today’s Florida, plus the coastal chunks of today’s Alabama and Mississippi, plus the portion of today’s Louisiana north and east of the Mississippi River—including Baton Rouge. (The French had some involvement with that corner of Louisiana, too.) After America received the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803, ownership of one tract of land remained uncertain. As shown on the map, the area comprises the eight “Florida parishes” of contemporary Louisiana. In late 1810, American settlers in this area of present-day Louisiana declared it to be the State of Florida, also known as the Republic of West Florida. Fulwar Skipwith, born in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, had settled in the area, where he owned a plantation (staffed by slaves, I presume). When West Florida declared its independence, Skipwith was chosen to head the new nation. He anticipated that it would eventually be absorbed into the U.S., which seems to explain why his title was “governor,” rather than “president.” He is thus the one I refer to as a “half-president,” since he acted as a president but seems never to have borne the title. Ultimately, the new republic put the U.S. at odds with Spain, with whom the U.S. otherwise had good relations. The whole thing irritated President Madison, who soon sent troops in and successfully claimed the region for the U.S.

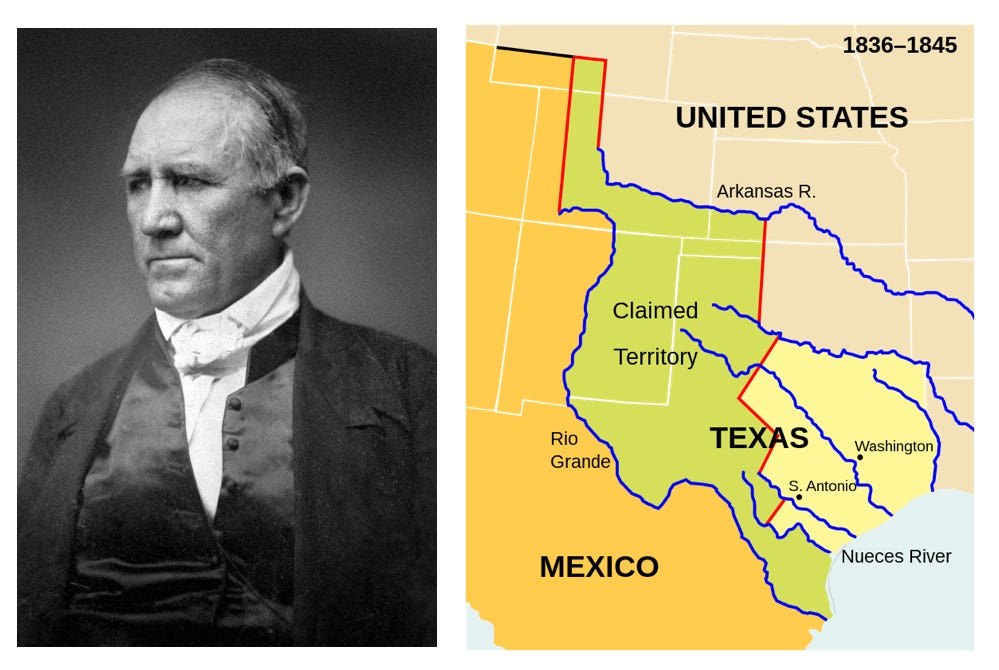

[2] Sam Houston, President of the Republic of Texas (1836-1838, 1841-1844): Born in Rockbridge County, Virginia, General Houston served as the 1st and 3rd presidents of the Republic of Texas, which declared its independence from Mexico in 1836 and was absorbed into the United States in 1845. Houston was a slaveholder, but had complex views on the institution. During his presidency, Texas imposed the penalty of summary execution on those illegally importing slaves and barred bounty hunters from capturing escaped slaves. Houston opposed the expansion of slavery into the Western U.S. and refused to support the Confederacy when Texas seceded from the Union in 1861—thus ending his political career.

[3] Joseph Jenkins Roberts, President of the Republic of Liberia (1848-1856, 1872-1876): Born free in Norfolk, Virginia, Roberts emigrated to Liberia, on the West African coast, at around age 20. Liberia had been founded in the 1820s by the American Colonization Society, and was intended to be a place to which free African Americans could go, leaving the slaveholding U.S. behind. Roberts became a merchant in Monrovia, entered politics, and became the nation’s first president (and later its seventh president).

[4] James Spriggs Payne, President of the Republic of Liberia (1868-1870, 1876-1878): Spriggs, born free in Richmond, Virginia, appears to have emigrated to Liberia on the same ship as Joseph Jenkins Roberts, who was ten years his elder. In his first stint as president, he sought to end the slave trade that still continued, and he sought to improve relations with the indigenous peoples of the area. During his second round in the office, the economy suffered, but Payne achieved diplomatic recognition from most European and North American countries.

[5] Anthony William Gardiner, President of the Republic of Liberia (1878-1883): Born in Southampton County, Virginia, Gardiner emigrated to Liberia during childhood—two years or so after the arrival of Roberts and Payne. His family emigrated shortly after Nat Turner’s Rebellion occurred in the county. While president, his True Whig Party gained a tight grip on the nation’s government—and they did not relinquish that control until a 1980 coup d'état overthrew the last Americo-Liberian government to rule the country.

In a very recent BASTIAT’S WINDOW column, I mentioned that Joseph Jenkins Roberts spent a number of years in my hometown of Petersburg, Virginia. Not all of his family emigrated, and I personally knew at least one descendant of those who had remained. On a 1984 business trip to Liberia, my plane landed at Roberts International Airport (Robertsfield). While in the country, I stood beneath Roberts’ statue in Monrovia. I’m something of a foodie, and one afternoon, I went for lunch at a “chop shop”—a little eatery in a tar-paper-clad shack. When they handed me the menu, my eyes lit up. The offerings were exactly what one would find in an elegant country inn in Virginia—peanut soup, collard greens and cabbage, and so forth. I had been on the road for around six weeks, and it tasted like home. And it deepened my appreciation for those who had traveled 4,700 miles to escape a benighted institution.

Fulwar Skipwith’s birthplace was just a few miles west of my own, and James Spriggs Payne’s was 23 miles to the north, in Richmond, where I lived for over 20 years. The Mother of Presidents was more fecund than our history teachers revealed, or likely knew.

Phi Alpha Theta. I have a better than average knowledge of American history but you always surprise me with things I didn’t know.

¡Gracias, profesor!

Yup. But no presidents born in either during the time that Virginia held them. At this point, I think both VA and WV would object to reunification.