Today marks a happy tale of rebirth—of Notre-Dame de Paris rising phoenix-like from the ashes of the fire that nearly destroyed one of Christianity’s most revered structures. On April 15, 2019, a blaze destroyed much of the cathedral’s roof and flèche (spire). At the time, the damage seemed so terrible that some wondered whether it was the end for the marvel built between 1163 and 1345. Notre-Dame has a history of resilience, however, and soon, plans for its restoration began to emerge. Some radical glass-roofed designs briefly made the rounds, as shown in this link and in the following video:

But in the end, the restoration more or less replicated the structure that had stood before the fire—a traditional roof with modern fire suppression technologies added to forestall another conflagration. This weekend (December 7-8, 2024), the world watches the glorious reopening of this architectural and spiritual marvel.

The day after the 2019 fire, I wrote an essay on the tragedy and on the personal meaning the cathedral held for me and my wife. Below, I republish that essay, edited lightly to bring its timeframe forward from 2019 to 2024.

Notre-Dame and the Myth of Timelessness

Being Jewish, I have no natural affinity for Notre-Dame de Paris. Yet a few personal memories have bound my thoughts and sentiments to the great cathedral for many decades. 2019’s disaster broke my heart, but even in this horror, I found a sense of uplift.

Let me describe my tenuous connections to Notre-Dame. Getting there requires some meandering through economics, but all for a purpose.

In 1981, while at Columbia University, I worked as a research assistant for Don Patinkin—one of the great monetary economists of the 20th century and, briefly, president of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Patinkin was a kindly gentleman but meticulous and demanding enough to drive colleagues insane. Those characteristics didn’t bother me; working for him was pure pleasure.

Patinkin’s Money, Interest and Prices was for a time considered by some to be the late century’s second-most important work on monetary theory. When I worked with him, he was seeking the historical tributaries leading to the century’s most important monetary work—John Maynard Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. My job was helping Patinkin produce a book: Anticipations of the General Theory? And Other Essays on Keynes.

By reputation, economists are notoriously disinterested in the historical trails that led to present-day thinking. Many act as if the present state of economic reasoning was present at the Big Bang and will stand immutable until the sun flickers out. Given his outsized reputation as a theorist and empiricist, I asked Patinkin what led him to the little-appreciated doctrinal history. He said he liked the field because practically no one else did. If you’re the only one who cares, he said, it’s easy to be the leading authority on the topic.

My first assignment was to determine whether the first edition, first printing of Keynes’s book employed the Oxford comma. Was it The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money or The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money? Pre-Internet, this required crawling through the gloomy stacks of libraries around Manhattan. It took a significant effort to find a first edition from 1936, and I proudly brought Patinkin the book. He shook his head and said this was a first edition, but not the first printing. Back I went. After some days, I found the rare text somewhere in Manhattan and brought it to him. He beamed like a child.

Why, I asked, did he care so much about the comma if, as apparently was the case, Keynes didn’t. He jutted his finger into the air, saying:

“Because in Paris, there is the great Cathedral of Notre-Dame. And hundreds of feet up in the air, there are gargoyles, some of which are virtually never seen by anyone. Yet, hundreds of years ago, the sculptors who made them put great care into making them as perfect as they could, knowing even then that no one would ever be able to appreciate them.”

Patinkin’s offhand comment left a deep impression, altering my behavior a bit, making me a better economist and a better person.

Two years later, my then-future wife and I took our first great trip. We traveled together to Paris—the first time I had ever left the United States—after which, I left her and flew south to Nigeria. The most memorable portion of our stay in Paris was a visit to Notre-Dame. My small, history-obsessed Virginia hometown fawns over “historical” houses a mere 150 years old. At Notre-Dame, Alanna and I walked through the most impressive building we had ever seen—begun over 800 years earlier, built mostly by illiterate workers using muscle-driven tools.

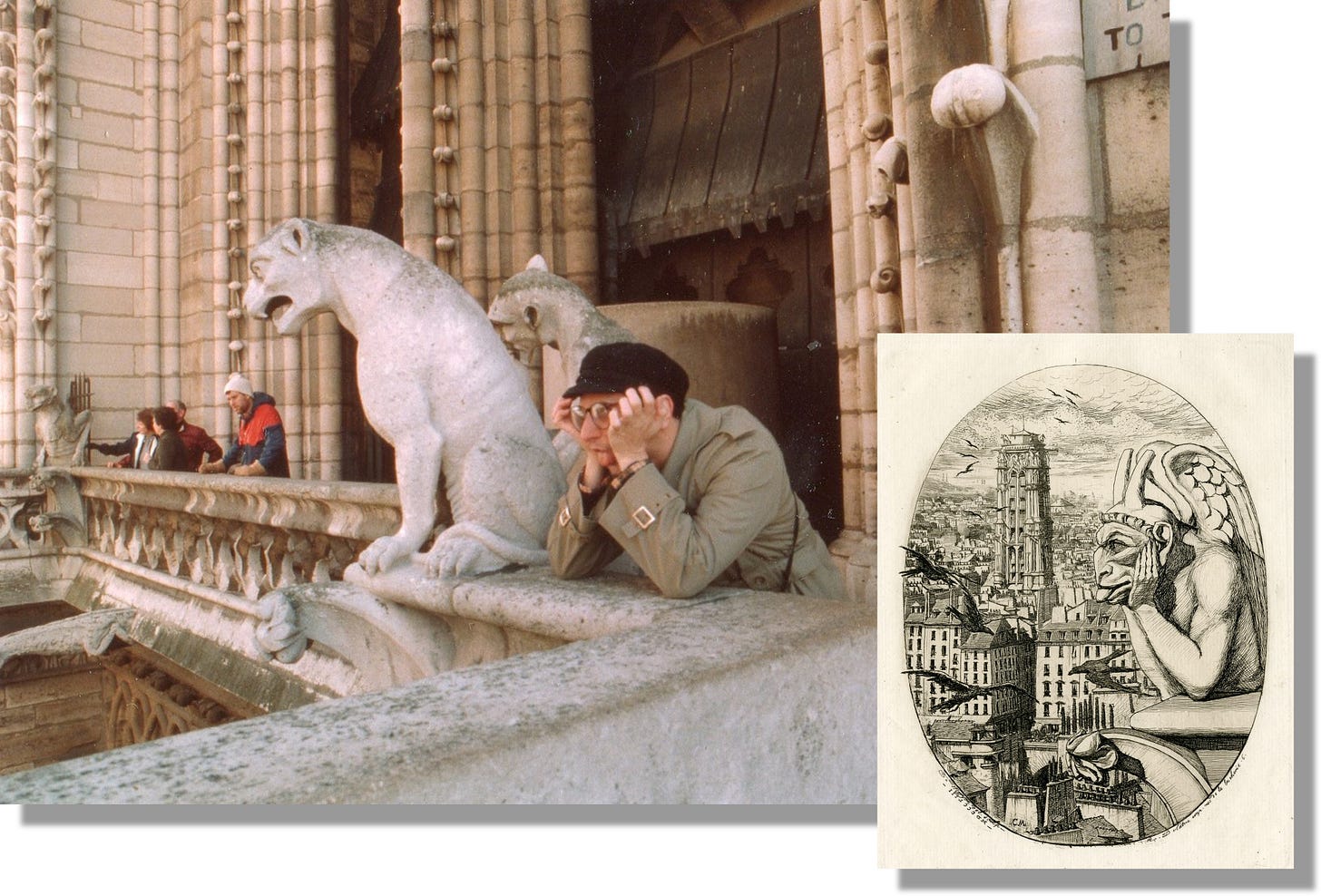

Patinkin’s words about precision and pride of authorship were on my mind with every piece of stonework I saw. Alanna and I climbed to the top to see the menagerie of gargoyles, chimeras, and other mythological beasts. The accompanying photo is my 1983 imitation of Notre-Dame’s best-known carving—“Le Stryge” (“The Vampire”).

In 2019, the world mourned the fire’s horrific destruction. Most gut-wrenching were videos of the collapse of the iconic spire which, before the fire, soared 300 feet into the air. But in that heartbreaking collapse, I maintained hope. I investigated how old the spire itself was. The answer surprised me; it was built in the mid-19th century—around the time the store my parents once owned in Virginia was built. “Le Stryge” dates from around the same time—part of the massive restoration partially inspired by Victor Hugo’s 1831 Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame). The building was completed in 1345, but it was never “finished.”

Notre-Dame of 2019, like the economic doctrine that Don Patinkin studied, was not an immutable, unchanging structure. Over the centuries, the cathedral was ravaged by vandals, religious fanatics, revolutionaries, armies, and the general rot of ages. It was reborn time and time again, and I had faith the day of the fire that it would be reborn once more.

Five years ago, the internet was filled with laments. Notre-Dame, some pined, would never be the same, and repairs would not likely be completed in our lifetimes. But I wrote back then that even long decades of repairs could be thought of as part of the beauty and life of a cathedral. The original architects knew they would never see their creations finished. Like the sculptors Don Patinkin described to me long ago, the architects built for the Ages, not for themselves.

And yet, just a bit over five years later, Notre-Dame de Paris is back, as glorious as ever. A century from now, pilgrims and tourists will probably look upon elements of the 21st-century restoration and assume, erroneously, that they date from the 12th or 13th centuries. Most likely, Notre-Dame will see more disasters and rebirths in the coming centuries. For me, a peculiar glory and humility comes from knowing that the great edifice will live on long after I am gone—that it is my privilege to witness only a small fraction of its long life.

Vive la Cathédrale.

MEDIEVAL MEETS MODERN

The reconstructed Notre-Dame de Paris combines Medieval and Modern elements. So do “Filamentos” (my jazz/blues piece based on Renaissance madrigals) and “Chiaro” (my wife’s abstract painting based on Rembrandt’s “The Feast of Belshazzar.”) Enjoy both. (Alanna’s art is at ASGraboyesArt.com.)

Fascinating story about Don Patinkin. I'm always envious of people who knew and worked with famous people, be they economists, musicians, philosophers, or physicists. I enjoyed your music, too, and your wife's painting. I have a question, if you will indulge my curiosity. With your compositions, I know you are playing the piano; whence cometh the other instruments?

And I went back to see if you used the Oxford comma, you did.