We Beg Your Pardon, We Never Promised You the Rose Garden

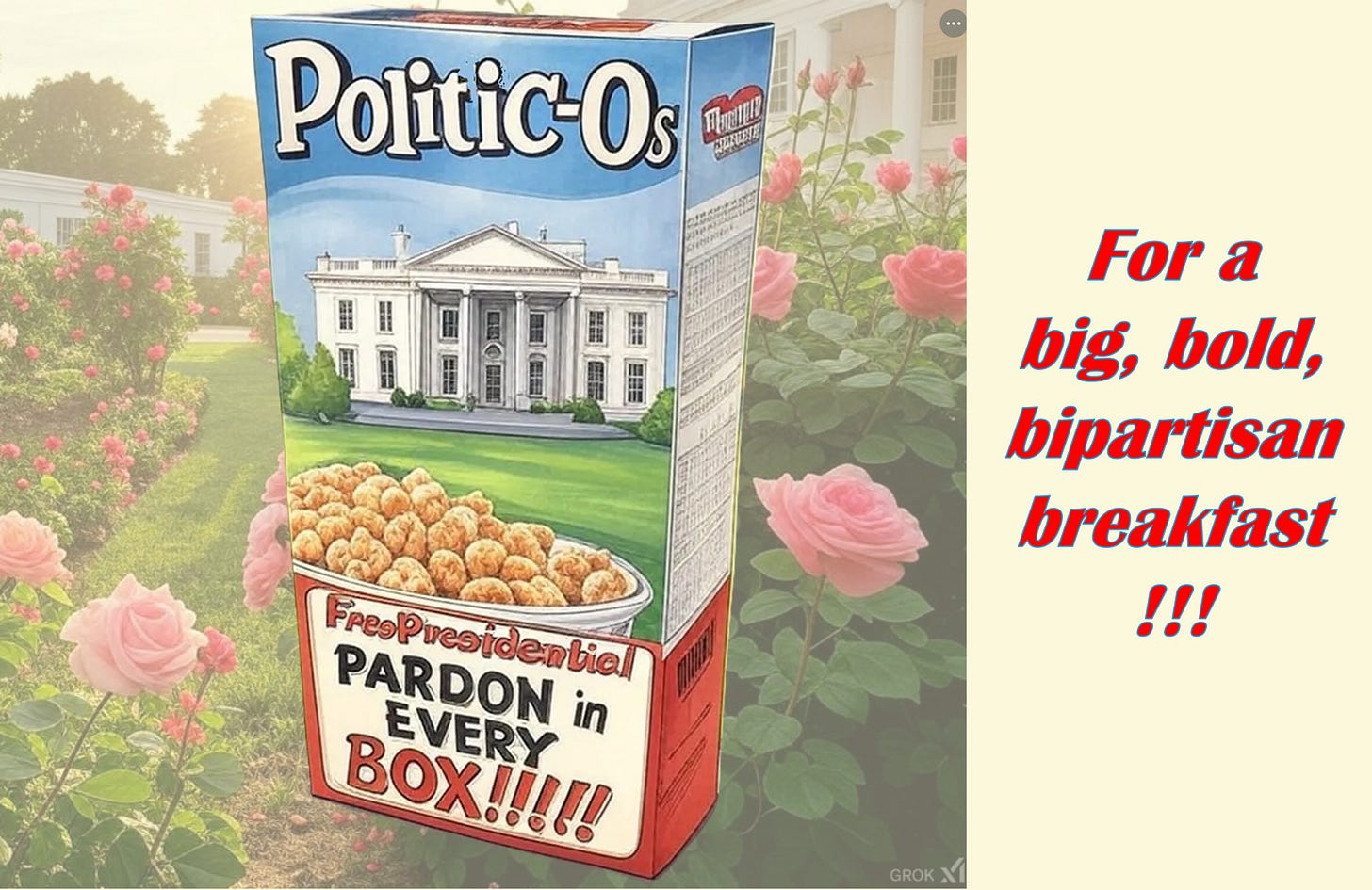

A modest proposal reining in the accelerating arms race in issuance of presidential pardons and commutations—a constitutional vestige of Seventh Century England

The assembly line production of pardons and commutations by Presidents Biden and Trump in recent weeks has made many uncomfortable about the very existence of this uniquely sweeping power—a relic of Seventh Century England’s perception that kings were God’s equivalents on earth. Stripping the presidency of this unfettered privilege has merits, but doing so would require a far-reaching constitutional amendment that would be impossible to enact and ratify in today’s environment.

But here’s a far more modest proposal that might just make sense to both parties—requiring a 90-day Public Comment Period for any names under consideration for clemency, along with the specific terms of the action being considered. Biden could still have given preemptive pardons for any crimes committed over the previous eleven years to son Hunter and five other Bidens, but he would have to have announced that possibility no later than October 22—over two weeks before the 2024 election. Donald Trump would still be free to pardon those January 6 rioters accused of violent assaults on police officers, but only after enduring 90 days of criticism by enraged Democrats, unnerved Republicans, outraged law officers, families of victims, and a lean and hungry press—all asking what happened to J. D. Vance’s January 12 statement that, “if you committed violence on that day, obviously you shouldn’t be pardoned.”

Prior Supreme Court rulings make it unlikely that Congress could impose a 90-day Public Comment Period by statute, but a brief, tightly focused constitutional amendment imposing such a requirement is at least plausible. Democrats could see it as a way to throttle Trump’s potential excesses. Republicans could see it as insurance against some future Biden (or Clinton) and (quietly) as a governor on potentially difficult-to-support acts of clemency by Trump.

Let’s take a quick look at the history of presidential clemency powers and how a 90-day Public Comment Period could change the dynamics.

THE DIVINE RIGHT OF PRESIDENTS

Ancient monarchs could confer pardons and commutations, but from the standpoint of American law, the story begins with early medieval English kings. Clemency was a literal manifestation of the Divine Right of Kings. The King in Heaven could spare a life, and King on Earth could do the same.

In “The History of the Pardon Power: Executive Unilateralism in the Constitution,” Colleen Shogan (former Archivist of the United States) notes that the power to award clemency is America’s “strongest example of constitutional executive unilateralism”—one over which the Founders struggled. The Supreme Court, she notes, has ruled that clemency powers are “not generally subject to congressional modification” or restriction:

“Alexander Hamilton introduced the concept of a pardon power at the Constitutional Convention. There was debate about whether Congress should have a role in the pardon power, with the Senate approving presidential pardons. Delegates also debated whether treason should be excluded from pardonable offenses. … … The framers of the Constitution deliberately separated the judicial function of government from the pardon power, therefore obviating concern from English jurist William Blackstone that the power of judging and pardoning should not be delegated to the same person or entity.”

Some presidents have used clemency to quell discord or heal old wounds. George Washington pardoned Whiskey Rebellion leaders. John Quincy Adams pardoned Native American participants in the Winnebago War. James Buchanan pardoned Brigham Young, and Benjamin Harrison pardoned Mormons who had engaged in polygamy. Andrew Johnson pardoned Jefferson Davis and other Confederates (bolstered by the Amnesty Act of 1872, signed by Ulysses Grant). Calvin Coolidge commuted Marcus Garvey’s mail-fraud conviction so he could be deported; Joe Biden posthumously awarded Garvey a full pardon. Gerald Ford offered limited clemency to tens of thousands of Vietnam Era draft resisters; Jimmy Carter expanded the scope of forgiveness and the number of beneficiaries. Gerald Ford famously issued a preemptive pardon for Richard Nixon.

Sometimes, clemency has been issued as a reward for services rendered. James Madison granted clemency to pirates Jean and Pierre Lafitte after they helped America during the War of 1812. The court-martialed John C. Frémont was pardoned by James K. Polk, who thought him partially guilty but wanted his services as a military leader. (Eight years later, Frémont became the first-ever Republican presidential nominee.)

Some edicts have tacitly recognized laws or judicial processes as flawed or unjust. At the behest of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner, Millard Fillmore pardoned two schooner captains who helped seventy-seven people seeking to escape slavery in the Pearl incident. Warren Harding commuted the sentence of Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs, who had been jailed for peacefully protesting World War One.

Then, there are odd edicts for well-known figures. Jimmy Hoffa, Patty Hearst, Marvin Mandel, George Steinbrenner, Susan B. Anthony (posthumously).

Recent years have seen a qualitative and quantitative change in clemency. Consider the number of edicts from the past half-century (excluding the gigantic Vietnam resister pardons): Ford (409), Carter (566), Reagan (406); GHW Bush (77), Clinton (459), GW Bush (200), Obama (1,927), Trump-45 (237); Biden (8,064); Trump-47 (approximately 1,500 so far).

Bill Clinton’s last-day pardons sparked outraged. Beneficiaries included half-brother Roger Clinton, business partner Susan McDougal, radical bomber Susan Rosenberg, and—most controversially—racketeer Marc Rich.

Trump’s first-term pardons and commutations were few in number but large in controversy. The Wikipedia article grouped his beneficiaries as “supporters and political allies,” “requests by celebrities,” “military personnel accused or convicted of war crimes, “Congressmen,” “healthcare industry” individuals, and “wealthy individuals.”

Biden’s beneficiaries were both numerous and controversial. Preemptive blanket pardons went to six family members, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Gen. Mark Milley, former Rep. Liz Cheney, Sen. Adam Schiff, and others. He commuted death sentences of 37 out of 40 federal Death Row inmates. Leonard Peltier, who murdered two FBI agents, saw his sentence commuted to home imprisonment for life. Other beneficiaries included (inexplicably) kids-for-cash Judge Michael Conahan and Illinois embezzler Rita Crundwell.

Upon his return the White House, Donald Trump immediately pardoned virtually all individuals associated with the Capitol riot of January 6, 2021—including those accused of physically assaulting law officers.

A MODEST PROPOSAL FOR PARDON REFORM

Under current law, pardons and commutations are bolts out of the blue. No matter how shocking and indefensible, they are fait accompli upon announcement. The president’s opponents can do nothing more howl at the moon. His allies, no matter how inwardly appalled, are free to shrug, sigh, and suggest moving on to other topics.

To reiterate: under my modest proposal, presidents would retain their current powers to grant a pardon or clemency to some individual, but only after announcing 90 days in advance that said clemency was under consideration. To understand how this might impact the dynamics of clemency, let’s engage in some speculative alternate history about how such an amendment would have affected recent presidents:

2000: Bill Clinton is pondering the possibility of pardoning Roger Clinton, Susan McDougal, Susan Rosenberg, and Marc Rich. He is free to do so up through noon on January 20, but only if he announces the possibility no later than October 22. Doing so will put Al Gore, Joe Lieberman, and every other Democratic candidate in America in a bitter defensive stance for the final 16 days of the election. Clinton, anxious to preserve his political legacy, omits these names from his list of potential pardonees.

2020: Donald Trump would like to pardon political sidekick Steve Bannon, corrupt and brutal Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio, and Ivanka Trump’s father-in-law Charles Kushner. But to do so, he must announce these possibilities by October 22—12 days before his extraordinarily close election race with Joe Biden. Trump, hoping to win re-election, drops these names from his final clemency list.

2024: Joe Biden is considering preemptive 11-year pardons for his son, Hunter, and five other family members, but he must announce these possibilities over two weeks prior to the nationwide elections. Political allies quietly tell him that if he does so, they will be forced to publicly condemn him. (Given his bitterness over the events of 2024, one can imagine several possible reactions from Biden.) Biden does announce that he is considering clemency for Leonard Peltier (who murdered two FBI agents), Michael Conahan (“cash-for-kids” judge), Rita Crundwell (Dixon, Illinois embezzler), and 37 of the 40 federal Death Row inmates (some of whom committed unspeakably brutal crimes). Law enforcement organizations demand that Peltier be dropped from consideration. Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro howls that Conahan must be dropped, and enraged Illinois Democrats demand that Crundwell be removed from consideration. Details of the Death Row killers’ deeds are on television 24/7 for three months, along with endless interviews with the aggrieved families. Perhaps Biden issues a tweet saying that some or all were never seriously under consideration.

2025: On his first day in office, Donald Trump announces his plans to pardon virtually every participant in the Capitol Riot of January 6, 2021. During the election campaign, he had pledged to pardon most of them, but members of his party—and especially now-Vice President Vance—had verbally carved out an exception for any rioters who had committed acts of violence on that day. Trump knows that if he discards that exception, some of his allies in the Republican Party and in the law enforcement community will break with him, embroiling the first three months of his administration in a needless, destructive controversy. He leaves those names off the list but, to save face, orders some notion of fair treatment of them while they await trial. He does pardon a large majority of J6 defendants, given that he had clearly promised for months that he would do so.

A constitutional amendment is always a heavy lift. One can offer massive arguments for and against stripping presidents of the power to issue pardons and commutations. But is there any persuasive reason to oppose this modest proposal—a 90-day Public Comment Period? The relevant question is who would oppose this idea—and why?

EXCUSE ME!!!

Senator Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson was an old-school politician of the best kind—smart, serious, and thoroughly decent. He likely would have made a superior president, but he had a serious drawback as a candidate—he was b … o … r … i … n … g. After Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon, Jackson heard a joke involving a conversation between Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford. Ford says something, Nixon responds (in the stereotypical Nixon voice) with “Pardon me?” and Ford said, “I already did that.” <rim shot> <sad trombone>

Jackson liked the joke and wanted to share it with an audience. In Jackson’s version, Ford said something. Nixon responded (in the stereotypical Nixon voice) with “Excuse me?” and Ford said, “I already did that.” <drummer and trombonist stand silent and confused>

Only cricket sounds came from the audience. Jackson couldn’t understand why the audience hadn’t appreciated such a funny joke, and turned to his aides in confusion. They had to explain the difference between “pardon me” and “excuse me” to him.

Preemptive pardon is utterly egregious, according to something deep in my bones.

Great article! I'd like to read something similar on executive orders.

One idea I have is a standard expiration date with no renewal, maybe a year. President has a year to convince the people and Congress its a good policy and get it passed.