NOTE: I’m posting excerpts from my not-yet-published book, “Fifty-Million-Dollar Baby: A Skeptic’s Eyes on Economics, Ethics, and Health.” The goal is to edit the manuscript in plain view—to seek your comments, corrections, and suggestions. This chapter is an edited and slightly expanded version of an earlier piece, “Genomics and the Shadowlands of Ethics,” published by InsideSources on April 25. 2018.

In health, ethics and economics often intertwine like DNA’s twin helices. Genomic technologies will likely transfigure the economics of healthcare, and ethicists will struggle to maintain a coherent framework of morality around the innovations.

A well-versed reader noted that I often write on eugenics and its present-day echoes and wondered how these writings play among people of faith. I responded that, over the years, my students have included religious Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, and others—and that their religious perspectives on eugenics always enriched the discussions in my classes. I also mentioned that I’m in the middle of reading a book, Preaching Eugenics: Religious Leaders and the American Eugenics Movement, by Christine Rosen. Finally, I mentioned an article that I wrote on the topic five years ago. This essay is a modest reworking of that piece.

Dor Yeshorim (דור ישרים) is an organization whose name comes from Psalm 112:2, and whose name means “upright generation.” After centuries of close quarters and endogamous marriage, a significant percentage of Jewish people of Northern European descent—“Ashkenazim”—carry genes associated with serious illnesses. (I am a product of those communities.) Perhaps the worst of these illnesses is infantile Tay-Sachs, a disorder that slowly shuts down a seemingly normal baby’s nervous system. Described by Christine Rosen in a 2003 article:

It begins innocuously enough. A six-month-old baby, once thriving and cheerful, begins reacting differently to normal sounds such as clapping hands or closing doors. Her parents notice that her limbs twitch and her muscles are not developing properly. She has trouble swallowing and shows signs of mental retardation. What they can’t see is her compromised brain tissue, which began degenerating when she was still in her mother’s womb. Soon their once-healthy child is in the grips of an overwhelming illness. As the deterioration intensifies, fatty deposits overwhelm the nerve cells in her brain, and she experiences seizures and paralysis. Bright cherry red spots appear on the retinas of her eyes, and she is rendered blind. Their daughter lapses into a vegetative state, and by the age of 3 or 4, she is dead, often of complications from pneumonia.

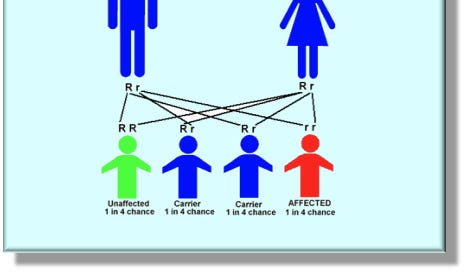

One of every 30 Ashkenazi Jews carries the Tay-Sachs gene. The disorder is autosomal recessive, meaning symptoms only present if the child inherits the gene from both parents — a 1-in-4 chance if both parents are carriers. So, in a random marriage between two Ashkenazim, each child has a 1-in-3,600 (1/30 x 1/30 x 1/4) chance of developing Tay-Sachs. This is the essence of the chart at the start of this essay.

In the deeply religious “Ultra-Orthodox” communities, concentrated in Brooklyn and Israel, marriages are still arranged by matchmakers (“shadchanim”), based on multiple criteria. For 40 years, an organization called Dor Yeshorim has tested almost all children in these communities for a panel of genetic disorders that includes Bloom syndrome, Canavan disease, Cystic fibrosis, Familial dysautonomia, Fanconi anemia (type C), Glycogen storage disease (type 1), Mucolipidosis type IV, Niemann–Pick disease, Spinal muscular atrophy, and Tay–Sachs. Tests for additional Ashkenazic diseases are available, as well as tests for genetic problems among Mediterranean (“Sephardic”) Jews.

Test results go into a database, with children identified only by personal identification numbers. To avoid stigmatization, those tested aren’t told whether they carry any problem genes. When a couple considers marriage, they exchange PINs and birthdates, so each can enter both in the Dor Yeshorim database and learn whether they share any of the problem genes. If they do, then marriage is deemed unadvisable. For the sake of privacy, Dor Yeshorim employees have no knowledge of who tests positive for any of the conditions, unless one or both seek genetic counseling from the organization.

For 40 years, Dor Yeshorim has enabled these communities to experience near-total success in preventing these illnesses. The practice, however, is controversial, because, among other things, some critics worry that it is a step in the direction of eugenics. The late Rabbi Moshe Dovid Tendler, professor of biology and expert in medical ethics at Yeshiva University, was a prominent critic of the program. He saw the program as “affirming eugenics” and said:

This is what happens when you have people with no scientific orientation who want to do good. The question arises, when do you stop? There are close to 90 genes you wouldn’t want to have. Will this lead to people showing each other computer print outs of their genetic conditions? We’ll never get married.

Eugenics sought to extend the selective breeding of agriculture and animal husbandry to human beings. The idea was that, armed with genetic data, we could breed superior human beings and eliminate problematic offspring.

A toxic blend of eugenics and cost-benefit analysis provided the logical underpinnings for the infamous Supreme Court case Buck v. Bell — which green-lit forcible sterilizations of tens of thousands of Americans. At its most extreme, eugenics handed the Nazis a scientific veneer to plaster over their mass extermination of millions. Nazi deputy leader Rudolf Hess declared, “National Socialism is nothing but applied biology.”

The debate over Dor Yeshorim has at times been intense among Jewish ethicists. After all, the Ultra-Orthodox communities that participate in the program are mostly descendants of those murdered because the Nazis judged them to be genetically undesirable.

The questions asked by Tendler and others is: Is Dor Yeshorim practicing an updated form of eugenics? If so, is that justifiable, given their families’ grim history in Europe? Answers don’t come easily. For the community involved, the absence of state coercion is a critical difference between then and now. To critics, that’s not enough.

Since few of us live in religious communities that rely on matchmakers, Dor Yeshorim may seem distant from our world. But could genetic testing services like 23andMe, combined with online dating services, bring Dor Yeshorim’s capabilities to the rest of us?

What should we think about Iceland’s near-elimination of Down Syndrome by genetic testing and abortion? Is it OK for prospective parents to choose their child’s gender in advance, raising the specter of the numerical imbalance already ripping at China’s social fabric? Do we want to precision-design our babies’ height, hair color, eye color, and IQ before birth? To what extent should we employ gene-editing to alter humans after they are born?

As science illuminates the hidden corners of the human genome, will we breed away the autism spectrum? And if so, how many Mozarts or Einsteins or Teslas might we discard in the process? In 2021, I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Temple Grandin, a renowned animal scientist, whose early life with autism was movingly depicted by Claire Danes in HBO’s feature film, Temple Grandin. Those podcasts are here and here.) Asked what would happen if autism were somehow eliminated, one of her standard answers is, “If you totally get rid of autism, you’d have nobody to fix your computer in the future.” She then rattles off lists of world-changers who were likely autistic—people like Steve Jobs.

Ultimately, the biggest question, and the most difficult to answer, is: Will future generations view our practices and our answers more charitably than we view the eugenicists’ illicit science?

Bob, Excellent piece. Well written and thought provoking. I have long believe that when our technical capabilities as humans outstrip our ethical development trouble is brewing. Science without an absolute moral compass gives us eugenics, genetic manipulation, mandated novel vaccines, gender affirmation therapy, including surgery, in children, cloning, and designer babies. It also gives us nuclear and biological weapons and gain of function research in viruse. I can see both sides of the argument regarding Dor Yeshorim. As a Christian, I know that we live in a fallen world and that mankind is subject to all sorts of physical imperfections that arise from that. My personal stance against abortion is mitigated, in part, precisely because of diseases like Tay Sachs as well as genetic anomalies like severe holoprosencephaly and anencephaly. I know of women, however, who, knowing their infant would be stillborn or die soon after birth with horrible anomalies, still carried them to term, delivered them, and loved them until they died. There are, indeed, angels among us. On the other hand, who would dare to judge someone in that situation who chose to abort? I had friends who had a high risk pregnancy because of the mother's age. Offered amniocentesis to check for any genetic or congenital problems they refused because it would not have changed their intent to keep the baby, regardless. I believe these situations and decisions are best kept between the parents and their doctor. Putting out into the public realm with politics and legislation coming into play serves little purpose and, at its worst, gives us things like eugenics. Rick

Bah. Dor Yeshorim is merely a source of information. If people are not compelled to use their services, and more importantly not compelled to abide by their judgment, there is no ethical problem. This is like arguing against warning signs on a highway.

But I also draw a distinction between diseases like Tay-Sachs, which has no upside, and autism and Down syndrome, which do.