When Healthcare Spending Isn't about Healthcare

And why price controls and insurance overhaul may not make much difference

If you’re not already a subscriber to Bastiat’s Window, please sign up for a free or paid subscription. (Paid really helps!) By all means, share the site and its articles with friends. This is an expanded version of my earlier article, “Maybe We’re Not in a Health Care Crisis?” published July 10, 2018 by InsideSources.

America’s healthcare debate revolves around two talking points, each of which blends some statistical truths with a cocktail of half-truths, non sequiturs, and outright falsehoods:

Talking point #1: On certain key dimensions—lifespan, infant mortality and so forth—America’s metrics underperform other developed countries and even some lesser-developed countries.

Talking point #2: Americans spend more on healthcare than any other country, both per capita and as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product.

We’ll dispense with the first point in this one brief paragraph. While America’s quality of care could be significantly better than it is, it’s still at or near the world’s pinnacle. The oft-cited comparisons with other countries rest mostly on one old, poorly executed, politically biased, wildly misused paper from the World Health Organization (WHO)—The World Health Report 2000. I won’t add a link to that paper as it should be considered NSFW (Not Suitable for Work)—assuming your work relies on accurate, meaningful data. For detailed explanations of the epic fails of that incessantly quoted study, see Glen Whitman’s “WHO's Fooling Who” and Scott Atlas’s “The Worst Study Ever?”

Now, we’ll move on to the second talking point. The United States does spend considerably more than any other country on healthcare. Observers on both the political left and right commonly recite this point as prima facie evidence that American healthcare is in crisis. They generally assume that salvation lies in some bundle of reforms to the healthcare system—particularly price controls or restructured health insurance—though they differ ferociously on which reforms.

But an alternative view—convincing, I believe—is that America’s heavy healthcare spending does not by itself constitute a crisis and is driven mostly by factors outside of healthcare. An earlier Bastiat’s Window piece, “From Strings to Sutures,” discussed how healthcare prices are influenced by prices in other sectors. This piece discusses how healthcare spending depends on facotrs outside of healthcare itself.

In particular, a 2017 article by software engineer and entrepreneur Peter Laakmann (“The Price is Right”) argues that Americans spend more on healthcare because, in effect, we’re wealthy spendthrifts (on everything)—not because of factors intrinsic to American healthcare. Laakmann’s arguments are related to a series of math-and-graph-laden posts at the RandomCriticalAnalysis (RCA) blog (e.g., “Why everything you have said about the determinants of health expenditure is wrong in one million charts: a response to Noah Smith”).

As these articles note, Americans spend a higher percentage of GDP on practically everything—for the simple reason that Americans save less and consume more than residents of other countries. Rather than stashing our income away for the future, we choose to buy things today—education, housing, travel, and, of course, healthcare. Plus, Americans have unusually high disposable income.

Laakmann and RCA argue that healthcare spending-to-GDP is not the ratio that we ought to look at. GDP includes government spending, investment, exports, etc. Laakmann/RCA argue (sensibly) that healthcare spending is a household decision, so the appropriate ratio to consider is healthcare spending as a percentage of household consumption—not GDP. And, it turns out, that ratio is only slightly higher for Americans than it is for other developed countries.

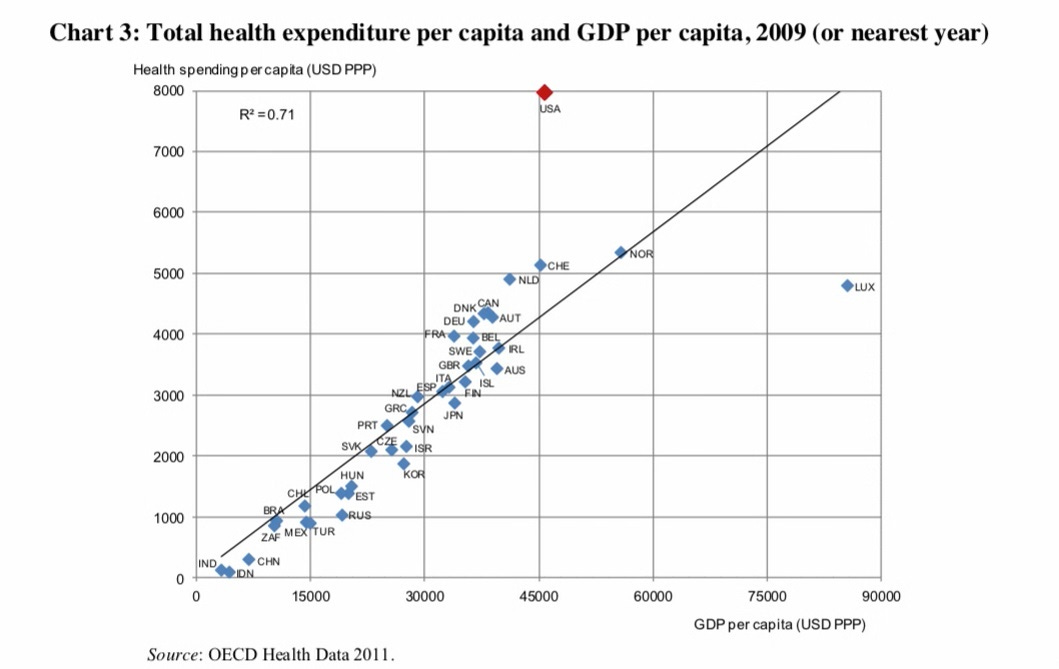

Let’s look at two of the many, many graphs included in the RCA blogpost referenced above. The first shows the relationship between per capita healthcare spending and per capita GDP. Notice that most countries are huddled around the upward-sloping line. The United States is the big exception, with the average American spending over $3,000 more than that line would suggest.

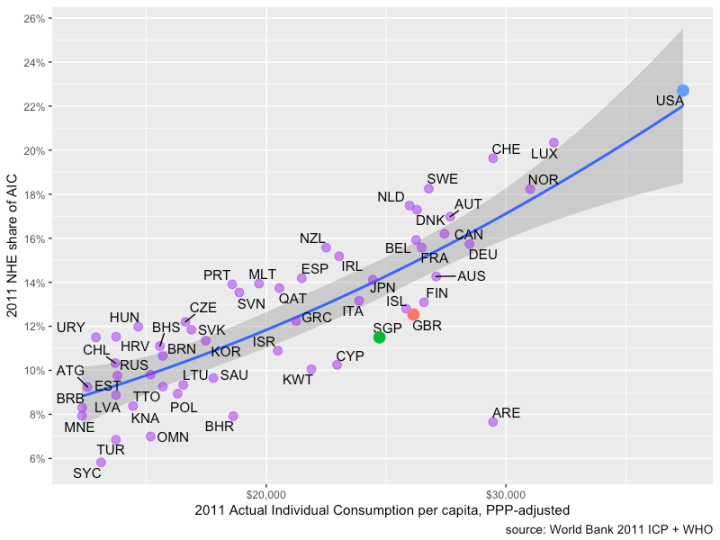

But in the next graph, RCA plots healthcare spending against “actual individual consumption” (AIC)—the income available to households (as opposed to governments or businesses). AIC also includes spending power that government programs hand over to households through health, education, and other entitlement programs. Here, the United States spends just about what you’d expect from the relationship implied by these other countries. As the article’s tongue-in-cheek title suggests, there are many, many more charts, but these two give a good idea why American healthcare spending may not be so wild, after all.

As the Laakmann/RCA articles also explain, compared with individuals in other developed countries, Americans have a massive amount of accumulated wealth—cash, securities, real estate, and so forth. So, we tend to buy things, including healthcare, using this extra reserve. Here’s a small analogy to illustrate the point of all this:

Picture two men—Smith and Jones. Both earn $1,000 per week after taxes and benefits. Smith doesn’t save a dime. Jones puts $100 in a savings account each week. Then, the two go to restaurants every night. Each week, Smith spends $200 on restaurants and $800 on everything else. Jones spends $180 on restaurants and $720 on everything else.

Now, a social scientist studies their behavior. He notes that Smith goes to ritzier restaurants. This, he concludes, is why Smith spends so much. “If we can get Smith to go to the same downscale restaurants where Jones dines, his expenditures will drop to Jones’s level.”

But this misses the key factor. Smith’s bigger tab stems not so much from where he eats, but more from how much he allots each week to eating out. Compared with Jones, Smith has an extra $100 to blow each week on consumption. Smith spends 20 per cent of his income on dining out, while Jones only spends 18 percent. But as a percentage of consumption, both men spend an identical 20 percent ($200 of $1,000 for Smith, $180 of $900 for Jones).

Force Smith to dine at Jones’ cheaper restaurant, and he’ll likely just order more expensive items and drink better liquor than Jones does.

Summing up: The ratio of healthcare spending to GDP is higher in America than in just about any other country per capita and as a proportion of GDP. Conventional wisdom, likely mistaken, holds that this high ratio constitutes a crisis, proves that something is out of whack with American healthcare, and is best mitigated by some combination of price controls and insurance reforms. An alternative viewpoint is that the high healthcare spending-to-GDP ratio results more from Americans’ unusually high disposable income, propensity to consume, and accumulated wealth; if so, this would suggest that conventional healthcare reforms—insurance restructuring and price controls, will likely fail to reduce spending by much.

This is not a plea for policy nihilism. Perhaps Americans’ low saving rate does constitute a brewing crisis. But if so, doodling around with the healthcare system isn’t likely to change that. No doubt, Americans could get more health from their healthcare spending than they do—but that would mean better spending, and not necessarily to lower spending. Perhaps reforms would best be aimed at improving the quality of care and finding more efficient ways of treating patients. That might not reduce spending, but it just might make us healthier and happier.

LAGNIAPPE

The article above is about numbers (in terms of dollars) not always being quite what they seem, so here’s a musical work I composed in 2015 where the numbers (in terms of rhythms) are not always quite what they seem. This polyrhythmic piece combines the style of a Renaissance madrigal with elements of jazz, blues, and 20th century classical music. My wife’s painting similarly combines Renaissance art with contemporary abstraction. As always, headphones help.

Your first paragraph is a great distillation of the debate, and the post keeps climbing from there. I would add that healthcare is expensive because the healthcare workforce makes up about 14% of the total US workforce and the average wages for most occupations is significantly higher than the average. But we also gain something other systems don’t have, and that is responsiveness in many parts of the system (I know - there are horror stories aplenty, but there are also scores of stories where rapid actions through the system saved lives).'We typically are not kept waiting for critical procedures like one hears about in Canada and the UK. There is no question that the system needs improvement, but that can happen only if we are willing to allow new ideas to be tried rather than stifled by massive bureaucracy in the public and private sectors.

Great piece Robert. I've always been amazed when people felt that they'd get better care in Cuba. The care here is complicated, and sometimes expensive, but remarkable.