When Saving a Child's Life for Free is Bad News

NPR's Glass-Half-Empty Take on Lifesaving Medical Services. [Plus, a place where medical bills are transparent and predictable.]

Paid subscriptions help keep Bastiat’s Window going. Free subscriptions are deeply appreciated, too. If you enjoy this piece, please click “share” and pass it along. This is a lightly edited version of an article published by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in July 2019.

I’ve inserted as footnotes a few comments sent to me last week by an emergency physician, Edwin Leap, who kindly read this piece in advance. Dr. Leap publishes his own Substack—Life and Limb—which I highly recommend. In response to my recent “A Quiet Bluegrass Genocide,” Edwin introduced himself to me as follows: “I was born and raised in WV, as was my wife, daughter of a coal miner. I have practiced emergency medicine in the rural South for decades, and what I see now is more of the same. I'm currently working in Southern WV. Between poverty, the mental health crisis, methamphetamine and fentanyl, Appalachia seems abandoned.” His Life and Limb essays are soulful, informative, and beautifully written.

American healthcare doesn’t always inspire sympathy, but sometimes, what the press and others portray as disturbing is actually inspiring—or at least justifiable.

In April 2019, National Public Radio (NPR) and Kaiser Health News (KHN) ran a story describing the monstrous medical bill a family received after their child was bitten at summer camp by a snake—likely a copperhead—and airlifted to a hospital, where doctors administered four vials of the antivenin (a.k.a., antivenom) CroFab. The piece lambasted the air ambulance service, the drug company, the hospital, and the health insurer—and blamed the high prices on monopoly power and lack of price controls on drugs.

Websites worldwide picked up the story, variously describing the bill as “whopping,” “jaw-dropping,” and the work of “serpent profiteers.” KHN’s slightly edited version subtitled the story, “The snake struck a 9-year-old hiker at dusk on a nature trail. The outrageous bills struck her parents a few weeks later.”

NPR titled its piece, “Summer Bummer: A Young Camper's $142,938 Snakebite,” but the title could just as easily have been, “Summer Miracle: Helicopter, Hospital, and Rare Serum Save 9-Year-Old’s Life—for Free.” As we learn near the end of the story, the family’s health insurer negotiated charges down to $107,863.33 and paid that amount; the camp’s insurer paid $7,286.34 to cover the deductible and coinsurance the parents would otherwise have paid. According to the report, the family paid zero.

So, the story seems to have two points. First, that it’s awful that a family received a terrifyingly large bill and had to wait nervously until insurers wiped the slate clean. Second, that the helicopter and antivenin cost far more than they should. (To clarify, these were the perceptions expressed in the article, not my perceptions.)

I have no quarrel with the article’s first point. It’s easy to sympathize with this family receiving a $142,938 statement and agonizing over it until it went away. Similar mailings spooked my parents during their late-life illnesses. Statements often said, “This is not a bill,” but those words hardly calmed our nerves.

So how about one simple, costless reform that could instantly reduce Americans’ healthcare angst: don’t send patients any billing statements until insurers and providers have concluded their negotiations. And when you do, put the bottom line right up top. If this family had received only one statement, reading, “You owe $0, but your insurer paid $107,863.33 and the camp’s insurer paid $7,286.34,” would this have been a news story?

It probably would have, since much of the story attempts to build the case that the costs were excessive, regardless of who paid. But, though there may be some merit to that second point, the story doesn’t successfully make that argument, either. Let’s unpack the numbers.

Were The Costs Excessive?

NPR describes the nine-year-old’s terrible day: deadly snakebite at summer camp, desperate helicopter flight to the trauma center, four vials of antivenin, recovery and departure from the hospital a day later. Weeks later, the family received bills totaling $142,938, including $55,577.64 for the helicopter and $67,957 for the antivenin. The remainder consisted of physician, hospital, and ground ambulance charges.

The broadcast’s financial analysis came from Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal, a non-practicing physician and KHN’s editor-in-chief. She said a much cheaper alternative is available in Mexico and offered her ideas on why the charges were so high in this case:

“We’ve talked about high air ambulance prices before. . . When your kid gets a poisonous snakebite, they’ll die without rapid treatment, so you’re vulnerable to financial extortion. . . [T]he drugmaker in this case had a monopoly on the product. . . The hospital has a captive audience here and can mark up with abandon. . . When your insurer and your company jumps in to save you from these extortionate bills, . . . premiums in your company are likely to go up the next year.”

This narrative—”financial extortion!” “monopoly!” “captive audience!” “extortionate!”—clearly implies that the costs were excessive and abusive. From Rosenthal’s quotes, we can discern four culprits—the helicopter company, the drug manufacturer, the hospital, and the insurers. Let’s examine each:

The Helicopter Company

The story suggests that the child might have died without the helicopter[fn1]. But helicopters and supporting infrastructure aren’t cheap. A Managed Care article, “Air Ambulance Turbulence: Consolidation, Cost Shifting, and Surprise Billing,” explores whether helicopter costs are excessive. Their answer is, effectively, “maybe yes, maybe no.” At the very least, the manpower needs are eye-opening:

“Keeping a single air ambulance helicopter ready 24 hours a day requires 13 people—four pilots, four nurses, four paramedics, and a mechanic, a big national operator told GAO. The agency said based on cost figures from eight air transport providers, the average cost per flight in 2016 ranged from $6,000 to $13,000.”

Why was the cost so much higher in this case? Here are two conjectures: perhaps the 160-mile roundtrip was much farther and more time-consuming than average flights. Or perhaps air ambulance flights around Evansville, Indiana are infrequent, requiring the company to spread fixed costs over relatively few patients. The helicopter company’s explanation would be interesting[fn2].

The Drug Manufacturer

Part of the antivenin charge is the enormous cost of developing any drug and obtaining Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. That process can take more than a decade and can cost over $2.5 billion. Plus, not many people suffer venomous snakebites. BTG (CroFab’s manufacturer) said that as of 2019, the drug had been used on 50,000 patients over 15 years. $2.5 billion (if that’s what BTG spent) spread over 50,000 cases is $50,000 per patient—just to cover research and development costs.

No doubt, the company had sold many times that number of vials to stock pharmacy shelves. (Its shelf life is only 30 months.) This certainly helps explain why CroFab’s wholesale price was $3,200 per vial—far below that conjectural $50,000 figure.

The Hospital

NPR noted that hospitals usually charge patients around $16,000 for four vials of CroFab. The story never suggested that BTG charged the hospital, St. Vincent Evansville, more than the usual wholesale price. The hospital, it seems, was primarily responsible for the much higher charge. What can explain that sort of markup?

Let’s assume hospital pharmacies buy enough CroFab to cover the manufacturer’s development, approval, and production costs. But in 15 years, they had only been reimbursed for those vials that went to 50,000 actual snakebite patients. If every patient used four vials, for example, that would total only $640 million—far less than a typical drug’s development and approval costs. Who pays the difference?

Perhaps St. Vincent Evansville rolled the costs of unused vials onto the bills of snakebite victims or onto the bills of patients who’ve never been near a venomous snake. (This hints at a possible answer to the question, “Why does some hospital charge $50 for an aspirin?”) Hospital charges are also mires of cross-subsidies, so perhaps St. Vincent’s accounting system rolls other costs—personnel, equipment, administration, and charity care—into the antivenin charge. This is only my speculation, but it would be nice to ask the hospital whether that’s the case.

Then there’s the fact that the “charges” patients initially receive are mostly accounting fictions that no one will ever pay. In fact, the insurer here negotiated the CroFab price down to $44,092.87. For those who blame American healthcare’s ills on “profits” (like the website that blamed “serpent profiteers”), note that that St. Vincent Evansville is a not-for-profit, religious-affiliated hospital.

The bottom line is that the billions it takes to bring a drug like CroFab to market will ultimately come from someone’s pocket—patients, providers, insurers, or taxpayers. Perhaps the $44,092.87 charge here was excessive, but the story lacks sufficient information to warrant that conclusion.

The Insurers

When critics of American healthcare round up the usual suspects, insurers are often the first in the squad car. In this story, however, insurers negotiated the bills downward and, according to the story, paid every penny. The story notes that large charges, such as the one described here, cause insurance premiums to rise. That’s true, but again, someone—patients, providers, insurers, taxpayers—have to pay.

Now, let’s look at three questions that the NPR story did not address:

[1] What would happen if we didn’t pay “outrageous” amounts to air ambulance services?

In 2009, actress Natasha Richardson died after a skiing accident in Canada, where provincial governments pays for healthcare. According to an ABC News report at the time:

“The province of Quebec lacks a medical helicopter system, common in the United States and other parts of Canada, to airlift stricken patients to major trauma centers. Montreal's top head trauma doctor said Friday that may have played a role in Richardson's death.”

The Globe and Mail added:

“The Quebec government is making no excuses for the lack of a helicopter air ambulance service to transport trauma patients such as actress Natasha Richardson. . . Purchasing a helicopter ambulance is not a priority and there are no plans to acquire one, a government spokeswoman said yesterday.”

So, the good news is that, in 2009, no one in Quebec faced an unexpected $55,577.64 air ambulance bill. But the bad news is that if your life depended on such a service, you’d be dead.

[2] NPR’s Rosenthal suggested, “This kind of case is exactly why other countries do regulate drug prices.” But would such a policy yield cheaper antivenin?

Rosenthal said a much-cheaper drug was available in Mexico, but this seems irrelevant to the story. Hospitals can only use those drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). According to this story, CroFab was the only FDA-approved antivenin when this child was bitten. NPR said a second serum, Anavip, has since gained FDA approval—but not for copperhead bites.

So, maybe Anavip wouldn’t have saved this the child’s life.

Or maybe Anavip would have saved her, but the FDA had been sluggish in granting approval. My friend and erstwhile colleague, Alex Tabarrok, once wrote:

“the FDA has an incentive to delay the introduction of new drugs because approving a bad drug. . . has more severe consequences for the FDA than does failing to approve a good drug. . . In the former case at least some victims are identifiable and the New York Times writes stories about them and how they died because the FDA failed. In the latter case, when the FDA fails to approve a good drug, people die but the bodies are buried in an invisible graveyard.”

Or maybe the FDA has been prompt and efficient, but Anavip’s manufacturer hasn’t made an adequate case.

Or maybe the FDA and the manufacturers of Anavip and CroFab have done all they can, and the high cost simply reflects the fact that producing antivenin is an expensive endeavor. NPR’s account didn’t provide any grounds for choosing among these conjectures.

The U.S. is the world’s premier pharmaceutical developer in part because under our less-regulated price system, manufacturers stand a chance of recouping costs. To a considerable extent, other countries free ride on the higher prices Americans pay. If the federal government mandates that our prices drop to European or Canadian levels, will we get cheaper antivenin, or will manufacturers simply stop developing drugs like CroFab or Anavip? (The absence of air ambulances in Quebec hints at an unpleasant answer.)

[3] Are there, in fact, unlucky families who receive gigantic medical bills for snakebites and actually have to pay that amount?

Rosenthal said, “These guys were lucky.” At the time of the story, both parents worked at Indiana University Bloomington. Though unmentioned in the story, the mother was also an elected official and two-time congressional nominee. Almost certainly, their jobs provided them with top-of-the-line health insurance. Since 1983, I’ve enjoyed first-class health insurance through employer-sponsored plans, as well. In fact, a large percentage of Americans are similarly “lucky.”

But some Americans aren’t so lucky. Some lack insurance, and some have lower-quality insurance. While federal law gives all Americans guaranteed access to emergency care, regardless of ability to pay, it would be interesting to know whether others in Bloomington, Indiana, are “unlucky” and would have been financially destroyed by the same copperhead bite at the same place. Does that happen? If so, that’s a really powerful story. But it’s not one that made the NPR story[fn3].

Conclusion

NPR raised excellent questions but painted an exceedingly dark impression of American healthcare. But, a different spin on the story’s facts could have put American healthcare in extraordinarily favorable light.

In the glass-half-full version, America is a place where: (1) For-profit corporations spend vast sums to develop lifesaving drugs that very few people will ever need; (2) Helicopters stand ready at all hours to transport grievously wounded people; (3) Hospitals are perpetually ready to provide labor, resources, and know-how to save people from the jaws of death; and (4) insurance companies sometimes pay every cent of the cost of such miracles.

For those who imagine that savings lie in price controls and government financing, picture yourself, grievously injured, atop a mountain in Quebec.

fn1: From Edwin Leap, MD: “copperhead bites are almost never fatal but can cause severe tissue damage depending on the amount of envenomation and other factors. Most deaths in the US are from rattlesnakes. Which are, fortunately, more reclusive and less ill tempered. And they come with that handy alarm system. Copperheads are jerks.”

fn2: Also from Dr. Leap: “For air you have to dispatch, warm up the aircraft, load crew, take off, travel, land, turn it off, egress crew, go to patient, assess, maybe stabilize, load patient, load crew, restart, etc. "Hot loads" [tending to the patient while the helicopter idles] do happen but are potentially dangerous. I once nearly walked into a tail rotor as a resident when I was going out the rear clamshell doors on a night flight.”

fn3: A colleague of Dr. Leap’s added: “I see so many patients stuck with the cost of out of network services and some have no out of network benefits with policy they purchased. Docs and other providers have no idea what is billed or covered. The whole system works in a way where the right hand has no idea what the left hand is doing. The patients are often stuck with the bill through no fault of their own. The system is broken.”

Lagniappe

Surgery Center of Oklahoma: No-Surprises Billing

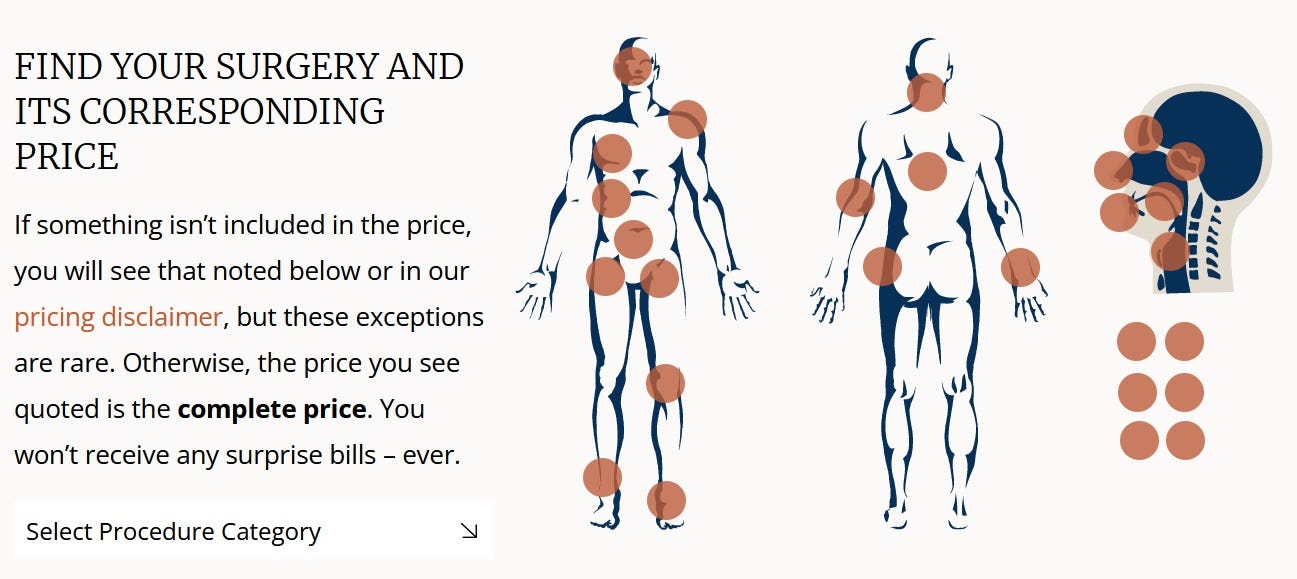

The story above focuses on two unpleasant aspects of American medicine—high costs and surprise billing—and illustrates these points with the snakebite patient’s 6-page bill. In the 1990s, Dr. Keith Smith and his colleagues founded the Surgery Center of Oklahoma (SCO) to combat both costs and surprises. SCO’s bills look like the $6,349.00 bill shown here:

At SCO, patients don’t receive the usual pages and pages of inexplicable codes and charges. Just one number, all-inclusive and known in advance. To learn the exact prices of hundreds of surgical procedures at SCO, just go to their user-friendly website and click on the part of your body that needs repair and the specific repair needed:

To understand how SCO does all of these, read my 2016 article, “Transparent Health Care Pricing — Keith Smith and the Surgery Center of Oklahoma.” You can also listen to or read the text of my 2021, podcast conversation with Keith at, “Fortress and Frontier: Price Transparency in Healthcare.” You’ll hear of the ferocious opposition that SCO faced from established hospitals and insurers. (You’ll also learn how Keith nearly became a concert pianist instead of a doctor.)

Just to recap:

1) “Statements” are not bills.

2) “Charges” are not payment due. They usually contain a huge amount of markup and gobbledygook.

3) Payment is based on negotiated rates. No one pays the “price” of a car.

4) Nonprofit hospitals often greatly reduce or write off large amounts due — especially for children. They consider it charity care.

Enjoyable read--and a couple of points:

Pharma companies typically do not price drugs to recoup sunk costs. They price drugs to fund the next new drug. BTG Pharmaceuticals develops drugs that treat rare, emergent problems such as poisoning from other drugs (eg, digoxin) and exposure to high doses of radiation. As you say, thank God a company has developed such treatments.

I wonder if the hospital had antivenin sitting around. Perhaps--copperheads are not rare in Indiana. But perhaps not--many rarely used drugs can be obtained very quickly from wholesalers.

Air ambulances: I run in the Sierra Nevadas and other mountain areas. Air ambulance insurance is both cheap and essential. Rescue costs are $45-60,000. This isn't a hop from one hospital to another.

Drug price controls: Tom Sowell says always ask "and then what?" When no one can make a profit on a drug, the drug doesn't get made. Some vital meds --such as chemo drugs-- are in short supply, in part because the reimbursement for them is not profitable. Imagine that. 2nd and 3rd order consequences.

Thanks for the article.