When Sterilization Was Dogma: Why the Eugenics Movement is Relevant Today

Ted Balaker interviews Robert Graboyes on groupthink in public health

This is my 100th post since Bastiat’s Window went live last August 17! Social media can be a poisonous hellscape, but Substack readers seem to be the cream of the crop. The hundreds of comments posted here have been uniformly interesting and thoughtful. Thanks!

Today, documentary director/producer Ted Balaker inverviews me on eugenics at his Shiny Herd substack. In Ted’s 2015 documentary, Can We Take a Joke?, Comedians Penn Gillette, Gilbert Gottfried, Lisa Lampanelli; social commentators Jonathan Rauch and Greg Lukianoff, and others explore the cancel culture that menaces comedians and humorists. His 2017 Little Pink House re-enacts Susette Kelo’s failed effort to defend her Connecticut home (and those of her neighbors) from eminent domain. His forthcoming The Coddling of the American Mind, will explore the retreat of free speech from contemporary discourse.

What follows is Ted Balaker’s interview with me, originally published at Balaker’s Shiny Herd substack—a terrific publication focused on free expression and avoidance of groupthink.

They were forced to undergo hysterectomies. Their tubes were tied and they were given vasectomies, sometimes without anesthesia.

They were preyed on, not by serial criminals or deranged cults, but by the most powerful people in the land, by people with impressive credentials and positions, by leaders in public health and government who were convinced they were on the side of science and progress.

More than 70,000 Americans were victimized by America’s eugenics movement, which peaked in the 1920s but lingered into the 2010s.

“Eugenicists sought to ‘improve’ the human species in the same way that one would improve cattle or soybeans—and using basically the same techniques.”

So says Robert F. Graboyes, an economist, journalist, musician and scholar of the largely unknown eugenics movement. He’s also the man behind the endlessly insightful substack, Bastiat’s Window, where he writes on the seen and the unseen in economics, ethics, health, technology, and culture. (It’s one of my favorite reads.)

Graboyes taught at five universities, including 48 semester-long graduate courses in health economics. He challenged his students—medical professionals such as doctors, nurses, therapists, and administrators—to resist groupthink.

Perhaps his most effective method was to teach them about the eugenics movement, and his classes were usually his students' first substantive exposure to the topic.

Graboyes notes that eugenics was the dogma of the early 20th century—speaking out against it meant risking your job or reputation. He says the movement did so much damage because of “eugenicists’ lack of skepticism and their brutal intolerance of dissent.”

Below I ask Graboyes about the American eugenics movement’s influence on Nazi Germany, which public figures dared to speak out, and why the eugenics movement is relevant today.

What is most important for people to know about the eugenics movement?

Eugenics wasn’t the brainchild of sadistic charlatans. Its founders also invented mathematical statistics—the core of modern science. Eugenicists were driven by hubristic humanitarianism.

What types of people were sterilized?

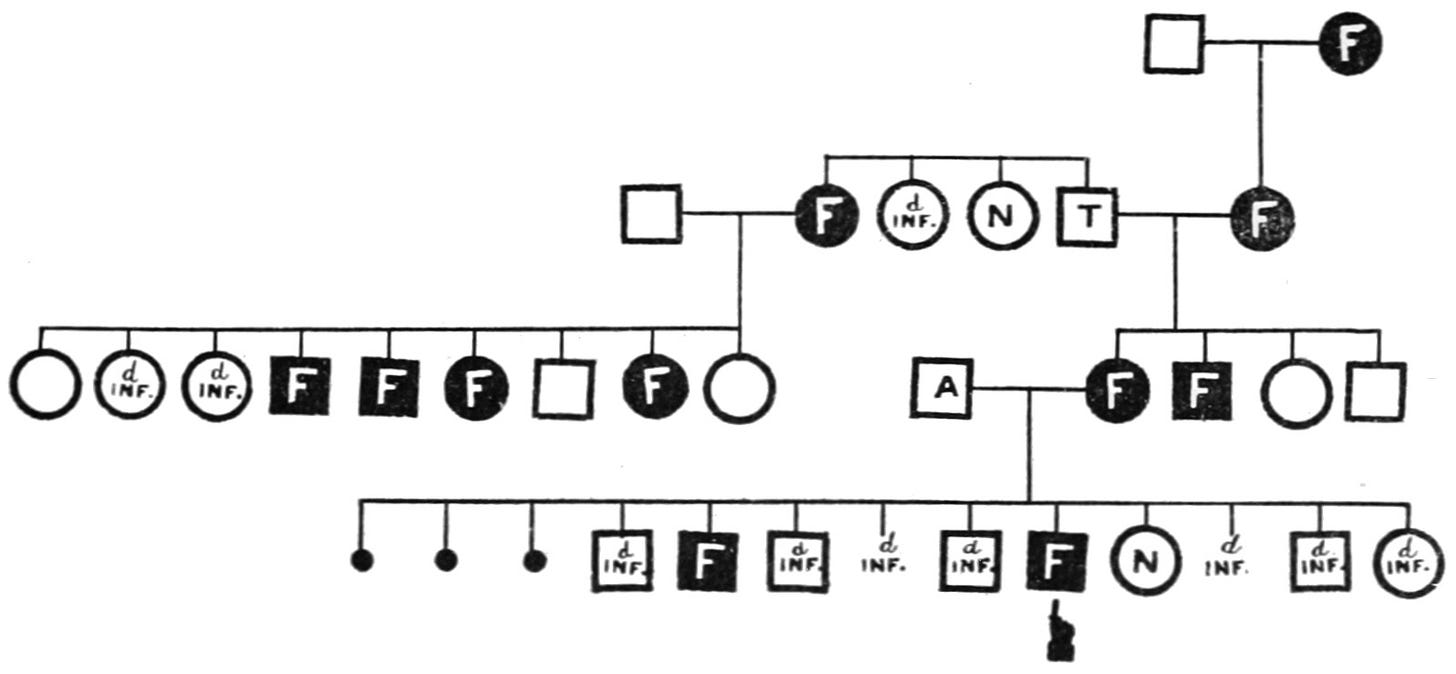

Eugenics differed from place to place. In my home state, arguably the epicenter of American eugenics, the Virginia Sterilization Act of 1924 applied to persons:

"afflicted with hereditary forms of insanity that are recurrent, idiocy, imbecility, feeble-mindedness or epilepsy.”

In 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Virginia law in Buck v. Bell. That case tells you lots about who was sterilized: Carrie Buck’s mother was a suspected prostitute. Placed in a foster home, Carrie was raped and impregnated by the foster parents’ nephew.

A social worker testified, without foundation, that there was “something peculiar” about Carrie’s infant daughter. Harry Laughlin, Superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office in Cold Spring Harbor, NY, never met Carrie, but testified that the Bucks were of:

“the shiftless, ignorant, and worthless class of anti-social whites of the South.”

Convinced by these arguments, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., wrote:

“It is better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes …Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

A 1905 Court ruling okayed a $5 fine (c.$170 in 2023 dollars) on those refusing smallpox vaccination. Twenty-two years later, eight justices said that ruling also justified state-mandated hysterectomies and vasectomies on children.

Virginia sterilized individuals who had stolen things, who had alcoholic or criminal relatives, who lacked education. They sterilized children who fled abusive households.

Public health officials decided who was “socially inadequate.” Around 8,300 individuals were sterilized before the program ended in 1979.

You can get a strikingly comprehensive answer to this question by watching a 49-minute documentary called The Lynchburg Story. I used the video in teaching for decades and have seen it at least 100 times.

It still never fails to fascinate and horrify me. (Note: There’s a buzz for the first couple of minutes, and midway through, the screen briefly goes black.)

How did race factor in?

Racial factors varied across states. Virginia sterilized plenty of African Americans, but paradoxically, the Virginia government’s century-long obsession with segregation may have worked slightly in the interests of African Americans. White supremacist elites were mostly interested in purifying their own race.

North Carolina sterilizations were tilted more toward African Americans, largely because of the efforts of public health official Wallace Kuralt—a highly respected progressive—who strongly influenced the North Carolina Board of Eugenics (which existed till 1977).

California performed coerced sterilizations on female prison inmates into the 2010s. The victims were heavily African American and Hispanic.

Some of Graboyes’ previous writings on eugenics at Bastiat’s Window include: The Briar and the Rose, Blessed Skepticism, No, I'm Not a Eugenicist, Eugenics Isn't Just History, When Genomics Meets Eugenics, Blessed Chesterton, and Lessons from the Tuskegee Study.

What were the eugenicists’ main goals and how did they frame them as progress?

In Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era, economic historian Thomas C. Leonard told:

“the story of the progressive scholars and activists who enlisted in the Progressive Era crusade to dismantle laissez-faire and remake American economic life through the agency of an administrative state.”

Bradley W. Hart’s review of Leonard’s book says:

“Immigration restriction, compulsory sterilization laws, and bans on interracial marriage all grew out of the eugenic movement's ideas and legislative successes in the early twentieth century. Leonard examines how debates over minimum wage laws and industrial conditions were also influenced by its tenets, often as a way for reformers to distinguish ‘worthy’ workers from the ‘unemployable.’ Eugenics thus became a key intellectual tool for Progressives in their arguments for the regulation of society to increase efficiency and a key criterion in determining which individuals were deserving of state assistance and which were not.”

How did groupthink perpetuate eugenics?

From Leonard:

“In the first three decades of the twentieth century, eugenic ideas were politically influential, culturally fashionable, and scientifically mainstream. The elite sprinkled their conversations with eugenic concerns to signal their au courant high-mindedness. As [University of Wisconsin scholar Edwin] Ross put it, interest in eugenics was almost ‘a perfect index of one's breadth of outlook and unselfish concern for the future of our race.’”

Enthusiasts included Winston Churchill, W.E.B. DuBois, Margaret Sanger, Alexander Graham Bell, Helen Keller. John Maynard Keynes, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, H.G. Wells, D. H. Lawrence, and countless others.

Eugenics was taught in medical schools. The 1925 Scopes Monkey Trial is usually presented as a triumph of science, modernity, and free discourse over religious censorship.

But consider the high school textbook that got John Scopes arrested:

“A Civic Biology was one of the most widely used Biology Textbooks of its time. John T. Scopes used this edition of the Text to teach evolution prior to the ‘Monkey Trial’ in Dayton, Tennessee, in 1925. Hunter's Text espoused the belief in a racial hierarchy of the world's population. White, Anglo-Saxons were situated at the superior position in this hierarchy and Africans were at the bottom. Such beliefs fueled the Eugenics movement which discouraged reproduction among the inferior races.”

Eugenics became a staple at county and state fairs, which held “Fitter Family” and “Better Baby” contests. From one “Better Babies” poster (shown at the beginning of this article):

“American women have started a revolution by judging babies at the State Fairs just as carefully as hogs are judged. They measure and test babies and award prizes to the healthiest and brightest. And now a National Campaign for ‘Better Babies’ is sweeping across the country.”

Explain how widespread support for eugenics was among the public health community. Why was it so appealing to so many?

As I wrote a couple of years ago:

Legal historian Paul Lombardo has documented how, in the interest of “population health,” 20th-century public health was complicit not only in forced sterilizations, but also in bans on interracial marriage, bans on marriage between disabled Americans and deportations of immigrants who failed spurious IQ tests. For forty years, the U.S. Public Health Service and the Centers for Disease Control conducted the horrific Tuskegee syphilis study on African American men. The common thread is that public health officials have been willing to exert damaging control over individuals in the name of collective goals and to feign authority in areas where they are mere dilettantes.

Across the United States, public health workers were front-line troops for eugenics. NPR’s Julie Rose noted that in North Carolina, a Human Betterment League, funded by wealthy industrialists, published promotional materials, including a brochure asserting that:

"The job of parenthood is too much to expect of feebleminded men and women … North Carolina offers its citizens protection in the form of selective sterilization."

Rose added:

“The Human Betterment League made social workers and doctors and public officials feel like humanitarian heroes for sterilizing people.”

What happened to dissenters who spoke out against eugenics?

Again, from Leonard:

“Until the late 1920s, American geneticists supported eugenics or kept their reservations private while welcoming the funding and publicity eugenics generated.”

Leonard noted that biologist Raymond Pearl, a one-time eugenicist, publicly repudiated eugenics in H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury.

As a result, Harvard withdrew a job offer it had extended to him. One can plumb the depth of support for eugenics in American academe from Harvard Magazine’s “Harvard’s Eugenic Era”:

“Harvard administrators, faculty members, and alumni were at the forefront of American eugenics—founding eugenics organizations, writing academic and popular eugenics articles, and lobbying government to enact eugenics laws. And for many years, scarcely any significant Harvard voices, if any at all, were raised against it.”

Major funders of scientific research, including the Carnegie Institution, Rockefeller Foundation, and the Harriman family, were firmly in the pro-eugenics camp. A National Library of Medicine article noted that:

“Publications were bolstered by the research pouring out of institutes for the study of eugenics or ‘race biology.’”

It’s a big mistake to call eugenics a “pseudoscience.” It was hard, mainstream science whose debate was suffocated by ruthlessly enforced orthodoxy.

You and other scholars of the eugenics movement regard it as part of the progressive movement. In what way was it progressive?

“Progressivism,” from the early 20th century to today, has always been more about means than ends. It is not synonymous with “unbiased,” “caring,” or “broad-minded.”

The various waves of progressivism over the past century have shared the following qualities: great faith in credentialed experts, enthusiastic use of state power to effect social change, and a willingness to subordinate individual liberties beneath collective good.

The Encyclopedia Virginia described Dr. Joseph DeJarnette, who performed hundreds of sterilizations at Western State Hospital, as follows:

“In 1934 he implored the [state legislature] to broaden the scope of Virginia’s sterilization law; ‘the Germans,’ he complained, ‘are beating us at our own game and are more progressive than we are.’ DeJarnette never wavered in his advocacy of eugenics, not even after the revelation of the Nazi Holocaust, and he often recited or appended to his publications on eugenic sterilization a poem that he had composed, ‘Mendel’s Law: A Plea for a Better Race of Men.’”

How did the American eugenics movement influence totalitarianism abroad?

A couple of examples: Madison Grant, a friend of Theodore Roosevelt and Herbert Hoover, was a key figure in establishing the Bronx Zoo, Denali National Park, Glacier National Park, the Save the Redwoods League, and the whole idea of wildlife conservation; he also wrote The Passing of the Great Race, which Hitler would term “My Bible.”

Harry Laughlin accepted an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg in 1936 for his contributions to the “science of racial cleansing.” At the post-World War II Nuremburg Trials, several Nazi officials defended their eugenic policies by citing U.S. sterilization laws and Buck v. Bell.

Were there any prominent people or organizations that spoke out against the eugenics movement? Did their criticisms have any impact on the eventual downfall of eugenics?

British writer G. K. Chesterton stands out as perhaps the fiercest opponent of the idea. In 1922, he published, Eugenics and Other Evils: An Argument Against the Scientifically Organized State. Anthropologist Franz Boas spoke out against eugenics in 1916.

Until the late 1930s, relatively few other public intellectuals joined in the opposition. The Catholic Church was perhaps the most prominent organization in opposition. In 1930, Pope Pius XI condemned sterilization laws, writing:

"Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."

The Eugenics Record Office was financed by powerful organizations, including the Rockefeller Foundation and Carnegie Institution. In the mid-1930s, opinion began to change.

Carnegie investigators found the office’s work shoddy and demanded that they cease work. In 1939, Carnegie’s new president, Vannevar Bush, forced Laughlin to retire; the office was soon shuttered.

Three things really sent eugenics into hiding. Nazi Germany provided the most extreme example of where eugenics could take you. During the Great Depression, people who had been financially comfortable and had considered poverty a condition of genetically inferior people, suddenly found themselves unemployed, broke, and desperate

And some courageous journalists late in the 20th century revealed the horrors. “Truth will out,” Shakespeare wrote, but his maxim offers no timeframe.

Today the eugenics movement strikes us as barbaric, and it might be tempting for us modern people to think we couldn’t fall prey to such madness. But you say that would be a mistake. Why?

Consider COVID. Those who disagreed with or even politely questioned public health orthodoxies were pilloried, smeared, threatened, censored. Social media platforms shut down debate and labeled reasonable questions and discussions as “disinformation.”

It turns out that one of the more salubrious activities during the pandemic was going to a beach, getting exercise, and enjoying the sunshine and breezes. In California, authorities arrested a lone paddle-boarder for being alone on the water, rather than cowering in his apartment.

In Florida, which wisely kept its beaches open, a showboat lawyer strolled the beaches dressed as the Grim Reaper, attempting to shame those who were partaking of said sun and wind and sand and water.

At a time when people were prohibited from visiting their dying parents in the hospitals or holding outdoor funerals, a phalanx of public health officials decided that it was the duty of Americans to congregate by the tens of thousands in the streets for mass political marches.

A credulous and servile press relentlessly lionized all these actions and vilified those who disagreed. And we can see this same dynamic playing out on practically every other hot-button issue afloat today.

How can we guard against future episodes of destructive groupthink?

I wish I had an easy answer. I have always told my students that the most important quality that can acquire is skepticism. “Question everything.”

For 19 years, I taught the economics of healthcare to mid-career medical professionals and others at five universities. I always included a multiweek segment on eugenics. Most knew little or nothing about the subject. At the end of one such class, one doctor said in class:

“You’ve now destroyed everything I’ve ever believed about my professional field. What are we supposed to believe now?”

I responded:

“It’s not my job to answer that question. My job was merely to put the question in your head.”

"Hubristic humanitarianism" -- another turn of phrase that I will try to remember to credit you for when I steal it. Great article.

I don't know whether he was on record in opposition to eugenics like Chesterton, but C.S. Lewis wrote: "Of all tyrannies, a tyranny exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It may be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience."

> “Progressivism,” from the early 20th century to today, has always been more about means than ends. It is not synonymous with “unbiased,” “caring,” or “broad-minded.”

Very true! Consider this simple thought experiment.

Progressives say "X is a problem, and we need to do Y to counter it."

Person A says "I don't really think X is a problem, but Y doesn't sound so bad; I'm willing to go along with it.

Person B says "Sure, X is a legitimate problem, but Y is really not a good solution and is in fact likely to make the problem worse. We should not do Y, but do Z instead."

Both people disagree with Progressive orthodoxy. Which one are they going to treat as a heretic who must be burned at the stake? We all know the answer already, don't we?