Woodrow the Terrible, Warren the Good

The Upside-down Sensibilities of Presidential Historians. Plus, Tatum and "Tiger Rag."

A few passages of this essay were copied from my earlier “Harding, Wilson and the Perils of Expertise” (2022), published by InsideSources.

Paid subscriptions help keep Bastiat’s Window going. Free subscriptions are deeply appreciated, too. If you enjoy this piece, please click “share” and pass it along.

There are many reasons to disparage what passes for expertise and judgment among presidential historians, but there is none better than their longstanding tendency to rate Woodrow Wilson as a near-great president and Warren Harding as among the worst. By any sensible estimation, Wilson was the ultimate bottom-feeder of American presidents, while Harding swam peaceably, albeit somewhat confusedly, around the middle depths of the pond. But, historians tend to favor leaders with expansive agendas during dramatic times over those with modest goals in calmer times.

In recent years, Wilson’s off-the-charts racism has begun to take him down a notch or two in public estimation, and there have been occasional suggestions that Harding be upgraded a bit. But there’s a long way to go to right the record on these two. Here are some comparisons, informed by my own biases.

Overall

Wilson had some solid accomplishments, but they are buried beneath the inestimable damage he did to the country and to the world. Practically everything wrong with the 20th Century can be traced at least in part to his views, his actions, and his awful personality. Add to this the fact that he was stricken with and incapacitated by a severe stroke in October 1919, hid the news from the American public (including from his own vice president), and allowed his wife to effectively assume presidential responsibilities from his bedside.

Harding was over his head in the presidency and knew it. But his presidency did no great damage and actually accomplished a striking amount of good. The Office of Management and Budget, Government Accountability Office, International Trade Commission, and U.S. Trade Representative trace their origins to his administration. His Supreme Court and Cabinet appointments were mostly outstanding. [Clarification: A reader commented on the destructive economic policies of Treasury Secretary Mellon, Commerce Secretary Hoover, and Chief Justice Taft. I agree with those assessments, but my point here is to describe the intelligence, competence, and honor these officials exhibited.]

After Harding died, he was extremely popular, even among political opponents. Immensely popular while in office, Harding’s posthumous reputation suffered from his naïve trust of unworthy cronies. Interior Secretary Albert Fall was imprisoned for corruption. Harding’s corrupt attorney general, Harry Daugherty, was forced from office by Calvin Coolidge, Harding’s successor. The posthumous revelation that he fathered an illegitimate child during an Oval Office tryst with a much-younger woman really brought the hammer down on his reputation in that rather priggish period.

But consider the following comparisons on race relations, anti-lynching laws, connections with the Ku Klux Klan, taste in film, civil liberties, foreign policy, and self-image.

Race Relations

Wilson was arguably the most virulent racist who ever occupied the White House—more so than any of his slaveholding predecessors. The awful antebellum presidents—Pierce and Buchanan in particular—mostly fiddled while Rome burned. Wilson was the concertmaster who set Rome afire—purposefully destroying a half-century of racial progress. Among his countless iniquities, he purged the Civil Service of African-Americans—thereby erasing decades of modest progress in that arena. He made his toxic bigotry the official policy of the federal government. Even by 1910’s standards, Wilson’s racism was appalling.

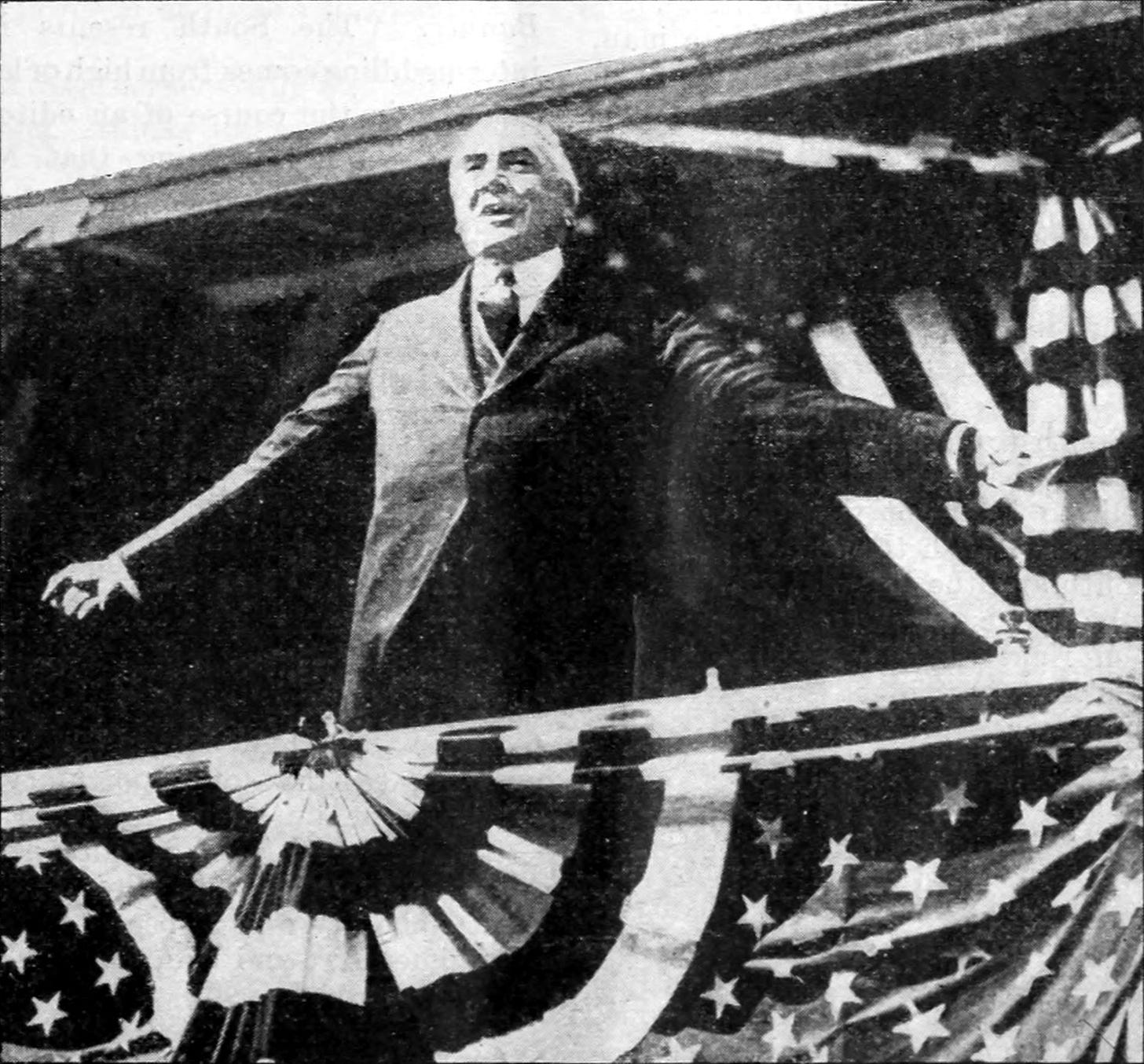

Harding gave the single most courageous speech on race relations ever delivered by an American president—and only a few months into his presidency. He was invited by an Alabama senator to give a speech in Birmingham. To the shock of the crowd (whites in front, blacks in back), he became the first president in history to address race relations head-on. While some of his verbiage is cringeworthy to our ears, in the context of the time his speech was a full-throated call for racial equality—absolutely revolutionary. In a hotbed of Klan activity, Harding declared,

“I can say to you people of the South, both white and black, that the time has passed when you are entitled to assume that the problem of races is peculiarly and particularly your problem, … It is the problem of democracy everywhere, if we mean the things we say about democracy as the ideal political state. … Whether you like it or not, our democracy is a lie unless you stand for that equality.”

It’s worth noting a few reactions to the speech:

Georgia Senator Thomas E. Watson declared that Harding had planted “fatal germs in the minds of the black race.” The junior senator from Alabama, Thomas Heflin, said, “So far as the South is concerned, we hold to the doctrine that God Almighty has fixed the limits and boundaries between the two races and no Republican living can improve upon His work.”

African-American scholar W. E. B. Dubois described Harding’s speech as “like sudden thunder in blue skies.” Marcus Garvey, president of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, telegraphed Harding at the hotel to congratulate him on his speech, "on behalf of four hundred million negroes of the world."

Anti-lynching Laws

Wilson steadfastly opposed anti-lynching laws.

Harding wholeheartedly supported anti-lynching laws—including during the 1920 campaign, when it really mattered. [Additional information: A reader asked for details. Support for anti-lynching laws was mentioned in the 1920 Republican Party platform, and Harding more stridently endorsed the idea in his Birmingham speech.]

Connections with the Ku Klux Klan

Wilson owed his 1912 nomination to the Klan’s open and enthusiastic support, and he repaid them in kind for the entirety of his presidency. [Correction: a reader kindly noted that the Klan was not reconstituted till 1915 and, so, could not have played a role in the 1912 campaign. Edits here correct my error.] Wilson’s most famous book, A History of the American People, was loaded to bear with praise for the Klan. Several of his quotes were displayed in D.W. Griffith’s 1915 The Birth of a Nation, including the one shown above. [added: Wilson’s screening of the film at the White House contributed mightily to the Klan’s ominous rise. Wilson’s racial policies made him a tacit, if not explicit ally of the Klan.]

Harding, according to an almost-certainly fallacious 1980s rumor, joined the Ku Klux Klan and was, perhaps, sworn in at the White House. The claim appears to be a single-source story from a disreputable source, with zero corroboration or credibility. The accusation appeared in the 1985 deathbed confession of a supposedly repentant Klansman, who claimed to have heard the rumor in 1940 from a man who, in turn, claimed to have heard it from someone else in the 1920s. That’s it. That’s the whole chain of evidence. To my knowledge, not another shard of evidence was ever found—and historians did look for it. And other aspects of Harding make the story extremely unlikely—including Harding’s reaction to yet another rumor. In 1920, Wilson’s acolytes, promoting Harding’s and Coolidge’s opponents (James Cox and Franklin Roosevelt), spread a rumor that Harding had an African-American ancestor which, under the “one-drop rule” then gathering steam, would have defined Harding as black. Harding’s response was essentially, “maybe it’s true, and I don’t care.” (His exact words to a journalist were, “How do I know, Jim? One of my ancestors may have jumped the fence.”)

Taste in Film

Harding screened The Covered Wagon at the White House in 1923. It was reportedly his favorite film.

Wilson invited D. W. Griffith to the White House in 1915 for a screening of The hosted a screening of The Birth of a Nation at the White House in 1915–the first film ever shown at the Executive Mansion. [Correction: Contrary to my prior impression, Griffith was apparently not present at the screening.] That film, like Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will twenty years later, The Birth of a Nation was technically pathbreaking but thematically odious. Like Triumph of the Will, The Birth of a Nation became a powerful recruiting tool for hatred, and the Klan owed Wilson an enormous debt of gratitude for boosting it. (Some say he later developed misgivings about the film, but the damage was done.)

Civil Liberties

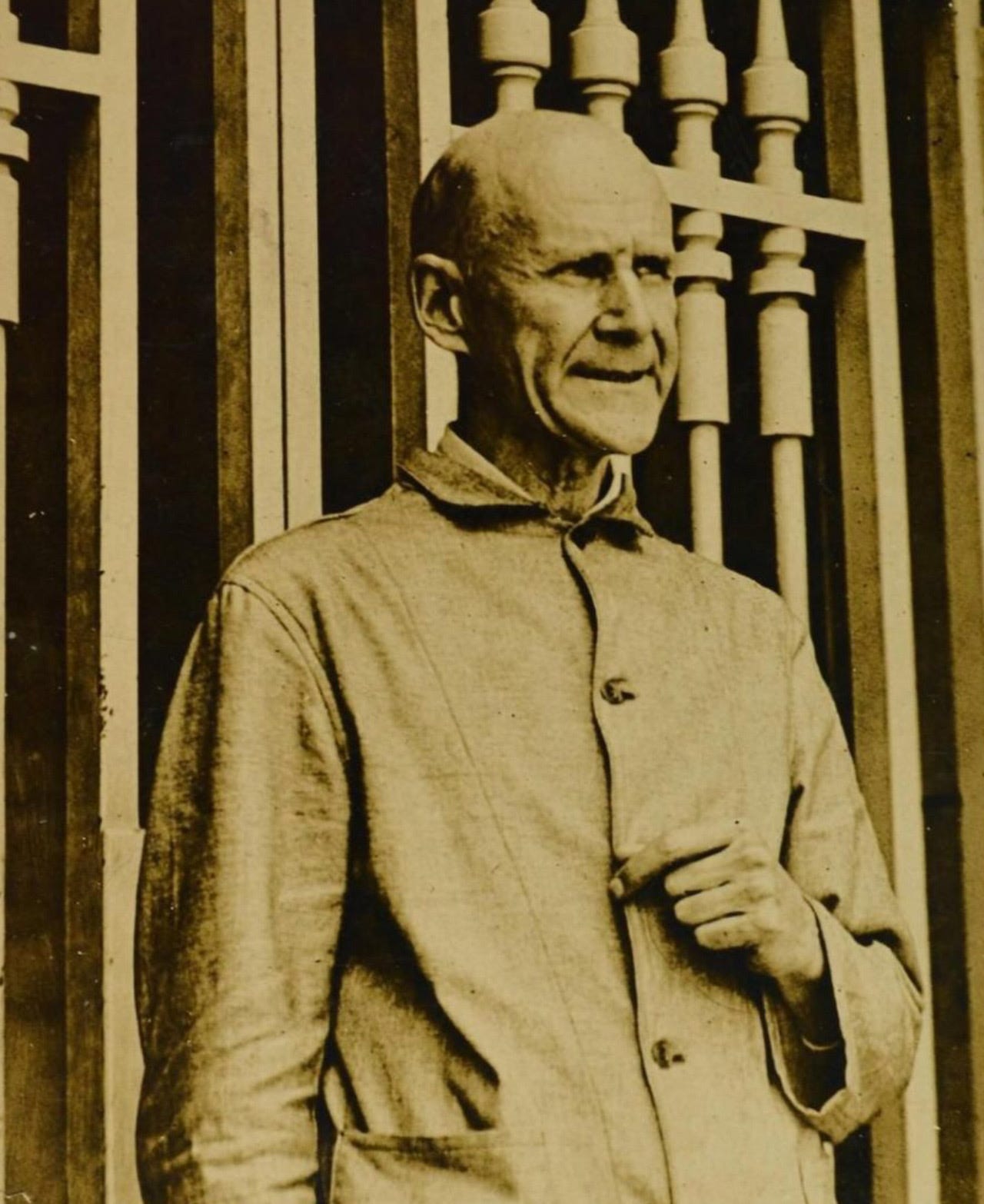

Wilson’s Red Scare policies predated Joseph McCarthy by 40 years, and McCarthy’s abuses pale in comparison with Wilson’s. His Administration’s violations of civil liberties (e.g., the Palmer Raids) were breathtaking. Wilson’s government imprisoned his 1912 Socialist Party opponent, Eugene V. Debs, for peacefully urging resistance to World War I conscription. Wilson wrote,

“This man was a traitor to his country and he will never be pardoned during my administration.”

Harding won the 1920 election, and Debs ran once again, this time from prison. Once Harding had replaced Wilson, he commuted Debs’s sentence and invited him to the White House. When they met, Harding said,

“I’ve heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally.”

Foreign Policy

Wilson promised in 1916 to keep the U.S. out of war and then, the next year, took us into war. The wisdom of that decision is controversial, but defensible. His behavior after the war is not defensible. John Maynard Keynes and others warned Wilson that draconian punishment of Germany at Versailles would lead to disaster, and he ignored all the prescient advice. Fury over his Versailles Treaty was a catalyst for Germany’s monsters — anarchists, communists, proto-Nazis. Wilson dreamed up the League of Nations and then assured its destruction by excluding senators from the treaty discussion and then refusing to even consider the modest compromises that Congressional Republicans wanted.

Harding made significant strides in world disarmament (which, unfortunately, were overcome by the time bombs that Wilson and others had set). Whereas Wilson excluded senators from his treaty discussion, Harding included them from the start and, as a result, won unanimous approval of his arms control treaty. [Note: a reader criticized the results of the disarmament treaty. I agree with him, but my point here was to contrast Harding’s collegiality with Wilson’s imperiousness.]

Conclusion: Self-image

Harding reputedly referred to himself as “a man of limited talents” and said, "I am not fit for the office and should never have been here." He was what Winston Churchill called Clement Attlee: “a modest man with much to be modest about.”

Wilson had a rather different image of self, perhaps described best by Sigmund Freud. According to Freud, an associate remarked to Wilson how proud he was to have contributed to the president’s election victory. Wilson’s icy response was: “Remember that God ordained that I should be the next president of the United States. Neither you nor any other mortal or mortals could have prevented this.”

Lagniappe

Art Tatum’s “Tiger Rag” Visualized

I wanted to offer some musical work from the era of Wilson and Harding and chose this 2-minute, 30-second video that’s stunning to hear and to see. I’ll mention in passing that my childhood was fully immersed in jazz, thanks to my mother, an excellent pianist who was born during Harding’s presidency. (Dad was born during the Wilson years.)

Art Tatum was a nearly blind jazz pianist whose fingers moved with other-worldly speed and precision. “Tiger Rag” is a 1917 song that Tatum performed in a classic 1933 recording. Here, a YouTuber who goes by “itsRemco” uses an AI program to recreate Tatum’s version and to provide striking visuals of what was happening to the piano beneath Tatum’s fingers. The legendary African Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson began playing piano at age 6, and the only time he ever ceased playing was for one month in his teen years. As he told the story:

When I was getting into the jazz thing — or thought I was—as a kid, my father thought I was a little heavy about my capabilities, so he played me Art's recording of "Tiger Rag." First of all, I swore it was two people playing. When I finally admitted to myself that it was one man, I gave up the piano for a month. I figured it was hopeless to practice. My mother and friends of mine persuaded me to get back to it, but I've had the greatest respect for Art from then on.

Peterson’s stature as a jazz pianist would eventually rival or eclipse that of Tatum (and of practically everyone else). But Peterson would always remain shy about performing in front of Tatum. Listen and watch this remarkable rendition.

Another comparison between Wilson and Harding would be Wilson's decision to send U.S. troops to intervene in the Russian Civil War. Compare that to the United States' famine relief effort during Harding's administration.

Wilson was the most outspoken avowed white supremacist President since Lincoln, whose military measure of purporting to free slaves where he didn't have the clout to do so has been used to spin his reputation. Wilson stands out even further from the slavery-era Presidents when one considers that the issue wasn't simply freeing the slaves, but positioning them for self-sufficiency as free people as well. Southerners who voluntarily emancipated slaves before the War took this into account. The Northern states, after they effected compensated emancipation, were apartheid states with laws meant to limit severely the presence of black people. Reconstruction Era officials fomented racial antagonisms, and "Birth of a Nation" fanned the flames. Harding should absolutely be held up as a positive example, as should others who worked for racial reconciliation after Reconstruction.