1,200 Years of British Royalty in 5 Charts

English, Scots, Brits, plus Nordics, Germans, Slavs, Italians, French, and lots of blood

In September, the genuine Elizabeth II passed from the scene, but in November, the fictional Elizabeth II returned for the latest season of The Crown. In the cold winter months of 2018-2019, while planning a trip to Scotland (and, by fortunate accident, London), my wife (Alanna) and I immersed ourselves in Victoria, The Crown, and a long list of other television series and films related to the British, English, and Scottish monarchies. There were so many Henrys, Edwards, James, Georges, etc., confounding our discussions that I decided to untangle the complex histories that ultimately led to Elizabeth II and her progeny.

My central goal was to ascertain how (and whether) Elizabeth II was related to every preceding English and Scottish monarch. Pursuit of that goal led me to condense 1,200 years of English and Scottish royalty into five dense charts, all shown below.

[SIDENOTES: My son Jeremy, mindful of the brief, but memorable Edwardian Era, jested that perhaps our own era will one day be remembered as a new Carolingian Era. (“Carolingian” from the Latin for “Charles.” The “Carolingian Era” usually refers to the rule of Charlemagne and others between 750 and 987.) I replied with a fact I’ve not seen written elsewhere: Everyone knows that at 73, Charles III was older upon becoming king than any other English or British monarch had been on his or her first day on the throne. But less well-known is the fact that Charles III was older upon becoming king than almost any other English or British monarch had been on his or her FINAL day on the throne (i.e., the day they died or abdicated). George II died at 76, George III and Victoria at 81, and Elizabeth II at 96. I believe that’s it. Edgar Æthling died at around 75, but he was booted from the throne at 15—if, indeed, he ever sat on it. Edward VIII died at 77, but Mrs. Simpson’s charms led him astray at 41.]

Producing these five charts was a work of casual genealogy, not a scholarly undertaking—so there are bound to be errors. (I would be thrilled for knowledgeable readers to offer additions or corrections in the comments below.) But I also know that I got a good deal of this right, and discovered some intriguing patterns and connections among European royals.

My research, such as it is, came from a variety sources. This being a casual project, a great deal came from random historical websites. David Starkey’s 17-part BBC series, Monarchy was extremely helpful to this project—as well as wonderfully entertaining. Much of the information on the Scottish throne came from Richard Oram’s delightful little book, The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Now, on to the charts. And, this being 2022, quite a bit came from Wikipedia.

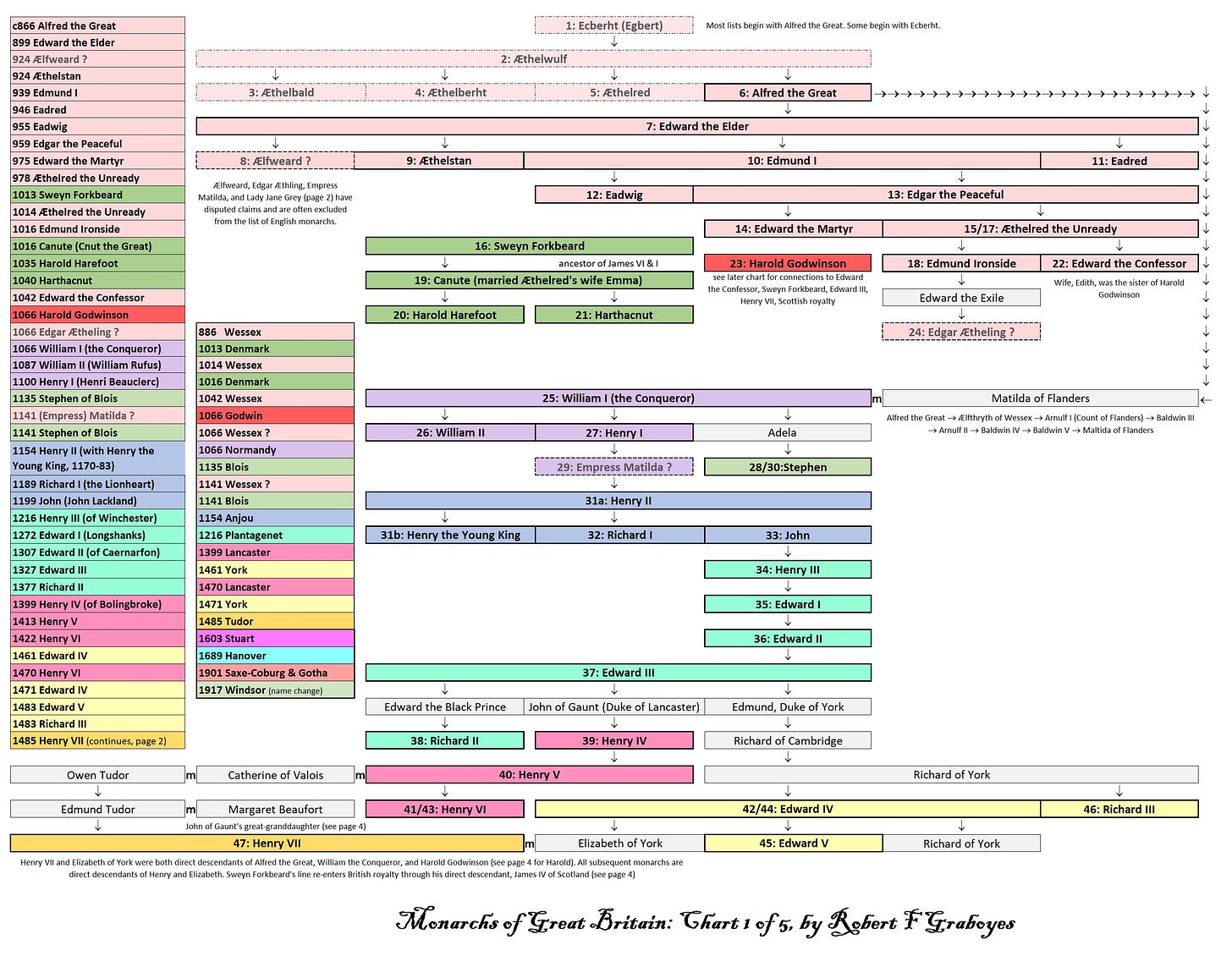

Chart 1: Saxons to Tudors, by Way of the Danes

Today, Alfred the Great (871 for West Saxony and 886 for a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom) is generally considered the first king of England, but during my childhood, that honor was often accorded to Alfred’s grandfather, Ecgberht/Egbert (King of Wessex in 802). Between the ages of 6 and 10 or so, I kept box turtles as pets and, for a time, named them after early English monarchs. The first turtle in that series was Egbert, and for that reason, I shall include those early Saxons in my chart.

Chart 1 shows the entire line of descent from Ecgbehrt to Henry VII (1485). There were three principal challenges to linking the whole group to Elizabeth II. First, in the 1000s, there were four Danish kings of England who, at first glance, are disconnected from the Anglo-Saxons who preceded them and from the rulers who came after. Second, the unfortunate Harold Godwinson (1066) floats on the chart as a solitary dynastic island, unconnected to the Anglo-Saxons and Danes who preceded him and the Normans who followed. Third, the connections between William the Conqueror (1066 and all that) to his predecessors are not obvious at first glance. The Danes’ and Harold’s connections to Elizabeth II and Charles III are revealed on Chart 4. Chart 1, however, ties the descendants of William the Conqueror to Alfred the Great and the other Anglo-Saxons by way of William’s wife, Matilda of Flanders. Matilda was the great-great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Alfred, so all subsequent English and British monarchs are direct descendants of Alfred by way of Matilda. Perhaps William has some ancestral connections to the Anglo-Saxons, but I couldn’t find any.

A few other things bear mentioning before moving on to Chart 2. These instructions for reading Chart 1 will apply to later charts, as well.

Monarchs in lighter type and dashed boxes are those whose status as English monarchs is disputed. That includes Egbert and the other pre-Alfred kings (and one of Alfred’s sons). It also includes the aforementioned Edgar Æthling (also 1066) and the Empress Matilda (granddaughter of William and Matilda of Flanders), whom some argue was England’s first queen regnant (1141).

Downward arrows show parent-to-child relationships.

Boxes in the same row that touch indicate siblings or half-siblings.

Boxes in the same row that are separated by a space are cousins.

Numbers indicate the order of rulers. So, for instance Æthelred the Unready is both #15 and #17, as his reign was interrupted by that of #16, Sweyn Forkbeard of the House of Denmark.

For Charts 1-3, colors differentiate dynasties. On Chart 4, colors refer to countries. On Chart 5, colors refer to mode of dying.

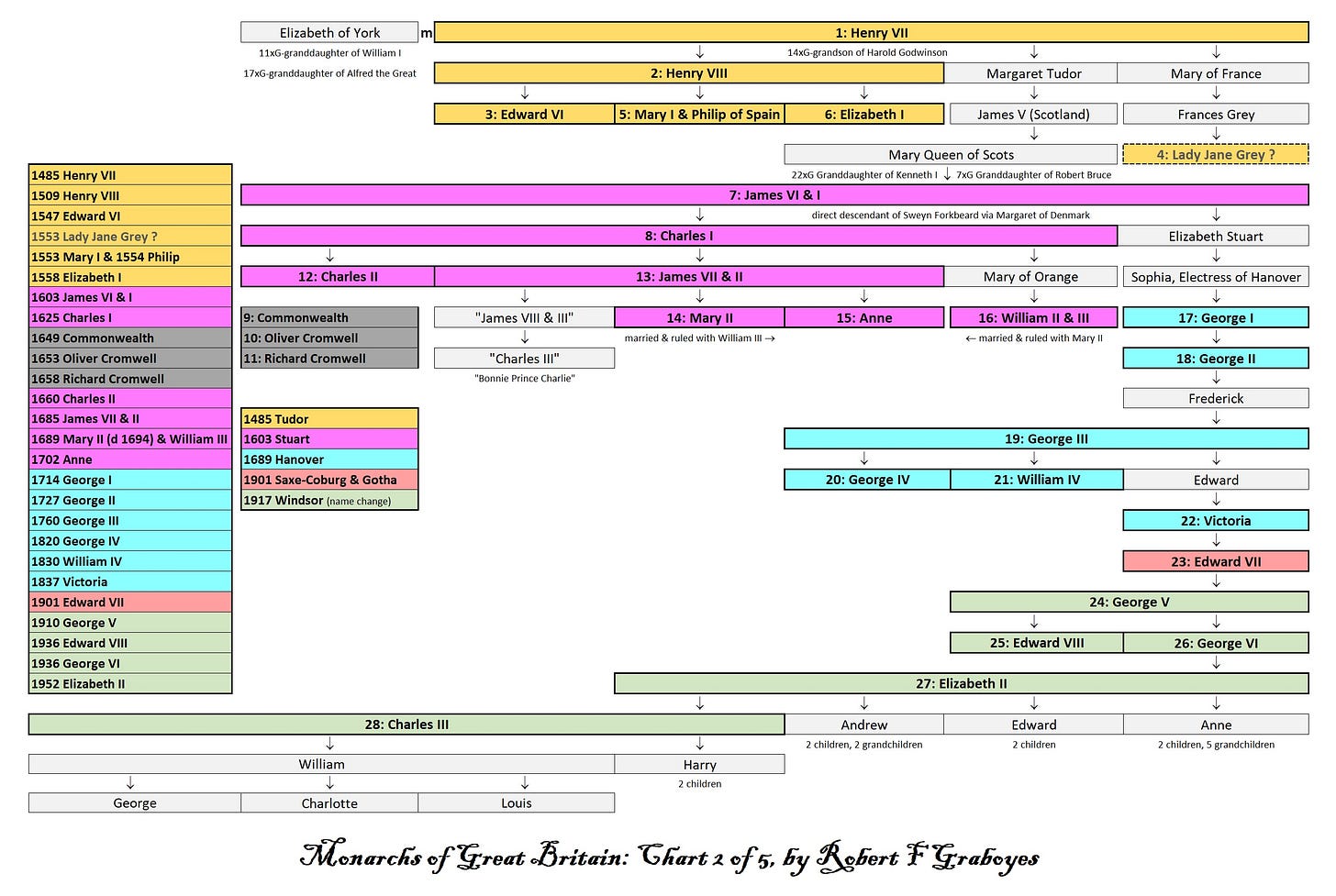

Chart 2: Tudors and Stuarts and More, Oh My

Chart 2 is a continuation of Chart 1, showing the descendants of Henry VII and his great-great-great-great granddaughter, Sophia, Electress of Hanover. Under the Act of Settlement of 1701, all British monarchs must descend directly from Sophia, who barely missed the opportunity to rule the United Kingdom. The elderly but robust Sophia, who was heir presumptive to the throne, died less than two months before the younger, but sickly Queen Anne.

Note the small type at the top. Henry VII was descended from Harold (as shown on Chart 4), and his wife, Elizabeth of York, was descended from both Alfred and William (shown on Chart 2). We also begin to see near the top how the current British royal family is descended from the Scottish rulers back to Kenneth MacAlpin (841). After the Tudors die out, the English throne shifts to a parallel line through Henry’s daughter, Margaret Tudor, who (as shown on Chart 3) marries Scotland’s King James IV. Also, on this chart, the monarchy is interrupted by the English Civil War and the brief rise of the Cromwells. This chart also shows the shift from the Catholic James VII and II to his Protestant daughter Mary II after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This succession required England and Scotland to skip over her older brother James and his son “Bonnie Prince Charlie.” (Fans of the TV series Outlander will know all about Charlie’s failed Jacobite uprising, but it’s helpful to see that bit of history on a chart.) Finally, with the end of the Stuart line, we see the shift to the Hanoverians and their descendants up to the present.

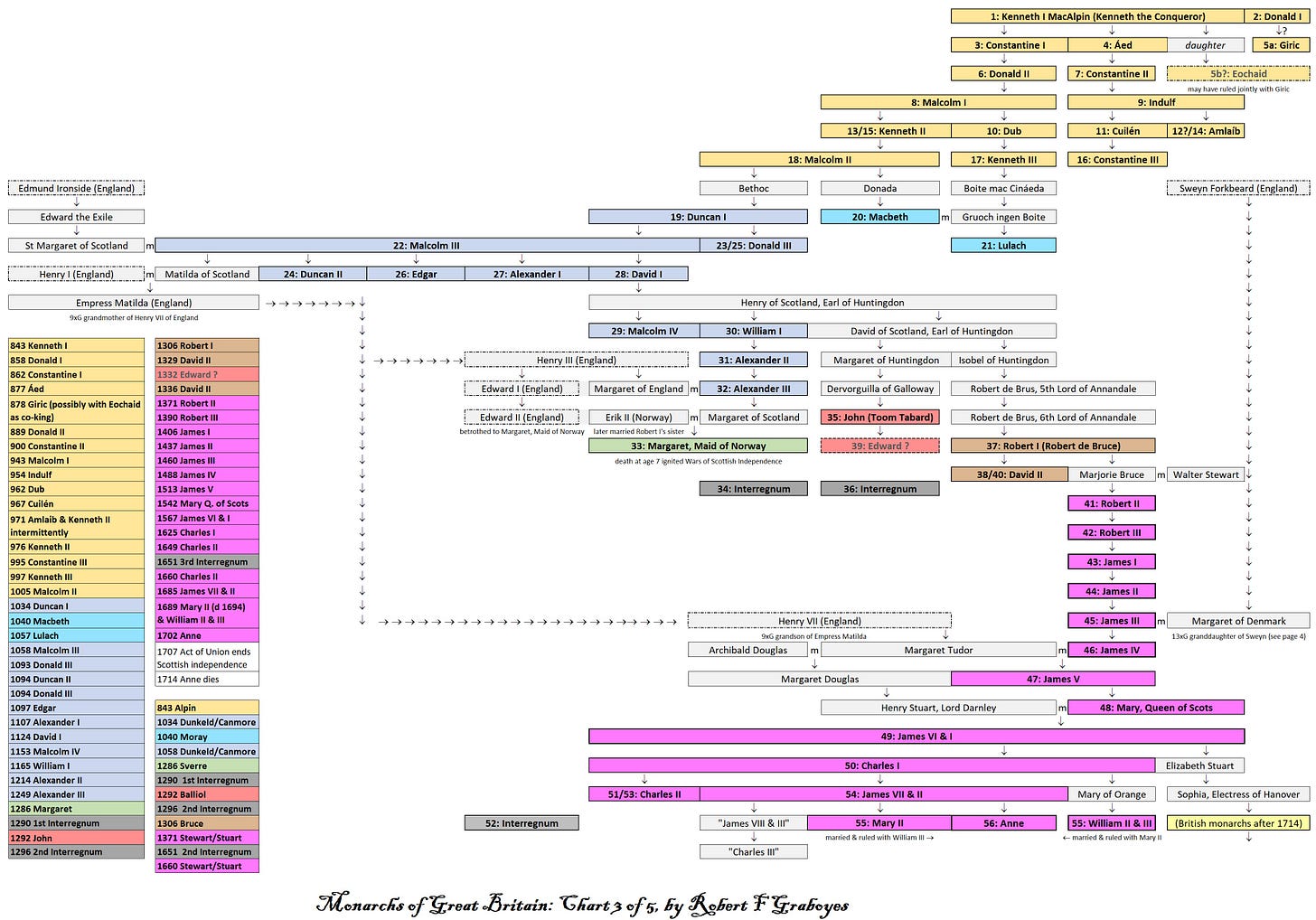

Chart 3: All Things Scottish

Chart 3 covers the Scottish monarchy from the time of Kenneth MacAlpin to Anne (1702). (The Scottish throne ceased to exist with Scotland’s unification with England under the Acts of Union in 1707.) The Scottish monarchy was far more unstable than the fairly straightforward lines of the English monarchy, but some geometric prestidigitation made it possible to tie all the Scottish rulers from Kenneth MacAlpin to Anne into one big not-so-happy family. Under the Alpin Dynasty, follow the numbers. The Scottish throne bounces back and forth like a tennis ball between two lines. (NOTE: That’s appropriate, since their descendant, James I of Scotland—not James I of England—was murdered because he had blocked up his escape route to prevent his tennis balls from going into a sewer.). This chart shows later examples of the throne bouncing between rival family lines. Ultimately, the line settles down after Robert I (Robert the Bruce) and then heads straight down to London.

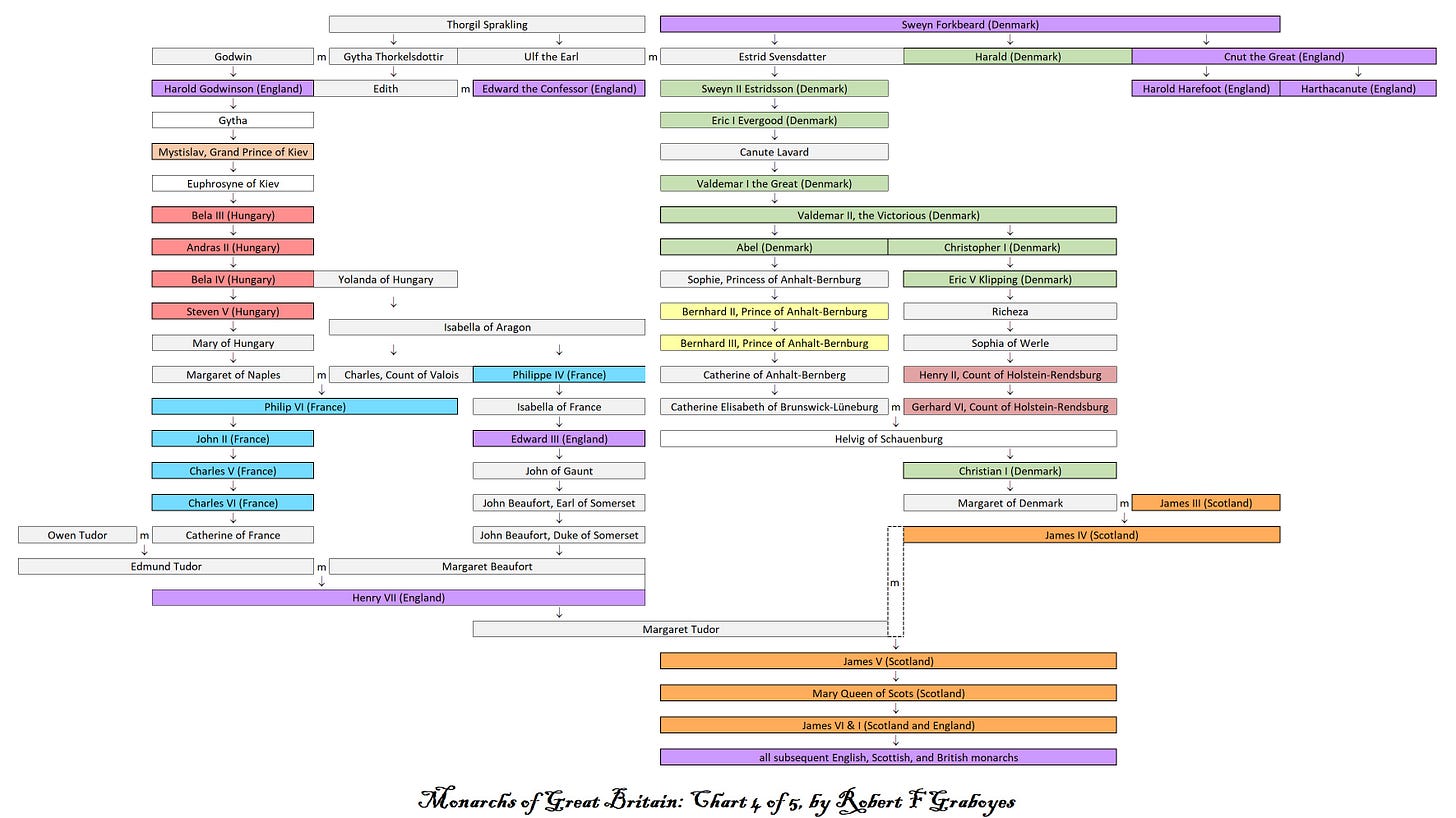

Chart 4: Danish DNA’s European Tour

My toughest task was to map out how Elizabeth II was related to the Danish kings and to poor Harold. Here, we find some unexpected connections. (Unexpected for me, anyway.) Harold Godwinson’s descendants pass through nobility and royalty in Kiev, Hungary, Naples, France, and then back to England, where, after 15 or 16 generations, his DNA makes its way to Edward III—ancestor of all subsequent English and British rulers (and perhaps a direct ancestor of 80% of all pre-immigration Brits). Harold’s mother, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, had a brother, Ulf the Earl, who married Estrid Svensdatter, who was the daughter of the Sweyn Forkbeard—the first Danish king of England. I didn’t need to include all the detail in the previous sentence, but I really wanted the opportunity to type all those Game of Thrones-type names.

Chart 4 also shows how the modern British royals are descended from those Danes. The Danish line led into rulers of some smaller German kingdoms and then to James III of Scotland—from whom all subsequent English, Scottish, and British monarchs are descended.

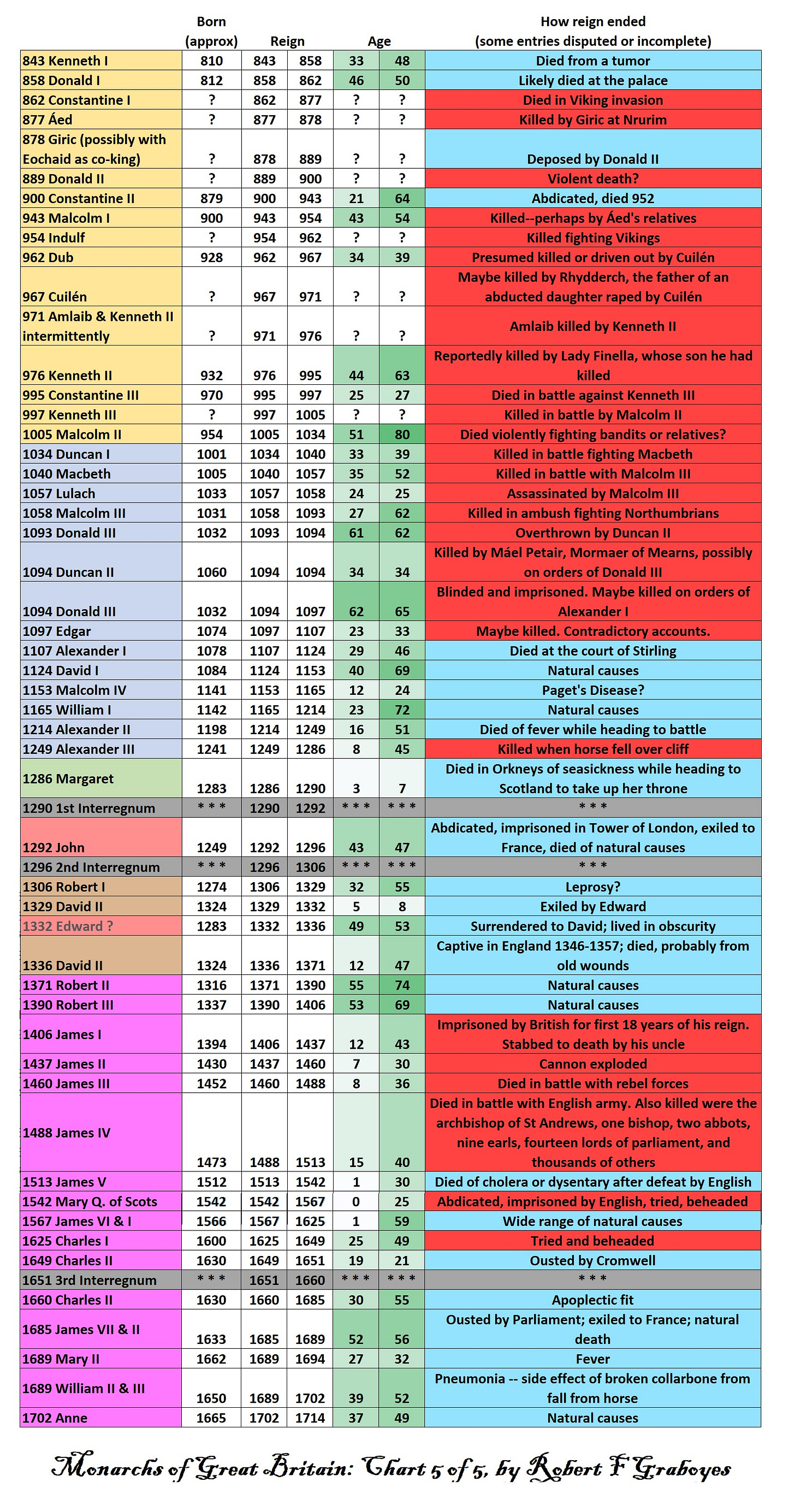

Chart 5: A Bloody Good Time Was Had by All

Chart 5 was a rather gruesome bonus diagram. After reviewing all this history, Alanna asked, “Exactly how many of these Scottish monarchs died violent deaths?” The quite-striking answer is answered in this chart’s color-coding. Blue indicates a natural death. Red indicates a violent death—the most recent of which was the English/Scottish king Charles I, beheaded at the time of the English Civil War. Suffice it to say that very few Scottish monarchs’ obituaries read, “Died peacefully at home, surrounded by loving family.”

Well, crap. So much for being able to watch a costume drama without being related to any of the characters (as I just did—or thought I did—with "Anne of the Thousand Days" off TCM). Malcolm, Duncan, and Kenneth MacAlpin? Directs, via a Spence colonial ancestor. Alfred the Great? Ditto. Mathilda of Flanders and William the Conqueror? Yep, via the first two Henrys and John on the wrong side of the blanket. And, actually, six of Henry I's two dozen mistresses.

Granted, with those exceptions, the relationships are pretty darned remote, so I reckon I can continue to ignore them and concentrate on the direct ancestors. With a few exceptions, like Great Aunt Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, who kicked Danish behind. And Cousin Elizabeth II, because I know the two places where we share directs and I'm kind of a fan of hers.

Great job, Mr. G. ... I just didn't need to know that the whole lot of them are cousins of some sort.

Mary and Anne were actually older than their brother James as they were born to James II and his first wife, Ann Hyde. Their brother was born to James II And his second wife, a Catholic. Because males took precedence, James should have been James III, but as already mentioned, William of Orange, aided by John Churchill and others, made sure he and his father never got back on the throne.