Bastiat’s Window is a journal of economics, science, and culture—with a special focus on healthcare and technology. Some recent articles have focused on censorship, eugenics, healthcare prices, freedom, presidential history, the gig economy, effective altruism, abuse of the word “equity,” politicization of medicine, artificial intelligence, and the travels of an economist in Sub-Saharan Africa and in Scotland. More eclectic pieces have covered the anthems of America’s eight (nine?) uniformed services, the peculiarly American story of paw-paw trees, and the case for awarding the Nobel Literature Prize to Vince Gilligan.

If you enjoy Bastiat’s Window, please consider becoming a paid or free subscriber, and by all means, share the site and its articles with friends and colleagues.

FOREWORD BY BOB GRABOYES

In 1974, a casual get-together at the Two Continents bar near the White House made economic and popular history when economist Arthur Laffer sketched out a counterintuitive taxation concept on a cocktail napkin—the idea that lower tax rates might earn the government higher tax revenues (and boost the economy, to boot). Seeing the economist draw his famous curve on a cocktail napkin is not quite the same as witnessing the receiving of the tablets on Mount Sinai or the signing of the Magna Carta—but it’s the closest thing that modern economics has to offer. The Laffer Curve vaulted into the media, policy debates, public discourse, and, eventually, an exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution.

Details of the get-together at Two Continents have now circulated for 49 years, and the details change from telling to telling—including who was present. The napkin displayed at the Smithsonian is of dubious provenance and even Laffer’s close associates are unsure of details. While a couple of eyewitnesses mentioned the meeting in their writings, I don’t believe any ever wrote a detailed account of the event for public consumption—until now. Art Laffer himself wrote that he does not actually remember the details of the event. The Laffer Curve and The Napkin gained currency in the writings of another attendee, financial journalist and political advisor Jude Wanniski, who arranged the meeting. By chance, my friend and colleague, Grace-Marie Turner (née Grace-Marie Arnett) was one of that small group who witnessed the sketch on The Napkin. I asked her if she would share her recollections of that day and clear the air on some of these questions. She kindly agreed to do so, and the result is the essay below—the very first guest post on Bastiat’s Window.

The name “Laffer Curve” is an example of Stigler’s Law of Eponymy, enunciated by statistician Stephen Stigler, which states that no scientific discovery is named for its actual discoverer. In the previously mentioned link, Laffer noted that the concept behind the curve had been articulated in different forms by Ibn Khaldun in the 14th century and John Maynard Keynes in the 20th century. He credited future Nobel Laureate Robert Mundell (whom I wrote about a few weeks back) as the source of his ideas. Others have noted that antecedents can be found in the writings of Adam Smith in the 18th century and Andrew Mellon in the 20th. But Laffer’s impromptu sketch made the opaque intuitive, and so it is his name that is forever attached to the idea. (By the way—Stephen Stigler said that Stigler’s Law was actually discovered by sociologist Robert Merton.)

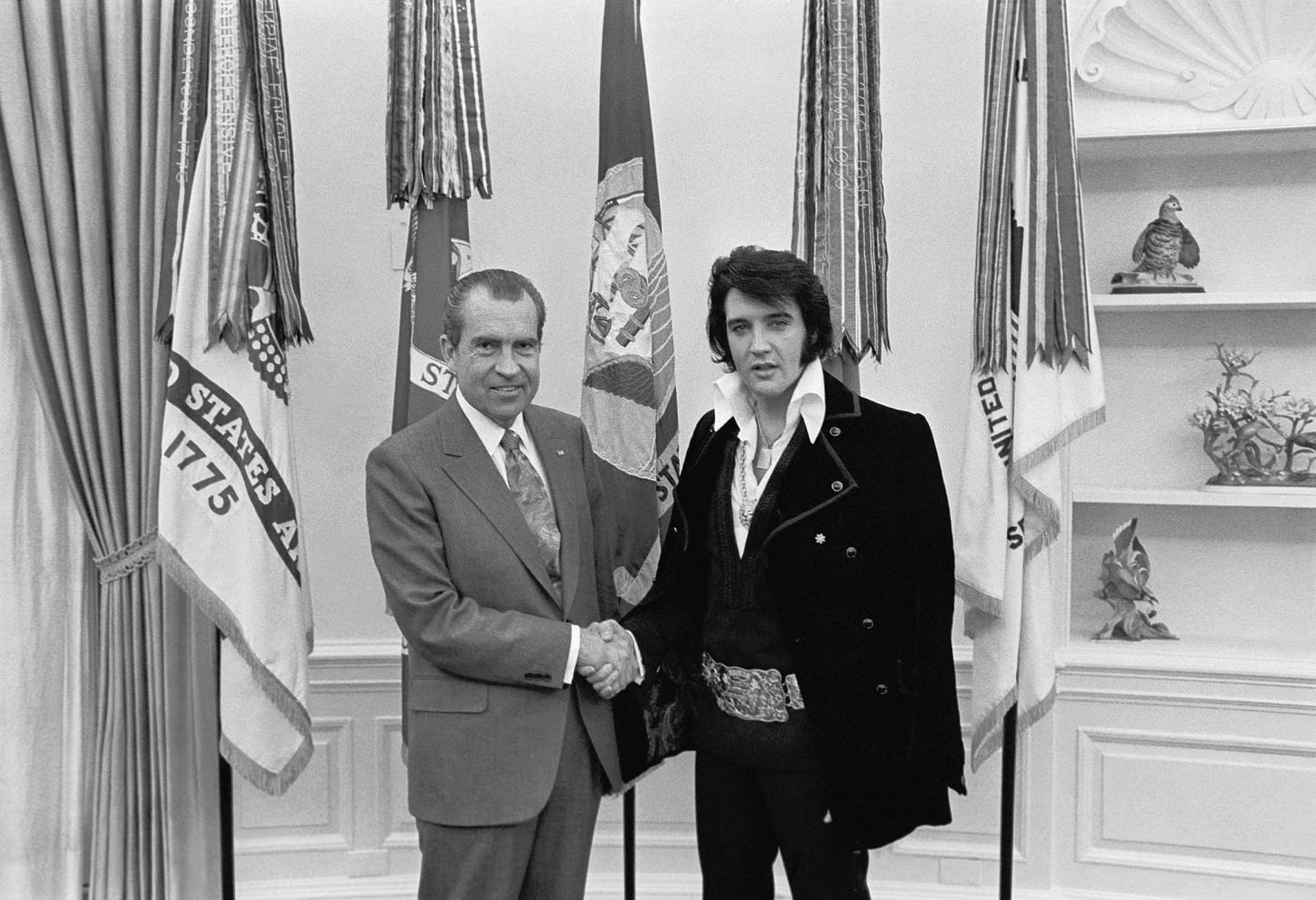

One final note: Grace-Marie’s article mentions the famous meeting between Richard Nixon and Elvis Presley (delightfully portrayed in the 2016 film, Elvis & Nixon). It turns out that Grace-Marie interviewed Elvis when she was a young reporter in Albuquerque, New Mexico. No promises, but perhaps we can persuade her to share that story in the future.

Birth of the Laffer Curve:

Eyewitness to the Cocktail Napkin that Launched a Presidency

By Grace-Marie Turner

History was being made that late afternoon in the fall of 1974, but it seemed at the time to be just another meeting of Washington power brokers (and one young journalist) over cocktails at a hotel bar.

The iconic Hotel Washington at 15th and F streets is directly across the street from the Treasury Department and just a block from the White House. It was then more famous for being the hotel where Elvis stayed when he made his surprise trip to Washington to commandeer a meeting with President Nixon, wanting to help with his anti-drug campaign.

The bar next to the Hotel Washington’s Two Continents restaurant was the setting for the 1974 meeting with Dick Cheney, then serving as deputy chief of staff to President Gerald Ford. It was arranged by Wall Street Journal editorial writer Jude Wanniski to introduce the exciting ideas of a brilliant young economist, Art Laffer. (Some accounts say that then-chief of staff Donald Rumsfeld also attended the meeting, but it is unlikely that the top two staffers at the White House both would venture out to meet an economist and a journalist for drinks. Rumsfeld may have joined later, but I don’t recall his being there when Laffer drew his famous sketch.)

Wanniski was obsessed with Laffer’s ideas about the impact of tax rates on economic growth. With the nation in a deep slump—high gas prices and inflation, soaring unemployment, and sluggish economic growth—Wanniski was hoping Cheney would embrace Laffer’s tax-cut idea as a centerpiece of President Ford’s upcoming 1976 election campaign.

(We can’t call it a re-election campaign because Ford, who had been the top Republican in the House of Representatives, was confirmed as Nixon’s vice president in November 1973 after Vice President Spiro Agnew was forced to resign amidst his own scandal. When Nixon resigned in August of 1974, Ford became the first, and so far the only, person to become president without winning a general election for president or vice president.)

Ford had been well-liked and popular in Congress, but he faced a huge backlash after pardoning Nixon. Ford was willing to take the heat for his decision, rather than prolong the Watergate scandal through an impeachment trial that would last months and possibly years. But his poll numbers had plummeted, and he needed to turn the page.

Former California Gov. Ronald Reagan was planning to challenge Ford for the 1976 Republican presidential nomination, and Wanniski felt Ford needed fresh and exciting ideas to revive his new presidency.

Wanniski had been proselyting in his Wall Street Journal editorials about the need to cut sky-high tax rates since meeting Laffer. It was a major win when he wrangled a meeting to give Laffer a chance to explain his proposal to Cheney and possibly win over the White House. (And there was a connection: Laffer and Cheney both were class of ’63 as undergraduates at Yale—before Cheney departed to finish his studies in Wyoming.)

The dimly lit hotel bar had a row of diner-type tables lined up in front of Naugahyde-upholstered benches along the back wall, with standard hotel chairs on the outside. Nothing fancy, especially compared to the swanky hotel it is today. A glass of wine and two beers were the libations of the hour.

Laffer, then a professor of economics at the University of Chicago who had previously served as chief economist in Nixon’s Office of Management and Budget, wanted Cheney to understand that high taxes were stifling productivity and investment. Cutting taxes would fuel economic growth, and robust growth would, in turn, yield more revenue to fund the federal government.

Cheney was having a hard time grasping the concept.

Wanniski described the moment in his book, The Way the World Works. (Basic Books, 1978):

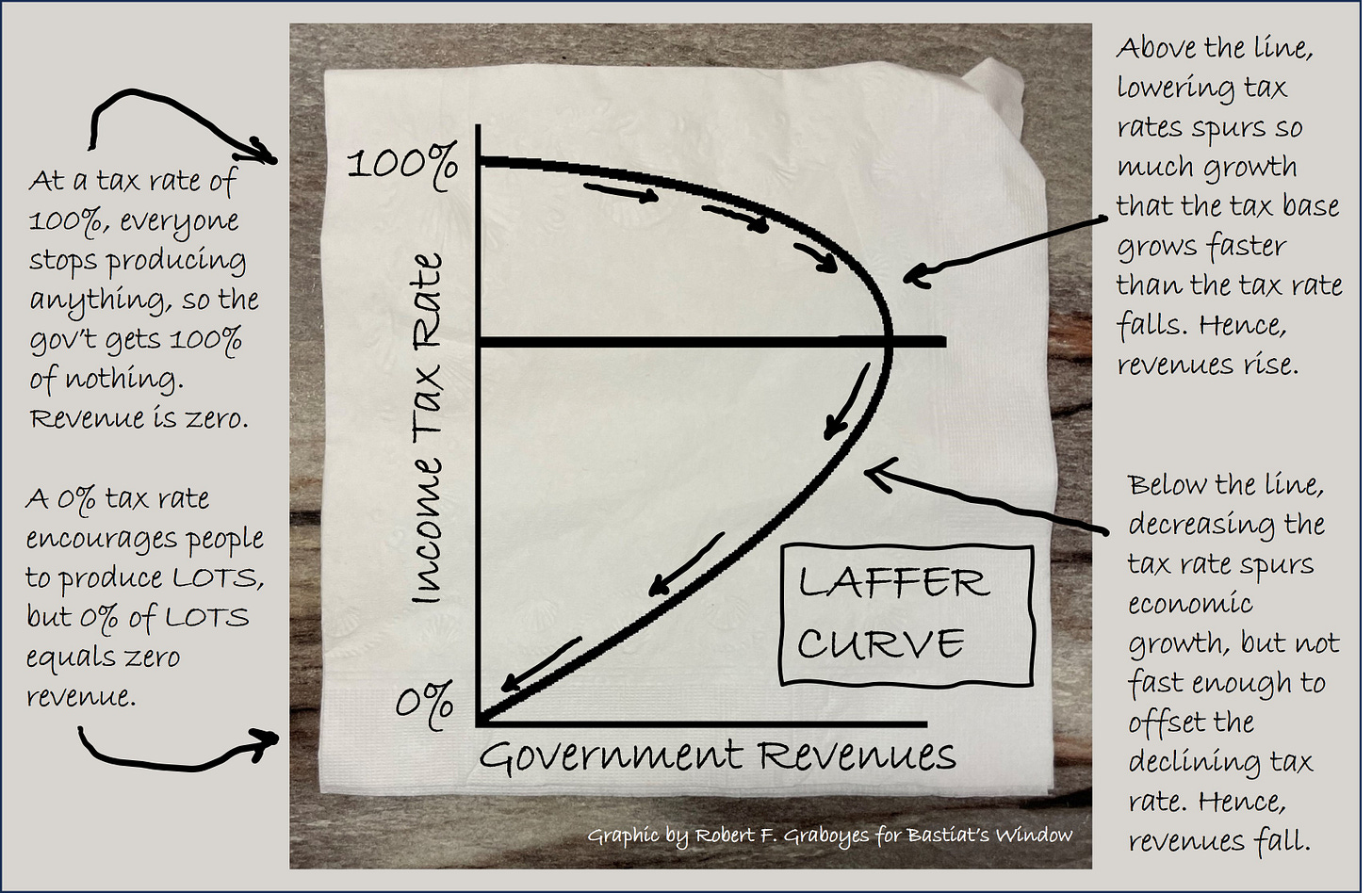

“‘There are always two tax rates that yield the same revenue,’ observes Arthur Laffer …[who] drew the curve shown above to illustrate his point.

When the tax rate is 100 percent, all production ceases in the money economy. People will not work in the money economy if all the fruits of their labor are confiscated by the government. An individual will not work for $1,000 a day if, after taxes, his paycheck comes to zero. Because production ceases, there is nothing for the government’s 100 percent rate to confiscate, and revenues to the state are also zero.

On the other hand, if the tax rate is zero, people can keep 100 percent of what they produce in the money economy. There is no government wedge, and thus no governmental barrier to production, so production is maximized … but because the tax rate is zero, government revenues also are zero.”

Political leaders’ job is to find that optimal balance where workers and investors are incentivized to work and produce but where there is sufficient revenue for the government to operate and provide its essential services.

President John F. Kennedy in the previous decade had announced “an across-the-board reduction in personal and corporate income tax rates,” tax cuts that were enacted by Congress after his tragic assassination. Wanniski and Laffer hoped President Ford would campaign on a promise to lower federal tax rates to boost productivity and economic growth and with it, increase federal revenue collections.

One of Wanniski’s most famous Wall Street Journal editorials was entitled “Tax the Rich!” The rich will pay more in taxes if they get to keep more of what they earn, he argued, with ample subsequent evidence to prove him right.

Ford didn’t buy it—choosing instead to run on slogans like “Whip Inflation Now” that turned into a catchy “WIN” campaign button.

In 1975, the Ford campaign was ramping up, with the first-in-the-nation New Hampshire primary just months away. President Ford traveled to New Hampshire earlier that fall to seek votes for Louis Wyman, the Republican candidate in a special Senate election. The election had been ordered by the U.S. Senate because the race between Wyman and Democrat John Durkin the year before had been too close to call. Wyman went on to lose the special, but Ford had been well received as huge crowds turned out to cheer his motorcade as he crossed the state, holding multiple rallies on a day of bright sunshine as autumn leaves were just starting to turn.

While Ford prevailed against Reagan for the Republican presidential nomination the next year, he went on to lose the general election. Wanniski, meanwhile, moved on to recruit other politicians, contacting a then-obscure former football player who was representing Buffalo, NY, in Congress—Jack Kemp. The Laffer Curve idea also caught fire with Kemp, a self-taught student of economics, who became one of its leading evangelists.

After Reagan’s hard-fought primary loss to Ford in 1976, the former California governor was planning to run again in 1980 and was convinced he needed a bold new idea to pull the nation out of the Carter-era malaise. He took a briefing with Laffer, Wanniski, and Kemp in California to learn about their idea.

Reagan was sold. The promise of a 30% across-the-board tax cut became the centerpiece of his domestic campaign plan. He prevailed in 1980 to win the Republican nomination and the presidency—and ushered in two decades of prosperity with the passage of the Economic Recovery Tax Act, a.k.a. the Kemp-Roth Tax Cuts.

So why was I there when Art drew his famous Laffer Curve? Because Wanniski previously had tried to convince my former boss, New Mexico Senator Pete Domenici, to get on board with supply-side, incentive economics. Domenici didn’t buy it, but, as his press secretary, I sat in on the meeting and was convinced this was an exciting idea that made sense and would resonate with voters.

I had moved on from Domenici’s office to work as the Washington correspondent for The Fort Worth Star-Telegram. I was studying these fresh new economic ideas. Wanniski, always trying to recruit new disciples, invited me to tag along as well.

Who knew that little cocktail napkin that Laffer scribbled on that night would become so famous?

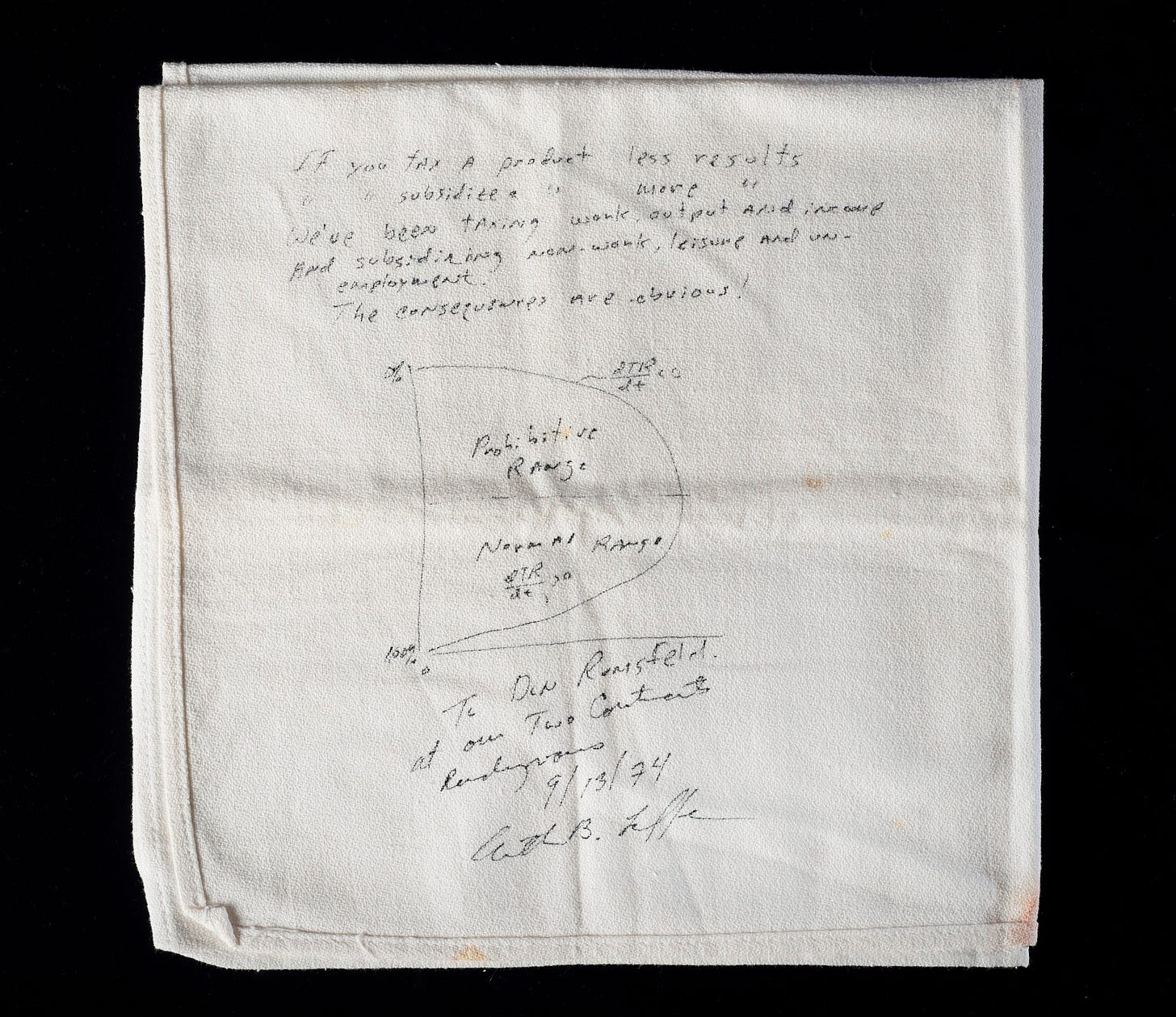

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History purports to have a Laffer Curve napkin (shown above), but it is cloth and looks like a folded dinner napkin. The casual bar at the Hotel Washington was much more likely to have had paper cocktail napkins. And who would take a pen and ink to a cloth napkin anyway—not to mention signing and dating something that none knew at the time would be regarded as historic? (Art himself said years later that he had better manners than to think he could ruin a nice napkin with a pen.)

But apparently he did ruin some cloth napkin at some point, creating a wonky souvenir “to Don Rumsfeld.” The Laffer Curve napkin the Smithsonian displays is surely one that Art created—his staff says it is his handwriting—but it must have been drawn later on. I have no memory of Donald Rumsfeld being at the cocktail table when the first sketch was made. But Art surely got together with him later to recreate the Curve for him. And Wanniski must have been there to take it home since the Smithsonian’s version was found in his collections by his widow, Patricia.

So while the original napkin may have been lost, the ideas prevailed to produce tens of trillions of dollars in economic growth and lead to prosperity that has freed billions of people across the planet from grinding poverty. In 1999, Art Laffer was named by Time magazine as one of the greatest minds of the 20th century and, in 2019, was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

What are the lessons in all of this? First, ideas can be powerful. Second, persistence is essential. Third, save that sketch on a cocktail napkin. It could prove to be an historic and transformational document.

Grace-Marie Turner founded the Galen Institute in 1996, a non-profit think tank that works to promote an informed debate over health reform ideas centered around doctors and patients. She began her career as a journalist where she wrote extensively about politics and tax policy. Before founding the Galen Institute, which she has run since the beginning, she served as executive director of the National Commission on Economic Growth and Tax Reform, a.k.a. the Kemp Commission. She recently was included, for the third year in a row, in the Washingtonian’s list of the 500 Most Influential people shaping policy.

Lagniappe

Meredith Willson, Music Man to Inflation-Whipper

by Robert Graboyes

Meredith Willson is best known for his 1957 hit Broadway musical, The Music Man—a truly iconic piece of Americana—and enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a composer, performer, and playwright. He is perhaps least known for his 1974 composition, “WIN!”—his marching song for President Gerald Ford’s “Whip Inflation Now” (WIN) effort. It is fortunate for Mr. Willson that hardly anyone remembers “WIN!” and that it is nearly impossible to find a recording.

President Ford’s WIN effort was notoriously unsuccessful and an object of withering ridicule. The idea was to talk down the decade’s raging inflation by persuading ordinary Americans to save more and spend less. But 1970s inflation was ultimately tamed, not by a PR campaign, but rather by a disciplined, credible Federal Reserve, led by Chairman Paul Volcker.

I heard “WIN!” precisely once, on TV, banged out on a piano by Willson himself. I can barely remember the melody, but the lyrics still trigger a sort of musical PTSD in me:

“Win! Win! Win!

We'll win together,

Win together, That's, the true American way, today.

Who needs inflation?

Not this nation.

Who's going to pass it by?

You are, and so am I

Win together.

Lose? Never!

If you can win, so can I.”

Lest anyone think I am anti-Willson, one of my young life’s greatest experiences was conducting the pit orchestra for my high school’s 1972 performance of The Music Man—just two years before “WIN!” Better to remember the maestro for a piece like “Till There Was You,” performed here by The Beatles:

Fun read, especially with the unexpected reference to Meredith Willson!

One can almost smell the stale beer on the restaurant's floor. The 4th lesson is "a picture is worth a thousand words." The drawing with Art explaining it would make sense to almost anyone. Without the drawing, it would seem baffling to most people. Of course, it also oversimplifies a very complex issue and makes assumptions that have been endlessly debated....

On the more important matter of the artifact: clear evidence that the Smithsonian item isn't the original is all the detail, including math formulas. No conversation over drinks in DC involves differential equations!