Chickens and Neutrons and Long-leggedy Horsies and Things that Go Pump In the Night

Three mini-essays on innovation, plus kids with horse sense

Paid subscriptions help pay the bills at Bastiat’s Window. Free subscriptions are deeply appreciated. Sharing Bastiat’s Window essays helps the site to thrive.

Today’s four-part offerings: [1] Inventing the Chicken: Why a future Nobel laureate thought the chicken was the most important invention of the 20th century. [2] Innovation as Fission: How innovators and innovations resemble a nuclear reactor. [3] Fear of Pumping in Oregon: How gas stations terrify Oregonians. Plus, [4] Kids with Horse Sense: How responsibility for animals makes better kids.

Inventing the Chicken

No, Thomas Edison didn’t invent the chicken, despite my fake, AI-generated photographs above. But around the time of the Apollo moon landings, a future Nobel laureate allegedly declared that the most important invention of the 20th century was the chicken. This cryptic statement offers profound wisdom about possible paths of healthcare innovation in the 21st century. The chicken quote was attributed to Robert Mundell, 1999 Nobel economist, by Dick Zecher, who was my boss at Chase Manhattan Bank and, before that, Mundell’s colleague at the University of Chicago.

How is the chicken — first domesticated more than 5,000 years ago — a 20th-century invention at all? And how was the chicken more important than the airplane, computer, atomic bomb, television, interplanetary rocket—or the countless works of Edison and his crew?

Dick told me that the comment, delivered during an Economics Department seminar, attracted the blank stares that often met Mundell’s odd, enigmatic, and always-profound observations. After a prolonged silence, the befuddled seminar speaker asked what Mundell meant.

His insight was that in the 20th century, modern production methods so drastically reduced the price of chicken that the bird became, for all practical purposes, an entirely new good. According to W. Michael Cox and Richard Alm (“Myths Of Rich And Poor: Why We're Better Off Than We Think”), a typical American in 1900 worked 160 minutes to earn enough money for a 3-pound chicken. An equivalent worker in 2000 needed only 14 minutes of wages to buy that chicken. Pre-1950s, consumers generally had to eviscerate a commercially bought bird or have a butcher do it. (My mother used to shudder when she recalled the itinerant butcher who would slaughter chickens for my grandmother in their kitchen sink.) Herbert Hoover’s promise of “a chicken in every pot” rings dull to our ears, but in 1928, the phrase sounded like “a flying car in every garage” sounds to ours.

Revolutionary production, distribution and storage methods changed chicken from a Sunday luxury item to the everyman’s protein. Our concept of chicken bears little resemblance to our great-grandparents’ image. Massive reductions in food prices explain why rates of malnutrition and starvation have plummeted worldwide since the mid-20th century.

POSTSCRIPT: This piece was adapted from my “The Invention of the Chicken and Innovation in Healthcare,” published by InsideSources in 2017. As a student at Columbia University, I often witnessed Mundell’s surreal genius, which I described in an earlier post at Bastiat’s Window: “The Pigeons of Rothschild: Telegraph, Internet, and Paris Hilton.” After Dick Zecher died in 2021, his business partner, Damian Handzy, wrote a touching tribute to him that is filled with worthy life lessons—most notably the importance of not burning bridges. Handzy recalled that Dick often joked that he, Deirdre McCloskey, and Art Laffer were the only three University of Chicago economics professors who failed to win the Nobel Prize.

Innovation as Fission

Innovation has long reminded me of a controlled nuclear chain reaction—with innovators as free neutrons and innovations as fissionable nuclei. Laws and regulations are the equivalent of control rods.

In a reactor core, control rods reduce the number of neutrons that strike and split nuclei. With too few rods, too many neutrons split too many nuclei, and the dreaded meltdown occurs. With too many rods, the number of neutrons striking nuclei becomes too small to sustain a chain reaction.

Like nuclear fission, technological innovation can only thrive in an atmosphere that is both orderly, yet conducive to chance encounters. That atmosphere might be embodied in formal laws and regulations defining and enforcing intellectual property rights. Contract laws must enable innovators to buy, sell, and manage risks and the fruits of their labor. Tort laws must offer redress to individuals harmed by a technology, but such laws must also clarify what is considered safe, prudent action on the part of innovators. In some cases, licensure, certification, and regulatory oversight may be necessary to avoid undue risk. However, as with a reactor core, excessive controls can grind dynamism to a halt. Draconian, ill-defined, capriciously administered civil and criminal liability can kill innovation.

In a nuclear reactor, no one can foresee which neutron will split which nucleus. It’s all a matter of chance and probability. For the same reasons, central planners are generally ill-equipped to determine who can and will innovate the next big thing. No one could have predicted that Alexander Graham Bell, Steve Jobs, Wilbur and Orville Wright, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, Bill Gates, or Jeff Bezos would be world-changing innovators—or what they would innovate. Most likely, central planners would have bet on well-established, well-connected enterprises. There are exceptions—the Manhattan Project among them. But they are exceptions. As a general rule, centralized micromanagement grinds innovation to a halt by making chance synergies so unlikely.

In a reactor, control rods of one material may work well with slow-moving neutrons but not fast-moving ones. 20th century command-and-control regulation may have worked reasonably well on big, heavy, immobile, expensive, traceable, and slowly evolving things. Command-and-control is far less likely to work well on small, light, mobile, cheap, untraceable, rapidly developing things. Regulating smartphone apps or artificial intelligence (e.g., ChatGPT) is not like regulating six-ton, $40,000,000 MRI units.

Political dynamics make it difficult to shift from old to new regulatory regimes. Old regulations come to be seen as ends rather than means. It is as if control rods, rather than fission energy, become the goal of the reactor.

Fear of Pumping in Oregon

Paralytic fear of innovation can blind one to the simple and obvious evidence that lies just beyond your field of vision. Until December 31, 2017, Oregon was one of two states that prohibited drivers from pumping their own gasoline, anywhere in the state. In certain sparsely populated counties in Oregon, gas stations declined to staff their facilities around the clock, so in 2017, the legislature voted to allow self-service pumps in those areas. As of 2023, New Jersey remains the only state that does not allow self-service at any gas pumps.

In 2023, Oregon’s House of Representatives voted to expand self-service pumps to all counties, and the bill is now in the Senate. For those of us in the 48 states that have entered the 21st century, the depth of opposition in the other two is difficult to fathom. Oregon Rep. Anna Scharf said her mother “threatened to stop giving her Christmas presents if she voted” to allow self-service pumps. When Scharf voted for the bill she said, “Mom, if you’re watching, please forgive me.”

Oregonians’ outcry against self-service pumps in 2017 was hysterical, in both the “laughable” and “emotionally overwrought” senses of the word. In a Facebook post that went viral, some vented as follows:

“I don’t even know HOW to pump gas and I am 62, native Oregonian…..I say NO THANKS! I don’t want to smell like gasoline!”

“Many people are not capable of knowing how to pump gas and the hazards of not doing it correctly.”

“Disabled, seniors, people with young children in the car need help. Not to mention getting out of your car with transients around and not feeling safe too.”

The state itself compiled a list of 17 reasons why self-serve gas stations are a terrible idea. These included:

“Appropriate safety standards often are unenforceable at retail self-service stations in other states because cashiers are often unable to maintain a clear view of and give undivided attention to the dispensing of Class 1 flammable liquids by customers;”

“The dangers of crime and slick surfaces … are enhanced because Oregon’s weather is uniquely adverse, causing wet pavement and reduced visibility;”

“The dangers … are heightened when the customer is a senior citizen or has a disability, especially if the customer uses a mobility aid, such as a wheelchair, walker, cane or crutches;”

“The increased use of self-service at retail in other states has contributed to diminishing the availability of automotive repair facilities at gasoline stations;”

“Self-service dispensing at retail contributes to unemployment, particularly among young people;”

“Self-service dispensing at retail presents a health hazard and unreasonable discomfort to persons with disabilities, elderly persons, small children and those susceptible to respiratory diseases;”

“Small children left unattended when customers leave to make payment at retail self-service stations creates a dangerous situation.”

The astounding fact about these histrionics is that they are so easily refuted. In 48 states, the elderly and disabled fill up without incident; residents rarely smell like gasoline; children from coast to coast survive the unspeakable horrors of having their parents get out of the car and fill up their tanks; people manage to find employment other than pumping gas; and remarkably few motorists die in self-service conflagrations.

Presumably, some Oregonians who have driven beyond the state’s boundaries returned alive to share their tales with neighbors. Of course, an out-of-state experience may not be sufficient, as evidenced by this post:

“I’ve lived in this state all my life and I REFUSE to pump my own gas. I had to do it once in California while visiting my brother and almost died doing it. This (is) a service only qualified people should perform. I will literally park at the pump and wait until someone pumps my gas.”

Heaven forfend.

Portions of this segment were adapted from my “The Role of Imagination in Health Care and Gas Pumps,” published by InsideSources in 2018.

Lagniappe

Kids with Horse Sense

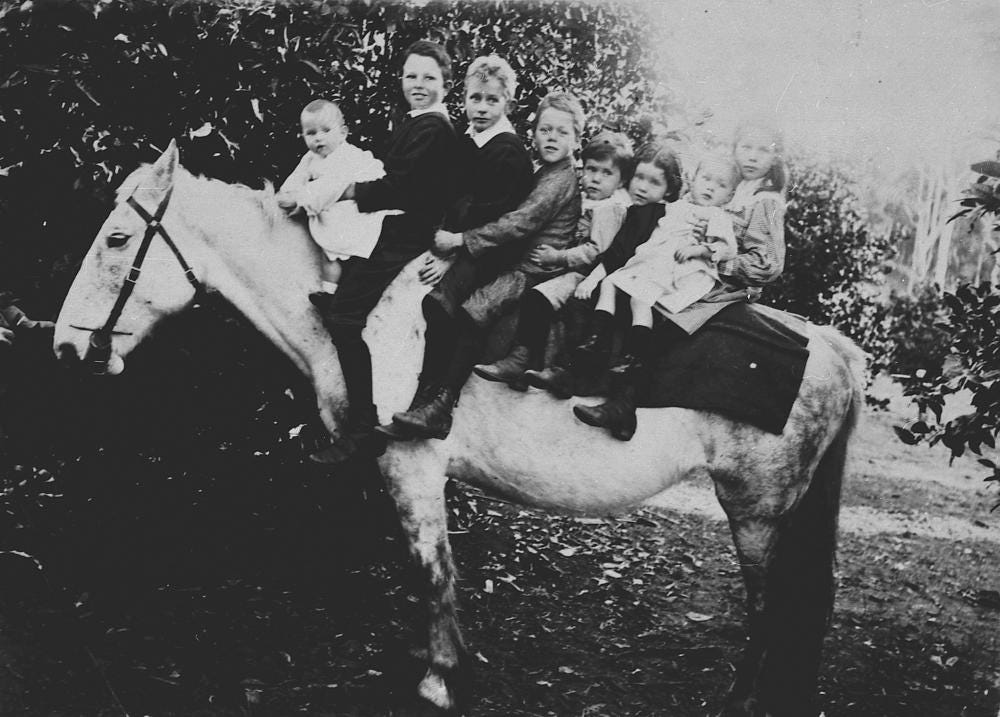

Tautological though it may sound, optimism is a good antidote to pessimism—particularly where kids are concerned. Recently, in “Whence Fall Snowflakes,” I wrote a diatribe against the destruction wrought by severely limiting the space over which children are free to roam, filling their hours with planned events, and hovering in proverbial helicopters above their every waking moment. That essay contrasted contemporary childrearing with the story of the Abernathy Boys, who, at ages 10 and 6 in 1910, rode alone on horseback from Oklahoma to New York City and Washington, DC. Subsequently, below my “20 Job Tips for 2020s 20-Somethings,” I wrote of the optimism I felt after seeing young children showing their prize sheep at a recent Sheep and Wool Festival. In response, two wonderful friends sent me a pair of articles about the maturity and education and responsibility that come from allowing young children to tend to horses.

In “Throwback Thursday: Let Your Daughters Grow Up To Be Horse Girls,” blogger Lauren Sprieser advises, “Parents, let your daughters set goals and reach them. Let them set goals and fail miserably.” She says:

“Let them learn early the joy of dirt under their fingernails and the responsibility of cleaning tack or sweeping aisles. Let them learn that if they don’t do the chores, or if they don’t keep their grades up, they can’t go ride. Let them struggle it out with lesson horses that aren’t very skilled, only to then earn their way to either a horse that is kind and fun to ride, or a horse that is just a big enough monster to keep them humble, and to maim them just a little, but not permanently damage them.”

“Let your daughters grow up in the barn. Let them learn that horses don’t care about your schedule or your plans. Let them learn that buckets need filling and stalls need cleaning, even when it’s raining, even when it’s frozen, even when they have a different idea for how the day should go.”

“Parents, let your daughters make mistakes. Let them enter the show one level too high and get their butts kicked.”

“Parents, let your daughters grow up to be horse girls, because they will learn quickly and repeatedly that life isn’t fair, that hard work is often trumped by Lady Luck, and that every defeat, no matter how terrible, is temporary.”

In “An Open Letter to My Daughter’s Teacher,” Angie Mitchell schools her daughter Anna’s seemingly paint-by-numbers, cookie-cutter teacher on the education that a 6-year-old obtains by caring for horses and competing in events. The teacher had criticized the child’s three absences for equestrian events and had given the mother a list of “Life Skills” that Anna needed to develop. Following were a few of the mother’s responses:

“[The Life Skills document] states she should be zipping zippers. She can put on a pair of leather half chaps by herself. Zipper level: Expert. It states she should be able to snap snaps and button buttons. She can put on her show shirt and jacket, a stock tie, breeches and her helmet. She can also tack up her pony by herself and apply bell boots, open front jump boots and brushing boots, and she knows which ones to use when.

“She’s supposed to know one parent’s phone number, and her parents’ names. She knows the names of the 30+ horses at the barn. She knows what size girth to use, and when to use a running martingale. She knows what hole to put the jump cups for a 2′ course, or a 2’6 course. She also knows how to change her diagonal, turn down centerline, make a 20-meter circle and how to ride a transition.”

“It says I should play “Mother May I” with her. Everything her pony does is because she’s asked, and she knows she has to ask correctly. She weighs 50 lbs. He weighs 700. She has spent hours learning how to not only ask, but listen, when she wants something from him.”

If you want to understand what’s wrong with today’s kids, read both articles—and then read them again. If you’re like me, you’ll finish the articles with more optimism than you’ve had in a while. I suspect that kids who raise horses have a better-than-average chance of being their generation’s innovators.

Robert F. Graboyes publishes Bastiat’s Window, a Substack journal of economics, science, and culture—with an emphasis on healthcare. He is a health economist, journalist, and musician in Alexandria, Virginia, and holds five degrees, including a PhD in economics from Columbia University. In 2014, he received the Reason Foundation’s Bastiat Prize for Journalism. His music compositions are at YouTube.com/@RFGraboyes/videos.

😊

Gas is now a commodity. Some businesses don't get that if you have clean restrooms, well stocked stores, customers will go to your store. And with discount reward programs you can pay less than the posted price for gas. With "fringe" benefits you will go out of your way to buy gas, in my neck of the woods Sheetz usually has pretty clean restrooms, free air for your tires. BP gives 15 cents off per gallon if you have their credit card. I am envious that I don't live near a Buc-ees. When the petroleum companies were more vertically integrated they had company stores which were usually well-run, the independent convenience stores that sell gas are of variable quality today.