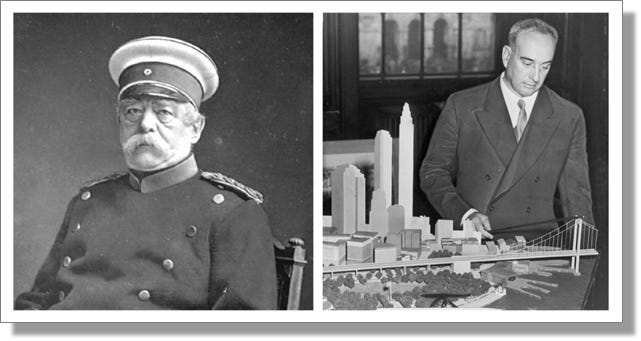

A toxic fragility has settled in over America’s universities, and part of the problem may be the students’ profound lack of mentorship, confrontation, crayfish, and sassafras. For me, the iconic villains are Otto von Bismarck and Robert Moses. Bismarck and his ilk sought to restructure society intellectually. Moses and his ilk sought to restructure society physically. Both succeeded spectacularly, and in recent years, their visions combined like bleach and ammonia to form the suffocating toxic cloud that hangs over American universities today.

One of the great pleasures of my life was teaching thousands of students at five different universities from 1999 to 2017. Thanks to my students, the classes were raucous affairs of intellectual exploration. Classroom discourse was spontaneous and relatively unguarded. I never imposed my views on my students, but I had no fears of expressing my thoughts; the same was true for my students.

Two years ago, a colleague entered a prestigious graduate program. When I asked how the opening days of classes had gone, she described something akin to a dreary Maoist struggle session. Discussion focused on tedious strategies for avoiding the barely discernible microaggressions that would cause fragile classmates and others to crumple into apoplexy. Students dutifully climbed to their particular rungs on the intersectional ladder and admitted the sins that indelibly stain those on their particular rungs. Conversations signaled which sorts of viewpoints would be unwelcome. The best strategy, she thought, was to remain quiet and nod reflexively when absolutely necessary. I wondered how this particular department could have sunk so far, but in the following months, I realized that the problem had suddenly metastasized in universities of every type across America.

In 1987, Allan Bloom (1930-1992) published his seminal The Closing of the American Mind: How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today's Students. So the problem I describe was not new. But college in the time of COVID descended to depths unimagined in Bloom’s time. For me, much of the blame rests on the pedagogy of Otto von Bismarck and the urban design of Robert Moses.

Otto von Bismarck Invents Teenagers

In The Age Barrier, And Its Costs, Glenn Reynolds (@instapun recently asked, “Why are teens, the elderly—and, really, everyone—ghettoized by age?” He wrote:

“… many of our more dysfunctional institutions are sorted by age: Homes for the elderly, public schools, even colleges. This age-segregation is artificial, something that never happened naturally in human society and barely happened at all until fairly recently in historical terms. Age segregation separates people from society, perhaps stigmatizes them, and, I think, harms society too.

It’s probably worst for teens. Putting kids together and sorting by age also created that dysfunctional modern creature, the “teenager.” Once, teenagers weren’t so much a demographic as adults in training. They worked, did farm chores, watched children, and generally functioned in the real world. They got status and recognition for doing these things well, and they got shame and disapproval for doing them badly.

But once they were segregated by age in public schools, teens looked to their peers for status and recognition instead of to society at large.”

John Taylor Gatto (1935-2018) attributed age-segregated schooling in America to 19th century American educators who were smitten by Prussia’s schools. In his The Underground History of American Education: A School Teacher's Intimate Investigation Into the Problem of Modern Schooling, Gatto argued that American ideals were traditionally Athenian and democratic, while Prussia consciously modeled itself on Sparta:

“As the nineteenth century entered its final decades American university training came to follow the Prussian/Spartan model. Service to business and the political state became the most important reason for college and university existence after 1910. No longer was college primarily about developing mind and character in the young. Instead, it was about molding those things as instruments for use by others.”

The Prussian/Spartan model, he argued, relied heavily upon age-segregated schooling that involved classes of an hour or less, followed by ringing bells and regimented changes of classrooms. These practices purposefully stunted the development of critical thinking skills.

In the iconic one-room schoolhouse, with students of all ages jumbled together, the teacher could not run a regimented shop. Instead, older children tutored younger children not only in the proverbial reading, writing, and ‘rithmetic, but also in socialization skills. The Talmud (Taanit 7a) says:

“And this is what Rabbi Ḥanina said: I have learned much from my teachers and even more from my friends, but from my students I have learned more than from all of them.”

In the one-room schoolhouse, the older kids were simultaneously students, colleagues, and teachers. When a 15-year old helped a 9-year-old with multiplication tables or long division, both were learning math, and, as per Rabbi Hanina, the 15-year-old was likely learning more from the experience than the 9-year old. The two were simultaneously teaching one another the virtues of diligence and comity. And importantly, the back-and-forth between informal mentor and mentee instilled critical thinking skills in both. It also fomented friendships across age brackets. The Prussian/Spartan model eviscerated those virtuous social pathways—on purpose. Gatto described the 1907 plan which became the prototype for Prussianized schools in America:

“[E]ast of Chicago, in the synthetic U.S. Steel company town of Gary, Indiana, Superintendent William A. Wirt, a former student of John Dewey's at the University of Chicago, was busy testing a radical school innovation called the Gary Plan soon to be sprung on the national scene. Wirt had supposedly invented a new organizational scheme in which school subjects were departmentalized; this required movement of students from room to room on a regular basis so that all building spaces were in constant use. Bells would ring and just as with Pavlov's salivating dog, children would shift out of their seats and lurch toward yet another class.”

The Prussian model was not accidental—and it was quite effective in its goals:

“As this practice matured, the insights of Fabian socialism were stirred into the mix; gradually a socialist leveling through practices pioneered in Bismarck's Prussia came to be seen as the most efficient control system for the masses, the bottom 80 percent of the population in advanced industrial states.”

The schools were repurposed to produce the human paraphernalia required by the industrial theories of Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford. Again, from Gatto:

“Taylor distilled the essence of Bismarck’s Prussian school training under whose regimen he had witnessed firsthand the defeat of France in 1871. His American syntheses of these disciplines made him the direct inspiration for Henry Ford and ‘Fordism.’ … …

By the 1920s, the reality of the Ford system paralleled the rules of a Prussian infantry regiment. Both were places where workers were held under close surveillance, kept silent, and punished for small infractions. Ford was unmoved by labor complaints. Men were disposable cogs in his machine.”

Still, the 20th century was a vibrant time for intellectual discourse in America. Age-segregated education suffered under some of the toxicity described by Reynolds and Gatto, but by itself, it wasn’t enough to completely stifle creativity and critical thinking. Another profound social change—residential living patterns associated with Robert Moses—supplied the other toxin required to produce the insufferable nature of contemporary academe.

Robert Moses Lobotomizes Bismarck’s Teenagers

Most of us born in early- to mid-20th century America studied in age-segregated Prussianized schools with clanging bells frog-marching us each hour through the hallways. But the Prussian border mostly ended at the edge of the schoolyard. We enjoyed two luxuries practically unknown to today’s children—ample time and expansive geography. By the end of the century, urban designs personified by Robert Moses had converted the hours outside of school into house arrest with tightly supervised furloughs.

From the 1890s on came urban utopianism, where planners imagined cities and metropolitan areas to be canvasses on which to lay their visions for ideal living. There was a dizzying array of visions. The City Beautiful movement unleashed at Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition imagined cities of monumental structures, broad vistas of public space, and wide separation between business and residential districts. The Garden City movement of Ebenezer Howard envisioned highly geometric satellite residential communities dispersed around central cities. The Radiant City of Le Corbusier idealized identical skyscrapers of enormous height, arrayed in perfect rectangular symmetry.

Robert Moses was for decades the great planner of New York City, and his realized visions combined elements of all these movements. Moses, who never learned to drive, romanticized the automobile and effectively denigrated the idea of walking. His designs criss-crossed residential areas with enormous arterial highways, separated pedestrians from the New York’s waterfront, extended freeways to remote suburbs, and bulldozed vibrant neighborhoods with aplomb. The great urban critic, Jane Jacobs, took aim at this vision in her activism and in her masterpiece, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In New York City, she managed to temper some of Moses’s worst excesses. But to a great extent the visions laid out by Moses and like-minded planners set the stage for residential living in present-day America. In doing so, American children lost their time and their geography.

By the standards of 2023, my childhood was a miracle beyond the reach of almost any child today. I grew up in Petersburg, Virginia—then a city of around 40,000 inhabitants. Few streets were wider than two lanes. Most neighborhoods featured pervasive networks of sidewalks. My neighborhood, Walnut Hill, was a bit removed from Downtown, but if one were ambitious, you could walk or bike to the commercial district with no trouble. By the 1960s, shopping malls were within easy reach.

By age 5 or so, I could go around 700 feet to a nearby creek—alone or with friends. There, I spent hours chasing crayfish and minnows, learning to identify plants, making little boats to sail. By age 6, I was allowed to walk, unescorted, the half-mile distance to my elementary school—crossing several streets in the process. By around age 8, I could cross one more street to buy a milkshake or limeade at Gray’s Drug Store. Not long after that, I could go, unescorted, by bus the roughly 2.5 miles to my parents’ store downtown.

By age 9 or so, I could ride my bike a mile or so west to ride up and down on the Civil War entrenchments and throw rocks into Wilcox Lake. Or, I could head southwest, carry my bike across some railroad tracks, and go to the Battlefield Park Swim Club. At that facility, and in the neighborhoods surrounding, I could make friends with kids who did not go to school with me. By 11 or 12, I could pass the swim club and ride my bike an additional 2.5 miles through farmland—alone and incommunicado from morning till dinnertime. Along the way, I could gaze out over farms, explore the woods, and, at the terminus of my early solo journeys, pick pecans on the campus of Richard Bland College. Along the way, I talked to farmers and learned about their lives—which were so very different from mine two miles away. I was precocious and became an expert on trees. (Neighbors would call my parents, asking whether I could swing by to identify trees in their yards.) I ate wild mulberries and honeysuckle. If I came across sassafras, I chewed on the twigs and, now and then, created a handmade toothbrush. My neighbor had a paper route, and I was his substitute; I loved riding alone through the hushed neighborhoods just after dawn.

Oddly, I even have a certain nostalgia for the very least pleasant part of my childhood—being on the receiving end of bullying. I was relatively small, not at all athletic, and laden with both intellectual gifts and social shortcomings. I was a natural victim, but in time, even those challenges became positives. To lessen the risks, I had to mold my personality to deflect bullies. Adults were not around to save me at every turn, and I discovered that a quirky sense of humor and a willingness to stand my ground pretty well put an end to the unpleasantries. Some of the tormentors disappeared from my life, while others, to my surprise, became friends—some of them to this day.

Most of all, these empty hours and wide spaces allowed me to think and to wonder. To consider what was important, what interested me, and to enjoy small, but vitally important experiences. Those memories, those arcing hours of contemplation, gave me practically all that has been good and useful in my life.

These quaint remembrances would would sound other-worldly to most children today. Thirty years after me, 20 miles or so from where I grew up, our son led a far more restricted existence. The design principles dreamed up by Moses and crew had reshaped living. The leafy green suburbs of our son’s youth had no sidewalks and reasonably busy traffic. Even in his teen years, he never ventured more than a mile from home on foot or bike because our neighborhood was boxed in by 6- and 8-lane thoroughfares that even adults dared not cross on foot or bike. When I lamented those barriers to him in a recent conversation, he added, “And what would I have found had I been allowed to cross those thoroughfares?” The answer was, “Nothing but more suburban residential neighborhoods exactly like ours.” No farms, creeks, pecan groves, battlefields, or nemeses to conquer or charm.

Because of this state of affairs, parents began filling their children’s after-school hours with regimented activities. Activities were almost always supervised by adults (often with parents present) who came to micromanage all interactions between the children at those activities. And these trends have become far worse in the three decades since my son was a child.

I have no doubt that this theft of time and space goes a long way toward explaining the ghastly state of American academe today. Today’s students spent their entire childhoods on leashes. They had no place to explore. They had no time for pondering. They had no personal interactions to work out. As a result, they are hopelessly fragile, constantly offended, and utterly dependent. Sadly, colleges and universities gleefully milk this endless supply of stunted maturity.

In 2007, Dr. William Bird, health adviser to Natural England, wrote a report described in David Derbyshire’s: “How Children Lost the Right to Roam in Four Generations.” The essay traced the diminishing roaming spaces of four generations of a British family in Sheffield. In 1919, at age 8, George Thomas could walk alone six miles in order to go fishing. In 2007, his great-grandson Ed, also age 8, could go no farther than the end of his street—a distance of 300 yards—and had little reason to do that.

In 2023, the news in America features child protective services swooping down on diligent parents for daring to allow their children to wander a block down the street or to sit alone for a few minutes in a parked car. Dr. Bird proffered that this ever-tightening constriction poses a profound risk to long-term mental health. Young Ed’s mother said, "Over four generations our family is poles apart in terms of affluence. But I'm not sure our lives are any richer." And as much as I would love to return to classroom teaching, I’m not certain I have the stomach to tolerate a class filled with offspring of Bismarck and Moses.

Lagniappe

The Abernathy Boys

For an extreme example of the possibilities that childhood once held in America, you can do no better than to set aside 28 minutes to watch The Abernathy Boys—a PBS documentary about two young brothers whose cross-country travels alone astonished and electrified America in the early 20th century. This newspaper clipping gives you a hint of their exploits. I tell more details about the Abernathys below, but you may want to learn the facts from the documentary instead of from me. In that case, don’t scroll any farther.

***WARNING: SPOILERS BELOW***

***AGAIN: SPOILERS BELOW***

In a nutshell: Bud and Temp Abernathy were the sons of a U.S. Marshal in Oklahoma who was friends with Teddy Roosevelt and who captured wolves with his bare hands. (YouTube has some videos of him pulling this trick.) In 1909, at ages 9 and 5, Bud and Temp rode alone on horseback from Frederick, Oklahoma to Santa Fe, New Mexico to say howdy to the territorial governor, who was a friend of their dad’s. On the way back, they slept in a cabin occupied by cattle rustlers. Afterward, one of them sent a letter to their father, the marshal, saying (paraphrasing), “I’d shoot you dead on sight, but those are some real good boys you got there.”

In 1910, ages 10 and 6, Bud and Temp rode alone from Oklahoma to New York City to visit Roosevelt, who was just returning from Africa and Europe. Crowds across America gathered in the streets to see them ride by. After visiting with T.R., they rode down to Washington, strolled into White House, where they were introduced to the Cabinet and called President Taft “Bill.” They returned to New York, where their father bought them a small car. The two of them drove unescorted back to Oklahoma.

In 1911, they joined in a challenge—riding from New York to San Francisco on horseback. The contest offered to pay $10,000 (around $300,000 in today’s money) to anyone who could manage the trip in 60 days. Their ride took 62 days, so they didn’t get the prize money. But they had done the trip faster than anyone else in history.

Finally, in 1913, they bought an Indian-brand motorcycle and rode it from Oklahoma to New York with their step-brother. We could use a few more Abernathys today.

Substack is a one-room schoolhouse, and Robert F. Graboyes is the older student showing us important things, and at the same time showing us how joyful it is to see the world anew in the light of those things. Even when the subject matter is dismal, reading Graboyes you come away with some understanding, and that understanding can give birth to a brighter vision for the future. Well done Robert.

It does not reach quite as far back into the past as "The Abernathy Boys" but since you mentioned your lifelong interest in aviation, you might like "Flight of Passage" by Rinker Buck. It is the true story of how Rinker and his brother Kern, then aged 15 and 17, bought and restored a Piper PA-11 Cub Special and flew it across the country. This occurred in the summer of 1966, although Rinker did not write the book until over 30 years later, after he had become a journalist and had children of his own.