NOTE: I’m posting excerpts from my not-yet-published book, “Fifty-Million-Dollar Baby: Economics, Ethics, and Health”—the goal being to edit the manuscript in plain view, informed by your comments, corrections, suggestions, and criticisms.

This is Part 2 of a 3-part series. #1 Fun and Death in Lagos, #2 Checkpoint, Toothbrush, Wind of Change, and #3 Marriage versus Death by Buffalo.

I dedicate this chapter to countless people in eight African countries who welcomed me to their continent long ago. My nostalgia for them and for their lands has never receded.

Just the Basics

In October 1984, I arrived in Nairobi after a 4,200-mile flight from London. Before touring the city, I decided to relax in my hotel room for a bit. International television hadn’t yet reached most of the countries where my job took me, and, as in Nigeria the year before, I was fascinated by local television broadcasts.

The TV screen showed a public event—a temporary grandstand in a field, loaded with suited dignitaries, facing a large crowd of modest-looking people, many in tradtional garb. For perhaps ten minutes, the master of ceremonies introduced the dignitaries—the regional governor, member of Parliament, etc. Then he pointed to a gentleman and said, "And now, it's time for the man we've all been waiting to hear from." I thought the speaker might be a cabinet minister, an agricultural specialist, a naturalist. Instead, he was a dentist, who held up a toothbrush and began to explain the importance of brushing one's teeth every day.

Nairobi is laden with Victorian and Edwardian architecture, alongside handsome modern structures. The architectural gem is the Norfolk Hotel, a sprawling 1904 Tudor complex featured prominently in 1985’s Out of Africa, starring Meryl Streep and Robert Redford. I had dinner there, as did Theodore Roosevelt 75 years earlier. In 1980, a terrorist’s bomb had destroyed a whole wing of the hotel.

The city was aflame with the gorgeous purple-blossomed jacaranda trees. From Chase Manhattan’s office, one could usually see both Mount Kenya, 86 miles north and Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro, 128 miles south. That week, there was a haze, so I saw neither.

A British colleague wanted to take me to a famous Nairobi restaurant called “Carnivore”—internationally famous for its selection of game meats: giraffe, zebra, wildebeest, ostrich, and crocodile. (Game meats have since been outlawed in Kenya.) He asked me to make a reservation for 6:30, so I called. The courteous gentleman taking reservations had a South Asian accent. He said, “So, it is a table for two people at 6:30 p.m., and you are Mr. Robert Graboyes. Is this correct?” I said it was and started to hang up. With the receiver halfway to the phone, I heard him calling sharply, “Sir! Sir!” I brought the phone back to my ear and said, “Yes?” He said, “Sir, are you by any chance a vegetarian?” I said, “Uh … no,” and he said, “Very good sir. We’ll see you at 6:30.” I have pondered for 39 years whether there was an ongoing problem with vegetarians unwittingly making reservations at a restaurant called “Carnivore.”

I told my colleague how charming I found Nairobi to be. He said (paraphrasing):

It is a lovely place, but only because a million or so Kenyans are willing for the moment to live on top of a garbage heap six or seven kilometers from here. The day they decide they’ve had enough of that, today’s Nairobi will cease to exist.

That garbage dump, Kibera, is by some definitions the largest slum in Africa. It was the subject of The Constant Gardner, a John Le Carré novel and 2005 film starring Ralph Fiennes and Rachel Weisz. In part, the film concerns a pharmaceutical company testing drugs on unsuspecting Kibera residents. That plot was based on some actual occurrences—though I can’t say where fact ends and fiction begins.

Incentives Matter

Nutrition and income are two key contributors to health, and my visit to Malawi provided the most tangible illustrations of Economics 101 that I ever experienced. Malawi was much smaller than its neighbors, more densely populated, and poorer. It lacked the rich, deep topsoil of the surrounding countries, and its only freight access to the outside world was via two railroads through Mozambique, where civil war was disrupting rail service.

Malawi’s president, Hastings Kamuzu Banda, was a complex and troubling figure—an American-trained medical doctor who also constructed an elaborate cult of personality. Prospective visitors to Malawi were advised:

“The entry of ‘hippies’ and men with long hair and flared trousers is forbidden.”

But in some areas, Banda understood one big economic incentive better than almost any other African leader of his time. Most African governments were financed by overcharging farmers for agricultural inputs (e.g., plows, fertilizer) and underpaying them for agricultural outputs (crops). Banda was different. For all of his many troubling characteristics (including some terrible economic policies), his government compensated farmers well, and the results (at least during my time there) were striking. A severe drought was desiccating Southern Africa, and the surrounding countries were struggling to produce enough food. Malawi’s problem was that its well-compensated farmers were producing too much food and the country was short on places to store it. (Exports were difficult because of the rail disruptions in Mozambique.) One of my colleagues, also visiting from New York, went to a bar on a Saturday night. The place was empty, and he asked the bartender where everyone else was. The bartender said, “They’re all out farming.” My friend asked how they could farm at night. He said, “They wear miners’ helmets—with a light on front.” In some places, people supposedly planted maize in the thatching of their roofs to leave no wasted space.

My friend took me to a remote camp on the shore of Lake Malawi, then supposedly the only lake in Africa free of life-threatening parasites. And so we swam. Years later, I heard that the parasite-free reputation was erroneous.

A Wind of Change

In the previous installment of this series, I mentioned that I used to tell my students that “there is a slight possibility that my work around that time helped speed up the demise of apartheid in South Africa,” and I put special emphasis on the word “slight.” This section explains what I told them.

In 1960, British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan delivered his “Wind of Change” speech in Cape Town, South Africa. Speaking of colonialism and racial superiority as law, he said:

The wind of change is blowing through this continent. Whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact.

Macmillan was warning South Africa that Britain would not stand by a South Africa continuing its pursuit of apartheid:

As a fellow member of the Commonwealth it is our earnest desire to give South Africa our support and encouragement, but I hope you won't mind my saying frankly that there are some aspects of your policies which make it impossible for us to do this without being false to our own deep convictions about the political destinies of free men to which in our own territories we are trying to give effect.

When I visited South Africa 24 years after that speech, the wind of change had swept across most of the continent, but not South Africa. During my visit, every South African of every racial classification whom I met bent my ear about the country’s racial future. The whites clearly knew the end was coming, but the government was desperately trying to stave off the inevitable. Atop Table Mountain in Cape Town (the most beautiful spot on earth I have ever visited), I looked across the water to Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was long imprisoned (though he had since been moved to a prison in Cape Town itself).

On the plane from Cape Town to Johannesburg, I sat next to a wiry, middle-aged fellow with a dark bronze complexion. He, too, engaged me on the subject of apartheid and, at some point, said, “I’m a white man.” From outward appearance, he certainly was not, but I listened and I wondered whether he lacked self-awareness. Then he pulled out his wallet and showed me his ID card, which said, “white” and continued: “At least this card says I’m a white man,” and he laughed. He was, in fact ridiculing the country’s classification system. He told me that one of his great pleasures in life was going to the whites-only beach at Cape Town and waiting for police to arrest him. Then, he said, he would show the police his ID card. They would walk away, confused and shaking their heads.

South Africa was, in its white precincts, at least, a highly successful, industrial powerhouse—arguably the only First World nation south of the Sahara. In other countries I visited, communications with the outside world were brief and tenuous. I barely spoke at all to my future wife, as international calls were expensive, time-consuming, and often simply not available. International news came from the BBC’s brief World Report. International newspapers did not arrive for days. So, for the only time in my life, I was constantly out of touch with world events. South Africa was different. International calls were expensive, but doable. I was astonished when I realized that CNN was available on a TV in the lobby. Thanks to this, I knew almost immediately when India’s Prime Minister Indira Ghandi was assassinated.

Chase had a substantial, highly profitable lending presence in the country, and my job as the bank’s economist for the region was to assess the safety of that lending—to opine on the likelihood that our loans could go sour. Our borrowers were first-rate enterprises, but I worried that the government’s economic policies might eventually drown even the best-run companies. In particular, lots of people, anticipating post-Apartheid turmoil, wanted to leave the country or, at the very least, wanted their money to leave the country. The government issued increasingly draconian (and dangerous) capital controls—prohibitions against taking funds out of the country.

In my advice to my managers, I suggested that the bank consider reducing its exposure to South African risk. Our borrowers seemed to be doing just fine, but my concern was the possibility of catastrophic change in the near-future. I was only a small voice in the bank, but I offered my opinions.

One afternoon in late July, 1985, my phone rang. It was an acquaintance whom I had visited in South Africa—a sometime advisor to the country’s president, P.W. Botha, who had recently issued a defiant statement to the world. With a worried tone, she said she had heard rumors that Chase would soon cease lending to South African borrowers and was wondering whether I had heard anything. I told her—truthfully—that I was not at the level to hear such news and that I had no idea about the veracity of the rumor.

The next morning, reports hit that news that Chase would no longer lend to South African borrowers. Rapidly, other major banks followed suit, prompting a severe financial crisis in South Africa. Some observers view these events as the moment when the world’s opposition to Apartheid became tangible and irreversible. Mandela would linger in prison until 1990, though conversations began that would eventually lead to a peaceful transfer of power, with Mandela sharing a Nobel Peace Prize with President F. W. de Klerk and, a year later, succeeding de Klerk as president.

As I told my students, I can’t say whether my work at Chase had any impact on the bank’s decision to withdraw from South Africa, though I’ve always hoped it was a contibutory factor. And I can’t say with certainty that Chase’s withdrawal accelerated the demise of apartheid, though I’m pretty confident it did. Nevertheless, I get to enjoy the fact that maybe, just maybe, I helped nudge Apartheid over the cliff just a little faster than might otherwise have been the case. And when looking back across the sweep of my life, that tiny little possibility is something that I savor.

(Note: Any old Chase hands reading this are welcome to correct errors in my recollections—and suggest details that I’ve forgotten.)

An Ounce of Prevention

While in South Africa, a colleague from my bank told me of his recent excursion. He had been posted to Johannesburg for a while but had never visited Botswana, whose capital, Gabarone, was only a five-hour drive away. Outside of South Africa, Botswana was perhaps the wealthiest, most peaceful country in Sub-Saharan Africa at the time. Its first president, Seretse Khama, was the subject of a 2016 biopic, A United Kingdom, starring David Oyelowo, with Rosamund Pike as his British-born wife, Ruth Williams. The film revolved around the real-life political turmoil resulting from their interracial marriage—which Tanzania’s president Julius Nyerere described as, “one of the great love stories of the world”.

Back to my friend: He packed his bags and went across the border, planning to spend the night. After several hours of wandering Gabarone, he decided that it was just a pleasant little place with not much to do. Rather than spending the night, he headed back home. At the border crossing, the guards were suspicious. Why had he come to Botswana, only to turn around and travel back to South Africa, they asked? He didn’t want to tell them that he didn’t find anything interesting, so he said, “My office called me back on urgent business.” Just to be sure, they opened his suitcase, where they found a small leatherine kit that the bank gave each of us for overseas travel. It contained perhaps twenty glass cylinders of pills and powders – Immodium, aspirin, chloroquinine, water purification tablets, etc.

The guards spun their heads and asked, “What is this?” He said, “Those are medications that my bank gives us in case we get sick while traveling.” … “Then you are sick,” a guard said. “In that case, we must quarantine you.” … “No, these are given to us in case we get sick or to keep us from getting sick.” … After a lengthy discussion, it dawned on him that these guards had no concept of preventive medicine. After three or four cycles of this conversation, they relented and let him leave.

Night Road

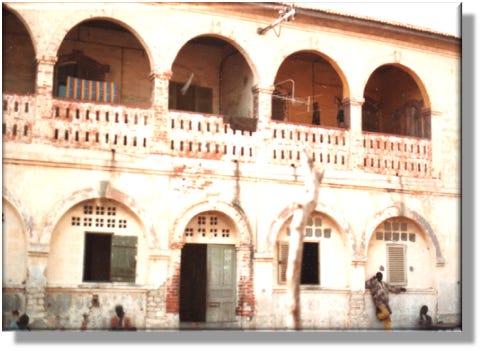

November 6, 1984 my plane from arrived from South Africa at Robertsfield, Liberia. The bank sent a driver for me, with instructions to take me to the U.S. Embassy in Monrovia to watch the 1984 U.S. presidential election results roll in. As we set off, we were stopped at two or three fairly calm police or military checkpoints. We came across one more, only this time, the soldiers were screaming frantically in the local creole and waving machine guns. I told the driver, "Whatever they're asking, the answer is 'Yes.'" He said something to them, and they threw something into the back seat—it was too dark to see what—slammed the doors and waved us on frantically. As we pulled away, I heard a moan from the back. The object, in fact, was a woman deep into childbirth. The screaming, it seems, was the soldiers pleading with us to serve as an ambulance. They had not threatened us with the machine guns. They were merely frantic to help this woman. I told the driver, “Drive as fast as you can without killing us.” We sped down the road in pitch-black darkness, save for our headlights. We got the woman to the hospital in time, thank goodness. The hospital was dark and dingy—like a drug den might look in the U.S.—with a bare, low-wattage bulb hanging from the ceiling. Obviously sick people were in various positions of seating and reclining. They trundled the mother off to a delivery room, and we saw her no more. We went out into the night, headed toward the embassy, and watched democracy do its thing in America. (I have often thought about the mother and her baby and wondered how they fared.)

For the remainder of my stay, I observed a country that everyone knew was descending into chaos and Civil War. Memorably, I stood at one point beneath the statue of Joseph Jenkins Roberts, Liberia’s first president. He was an African American, born into freedom in slaveholding Virginia in 1809. He had lived in my hometown, Petersburg, Virginia before moving in 1829 to Liberia, and I had met at least one of his relatives back home.

Soon after, I said my farewells to that great continent and boarded a plane for New York. After seeing the roadblock and hospital in Liberia, lepers in Dakar, the campfires of the Sahara, the worries about healthcare from my colleagues, the dentist in Kenya, the walkie-talkie in Lagos, the poor and the sick in the streets, healthcare would forever be an interest. The memories of those times have never dimmed.

Lagniappe

While I was writing this essay, my wife, Alanna, happened to send me this gorgeous, inspiring piece of music by American composer Christopher Tin and performed in 2017 by a multilingual choir of amateur singers and a Welsh orchestra. “Baba Yetu” is Swahili for “Our Father,” and the lyrics are simply the words to The Lord’s Prayer in Swahili. The music was written for the video game Civilization IV and was the first video game music to be nominated for and to win a Grammy.

Maybe it's just me but...does the last line in the paragraph Incentives Matter starting with Mozambique need a word or two more?

"While writing this essay, my wife, Alanna, happened to send me this gorgeous, inspiring piece of music ..." Awfully nice of your wife to send you this piece of music while she was writing your column.