If you’re not already a subscriber to Bastiat’s Window, please sign up for a free or paid subscription. (Paid really helps!!) And by all means, share the site and its articles with friends and colleagues.

A thoughtful friend and I recently engaged in a long email exchange over climate change, petroleum, plastics, electric vehicles, cobalt, nuclear power, and, above all, experts and expertise. “Carrie” (not her real name) seems more pessimistic about the state of the world than I am and perhaps more optimistic than I about the capacity of collective action to mitigate problems. At one point, she said: “CO₂ levels are off the charts high, and experts tell us it’s almost too late to do anything about it.” Anticipating my response, she added, “But you tend to dismiss ‘experts.’”

I don’t “dismiss” experts. I listen, weigh their words, and discount those who feign certainty and hurl ad hominem attacks at those who disagree. I recoil at the expression “experts agree,” and even more so when it’s festooned with faux precision (e.g., “97 percent of experts agree.”). History’s greatest outrages were fueled by agreement among experts and intolerance of dissidents.

Perhaps it’s useful to differentiate “expertise” from “scholarship.” Expertise (as seen on TV!) often combines the trappings of scholarship with a marketing department, lobbying shop, and protection racket. (“Nice tenure-track professorship you got there. Be a shame if anything happened to it.”) Scholarship, in my mind, is more detached, detailed, and skeptical.

Skepticism, however, is not nihilism. How I vote, what I drive, where I live, and what I eat are all guided by perceptions about climate and environment, and there is nowhere for me to obtain those perceptions outside of the cacophony about me. I offer no opinions here on environmental science, where I am neither expert nor scholar. I am happy to explain how my studies of economics, science, and history have nourished my skepticism in today’s Age of Adamance. I’ll summarize my thoughts as seven rules.

Thanks to Carrie, who kindly allowed me to mine our conversation. I hope to fairly represent her views and preemptively apologize for any failure to do so.

[1] Celebrate diversity (of thought).

For my stereotypical expert, the above diagram is a nightmare; for my stereotypical scholar, it’s a joy—the essence of science. It offers the expert no TV soundbite, political agenda, or social wedge. It offers the scholar a lifetime of drilling deeper into the data, finding the practical applications, and upending prior beliefs with newer evidence; it reminds us of the fragile and tentative nature of all scientific findings and the imperfections of cognitive processes.

In “This is Why You Shouldn’t Believe that Exciting New Medical Study,” Vox writer Julia Belluz used a version of this diagram to argue that journalists and readers become overly excited by new studies, spurred on by “overhyping” scientists “who are under their own pressure to attract research funding and publications.” I’ll quibble with Belluz’s lament that journalists covering science “don't wait for scientific consensus.” History shows that consensus itself can be a self-reinforcing menace to science and society.

In the 20th century, expert consensus fueled the atrocities of eugenics and spurious explanations of autism, ulcers, and prion diseases. This diagram indicates “consensus” on only one food—bacon, where all the studies are on the “causes cancer” side of the chart. Another Vox article, “The Bacon Freak-out: Why the WHO's Cancer Warnings Cause So Much Confusion,” took the World Health Organization to task for its stridence in declaring, “there is convincing evidence” that smoked meats cause cancer. The author, Brad Plumer, said the warning induced “sloppy journalism and needless panic,” with news outlets (including PBS) equating the dangers of bacon with those of smoking. Plumer called that comparison “wildly untrue,” adding that, “Munching on the occasional bacon strip simply isn't that dangerous.”

[2] Follow the Goldin (not Golden) Rule.

In discussing petroleum usage, Carrie and I had the following exchange (edited for brevity):

CARRIE: “My pet peeve is Nestle selling bottled water in plastic to people who will consume it in their air-conditioned buildings, literally standing 10 feet away from a water fountain. Fix THAT!”

ME: “My uneducated guess is that plastic water bottles are a small pimple, if that.”

CARRIE: “Don’t guess—Google. ‘In fact, it's estimated 1.3 billion plastic bottles are used each day across the world, which is about 1 million per minute.’ … [I]t’s a massive waste of petroleum, (and diversion of water) but the corporations raking in the money don’t care.”

I immediately thought of Harvard economist Claudia Goldin, who says her students often cite large isolated numbers with lots of zeros as proof of something or other. (e.g., “That cost six BILLION dollars!!! That’s “6” followed by NINE zeros.”) Goldin’s response is to pause and ask, calmly, “Is that a big number or a small number? And compared to what?” So, I asked myself, “Is 1.3 billion bottles a day a big number or a small number—and compared to what?” Googling and a few back-of-the-envelope calculations yielded the following:

1.3 billion water bottles a day means around 500 billion bottles per year, globally.

Americans use 50 billion bottles. It takes 17 million barrels of oil to satisfy America’s demand for bottles. So, 1 barrel of oil yields around 3,000 bottles. (3,000≈50b/17m)

Thus, making 500 billion water bottles require around 167 million barrels of oil a year. (167m≈500b/3,000)

Total annual world oil production is around 93.9 million barrels per day, or around 35 billion barrels per year. (35b≈93.9m×365 days)

So, plastic water bottles consume a little less than 0.5% of the oil produced. (0.5%≈167m/35b)

That’s lots of zeros, but if you eliminated all plastic water bottles, you’d reduce global oil consumption by less than 0.5%. If you wish to cut petroleum consumption, perhaps there are better places to look than plastic water bottles.

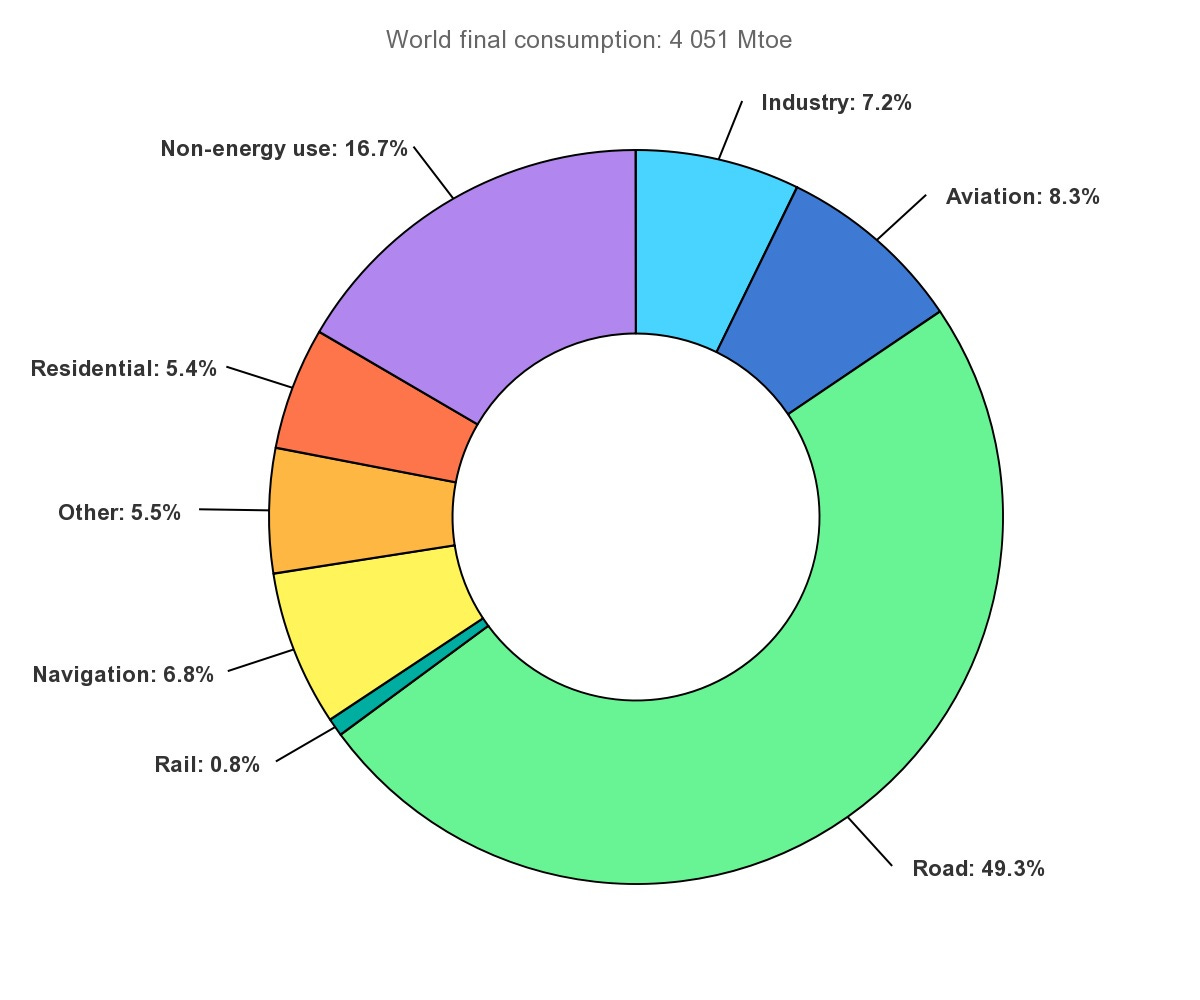

This chart says that transportation accounts for 65.2% of oil consumption. So, cutting transportation by less than 0.8% would reduce oil consumption as much as eliminating all plastic water bottles. (0.8%≈0.5%/65.2%)

Powering the Internet requires between 200 and 400 terawatt-hours of energy per year. That’s equivalent to between 120m-240m barrels of oil—compared to 167m barrels for plastic water bottles.

Bitcoin—one company—consumes 127 terawatt-hours of electricity per year in its crypto mining operations. That’s the equivalent of 75 million barrels of oil—45% of the amount of oil used in global production of plastic water bottles.

Carrie spoke of people standing by water fountains in air-conditioned buildings, but that may not be the typical bottled water user.

Americans consume 50 billion plastic water bottles per year. But that’s only 10% of world consumption. (10%=50b/500b).

China, India, Mexico, Indonesia, Thailand, and Brazil are also among the top 10 consumers of plastic water bottles.

Perhaps most of these bottles are used in places where water is neither clean nor accessible, and where plastic water bottles can be the difference between sickness and health, or even life and death. And, indeed, another Google search brings up a report suggesting that: “Surging global bottled water consumption reflects the failure by governments to improve public water supplies.”

I’m not saying Carrie is wrong. I could drink more tap water and less bottled water. But if petroleum consumption is our concern, then perhaps we should check our Facebook and Instagram accounts less, mine a bit less cryptocurrency, and cut down on our bucket-list junkets to New Zealand, Kenya, Nepal, and Japan before we ask people in poorer countries to drink dirty, parasite-laden water.

EXTRA CREDIT HOMEWORK EXERCISE: Calculate how many plastic water bottles you could make with the oil burned by one movie star flying his Learjet from L.A. to Davos, Switzerland and one politician flying his jet from Washington, D.C., to Davos so that they might chat over canapés about climate change.

[3] Despair less, rejoice more.

At one point, Carrie said:

“We are drowning in [plastics] … I despair for the future of the human race.”

I would say she and I differ in that when we look at the world, she sees a glass (or plastic bottle?) half-empty, whereas I see it is as half-full. I commented that:

“All in all, I think humanity has done quite well over the past two centuries. There are problems to fix, but I’d rather be living in 2023 than in any other year in human history.” … … From cave days till not much more than 200 years ago, the real income of human beings was static and paltry—the equivalent of around $300-$500 per year in today’s money. Life expectancy was in the realm of 30 years—and you suffered all sorts of grievous illnesses during those years; child mortality was perhaps 25% and 50%. One of the most common causes of death was murder. Economist/historian Robert Fogel attributed our massive increase in life expectancy and income to greater caloric intake, especially in the first 4 or 5 years of life—including those critical nine months spent in the womb. In “Growth as Mother of Life, Health, and Contentment, I argued that, “It's fashionable to question whether GDP growth is good, but history says otherwise.”

To make that last point, I quoted World Bank President Jim Yong Kim, who said in 2018:

“Over the last 25 years, more than a billion people have lifted themselves out of extreme poverty, and the global poverty rate is now lower than it has ever been in recorded history. This is one of the greatest human achievements of our time.”

I added:

The technologies and bountiful food that will hopefully allow you to live to 80, rather than having lain in your grave for the past 40 years, could not have existed without two hundred years of coal and petroleum energy.

[4] Save time, not stuff.

Carrie wrote more on plastics in general.

“Cheap plastic has led to a disposable culture of clothing, toys, and other commodities. Kids don’t need all that junk and they certainly didn’t have it when it was made from trees.” … “We are drowning in [plastic], and I sincerely doubt any government has the power or fortitude to stop our overuse of the material.”

When I visit homes cluttered with primary-colored objects, I might agree with Carrie on kids and plastic junk. But the idea of governments exerting “the power or fortitude to stop our overuse of the material” deeply discomforting. I don’t want McMansion-dwelling, jet-setting D.C. junketeers to command people to stop buying Legos and Fisher-Price toys.

Carrie is not alone in lamenting the “disposable culture” and longing for bygone days when we fixed our broken TVs rather than junking them. As noble as that nostalgia may sound, it misses one of the most important concepts of economics—opportunity cost. As we have grown wealthier and more efficient, the real value of our time has risen, and the real value of stuff (like televisions) has fallen. Our time is the ultimate resource. I could go on, but the above John Candy video, “Roy’s Food Repair,” says it better than I possibly could. Note the cost calculations that Candy undertakes with Paul Simon.

[5] See the unseen.

This publication is called Bastiat’s Window in honor of Frédéric Bastiat’s Parable of the Broken Window, which crystallized the distinction between the seen and the unseen in economics and in life. (It’s a beautiful allegory, so read it.) Carrie and I discussed the push to replace internal-combustion-engine vehicles with electric vehicles (EVs). (I’m not sure whether she favors rapid EV mandates.) My responses covered two separate groups of concerns:

Will EVs reduce pollution and energy usage? Problems include:

EVs are heavier than internal combustion vehicles, so they wear down roads more quickly. This necessitates more frequent road repairs, which demand more asphalt, which is made from … oil.

Heavier EVs mean that tires will wear out more rapidly, thus requiring more frequent purchases of tires, which are made from … oil.

EVs must be recharged, and the power plants that generate the electricity mostly run on … oil. Or coal or natural gas. (Wind, solar, and nuclear are discussions for another day.)

What are the hidden costs—the unintended consequences—of EVs?

As EVs grind down tires more rapidly, it turns out that this produce fine particulate matter that goes into the air we breathe. This pollution may be worse for the environment than gasoline and diesel emissions.

Electric batteries have sharply increased world demand for cobalt and lithium. Practically speaking, this means mining under near-slavery conditions in China and Congo.

Battery fires have increasingly become a grave danger. (Recently, headlines blared a tragic apartment fire in New York City when batteries for scooters self-combusted.)

Should we speed up or slow down the push for EVs? Again, I’m not the one to ask. I’m a consumer, not a producer, of information on energy. The only advice I’ll offer is that if an “expert” isn’t addressing these prickly questions, that expert may not be worth listening to.

Recently, a Bastiat’s Window reader posted three “Laws of Unintended Consequences”:

They exist.

They are rarely desirable.

They are often far more significant than the intended result.

[6] Save the whales!

Carrie wrote:

“When I think of the FAR future, I think, someday we’ll be out of petroleum, and then we won’t be able to make any more plastic! And our great-great-great grandchildren will be hoarding precious plastic bags.”

I noted that 19th century people worried that one day, we would run out of whale oil, and then our houses would go dark and our machinery would lack lubricants. Instead, as prices rose, people stopped killing whales and started drilling for petroleum.

I mentioned a book co-written decades ago by two scholars, one of whom was a valued colleague. In The Doomsday Myth: 10,000 Years of Economic Crises, Charles Maurice and Charles Smithson documented humankind’s long history of worry over running out of things. Thomas Malthus worrying that we’d run out of food, the New York Times fretting in 1900 over “The End of the Lumber Supply.” The whale oil crisis. The Great Timber Crisis of the 1500s. Fears in Ancient Greece that shipuilding would eradicate all timber supplies in that region. Fears that when bronze supplies were depleted, we’d have no more metals. Ancient flint crises. In every case, as long as markets were allowed to function, innovators discovered or devised substitutes, and the crises passed. If you’re unfamiliar with the 1980 Paul Ehrlich-Julian Simon wager.

[7] Remember your amnesia.

There’s a well-known public intellectual (whom I won’t name) who is much-read and often-quoted. Long ago, I noticed that whenever he discussed a subject I knew well (e.g., economics or healthcare), I found him unrelentingly clueless. But when I read his words on some subject where I had no intimate knowledge, I found him interesting and insightful. At some point, it hit me that, “If he’s so wrong on things I know, maybe he’s equally dim on things I don’t know.”

That epiphany, it turns out, has a name: the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect, named for Nobel physicist Murray Gell-Mann. The idea comes from writer Michael Crichton, who described the phenomenon this way:

“You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray’s case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the ‘wet streets cause rain’ stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.”

Remembering the Gell-Mann Amnesia Effect helps reduce my consumption of expert-driven nonsense. If some publication or individual author spouts inanities on a subject I know well, then I pay little attention to what they say on subjects where I lack knowledge. For example, if your writing or your publication tell me that inflation is caused by greedy corporations and profligate individuals (rather than by monetary policy), then I will automatically ignore anything you say about CO₂ emissions or the Greenhouse Effect.

Lagniappe

Finally, just to make clear that, like Carrie, I’m no less concerned about pollution, I’ll offer Tom Lehrer’s song, “Pollution” from his 1965 album, That Was the Year that Was.

Excellent piece! One thought to add: the monoculture doesn't agree with experts, it agrees with the "right" kind of experts. See, for instance, the reaction to the Great Barrington Declaration, when experts with all the right credentials (Harvard, Stanford, Oxford) were dismissed as extremists because they had the "wrong" policy prescription.

> Skepticism, however, is not nihilism.

I love this! Too many people use the term "question" as synonymous with "deny." But it's perfectly fine to question and investigate your beliefs and ideas, and end up honestly coming to the conclusion that they're OK and valid after all.