NOTE: I’m posting excerpts from my not-yet-published book, “Fifty-Million-Dollar Baby: Economics, Ethics, and Health”—the goal being to edit the manuscript in plain view, informed by your comments, corrections, suggestions, and criticisms.

This is Part 1 of a 3-part series. #1 Fun and Death in Lagos, #2 Checkpoint, Toothbrush, Wind of Change, and #3 Marriage versus Death by Buffalo.

I dedicate this chapter to countless people in eight African countries who welcomed me to their continent long ago. My nostalgia for them and for their lands has never receded.

In my professorial days, I regularly told my students two stories: First was that I once had to choose between getting married and being trampled to death by a buffalo in East Africa. Second was that there is a slight possibility that my work around that time helped speed up the demise of apartheid in South Africa. The first is a tongue-in-cheek retelling of an actual occurrence. The second is entirely serious, though the word “slight” is essential to its veracity. I’ll tell the apartheid story in Part Two of this three-part series. And I’ll tell the buffalo story in Part Three. Both should be posted later this week.

This series consists primarily of a series of remembrances of my travels in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1980s—images of poverty and sickness that helped ignite my interest in healthcare and, eventually, turn my career in that direction. The economics of healthcare has been my principal concern since 1994, but from 1983 to 1988, I was Chase Manhattan Bank’s economist for Sub-Saharan Africa. On my business trips to that continent, totaling around three months, there were constant reminders of the fragility of health and life and the proximity of sickness and death.

The depth of Africa’s impact on me derived from the narrow perimeter within which my life was confined before my 1983 flight to Lagos, Nigeria. From 1954 to 1965, I never once ventured outside of a quadrilateral whose corners are Virginia Beach (VA), Philadelphia, Baltimore’s western suburbs, and Greensboro (NC)—an area that is probably smaller than my native Virginia alone. Before moving to New York City to study at Columbia in 1980, there were only five brief sojourns outside of that quadrilateral: the New York World’s Fair in 1965, car trips to St. Louis in 1971 and Miami/Key West in 1972, and returns to New York in 1978 and 1980. From 1980 to 1983, I spent a fair amount of time in New England, including two summers in Great Barrington, Massachusetts and several trips to Boston and Maine. For the late 20th century, I was no one’s idea of a well-traveled man.

Life, Death, and Music in Lagos

For a small-town provincial like me, there is no more jolting an introduction to world travel than a solo trip to Lagos, Nigeria—one of earth’s most chaotic cities. In 1983, I got my first passport, and Chase flew me to Paris, followed by a southward plunge to Lagos. The flight was 10 or 11 hours, most of that over earth’s most barren terrain. The Sahara stretched to the far horizon, with only an occasional hint of human habitation. The film offering that day, Flashdance, seemed utterly incongruous with the surroundings. It’s a fine film, and I watched with interest, though half the time, I was looking eastward as the shadows below grew longer and longer. Toward the end of the film, darkness descended, and I could see campfires, miles and miles from one another, dotting the landscape as far as the eye could see. Who was down there and how they lived in such a place was unfathomable to me. At some point during or after the flight, I thought, “What if someone sitting beside one of those campfires becomes seriously ill?” And I pretty well knew the answer.

The next evening, sitting in my host’s apartment, a colleague and I watched the evening news. There was a half-hour of local stories. In the middle, a cheerful young newscaster did a public service announcement asking viewers not to ignore dead bodies lying in the streets but, rather, to report them to the authorities. My colleague, who was from Ethiopia, turned to me with raised eyes and said, “I guess we’re not in New York.” A few weeks after I returned to New York, the memory of that comment seemed ironic when three Columbia University students found a discarded carpet a block from my apartment, carried it back to their dorm room, and discovered a bullet-riddled body rolled up inside of it. (They did report it to authorities.)

At the end of the Lagos newscast, after all the local stories, the anchor said that “in other news” the United States and the Soviet Union had come to some sort of accord regarding nuclear armaments. My Ethiopian colleague said, “Priorities are different here.” We didn’t realize it at the time, but the U.S. and U.S.S.R. had potentially come close to nuclear war just days before our conversation.

An American living in Lagos told me he knew a European whose arm was badly injured in a machete attack by robbers. The injured man was told to apply a tourniquet and fly to London for treatment. The long plane ride, he was told, would pose less risk than local medical treatment in Lagos.

One night, my host had to go out and leave me alone in the apartment that Chase rented for him. The apartment was attractive, but not extravagant. Because of a screwed-up exchange rate, the bank paid (I was told) $50,000 per month year in rent (nearly $150,000/monthyear, in today’s dollars). But for four years, the bank had been unable to get a landline phone installed in the apartment. (Cellphones didn’t exist yet.) Before he left, my host handed me a walkie-talkie. If I needed police or medical attention, he said, I should use the device to seek help from the Marine guards at the U.S. Embassy.

Lest any reader get the wrong ideas, it was clear to a visitor like me that, despite the chaotic atmosphere, Nigeria was bursting with ambitious, high-achieving people with powerful intellects. In 2023, research suggests that Nigerian-Americans are the single most educated ethnic group in the United States.

the educational attainment of second-generation Nigerian Americans exceeds other second-generation black Americans, third- and higher generation African Americans, third- and higher generation whites, second-generation whites, and second-generation Asian Americans.

The same driving intellectual foment was obvious in those I met in Lagos. At the same time, immense poverty and physical disabilities were there in plain sight.

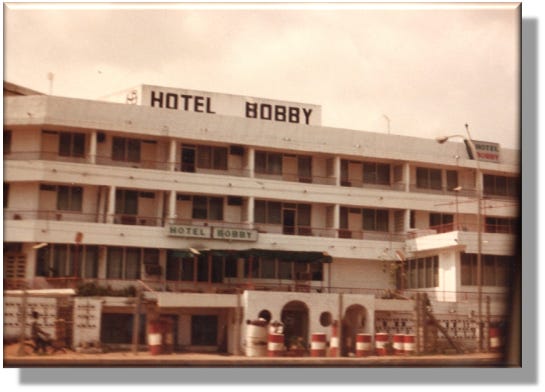

After a week or so in Lagos, it began to remind me of New York City—crowded, turbulent, raucous, and bursting with culture. Driving to the airport, I snapped the photo above, solely because, as a child, I was known as “Bobby.” Decades later, I wondered whether Google might have anything on the place. To my surprise, it turned out that the Hotel Bobby was the hot center of Nigeria’s world-class music scene. The hotel’s owner, Bernard Olabinjo "Bobby" Benson was a musician who revolutionized Nigeria’s Afro-Caribbean highlife music. His hotel was where one went to hear the new sound—like Benson’s hits, “Niger Mambo” and “Okokoko.” Benson had died six months earlier, but I did get to hear a fantastic concert of highlife at the Nigerian National Museum. Afterward, I raved about the city’s cultural scene to an American living there. He nodded and said, cheerfully, “Lagos is great fun as long as you don’t need police assistance or medical care.” I later learned that his only child had died of a bacterial infection that would have been trivial back in the States.

Flying from Lagos to Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, I had what, as of today, was one of the two most turbulent flights of my life. Over Ghana, we ran into a tropical depression, and the plane began to bounce wildly. Like me, the other passengers, mostly Africans, fell utterly silent with dread. Finally, we hit what stands as the biggest air pocket I’ve ever tumbled into. Just as began our abrupt plummet, some guy at the back of the plane let out a big “YEEEE-HAAAA!” and everyone in the plane burst into explosive laughter. They all started talking again, even though the turbulence continued for a while. I looked to see the source of the rodeo cry and saw a white guy with a big, satisfied-looking smile. I made a mental judgment about his origins and said to myself, “Thank God for Texans.”

One City, Two Worlds

A week or two later, I visited Dakar, Sénégal—a graceful seaside city that was once the capital of French West Africa. Sénégal’s first president after independence was Léopold Sédar Senghor, a poet and philosopher who was later a member of l’Académie Française, the organization that governs the French language. Dakar sits on the Atlantic—right at the westernmost tip of Africa. As a child, I had often listened to a Dakar station on my father’s short-wave radio. At the time, it had seemed impossibly distant—as if in a different solar system. But there I was.

For me, every experience in Africa was just slightly askew. I stayed at the Hotel Teranga (now the Pullman Dakar Teranga) near the fashionable Place de l’Independence. I stretched, pulled the drapes, and gazed on Gorée Island and, behind it, a gorgeous orange sun half-risen over the Atlantic horizon. Then it hit me. Dakar is the westernmost tip of Africa. Why, then, was the sun rising over the thin line of endless ocean? Later, I found a map and realized that Cap-Vert (the Cape Verde Peninsula) is shaped like a fishhook, and my hotel room was on the eastern side of the barb of the fishhook—overlooking not the Atlantic, but rather an enormous bay defined by said fishhook.

Dakar is a popular vacation destination for Europeans—and particularly for the French. Chase Manhattan had a modest, but handsome office in a fashionable precinct. To enter the door of the bank, one had to walk past a phalanx of lepers and people with other physical deformities, begging on the sidewalk.

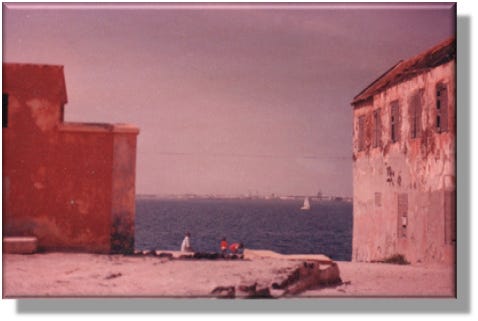

In my off-hours, I did a pilgrimage to Gorée, a beautiful island with a melancholy history, as described by UNESCO:

From the 15th to the 19th century, it was the largest slave-trading centre on the African coast. Ruled in succession by the Portuguese, Dutch, English and French, its architecture is characterized by the contrast between the grim slave-quarters and the elegant houses of the slave traders.

An estimated 10,000,000 to 15,000,000 men, women, and children were exiled into slavery from Gorée. As described by the African American Registry®:

Human beings were chained and shackled. As many as 30 men would sit in an 8-square-foot cell with only a small slit of the window facing outward. Once a day, they were fed and allowed to attend to their needs, but still, the house was overrun with the disease. They were naked except for a piece of cloth around their waists. They were put in a long narrow cell to lie on the floor, one against the other. The children were separated from their mothers. Their mothers were across the courtyard, likely unable to hear their children cry. The rebellious Africans were locked up in an oppressive, small cubicle under the stairs; while seawater was sipped through the holes to ease dehydration.

That article focuses on the “door of no return,” pictured above—a bleak stone portal through which countless Africans passed as they boarded slave ships bound for the New World. The experience was sufficiently moving that I returned to the island a year later.

Colonialism, UN-Style

Some months after my return from Nigeria, Côte d’Ivoire, and Sénégal, a bank colleague and I had lunch with an earnest young bureaucrat from Ghana. He told us that, "The problem with West Africa is that we have no entrepreneurs." I looked quizzically at my colleague and then asked, "Why would you say that? In my travels, I concluded that everyone in West Africa is an entrepreneur." They leave their day job at the bank and use their cars as taxis in the evening. They bake bread in the evening and have their mothers sell it on the street the next day. Many set up stands on the street to trade foreign currencies—even around the front door of the central bank. Everyone seemed to have two or three jobs. The young Ghanaian was adamant: "No! We have no entrepreneurs in West Africa,” and, to add authority to his claim, added, “Did you know that the United Nations established an office in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire, specifically to search for entrepreneurs in West Africa? And after three years, they closed it because they couldn't find any." My friend and I smiled. I turned to our young visitor and said, "I have no trouble believing your story. But I suspect it tells us more about the United Nations than it does about West Africans."

I like the article very much, especially the final part. I could add some context to the perspective that there are no enterpreneurs in West Africa. Over the past months in Gambia, I heard this phrase many times, mainly from the Gambians themselves. By this, mainly they meant the lack of investors and inability to grow their business due to perceived lack of financing. However, in almost all cases I found that it is not lack of funds but rather lack of business attitude and goal-oriented mentality that is hampering the business to grow. In one case I may have been able to help the business owner ramp up without financing. In all other cases I failed to convey the message.

Thanks. Sorry but made another comment on the second chapter as well. That's just me, a Chase trained English Major. When I was in college, my uncle who was head of the old Bank Of Manhattan international department advised me to forget finance and major in English. Most bankers can't write a coherent sentence he said. Looks like you took his advice as well. Good reading you.