Hey, Siri — What Is Hell?

How privacy has vanished in a No Exit world of constant, relentless interconnectivity

Portions of this essay were adapted from my “Digital Life — No Room to Hide,” published in 2017 by InsideSources.

PRIVACY TO プライバシー

Privacy, it turns out, may have been a vanishingly brief phenomenon in human history.

In No Exit, Jean-Paul Sartre said: “Hell is other people.” (The French title and quote are Huis Clos and “L’enfer, c’est les autres.”) In the play, three men a man and two women are sent to Hell, but rather than finding flames and torture devices, they find themselves seated in an elegant room, outfitted in Second Empire style. But—and this is the Hell part—they will spend the rest of eternity together in this room, never out of sight of one another. Not a moment of privacy until the end of time.

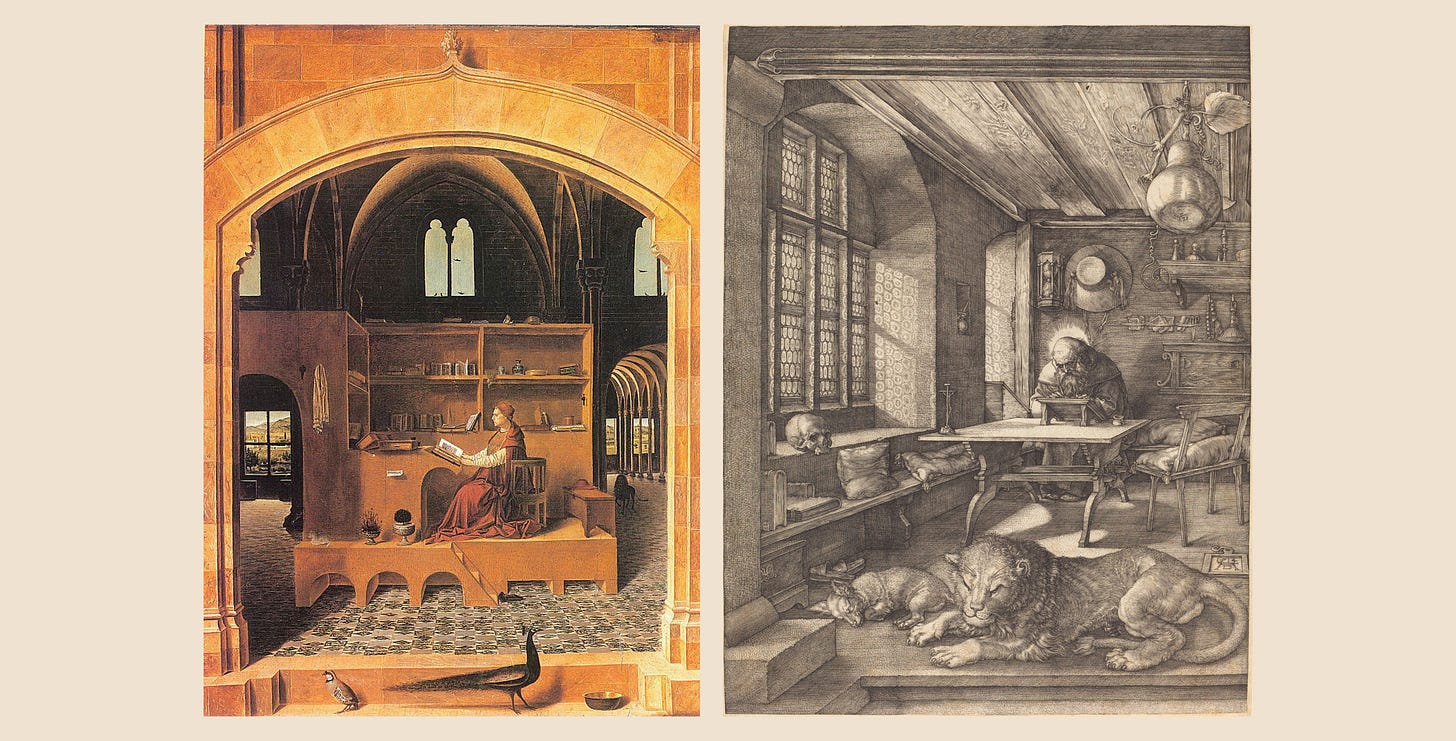

In Home: A Short History of an Idea, architecture professor Witold Rybczynski discusses the idea of privacy—the surprisingly recent idea of getting away from other people. By way of illustration, he discusses two paintings titled St. Jerome in His Study. Antonello da Messina’s c.1475 version shows a distinctively non-private study. In sharp contrast, Albrecht Dürer’s 1514 version shows a study that meets our modern idea of privacy—a closed, rather cozy space, sequestered away from other people. (The lion sleeping on the floor is a tad unconventional, but hey.) Rybczynski notes that the idea of rooms in which to be alone had only appeared a century before Dürer’s work—and that they were called “privacies.” He also notes that:

“The concept of privacy is absent in many non-Western cultures, notably Japan. Lacking an indigenous word to describe this quality, the Japanese have adopted an English one—praibashii.”

For those interested, the Japanese word for privacy is プライバシー. And, BTW, Rybczynski notes that, unlike my own header graphic, Dürer’s engraving of St. Jerome includes no bookshelves because, he says, they hadn’t been invented yet.

SIRI MEETS SARTRE

The interconnected world is larger than a single room, and its population is greater than three, but still, we today feel a profound loss of privacy. There is a sense that one can never escape the eyes and ears of those around us—and it’s unnerving. A profound and devastating 2025 Netflix miniseries, Adolescence, tells of a troubled English boy, accused of murder, who spends much of his time as alone in his room as St. Jerome but who, thanks to the Internet, has no privacy there—and affords no privacy to others.

Your photo, address, phone number, age, marital status, home value, employment history, arrest record, friends’ names, and more are easily available to strangers on other continents. Somehow, someone in Houston or Mumbai knows exactly which car you drive and interrupts your dinner to warn you that its warranty is about to expire. Alexa is listening and Siri offers unsolicited advice. The loss of privacy is represented in the following social media meme:

While writing this essay, my wife asked what my topic was. I responded, in a fairly soft tone of voice, by simply telling her the title—“Hey Siri—What Is Hell?” Unexpectedly, a second later, across the room, a cheerful British lady shouted from my iPhone, “HERE’S SOME INFORMATION ON HELL!!!”

LONG AGO AND FAR AWAY

I would never voluntarily return to the pre-connected world where one spent much of life incommunicado, with whereabouts unknown and unknowable to employers and loved ones. But those times of isolation had their charms and virtues.

In “Whence Fall Snowflakes,” I recalled fondly the solitary all-day bike rides that carried me through farms and woodlands south of my town from around age 11 on. From the moment I left our driveway, my parents had no idea where I was from morning till suppertime. They had no way to find out, and I had no way to tell them, save for banging on the door of some farmhouse and asking to use the phone (which I never did). No doubt, bad things could have happened to a child in such circumstances, but I never knew anyone who suffered death or serious injury on such excursions. And those long hours of solitude gave me ample opportunity to think, to plan, to hope, to dream, and to build the person I am sixty years later.

Two decades later, the solitude of my bike rides was writ large on a trip that took me nearly 8,000 miles from home. In 1984, during a six-week, six-country business trip through Sub-Saharan Africa, I communicated little with my then-fiancée. International calls took hours to make, and the high long-distance charges limited them to a very few minutes. Email didn’t exist. World news was hard to find. Financial transactions required cash—stuffed inside a money belt inside my pants. One day, a colleague took me to a “resort” in Malawi—a few spare cabins on the shores of Lake Malawi. As the sun set, it occurred to me that I was two-thirds of the way around the world from home, and no one but my traveling companion had any idea where I was. The remoteness and isolation was both unsettling and exhilarating.

STEP BY STEP

A string of memories reminds me how digital technologies ended the solitude and anonymity of that world—mostly for the better, but not entirely.

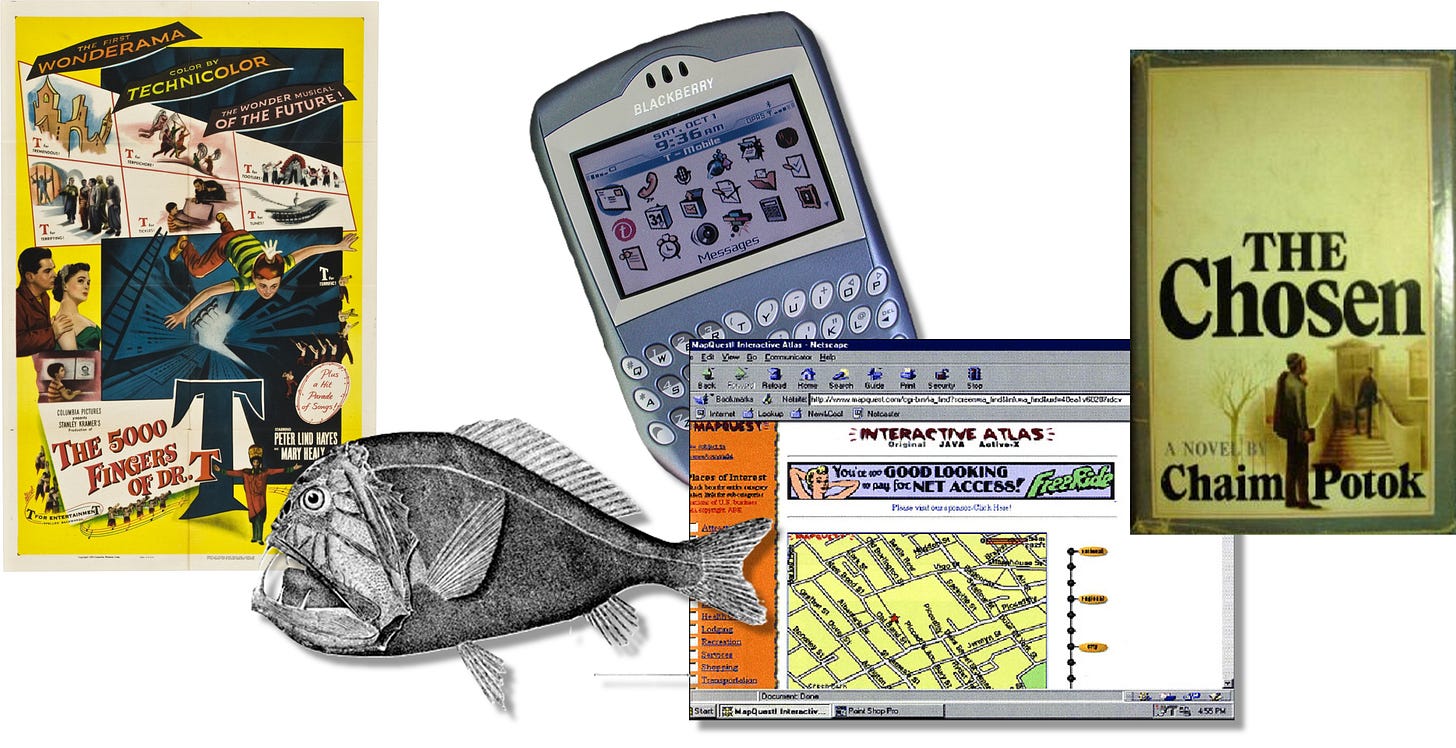

One night in 1996, beginning around midnight, my wife and I watched a peculiar 1953 film: The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T—the only live-action film written by Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel). The young star looked vaguely familiar. After a few guesses, my wife settled on “Jeff Miller” from TV’s “Lassie.” Pre-1996, we would have concluded “maybe,” shrugged, and forgotten about the question. But the newfangled-y World Wide Web made the answer obtainable. At 2 a.m., I geaded down the hallways to search the still-frontierish WWW. After around fifteen minutes, I found that the kid was, indeed, Jeff Miller. I also learned that the actor, Tommy Rettig, had a brief film career, became a software guru, grew obese, lived on a boat, and died just months before my websearch. Alanna and I had zero need of any of this information, but that evening’s search put an end to shrugs as acceptable responses to obscure questions. And some of the sadder corners of the late Mr. Miller’s life were there for total strangers like us to peruse at our leisure.

Around the same time, our then-pre-teen son’s teacher asked each student to write an essay about some animal. Rather than “cow” or “horse,” precocious son chose “anoplogaster”—a deep-sea fish almost entirely absent from the 1996-era Web. Searching yielded little information other than the email address of the world’s foremost anoplogaster expert—a marine biologist in Scotland. Our son emailed, and a day later the requested information arrived. The biologist apologized for his 24-hour delay in answering. (He had been diving off Cyprus, he explained.) Immediacy was now expected.

Soon thereafter, wife, son, and I read My Name Is Asher Lev The Chosen, a novel by Chaim Potok. We inconclusively debated whether a particular plot point was realistic or fictional. The Web offered up Potok’s email address, so we wrote to ask the author his thoughts. The next day, Potok sent a cryptic answer. Minor celebrities were now reachable.

Web-surfing led me to a site enabling viewers to manipulate a robot at some Australian university. I was an inept robot pilot and toppled the thing, eliciting an automated warning to be more careful. My fingers could now wreak havoc at the antipode.

My employer lent me a gigantic Gordon Gecko-ish cellphone for a business trip. In a remote stretch of Idaho, the phone rang—my wife simply saying hello. Out-of-touch was obsolete.

In Virginia, a young woman was duped into believing that her car was malfunctioning. In a world of cellphones, she would have called AAA. In 1996, she accepted a ride with the man who told her that her car was broken. Off they rode, and her body was found months later. Shuddering from the story, I purchased a cellphone for my wife.

Lecturing at the Federal Reserve, I asked listeners for home addresses. I entered their answers in Mapquest—then a hot new product—and the screen flashed maps pinpointing their homes. This audience gasped in terror at the loss of privacy and anonymity.

In 2000, I flew to Almaty, Kazakhstan via Amsterdam. In Amsterdam, I spied a sign touting “Internet Cafe”—a new expression to me. Over beer and fries (at 6:00 a.m.!), I emailed my family in Virginia as they slept. Arriving in Almaty, my ATM card successfully summoned Kazakh currency—to my utter amazement. Communications and finance were now immediate and everywhere. The family’s response to my Amsterdam email was waiting at the hotel.

In September 2001, one of my students emailed to say she wouldn’t be in class that evening. Her brother-in-law had been atop the World Trade Center for a business breakfast when the planes hit that morning. She said he fired off a few goodbyes from his BlackBerry and then was heard from no more. I wondered what a BlackBerry was.

In Rocky Mountain National Park, around 2002, my cellphone rang. My wife conveyed a panicky plea by an administrator at my university for some receipts. From 10,000 feet up, I helped her locate, scan, and fax the receipts to my office. I got reimbursed. After that, I was never truly away from the office.

In 1989, television actress Rebecca Schaeffer was murdered in the doorway of her apartment by a deranged fan who had gotten her address from the Department of Motor Vehicles. California quickly pass anti-stalking legislation—but those privacy protections were rendered moot by the internet just a few years later.

In 2003, photographer Kenneth Adelman took an aerial photo of the California coast that included Barbra Streisand’s mansion—one of 12,000 photos posted on Pictopia.com to document coastal erosion. Streisand filed a $50,000,000 lawsuit against Adelman and Pictopia for invasion of privacy. The court dismissed the suit and ordered Streisand to pay Adelman’s $177,000 legal bill. It turns out that before Streisand sued, the photo had only been downloaded six times—including twice by her own attorneys. After the publicity over the lawsuit, the photo was seen millions of times and posted all over the web. This gave rise to an internet axiom that efforts to seek privacy on the web will result in the obliteration of that privacy via massive publicity. Tech CEO Mike Masnick later named this axiom The Streisand Effect.

In 2015, an inspiring Cadillac ad featured Njeri Rionge, a hairdresser who became CEO of an East African internet provider. I tweeted the ad, including her handle. From her place in Kenya, seconds later, she clicked “like.” I clicked “follow.” She clicked “follow.” We texted, costlessly, for the next 30 minutes across 8,000 miles. (I was lying in bed in a darkened room next to my sleeping wife throughout this chat.) Rionge and I discussed how difficult my Africa-to-America communications had been in 1984. She was just a few hundred miles from the Lake Malawi cabins were I had felt so secluded thirty years earlier.

Each of these memories went from unfathomable to commonplace. They ended a world we barely remember. Sometimes, I miss that world.

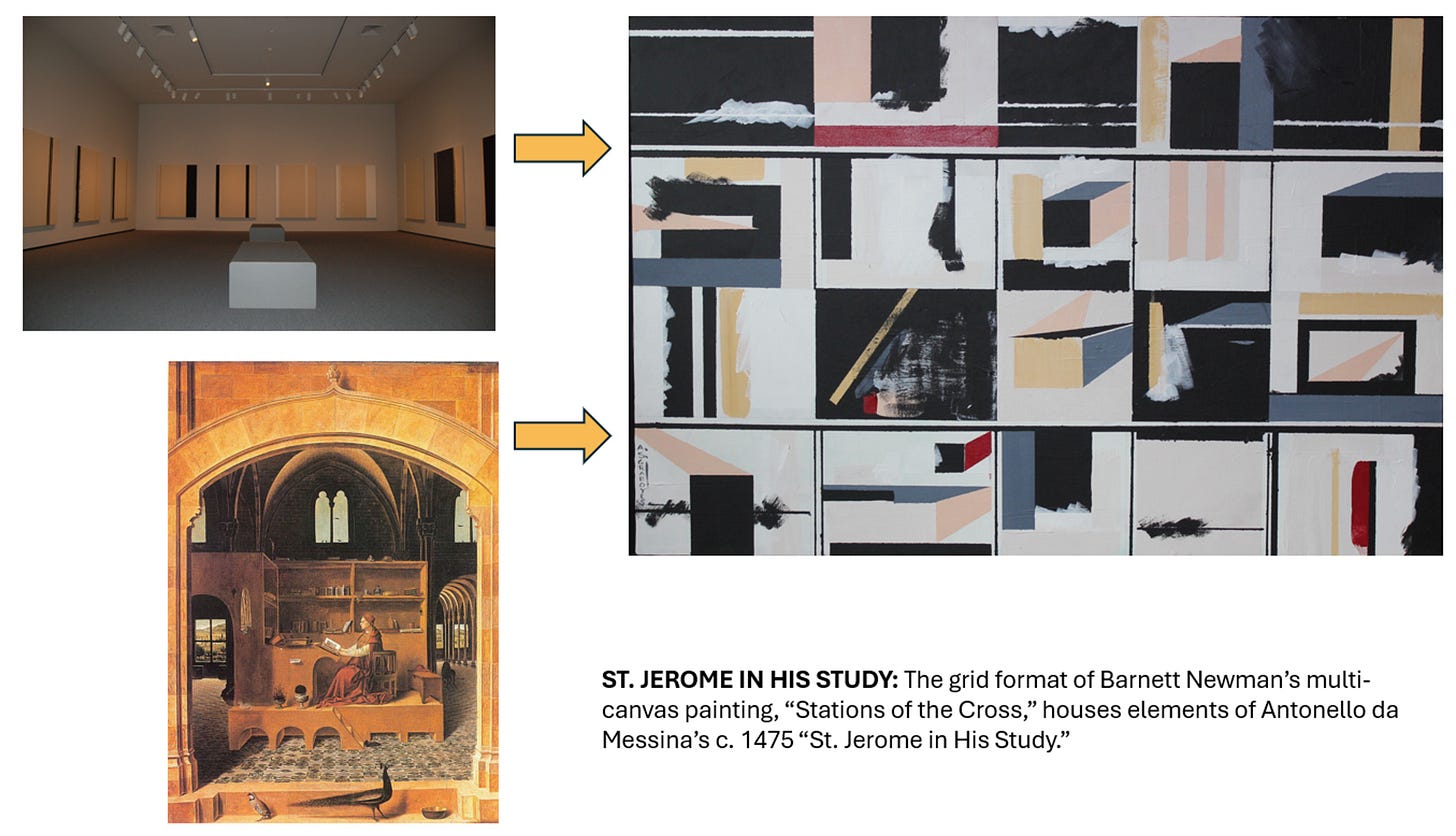

ANOTHER “ST. JEROME IN HIS STUDY”

My wife, Alanna, also did a painting titled “St. Jerome In His Study.” Hers took elements from the Antonello da Messina painting and adapted them to the grid patterns of Barnett Newman’s “Stations of the Cross.”

How I love your essays.

I keep pointing to people how that little silicon chip is changing EVERYTHING. Some Good some Bad, and we're still trying to figure it out.

What amazes me is how so many people are (apparently) Not Amazed.