Life Magazine's 1916 American Nightmare

Life's dystopian warning foreshadowed Philip K. Dick's "The Man in the High Castle"

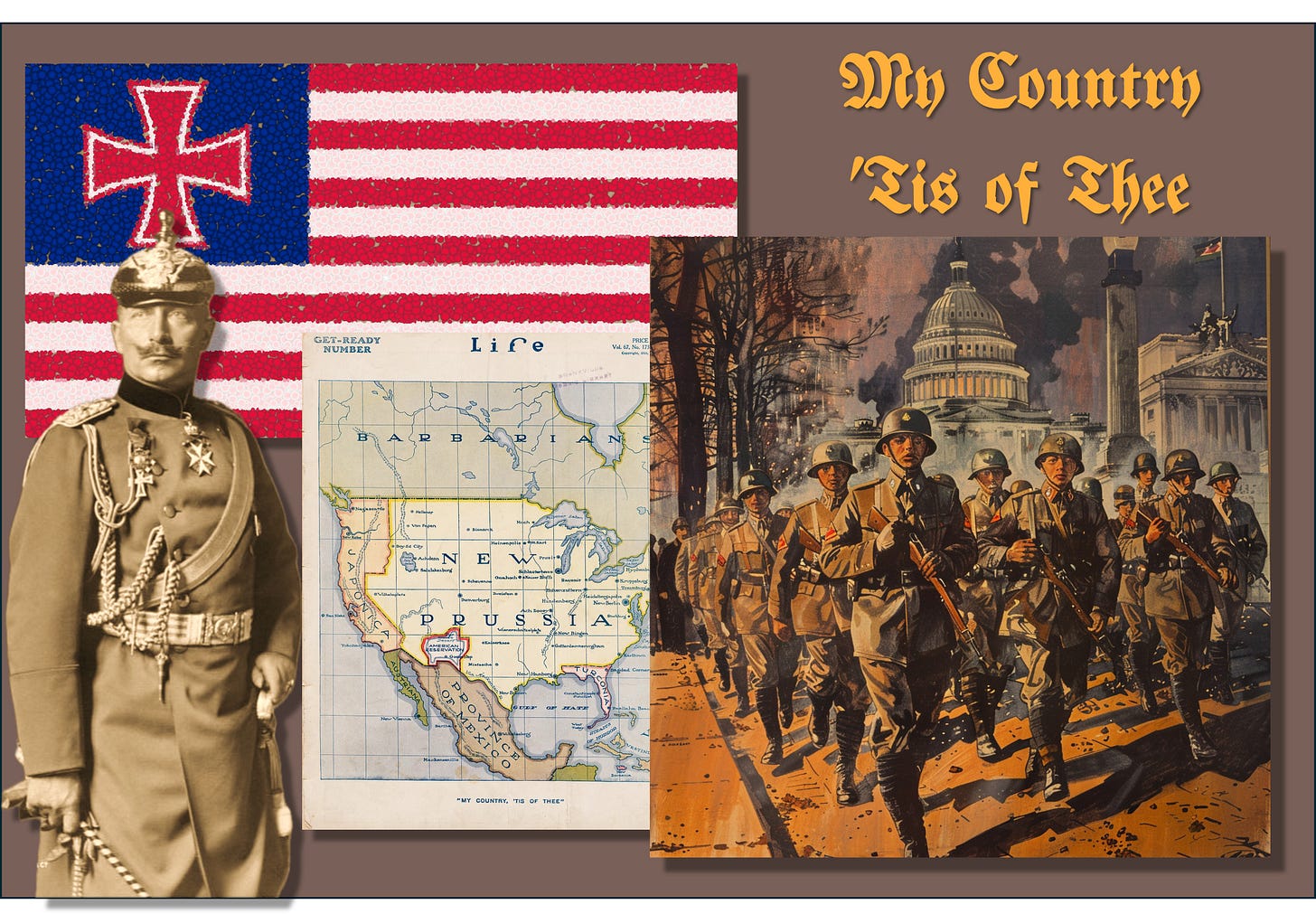

For over a century, a recurring nightmare—America, conquered and dismembered by Germany and Japan—has enthralled and terrified readers of world affairs and fiction alike. Below, a series of maps illustrates this vision, ultimately leading back to a February 1916 Life magazine cover.

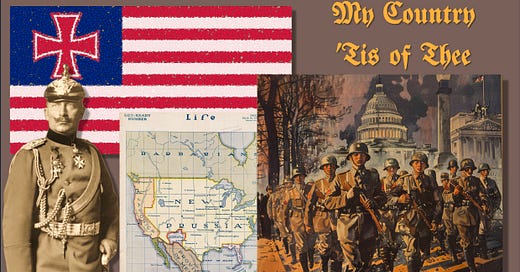

The Man in the High Castle (1962 and 2015-19)

A slight change in the trajectory of a bullet can change history. On February 15, 1933, anarchist Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Franklin D. Roosevelt, injuring four people and killing the mayor of Chicago. The bullets missed Roosevelt, who became president 17 days later.

In Philip K. Dick’s 1962 alternative history novel, The Man in the High Castle, One of Zangara’s bullets kills FDR, ultimately leading to a 1947 victory by the Axis Powers over the Allies. Nazi Germany conquers the United States east of the Rockies, while Japan establishes a vassal state west of the Rockies. American Jews are slaughtered and slavery is reinstituted in America after an 82-year hiatus. The only remnant of the old America is a lawless Neutral Zone between the German and Japanese lands.

From 2015 to 2019, Amazon Prime adapted Dick’s novel into a riveting television series. The opening credits included the above map.

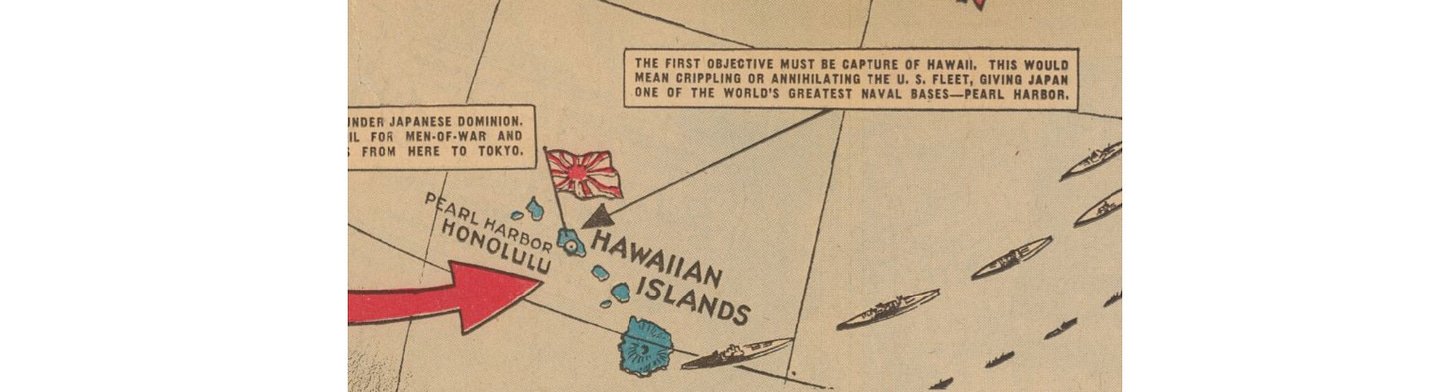

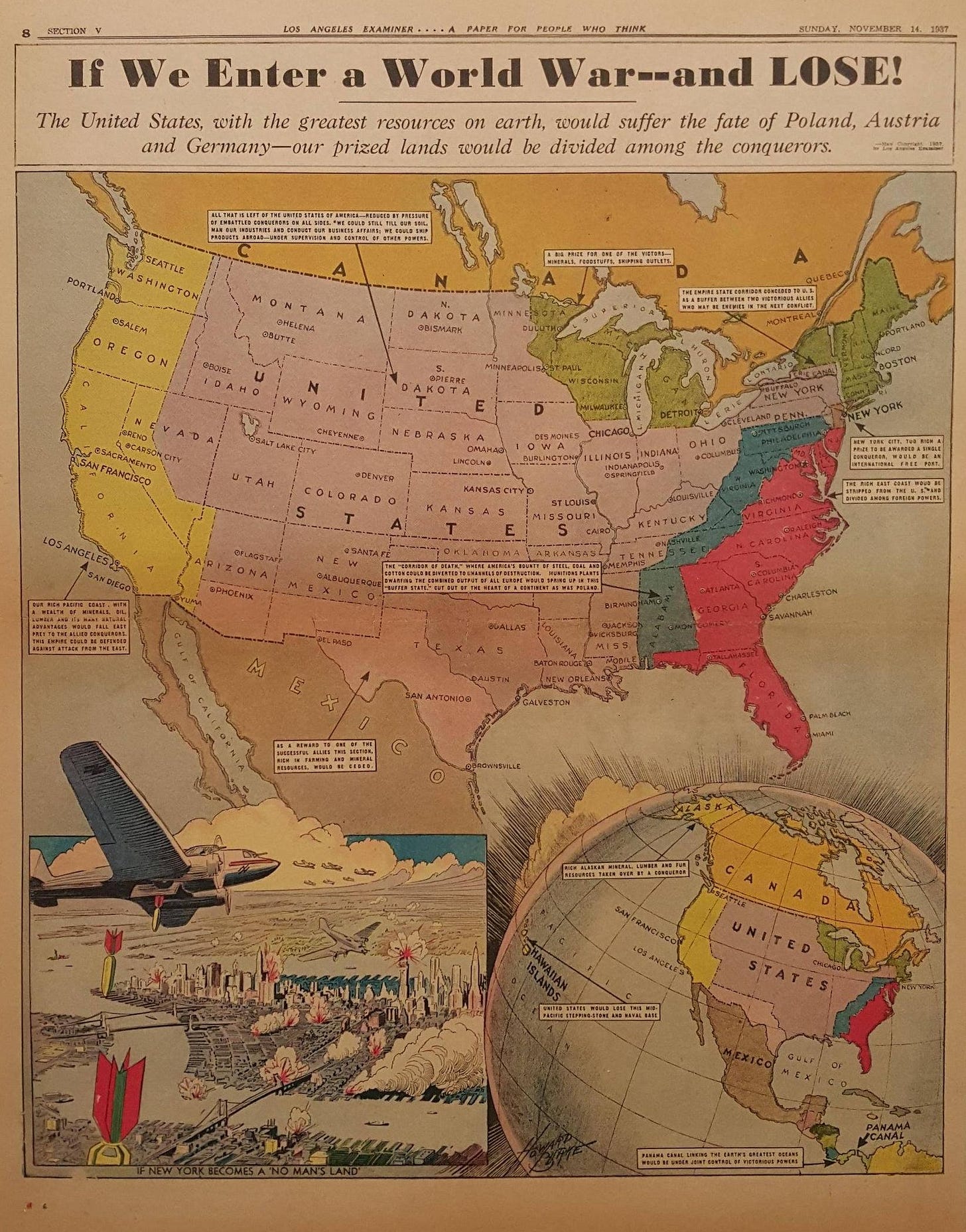

HOWARD BURKE’S L.A. EXAMINER MAP (1947)

On November 14, 1937, two years before World War II began in Europe and four years before America’s entry into the war, William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner (and Chicago Herald and Examiner) published a full-page map by Howard Burke: “If We Enter a World War—and LOSE!” Recalling the aftermath of World War I, the subtitle was:

“The United States, with the greatest resources on Earth, Would suffer the fate of Poland, Austria & Germany—our prized lands would be divided among the conquerors.”

In Burke’s map, the United States is reduced to a large rump state lying mostly east of the Rockies and west of the Appalachians. The remainder of the country is divided into nine coastal states under the control of unspecified foreign countries.

A week earlier (November 7, 1937), Burke produced another map: “How Japan Could Attack U.S.” In some respects, the map is remarkable in its prescience, as can be seen in the small section below. The inscription reads:

“The first objective must be capture of Hawaii. This would mean crippling or annihilating the U.S. Fleet, giving Japan one of the world’s greatest naval bases—Pearl Harbor.”

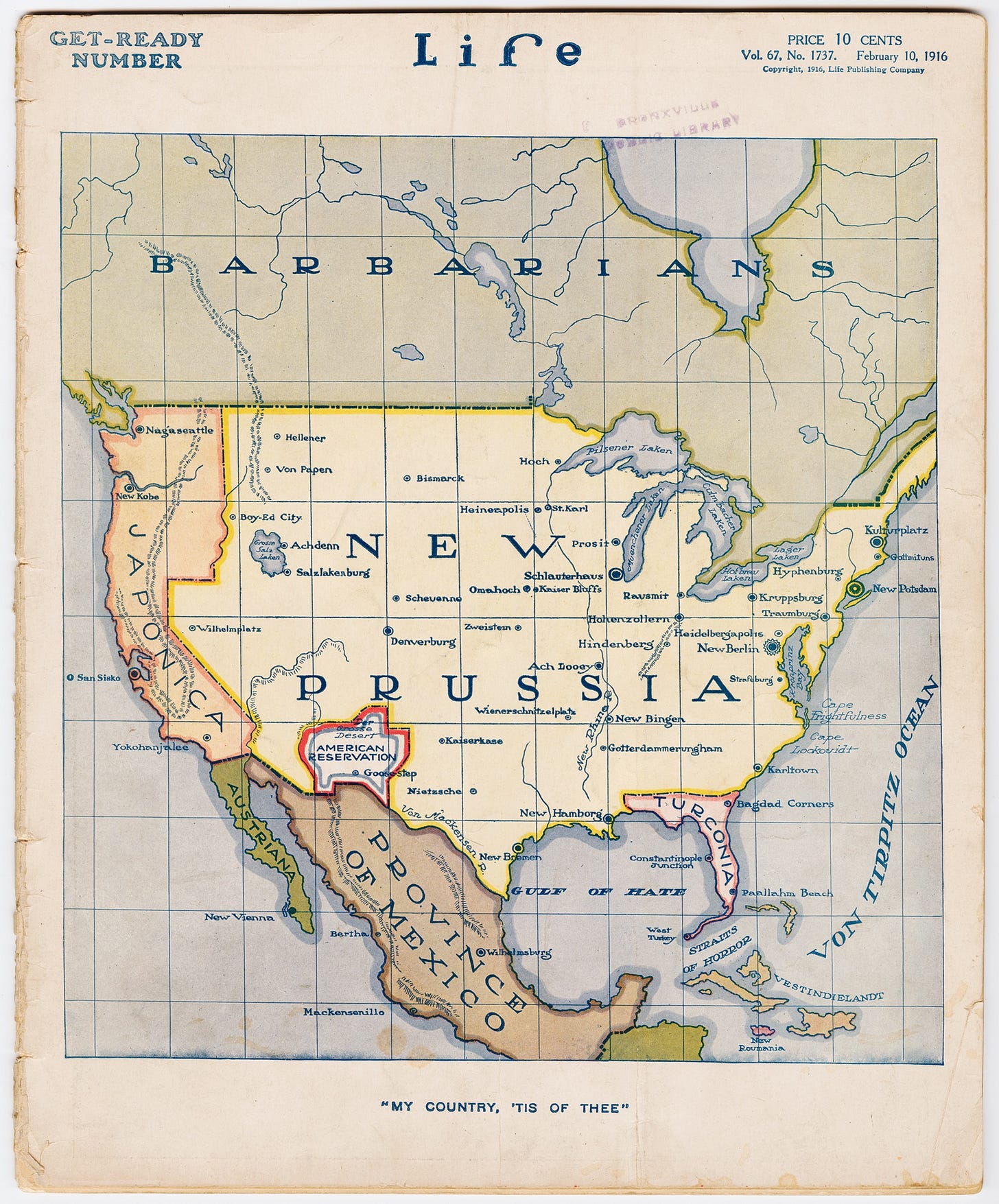

“MY COUNTRY ‘TIS OF THEE” (1916)

The February 10, 1916 cover of Life magazine bears a striking resemblance to the map shown in the television adaptation of The Man in the High Castle. (In Dick’s novel, German America was divided into two entities, North and South.) I have no idea whether Dick had seen the Life cover or the Burke maps or was inspired by them.

The Cornell University Library’s explanatory information regarding this map begins:

“Early in 1916, the U.S. remained neutral in World War I in light of strong isolationist and pro-German sentiment. Life Magazine, on February 10, 1916, weighed in on the other side with a ‘Get-Ready Number’ featuring a dramatic cover map in color … . The map shows the U.S. renamed New Prussia, and American city names replaced with German or Germanized versions. Washington is New Berlin, Chicago is Schlauterhaus, and Boston is Kulturplatz.”

A few observations come to mind:

Life’s map appeared while Woodrow Wilson was seeking re-election on the slogan, “He kept us out of war.”

As in The Man in the High Castle, Life’s dystopian vision showed America largely divided between Germany east of the Rockies (“New Prussia”) and Japan west of the Rockies (“Japonica”).

The remnants of the U.S. are limited to an “American Reservation” straddling portions of what had been New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas.

Here, the enemy is not Nazi Germany, still 17 years in the future, but rather the Imperial Germany of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Virtually every city in New Prussia has a new German name. (For example, Washington, DC is now “New Berlin.”) As far as I can see, the only exception is Bismarck, North Dakota, which remains unchanged, for obvious reasons.

The Great Lakes have been renamed for beers (Pilsener, Culmbacher, Muenchener, Lager, and Hofbrau).

Canada is listed only as “Barbarians,” with no cities listed. Presumably, things really went south up north.

Mexico has lost its sovereignty and is under German sovereignty, with its capital at “Wilhelmsburg.” In the real world some months after Life’s map appeared, Imperial Germany secretly offered Mexico a deal. If America entered the war, then Mexico would ally with Germany, and Germany would help Mexico reconquer its lost territories of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. This proposal came to light via the Zimmerman Telegram, which helped persuade the U.S. to enter the war soon after Wilson’s second inaugural.

Baja is now a possession of Germany’s ally, Austria-Hungary. The peninsula has been renamed “Austriana,” with its capital at “New Vienna.” This is appropriate, given the history of Austria-Hungary’s emperor, Franz Joseph I. In 1864, the French installed his younger brother, Maximilian, as Emperor of Mexico. He was overthrown and executed in 1867. So, Austriana might be sweet revenge for Maximilian’s death.

Florida is now “Turconia”—presumably a possession of the Ottoman Empire. In 1916, before the advent of air conditioning, the sparsely populated Florida would have been a relatively unattractive colonial outpost. Ottoman Turkey was known as “the sick man of Europe,” so it is fitting that they would have received the geographic equivalent of table scraps.

Puerto Rico is now New Roumania. When the map was drawn, Romania was neutral, though the Central Powers had eyes on it. Later in 1916, Romania entered the war on the Allied side, though the Central Powers managed to capture and neutralize Romania for a while.

Most curious is “Japonica,” encompassing California, Oregon, and Washington. During World War I, Japan was officially a member of the Allies and, as such, an enemy of the Central Powers. However, Japan was already exhibiting the strong drive for territorial expansion that led to its role as an Axis Power in World War II. As Japan grabbed portions of China and various Pacific islands, the Allies began distancing themselves. Perhaps “Japonica” reflected this growing unease, or perhaps it simply reflected the American hostility toward Japanese people that culminated in the World War II internment camps.

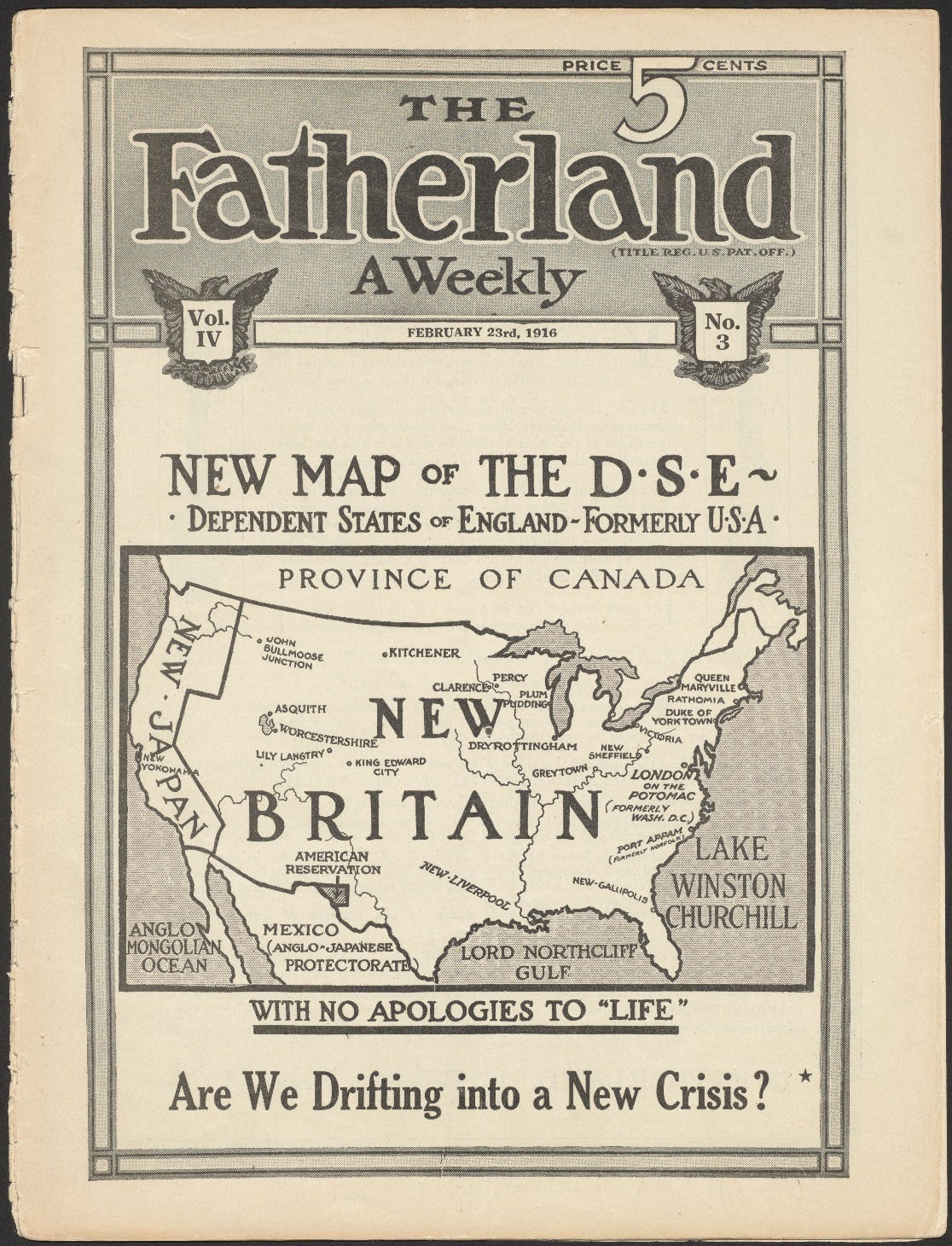

THE DEPENDENT STATES OF ENGLAND (1916)

Finally, Life’s anti-German map elicited a response by The Fatherland—a pro-German American periodical published by poet, writer, and propagandist George Sylvester Viereck, whose magazine called for “Fair Play for Germany and Austria-Hungary.” Blaring “WITH NO APOLOGIES TO ‘LIFE’!”, Viereck offered his own map, with North America conquered not by Germany and Japan, but rather by Great Britain and Japan. Viereck was imprisoned during World War II for his pro-Nazi activities in the U.S. Interestingly, his map renames the Atlantic “Lake Winston Churchill,” demonstrating the esteem in which Churchill was held before his years in the political wilderness between the two wars.

LAGNIAPPE

THEY SHALL NOT GROW OLD (2019)

For a century, most of us have filtered out thoughts on World War I through silent, grainy, comically herky-jerky films. In 2019, director Peter Jackson changed that with his remarkable film, They Shall Not Grow Old. Jackson used 21st century technology to add realistic color, sound, and fluidity of motion to the ancient footage. In 2023, I described Jackson’s achievement at length in, “That the Past Shall Not Grow Old: On the challenge of making history memorable and contemporary.” Here’s a short documentary on Jackson’s WWI masterpiece, followed by the trailer from the film itself.

Thanks for the shout out to “They Shall Not Grow Old.” It’s one of the most remarkable films I’ve ever seen. When I saw it in a theater while it played in selected cities, the film was followed by a feature which explained the extent of authenticity to which Peter Jackson ascribed — even to determining the regional accent that would’ve been spoken by the individual soldiers. Plus the authenticity of the explosions made by various artillery. Truly an amazing accomplishment, as well as a work of love for the history of WWI by Jackson.

Robert, Thanks for a fascinating post. I enjoy reading pre-war geopolitics, and just found a copy of Robert Strausz-Hupe’s “Geopolitics: The Struggle for Space and Power” from 1942. It’s very hard to find. This post reminded me it is waiting for me to dig into.

Cheers.