Two years ago (9/14/2022), I published “Mother at 100,” on the centenary of my mother’s birth. I loved the essay, but the then-brand-new Bastiat’s Window had few readers then, so not many people saw it. Here it is, updated to reflect the passage of two more years.

102 years ago today, September 14, 1922, my mother, Lois Graboyes, was born in Petersburg, Virginia. For me, 1922 sounds a fair ways back, but not ancient history. But the magnitude of that time span becomes clearer when I imagine the world that existed 102 years before her birth.

On September 14, 1820, James Monroe was president—the last of the Founding Fathers to hold that office. In that year, Britain ended centuries of piracy, kdnapping for ransom, and slave-taking by Arab sheikdoms on the Persian Gulf. Britain also ended execution by decapitation on its own soil. Antarctica was identified as a land mass. The Missouri Compromise enabled the admission of Missouri and Maine as slave and free states. Joseph Smith’s First Vision presaged the founding of the Mormon faith. The Venus de Milo was discovered. William Tecumseh Sherman, Susan B. Anthony, Florence Nightingale, Herbert Spencer, Jenny Lind, and Friedrich Engels were born. Benjamin Latrobe, Daniel Boone, and King George III died.

Mom’s birth preceded the Great Depression, World War II, television, rocketry, and the discovery of both Pluto and the neutron. 102 years earlier, the telephone, telegraph, camera, elevator, escalator, automobile, passenger railway, airplane, sewing machine, vacuum cleaner, air conditioner, and typewriter lay years into the future, as did aspirin and Coca-Cola. Our hometown was a hellscape of slavery and would host the final great battle of the Civil War 45 years later.

My field of study, healthcare, may present the starkest contrasts of all. At age 92, Mom had a near-death experience. One evening, she was using her beloved iPad to FaceTime with her grandson, an emergency physician. In the course of the conversation, he detected hints that she might be in the early stages of toxic shock; she was, and rapid response and massive doses of antibiotics saved her life. But at the time of her birth in 1922, efficacious antibiotics were no more available than iPads. Mom’s birth was only a decade past what Harvard medical school professor referred to as “The Great Divide,” when, he said, “for the first time in human history a random patient with a random disease consulting a doctor at random stands a better than 50/50 chance of benefiting from the encounter.” From the 1820s till the 1920s, medicine was largely mired in an era of “therapeutic nihilism,” when doctors often took Hippocrates’s “do no harm” to mean “do nothing.” This utter loss of professional self-confidence came about because modern science was conclusively demonstrating that 1,600 years of leeches, bloodletting, and bodily humor-based therapeutics had done much harm and little good for patients.

In 1922, F. Scott Fitzgerald branded the era “the Jazz Age,” and as a lifelong jazz fan, my mother took took pride in that designation. A century earlier was known as the Era of Good Feelings—the relatively quiet period following the War of 1812. In The Birth of the Modern, historian Paul Johnson argued that everything changed between 1815 and 1830:

“political, economic and demographic changes, all without precedent in their scale and future significance, were accompanied by powerful new currents in music and painting, literature and philosophy, some ennobling and refreshing, some sinister.”

We are as far today from my mother’s birth as her birth was from doctors in powdered wigs treating cancer and respiratory problems with tobacco smoke enemas.

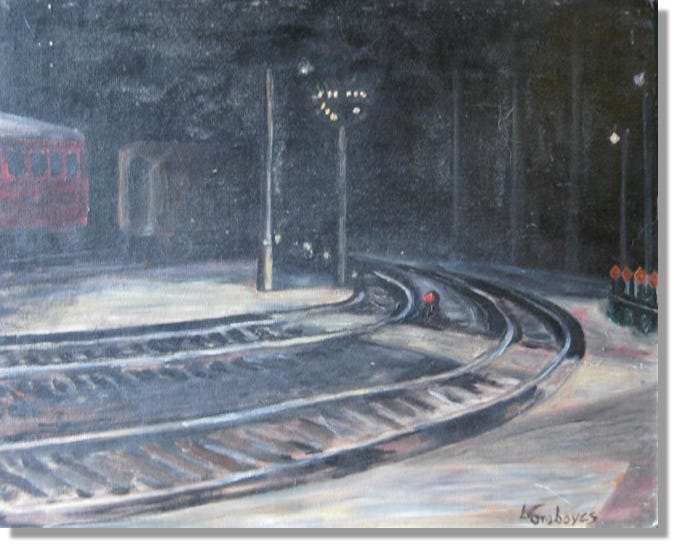

From age 80 to age 91, my mother served as an historical tour guide for the Civil War battlefields and museums of Petersburg, Virginia. As I wrote, one of her cherished experiences occurred in 2011, when she provided historical information to screenwriter Tony Kushner, who was in town working with Steven Spielberg on the filming of Lincoln. Much of Spielberg’s masterpiece was filmed around an old railway station which my mother had painted half a century earlier.

Mom’s service as a Civil War tour guide was more than appropriate. As a young woman, she would have known people who were present at the scenes Spielberg portrayed in his film. The older townsfolk of her youth included former slaveholders and former slaves. Her birth certificate bears the signature (probably rubber-stamped) of Walter Ashby Plecker, Director of Virginia’s Bureau of Vital Statistics and, effectively, the state’s chief eugenicist. A medical doctor, he spent decades accumulating (and sometimes fabricating) genealogies of Virginians to systematically strip African Americans, Native Americans, and others of rights and privileges. Born 10 days before the attack on Fort Sumter, Plecker boasted in 1943 of his racial database on Virginians: “Hitler's genealogical study of the Jews is [probably] not more complete.” (In 2023, I wrote this piece on Plecker.)

When she died in 2016 at 93, Mom was still living independently. When I visited her a month earlier, her legs were a bit wobbly, but her mind was still razor-sharp—the Jazz Age still alive and well in her thoughts. For hours, we discussed art, music, architecture, science, health, food, computers, religion, politics, history, and more. Two weeks or so later, during my next visit, she was drifting in and out of a mental fog, with reality melding with hallucination. She was acutely aware that something was badly amiss. She was confused and could barely sustain a conversation.

Rather than forcing her to talk, I began playing the piano—“Yesterday,” by the Beatles. My parents were not keen on the Beatles in the early days of the group’s fame, but they both immediately loved “Yesterday.” I thought that memory might comfort her. She asked, “Is that a Gershwin song?” I gently reminded her that it was by the Beatles, not by the Gershwins, and she said, in a whisper, “Of course it is.” She never liked making errors of any kind, and she had an encyclopedic knowledge of George and Ira Gershwin, whom she had revered for 80+ years. When she made that unimaginable error, it instantly struck me that her days were near their end, and I think she had the same thought. A talented amateur pianist, the day before her 92nd birthday, she had given a performance before a sizable audience. This brief snippet from that day shows her playing the Gershwins’ “The Man I Love” (1924).

To those children born today, September 14, 2024, may your lives be as long and well-lived as my mother’s. And here’s hoping that on September 14, 2126, your progeny are looking back with wonder on the eons that have passed since your birth and marvel at the innovations that time and ingenuity have wrought in the century since you took your first breath.

1922: LOIS AND TUT

My mother, Lois, memorialized in the essay above, was born on September 14, 1922. Seven weeks later, on November 4, Howard Carter and his team uncovered the entrance staircase to the tomb of Tutankhamen. Below are two depictions of the Boy Pharaoh—one from the tomb and the other of later vintage.

Your memory of your Mom and her love of music has a similarity to my last memory of my Dad. He was 101 years old, and my sister had driven him to our brother's home to celebrate his birthday. I attended by video call.

A year or so before, I convinced my publisher to publish a chapbook of his poetry. He was a renaissance man; scientists, Boy Scout Commissioner, school board member, father, and quietly wrote poetry, which he had sent to me several years before this.

I called my sister and she took her phone over, letting my Dad know that I was calling. The look on his face resembled that of a lost child, not sure of his surroundings or what was happening in the room.

My sister told him I'd sent a gift, opened it and said, "Look Dad, it's a book of your poetry Emily got published." He barely reacted. Then she opened the book to a random page and started reading one of his poems. I saw his lips moving as he quietly recited it from memory. The same happened with two others she read, that he recited along with her without even looking directly at the book.

It was a reminder of how something of us can remain in our consciousness even when we appear to be "out of it" in the eyes of others. And I was grateful my publisher allowed me to create this gift, something that sits on the shelf of many of his relatives and their children.

What a loving tribute !