Real-World Trade-Deficit Math-Magic

Long ago, I helped bankers lending billions of dollars in Africa by teaching them a few equations related to trade deficits. Those equations are critical to understanding today's tariff controversies.

In the 1980s, I was the economics officer for Chase Manhattan Bank’s lending operations in Sub-Saharan Africa, where our offices lent billions of dollars. My job was to examine the economic data and policies of around two dozen countries, place them in the context of world markets, and offer the bankers advice on whether we should increase or decrease lending in each country. Most countries in the region were destroying their economies by imposing tariffs, quotas, exchange controls, capital controls, and draconian regulations. Nigeria, for example, used tariffs to encourage industrialization; the result was to turn a once-mighty exporter of food into a half-starved basket case alternating between importing food and too-poor-to-import food.

Chase’s lending and credit officers were the most brilliant, accomplished individuals I ever worked with. I could never hope to compete with them on the details of the countries—business environments, growth opportunities, borrower reputations, product details. I had only one advantage over them—they knew the trees, but I understood the forest. They could tell me which borrowers were best, but I could suggest when national policies and international conditions made even the best borrowers unacceptably risky.

Early in those years, I argued that for them to understand the big picture in a given country, they needed to understand four simple, but sublime, equations and what that algebra told us about trade deficits, government budget deficits, personal consumption, and private investment. In 2025, to understand the firestorm over President Trump’s tariffs, it’s necessary to comprehend those same four equations. A little high-school algebra will give you a better grasp than almost any politician or newscaster you’ll encounter.

My previous column (“Tired of Winning, Apparently”) roundly criticized tariffs in general and President Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs in particular. If you haven’t read it and don’t know my work, this isn’t a case of Trump Derangement Syndrome. I’m a political nomad with no partisan allegiance, but I’m favorably inclined toward some of this president’s actions on DEI, antisemitism, energy, deregulation, border control, Hamas, Houthis, and more. In particular, snatching $400 million in grants away from my alma mater, Columbia University, really gets my endorphins flowing. In the 1800s, the current Columbia campus was the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum—a mental institution for rich people. Trump ought to make restoration of those grants contingent upon Columbia changing its name back to that of its previous owner.

However, I consider President Trump’s tariff policies to be dangerous for the country, for the world, and for his own agenda, party, and legacy. To explain why, let’s walk through the same lessons I shared long ago with those bankers.

“IDENTITY” VERSUS “EQUALITY”

The key to understanding the arguments below is to understand that all the equations are IDENTITIES (statements that are true by definition), and not simply EQUALITIES (hypotheticals that may or may not be true).

An EQUALITY uses math to represent a theory, hypothesis, conjecture, or guess. For example, some economist might theorize that the price level is always equal to the amount of money in circulation times some fixed number k. If true, a 10% increase in the money supply leads to a 10% increase in prices. But data and further theorizing may show this equality, this conjecture, to be false. Here’s what this equality looks like:

(PRICE LEVEL) = k×(MONEY SUPPLY)

An IDENTITY uses math to represent relationships that are true by definition. Identities use a special equal sign that has three lines, rather than two, indicating that this equation is not merely a hypothetical conjecture. Here are two examples:

(MILES PER HOUR) ≡ (MILES TRAVELED)/(HOURS OF TRAVEL)

The truth of this statement is self-evident and not debatable unless you are (1) into relativistic physics, (2) on psychotropic drugs, or (3) obnoxious. Now, consider a second identity:

(PROFITS) ≡ (REVENUES) - (COSTS)

This is not a theory about how companies operate. It’s just an accounting statement that explains how we define profits. There may be different ways to measure revenues and costs, but once you choose a method for measuring each, this equation is automatically true.

ALL of the international trade discussion below consist of identities (truths), not equalities (hypotheses).

[1] Y ≡ C+S+T

income ≡ consumption + saving + taxation

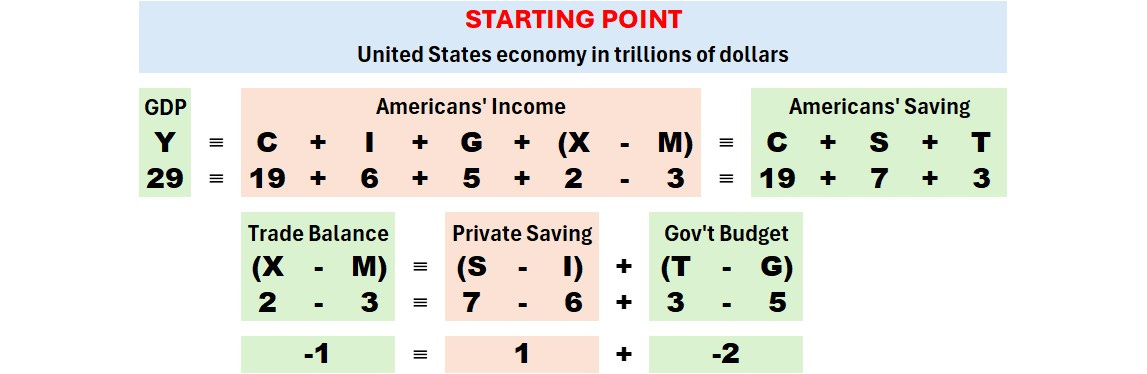

In 2024, Americans earned around $29 trillion ($29t) dollars in income, and every one of those dollars went to some place. We can divide those places into three categories: (1) They spent some on consumption goods and services. (2) They saved some for the future. (3) They paid some to the government in taxes (which might be also be called fees, surcharges, levies, tolls, assessments, duties, or tariffs). Those three categories of spending cover every single dollar earned.

[2] Y ≡ C+I+G+X-M

income ≡ consumption + investment + government + exports - imports

For every dollar represented in equation [1], someone on the other side of the balance sheet received that dollar as income. Some sold goods and services to consumers. Some sold stocks, bonds, capital equipment, land, and other assets to investors. Some (including public sector employees) provided goods and services to the government. Some sold export goods and services to foreigners. And to make [1] and [2] equal to one another, we deduct those portions of consumption, investment, and government purchased from foreigners; we call that combined portion “imports” and deduct M from C+I+G+X.

[3] Y ≡ C+I+G+X-M ≡ C+S+T

income ≡ consumption + investment + government + exports - imports ≡ consumption + saving + taxation

Now, the identities in [1] and [2] both equal national income (Y). So, the right-hand sides of both equations also equal one another. Every dollar of American spending reflects a dollar of American income.

[4] (X-M) ≡ (S-I)+(T-G)

(trade balance) ≡ (private saving balance) + (government budget balance)

Here’s the heaviest lift from your high school algebra. Subtract C+I+G from both sides of [3], and group the remaining variables within three sets of parentheses. (X-M) is the trade balance (goods and services). (S-I) is net private saving. (T-G) is the government budget deficit. For each pair, positive means a surplus and negative means a deficit.

MERCANTILISM AND REALITY MADE E-Z

Mercantilism has much in common with Humorism. From antiquity till the early 1800s, Western philosophers swore by Humorism, which held that disease was caused by an imbalance of bodily humors; doctors treated patients by draining their blood, using lancets and leeches. From antiquity till the early 1800s, Western philosophers swore by Mercantilism, which held that economic distress was caused by an imbalance of trade; politicians treated economies by tariffs and other impediments to competition. Humorism was debunked by scientific theory by around 1820–validated by 200 subsequent years of data. Mercantilism was debunked by economic theory by around 1820–validated by 200 subsequent years of data. Doctors abandoned bloodletting by the mid-1800s. Politicians are slower learners than doctors. President Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs are unusually sweeping, but differ only in magnitude, not substance, from tariffs imposed or retained by many presidents, including Nixon, Carter, Reagan, GHW Bush, Clinton, GW Bush, and Biden—and advocated by politicians like Richard Gephardt, Josh Hawley, Nancy Pelosi, Elizabeth Warren, Marco Rubio, Bernie Sanders, Tom Cotton, Sherrod Brown, and Chuck Grassley.

Perhaps it’s easier to think about all this with numbers rather than with symbolic letters. Table 1 turns identities [3] and [4] into numbers, representing trillions of dollars. These are fairly close to the actual U.S. data for 2024. Identical letters always represent identical numbers.

ECONOMIC CLOCKWORK

Table 1 represents the first lesson I taught the international bankers: that the trade balance, net private saving, and the government budget are as rigidly linked as the gears of a clock. Change one and you change one or both of the others in highly predictable ways. Increase the government’s budget deficit from $2t to $3t, and that extra trillion has to come from one of two options:

Increase private saving from by saving more and/or investing less; or

Obtain funding from foreigners via loans, bond purchases, or equity investments.

Both methods will increase the trade deficit by an identical amount. (You could also finance the budget deficit by a combination of private saving and foreign investment.)

A key insight here is that America cannot increase its inflow of foreign investment money AND reduce its trade deficit simultaneously. Aspiring to do both at the same time is logically equivalent to saying, “I want to drive from Santa Fe to Las Cruces half as fast as usual but get there twice as quickly.” It was valuable for Chase’s bankers to understand this Iron Law, and someone would do the current president a favor by convincing him of the same. (Good luck!) As some economist once said, “Even a small child knows that ‘both!’ is not an acceptable answer to the question, ‘Which one?’”

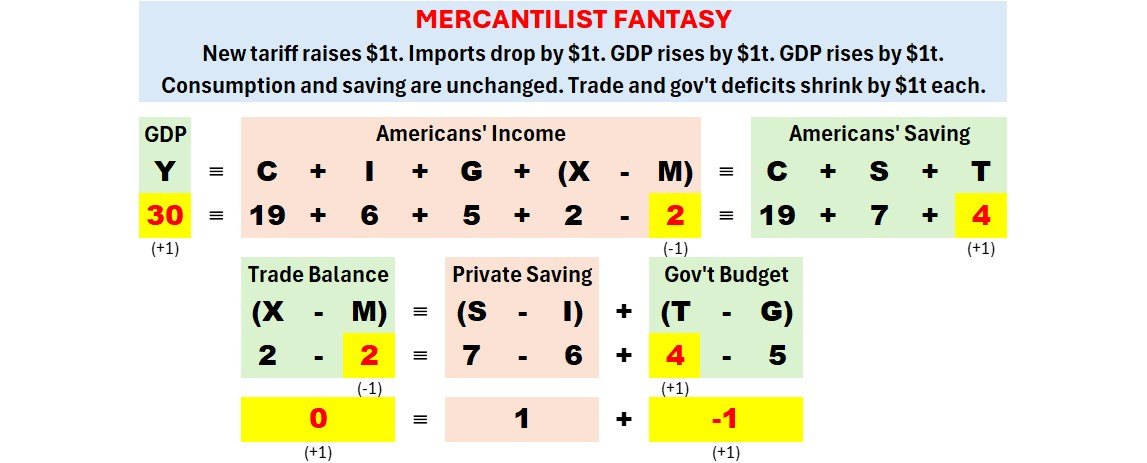

HOW POLITICIANS THINK TARIFFS WORK

In Mencken’s famous words, “There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.” Table 2 uses hypothetical numbers to explore the common-sense and dead-wrong Mercantilist Fantasy that prevailed in the Middle Ages, in 75 years of Democratic Party events with labor unions, and in President Trump’s “Liberation Day” announcement. The government imposes a tariff that raises $1 trillion. Compared with Table 1, imports drop by $1t—as do the trade deficit and government budget deficit. The American economy grows by $1t.

Table 2 does not violate any of the identities in equations [3] and [4], so the Mercantilist Fantasy—tariffs leading to a reduced trade deficit and economic growth is not impossible; it is merely wildly implausible and limited to rare or imaginary conditions. Similarly, bloodletting—the essence of Humorism—is still a valid medical practice, but only in a few, extremely rare circumstances. (It has been rebranded as “therapeutic phlebotomy” and is used for conditions like hereditary hemochromatosis, porphyria cutanea tarda and polycythemia vera.) The conditions where tariffs have beneficial economy-wide effects are similarly rare and arcane, and tariffs are far clumsier instruments than the precision tools used by phlebotomists.

When one digs deeper into the identities and equalities of an economy, the case for tariffs generally falls apart. We can get an idea how this happens by comparing Y=C+S+T from Tables 1 and 2. In Table 1, Y=29, C=19, S=7, T=4. In Table 2, the tariff increases T by $1t and GDP rises by the same amount. This requires a quite bizarre set of circumstances, best illustrated by bringing it down to the individual level. Imagine that 29=19+7+3 and 30=19+7+4 represent Joe Smith’s income in thousands of dollars, rather than America’s collective income in trillions of dollars. Joe earns $29,000 per year. A new tariff raises Joe’s tax burden by $1,000 per year. Faced with a large new tax/tariff payment, Joe decides not to cut either his consumer purchases or his saving, and somehow, out of the blue, a $1,000 manna-from-heaven raise appears on his paycheck to facilitate his decision. Now assume this same story plays out simultaneously for all 325 million Americans—and you have the Mercantilist case for tariffs.

Among other things, this story implies a truly curious assumption. If it is true, then American businesses always had the power to enrich themselves, enrich American consumers, and grow the U.S. economy by simply altering their pricing to underbid China or whomever. Somehow, though, these businesses were just not as smart as the politicians in Washington who imposed tariffs and forced those businesses to earn higher profits. Mercantilism also assumes these politicians have the oversized brains necessary to find just the right tariffs for each country and each product. (Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, and the Tooth Fairy offer more plausible stories.)

Again, such a scenario is technically possible, if you lay down layer after layer of implausible assumptions. In my banking days, practically all the presidents in Sub-Saharan Africa had faith in such stories and destroyed their nations’ economies, one-by-one. In Argentina, Juan Perón had faith in this story and destroyed his country’s economy. In 1930, Republicans led by Reed Smoot and Willis Hawley had faith in this story and helped deepen and prolong the Great Depression. Post-WWII, countless Democrats had faith in this story—encouraged by their labor-union allies. And in 2025, the Trump White House has faith in this story.

Memo to President Trump: Voters in 1932 dumped both Smoot and Hawley into the electoral dumpster when they saw the damage their 1930 tariffs had done to the economy. A Democrat defeated Smoot, but Hawley got the boot from fellow Republicans. So far as I can tell, neither Smoot nor Hawley has any significant memorial—even in their own hometowns. Voters do not take kindly to politicians who crater the economy.

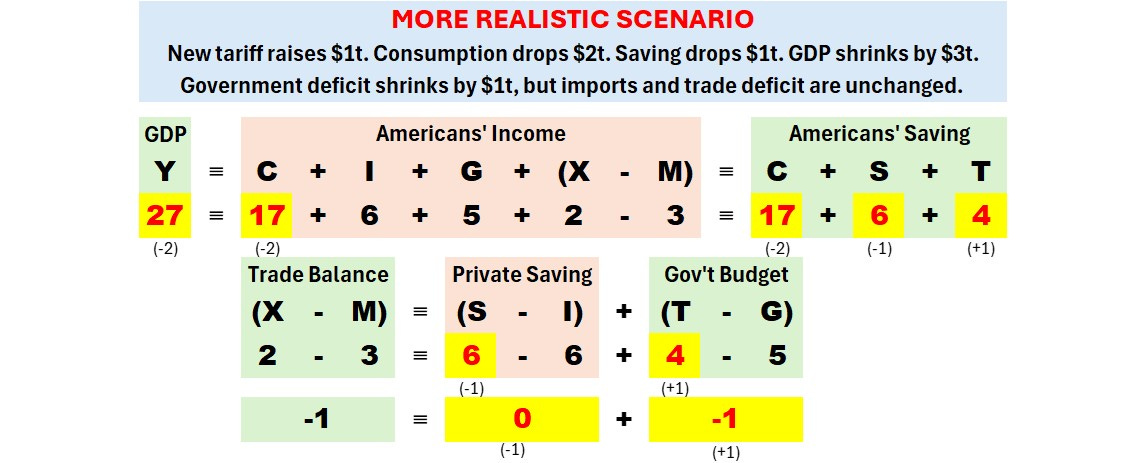

HOW TARIFFS ACTUALLY WORK

Finally, let’s look quickly at what actually transpires when politicians engage their Mercantilist Fantasies (Table 3). Starting again from Table 1, the president once again implements a tariff that increases government revenues by $1t (so T=$4t). While certain producers (say, steel mills and automakers) benefit from the tariff in the short-run, the secondary effects damage the rest of the American economy. Higher steel costs reduce construction; construction workers get laid off; they buyer fewer clothes, houses, and restaurant meals. Auto tariffs reduce auto purchases; dealerships layoff service people and sales personnel get fewer commissions; those workers take fewer vacations and cut down on their purchases of consumer electronics. Etc. Etc. Ultimately, the blowback may even make steel mills and automakers worse off.

In Table 3, the U.S. economy shrinks by $2 trillion. Collectively, Americans save $1t less and consume $2t less. The government’s budget deficit does shrink by $1t as tariff revenues roll in. But—note this—there is no change in the trade deficit. Foreigners still invest $1t in capital in the U.S. (which covers the government’s budget deficit—offset by the same $1t trade deficit as before. Americans are likely buying fewer autos and less steel from abroad. Perhaps they buy less of everything from China. But they find other countries to buy from and other products to buy.

By the way … when China imposes tariffs on U.S. goods, Table 3 also shows the damage they’re doing to the Chinese economy. Their tariffs aren’t any smarter than our tariffs.

Examine the span of recorded history. Try finding an example where the imposition of a tariff enriched some country. If you do, see whether the author also insists that the Apollo moon landings were filmed in the Nevada desert.

The main error that is made here is that Trump is using the tariff issue as a purely Mercantilist way. He is also using it as a geopolitical level. For many years the USA has imported goods from around the world with low or zero tariffs while most other countries are using tariffs and other methods to limit USA imports into their own countries. I believe that Trump's goal is to force these countries to remove their tariff barriers which is why he is using reciprocity with respect to the tariffs. There are also national security concerns with the di-industrialization that has been going on. You do not really want to be in a position in which international supply chain disruptions will leave you with a collapsing economy and society.

Here's a simplistic example to illustrate it what is missing in this analysis.

We used to make our own military hardware worth $1t, but over time we let Buttfukistan supply it for us. Given Graboyes' identities, holding private investment and government deficits even, that would mean the following:

1. We would stop making military hardware.

2. Buttfukistan would sell us $1t in military hardware.

3. With that money, they would buy $1t of our farmland and breweries.

4. When war comes, the stop selling us missiles and they have control of our food beer supply.

5. The "balance" is maintained in terms of cahsflows.

6. We lose the war.

Any economist would tell you that 1-5 is not an economic problem at all. But, they might have to write that analysis in Buttfukistanese.

--