If you find this essay and the accompanying poem/song meaningful, please pass it along to anyone who might share your appreciation. And please consider either a free or paid subscription to Bastiat’s Window and to my YouTube channel.

In 1673, the English poet John Milton published his sonnet, “When I Consider How My Light is Spent,” whose final line is the immortal, “They also serve who only stand and wait.” The poem, also known as “On His Blindness,” was likely written decades earlier, when Milton when pondering his approaching blindness. His words suggest that, even shorn of the ability to work, there would still be a meaningful place in God’s Universe for Milton.

In the centuries since, Milton’s words have been reinterpreted in various ways, and they have multiple meanings with respect to the events of September 11, 2001. In 1943, a veterinary charity in the United Kingdom created the PDSA Dickin Medal to honor the service animals of World War II. As shown below, it is inscribed, “We also serve.” In the months following 9/11, the world watched service dogs digging through the rubble in search of human remains. At one point, rescue personnel were criticized after videos emerged of them playing Frisbee with the dogs atop the deathly mountain of steel, glass, bones, and flesh. Rescue and recovery personnel patiently explained that the work was grueling and traumatizing for the dogs, as well as for the people involved in the operation. Frisbee games were an essential part of staving off exhaustion and emotional collapse for both the service animals and their minders.

But in the popular imagination, Milton’s words probably apply most often to the spouses and families of military personnel and first responders. For example, with one slight variation (“stay” in lieu of “stand”), the passage serves as the motto of the Navy Wives Clubs of America. Milton’s words are also applied to firefighters, police, rescue squads, and others whose families endure waiting and loss.

It was this familial devotion that inspired me in 2011 to compose a poem titled “Laurelyn” as a small tribute to the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) and their families. I set the words to music, with the subtitle “Ballad for the FDNY.” The 9/11 songs I had heard in 2011 were focused on anger, vengeance, defiance, patriotism, and grief. My interest was in honoring destiny, tradition, love, courage, and stoicism. Though the words focus on the wife of a firefighter, I also had in mind the husbands and children and parents and siblings of firefighters, police, and other first responders. (You’ll find a recording and the lyrics at the bottom of this article. I recommend listening with headphones, if you can.)

I decided to publish this piece a week early, hoping that some readers might have a few days in which to pass it along to friends and family who might find it meaningful when September 11 rolls around next week.

From 1983 to 1988, I worked on the 28th floor of 1 Chase Manhattan Plaza—a five-minute walk from the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers. The end of my department’s corridor was a solid wall of glass, looking straight out onto the glistening towers. Sometimes, I would find myself staring out of the window, always with a sense of disbelief about the sheer size of those great monoliths. They somehow made our own 60-story tower feel minuscule. The magnitude and abstract geometry of the buildings robbed one of any sense of scale or perspective. Having lived in New York City since 1980, there was a little corner of my mind that always recalled that on February 20, 1981, Aerolinas Argentina Flight 342 nearly collided with Tower One. Occasionally, while looking out of our window, I would shudder at the thought of how such a collision would have looked from that vantage point.

In 1988, my wife and son and I, weary of the bustle of New York, moved to Richmond, Virginia, not far from my hometown. In Richmond, as in New York, the morning of Tuesday, September 11, 2001 was uncommonly clear and beautiful. While heading to work at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, an announcer interrupted the music on my radio to say that one of the Twin Towers had been struck by an airplane at 8:46 a.m. My thoughts flashed to our window and that 1981 near-miss. Around 15 minutes later, while nearing my office, the announcer said the second tower had been struck at 9:03. Thoughts of Aerolinas Argentina dissipated, as it was obvious that this was no accident.

The Richmond Fed was an especially eerie place to spend that morning. After a third plane struck the Pentagon, rumors spread among the employees that our building might also be a primary or secondary target. As a later press account said:

Soon after 9/11, the Federal Reserve Bank Building in Richmond emerged in media reports as a potential terrorist target. The concern seemed founded. After all, the aluminum-clad, downtown office tower is home to one of only 12 such banks in the country. The 26-story building also happened to have been designed by the same renowned architect who helped design the World Trade Center, Minoru Yamasaki.

In fact, our building looked very much like the Twin Towers—with one tower rather than two, and 26 floors instead of 110. Somewhere mid-morning, most of us were ordered to leave the building and head home. I was extraordinarily grateful to be far from Lower Manhattan—a place that was jammed and chaotic on the best of days. I was also grateful that I had not chosen to attend that year’s meeting of the National Association for Business Economics (NABE), which was held at the Marriott World Trade Center—also destroyed in the attack. 40 people died at the hotel, though so far as I know, no one from the NABE meeting, including families, was lost. I’m still hesitant to bring that day up with friends who were there, as some of them still seem uneasy about the memory.

Funerals proceeded for months as the debris was cleared. Over and over again, Americans were reminded of the service and sacrifice of the first responders and, in particular, of the firefighters. But beyond that, to me, their families’ strength, courage, and dignity seemed superhuman. Time and again, we heard that firefighting was a multi-generational tradition in many of these families.

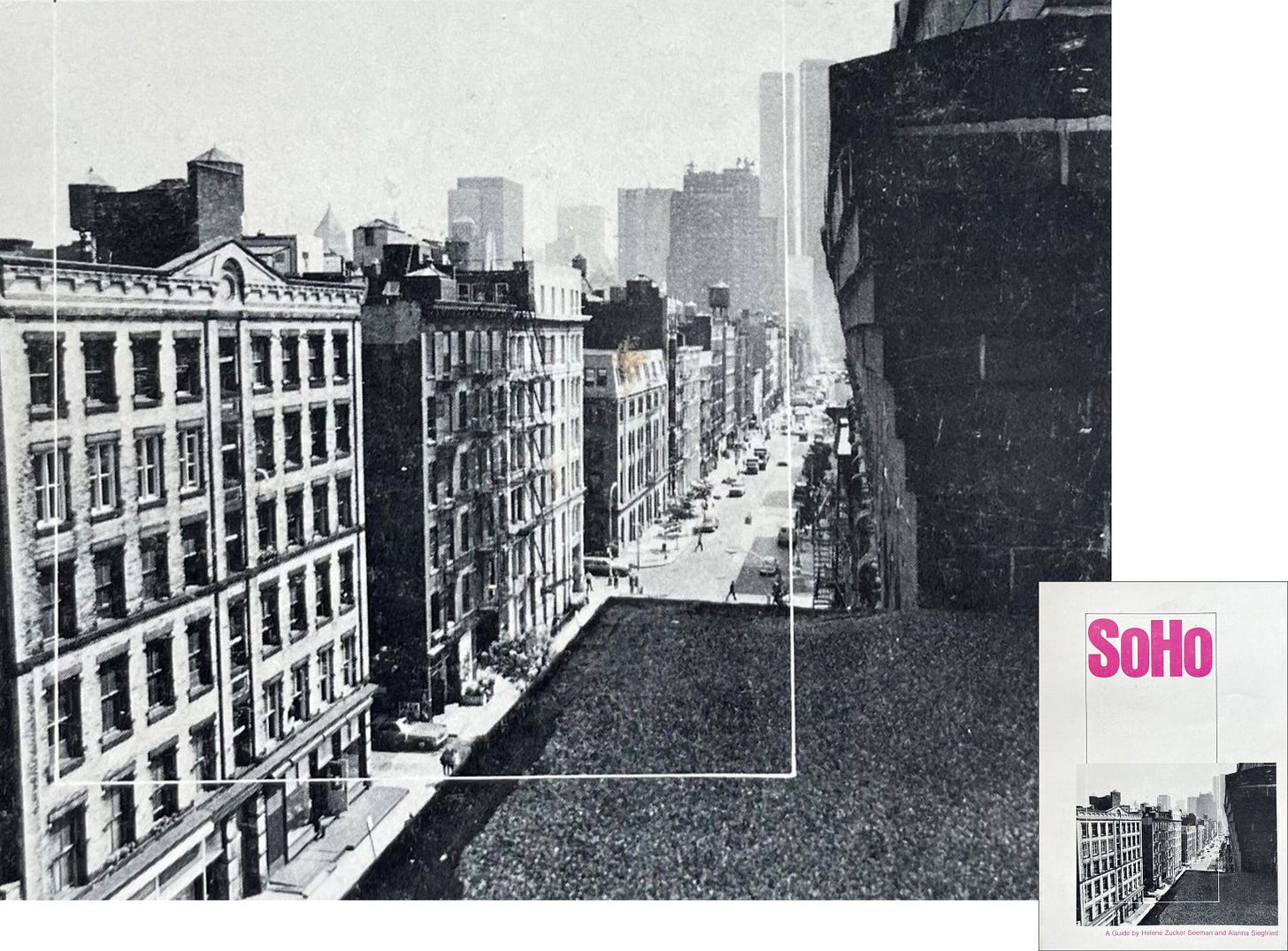

A week ago, my wife, Alanna, and I posted an article (“SoHo + 45”) on the book she co-authored in 1978 on the history and sights of New York’s SoHo Arts District. In conducting her research, she found that many of the great cast iron façades in SoHo originally covered up wooden structures which readily caught fire. As firefighter injuries and deaths mounted, the area earned the name “Hell’s Hundred Acres.” For the cover of her book, Alanna leaned far over the edge of a rooftop to take a photo of those cast iron buildings and the newly built Twin Towers looming in the background. When I see that photo (shown above), I wonder how many firefighters lost on 9/11 had great-great-grandfathers who died fighting the fires of 19th century SoHo.

Firefighters have a tradition of Celtic imagery, especially in New York, so the melody to my song is written in the plaintive Dorian mode common to the British Isles. The Dorian scale conveys melancholy with a hint of optimism—appropriate, I thought, for the subject matter. The performance that follows below has the song scored for a brass military-style band. I also imagine it sung in the manner of a Celtic or country band. (When reading the poem/lyrics, it’s important to know beforehand that “New York’s Bravest” is the official motto of the FDNY.)

Below, you’ll find a recording of and the lyrics to “Laurelyn (Ballad of the FDNY)” which, again, I composed in 2011.

“Laurelyn (Ballad for the FDNY)”

Composed and performed by Robert F. Graboyes © 2011

He was bound for New York’s Bravest, before he had a name.

His father fought the dragon, and he would do the same.

Delivered from his mother into smoke and ash and Hell,

To grasp the hand of God when night is shattered by the bell.

But braver than the Bravest is the one whose life he shares,

Who sends her lover off each day to scale the fiery stairs.

In Laurelyn, he found his love, and found his courage, too,

From deep within her spine of iron and eyes of steely blue.

“Oh, Laurelyn, my Laurelyn, the sirens call for me.

They beg for me to leave you for a caller’s anguished plea.

I should be home by suppertime, but if I fail to show,

Save your tears for those who called me, for you’ll know I chose to go.”

September skies were streaked with tails of black and tongues of red.

And children turned to orphans, midst the ashes of the dead.

Across the boroughs, engines raged and raced past every door.

Below the silver towers, New York’s Bravest massed for war.

“Oh, Laurelyn, sweet Laurelyn, the sirens wail for me.

They summon me to leave you for a caller’s anguished plea.

I should be home by suppertime, but if I fail to show,

Save your tears for those who called me, for you’ll know I chose to go.”

As thousands struggled down, the Bravest lumbered toward the sky.

They vowed to meet the dragons there, and face them eye to eye.

They never reached their quest that day, for soon the towers fell.

So they said their silent prayers, and bid their loves farewell.

* * * * *

The pipes and drums of cold November droned “Amazing Grace.”

Laurelyn had a flag in hand and one tear on her face.

She heard him whisper softly, “Please give the boy my name,

And give him half your courage – just enough to face the flame.”

“Oh, Laurelyn, brave Laurelyn, please love the boy for me,

But let him leave your side to heed an anguished caller’s plea.

He should be home by suppertime, but if he fails to show,

Save your tears for those who called him, for you’ll know he chose to go.”

Lagniappe

I took this photo of the Twin Towers in September 1980. This was my first visit to the World Trade Center—a mere seven years after the towers opened and almost 21 years to the day before they were toppled.

Thank you for introducing me to Laurelyn, the great-great grandfather whose surname I carry would be sad to hear how little Irish culture I know.

-----------------

Robert - One thing I can add, please forgive if this I am repeating myself, although perhaps that is an old man's privilege.

Why should a person get to know a Gold Star family?

Because it’s one thing to talk about the sacrifice our veteran’s made for our freedoms.

It’s an entirely different thing to meet and befriend a family who has lived with the loss every day of their lives.

You can never fully understand the loss and the grief - but at least you can get a glimpse of what it cost them.

You are so correct. A few years back, I noticed that the name of Purdue physics doctoral student Harry Daghlian, who died of acute radiation poisoning from an accident at the Manhattan project when the so-called "Demon Core accidentally went supercritical during neutron reflection experiments, was missing from a plaque listing faculty, students, and alumni who gave their lives in the Second World War. I wrote university President Mitch Daniels pointing out the omission and asking for his name to be added, as he was an employee of the War Department Army Manhattan Engineering district working on a critical project that played a crucial strategic role in winning the Pacific War.

I was disappointed when Daniels refused to add his name to the plaque because he was not a uniformed soldier, but at least he offered to put a separate one up beside it in the Purdue Memorial Union to honor Daghlian. To me, it was an insult to his memory to say that because he was a civilian employee of the Army rather than a commissioned officer, his sacrifice in the war effort was somehow less meaningful. That is such a radically different attitude than existed during the Second World War itself, when NOAA meteorologists on Coast Guard weather ships were awarded military decorations, and the first Purple Hearts awarded went to Honolulu civilian firefighters who died in the Pearl Harbor attacks.

I grew up an Air Force brat - my father left for the third of his four Vietnam tours on the day I turned one month old. I was an Air Force ROTC cadet in college until I was washed out due to asthma during my commissioning physical. I went on, like you, to graduate work in health economics and policy, and found a way to apply it to the problems that arose from al-Queda. That doesn't mean I didn't serve my country and contribute to efforts in the War on Terrorism - I was a member of two CDC antiterrorism boards, involved in public health preparedness and chemical/biological civil defense planning in two states, and consulted with Joint Forces Command/JIWC on medical civil affairs doctrine in light of the then-new Counterinsurgency manual. I played a role in DoD exercises on how to deal with post-surge Iraq and organizing stability operation efforts, working with people like Dave Kilcullen and Isreali General Benny Ganz.

Not all contributions come from being shot at - those made on the home front can be just as critical if not more so than those on the front lines. I believe it is a shame that the efforts of Lt. General Lucius Clay in coordinating war production and strategic logistics in the Second World War are nearly forgotten while a bumbling poseur like Douglas MacArthur was awarded a Medal of Honor. Montgomery Meigs and Herman Haupt made as critical of contributions to the Civil War as a Sheridan or Hancock, but do not get the recognition - and without the efforts of civilian financier Jay Cooke, the US could not have funded that war effort.