Pundit Asks If "Trump Is Actually Warren Harding"

Pundit needs to know that Harding was bold and enlightened on civil rights & civil liberties and ushered in peace, prosperity, bipartisanship, cautious internationalism, and innovative management

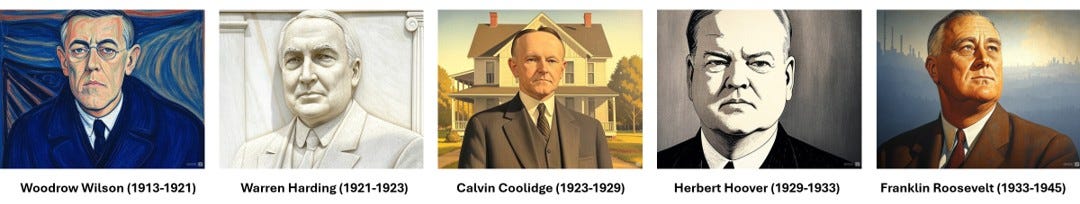

Over at the Persuasion substack, Sam Kahn looks at Donald Trump’s stands on economics, immigration, and foreign policy and asks whether “Trump Is Actually Warren Harding” (or Calvin Coolidge or Herbert Hoover). He asserts that Trump “is reversing the New Deal and sending us back to … the 1920s.”

Whether Trump’s end goal is a pre-New Deal, Harding-esque presidency is a worthy topic for discussion. (Last week, his “Ensuring Accountability for All Agencies” executive order seemed to reclaim powers that FDR delegated to independent agencies.) But in comparing Trump to Harding, Kahn steps into a trap (for reasons not unique to him) and squanders the possibilities of the question. He doesn’t compare Trump to Harding, Coolidge, or Hoover, but rather to cartoonish depictions of those three, long promulgated by ideologically fervent, economically ignorant historians. Below, I’ll quote Kahn and explain my objections.

Importantly, this essay is about the 1920s and 1930s, not the 2020s. In this essay, you’ll find no opinions on Trump or his policies.

THOSE WHO WRITE HISTORY

Kahn himself recognizes and describes the historiological trap that scholars have set—and then he sticks his foot straight into its jaws.

KAHN: “What’s interesting in thinking about the politics of this period is how entirely it has been framed by what came after—history is written by the winners, and the Republicans of this era weren’t, ultimately, the winners.”

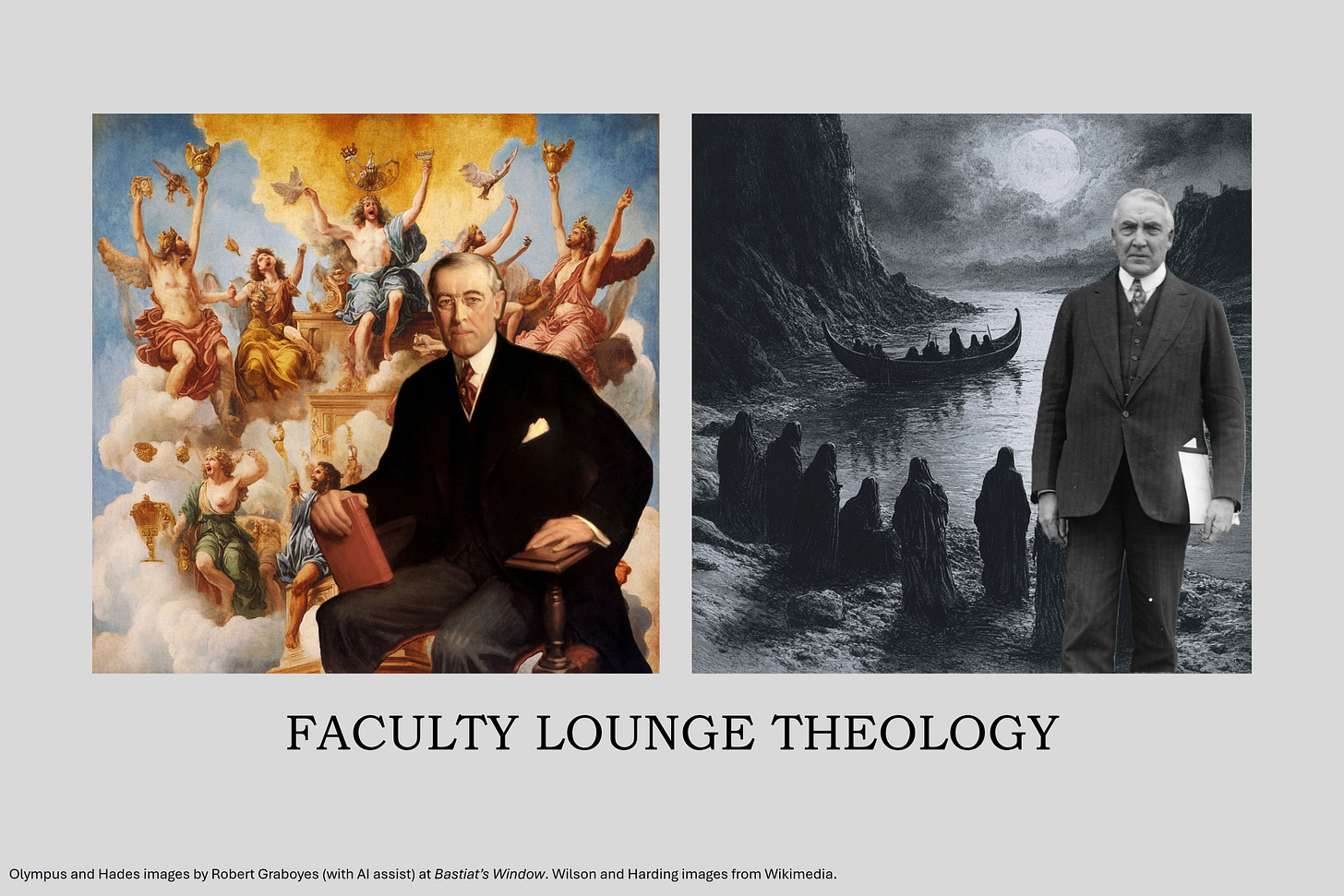

Bingo. Post-New Deal historians painted Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt as saints and Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover as demons—all based on economically malformed narratives.

KAHN: “[T]he gist of Trump’s actions, his odd historical obsessions—the more convinced I am that I’m looking at the policies of the Harding/Coolidge/Hoover interregnum (a period of history that’s been largely mothballed and its three presidents deemed failures).”

Bingo, again. They’ve been judged failures and mothballed—but the judges and mothballers have long been left-leaning partisan ideologues. They created a false perception that Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover were nearly identical in terms of policy and that FDR was a radical departure from all three—a progressive visionary along with a highly vaunted Woodrow Wilson. In fact, Harding’s and Coolidge’s styles of governance were similarly constrained, whereas Hoover was an aggressive interventionist who effectively launched the New Deal before FDR in all but name. As Hoover himself said in 1932:

“We might have done nothing. That would have been utter ruin. Instead, we met the situation with proposals to private business and to the Congress of the most gigantic program of economic defense and counterattack ever evolved in the history of the Republic. We put that program in action.”

One can argue (as I do) that the Great Depression was long and deep because Hoover’s and Roosevelt’s endless meddling made it impossible for businesses to plan and rebuild. Every time they tried, Hoover or Roosevelt changed the rules. And, looking backward, Wilson had been a malevolent force whose fingerprints were on many of the 20th century’s disasters.

To properly understand the positives and negatives of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover, it’s essential to understand just how badly FDR’s presidency flailed prior to his astonishing success as a wartime leader. Contrary to the popular perception that the New Deal ended the Depression, FDR’s own Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., described the New Deal’s failure in 1939:

MORGENTHAU: “We have tried spending money. We are spending more than we have ever spent before and it does not work. … We have never made good on our promises. ... I say after eight years of this Administration we have just as much unemployment as when we started. ... And an enormous debt to boot!”

Especially intriguing is that Morgenthau’s statement seems to consider 1931 (midway through Hoover’s term) as the start of the New Deal, rather than 1933, when Roosevelt assumed office.

For most of his first two terms, Roosevelt was little or no more internationalist than his predecessors. As I wrote recently:

GRABOYES: “Had FDR left after two terms, his legacy would be eight years of Hooverian economics, Trumpian rhetoric, Machiavellian vendettas, and Chamberlainian nonchalance toward Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.”

[FWIW: In my own five-tier subjective rankings, FDR is in Tier 1—one of history’s greatest presidents (because of his war management). Harding and Coolidge are in Tier 2, along with Madison, McKinley, Eisenhower, and others. Hoover and Wilson are in Tier 5—history’s worst. (I’ve slightly revised my rankings.)]

FROM MOUNT McKINLEY TO MOUNT RUSHMORE

To properly understand Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover—and the abject failure of presidential historians—it is also vital to understand the monster whom these three followed: Woodrow Wilson.

KAHN: “Trump has gotten awfully interested in William McKinley. McKinley is the ‘tariff king,’ McKinley booted the Athabascan traditional name off the tall mountain in Alaska.”

Alaska gold miners nicknamed Denali “Mount McKinley” in 1896 to snub silver advocate William Jennings Bryan. But it was Woodrow Wilson who officially changed the name—in 1917, 16 years after McKinley’s assassination. (BTW, McKinley seemed to be retreating from tariffs by the time of his death.)

KAHN: “At any moment, some presidential historian might pop out of the woodwork to announce that Harding was one of the very worst presidents while his predecessor Woodrow Wilson is somewhere in the foothills of Mount Rushmore. But, actually, that’s not how it was seen at the time.”

Nor should it be seen that way in our time. Rankings by presidential historians have long been an utter and absolute travesty, as I recently described in detail. Post-New Deal presidential historians’ lionization of Wilson and demonization of Harding is sufficient reason to discount anything else they say. In “Woodrow the Terrible, Warren the Good,” I offered the following contrasts between the 28th and 29th presidents:

Wilson was the most racist president in U.S. history—the president who single-handedly resegregated the Civil Service. Harding, in contrast, gave the single most courageous civil rights speech in presidential history.

Wilson opposed anti-lynching laws. Harding endorsed such laws in his campaign.

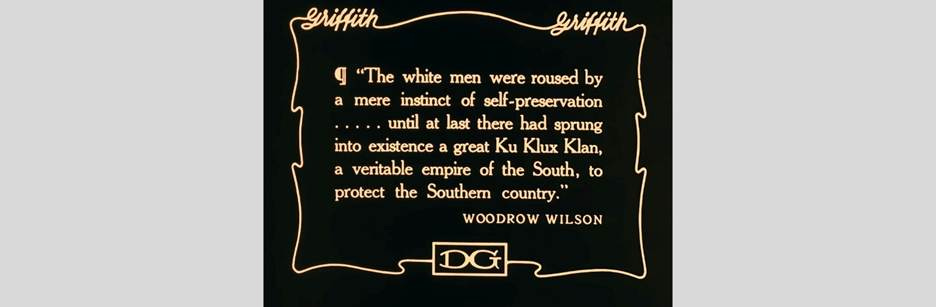

Wilson played a powerful role in reviving the Ku Klux Klan—especially his much-publicized White House screening of the technologically pathbreaking and philosophically repugnant The Birth of a Nation. Accused of having an African American ancestor, Harding’s response was essentially, “Maybe so. Who cares?”

Wilson left office with the economy in free fall. Harding clearly and immediately announced that he would not seek to micromanage the economy; the economy quickly burst back and embarked on an eight-year boom.

Wilson jailed peaceful antiwar protesters. Harding commuted their sentences.

Wilson launched red-scare raids. Harding freed the Socialist leader from imprisonment by Wilson and invited him to the White House.

Wilson’s vengeance and intransigence at Versailles laid the groundwork for Hitler’s rise.

Harding effectively founded the Office of Management and Budget, Government Accountability Office, International Trade Commission, and U.S. Trade Representative. Other than the Secretary of the Interior and Attorney General who tarnished his reputation, Harding’s Cabinet and Supreme Court appointments were outstanding.

Harding was a modest gentleman who worried that he was in over his head. Wilson was an egomaniac who thundered that his election was ordained by God.

AMERICA FIRST

KAHN: “‘America First’ is a clear return to the prevailing isolationist sentiment between the world wars.”

“America First” originated, not with the Republicans, but rather as a campaign slogan for Woodrow Wilson in his 1916 campaign. His central promise was non-intervention—keeping America out of World War I.

KAHN: “[T]he Harding administration, in 1921, introduced immigration quotas which were followed by sweeping restrictions in 1924 that included a wholesale ban on Asian immigrants.”

These were profoundly unfortunate laws, but it’s unfair to blame the 1921 Act on Harding. The cake was baked before he ever arrived at the White House. Clamor for immigration restrictions rolled along like a freight train in 1919 and 1920—thanks to the trauma and aftermath of World War I and to the rising tide of eugenic quackery, which was broadly popular, but especially among progressives. Congress had tried and failed to pass immigration restrictions under Wilson, and the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 just happened to be the one that finally achieved consensus. It had virtually unanimous endorsement by both houses of Congress—Democrats and Republicans. The only senator who voted against it did so because it wasn’t racist enough. The bill was introduced and passed just weeks into Harding’s term.

KAHN: “In 1922, the Harding administration raised tariffs attempting to protect farmers, part of a sequence of tariffs culminating in the massive restrictions of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.”

Terrible ideas, indeed—and born of the same philosophy as Wilson’s agricultural price supports. Wilson’s supports are with us still and, among other things, have contributed mightily to the obesity crisis. (For decades, they have artificially reduced the price of corn sweeteners and artificially raised the price of fresh vegetables.) Smoot-Hawley deserves to be reviled, but it was not the primary cause of the Depression. That honor goes to Hoover’s erratic policies and to catastrophic, ass-backward actions by the Federal Reserve (another Wilson innovation).

KAHN: “[The Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover] administrations pursued proudly isolationist policies, rejecting the League of Nations, avoiding foreign alliances.”

Woodrow Wilson’s intransigence and refusal to make any compromises with the Senate doomed the League of Nations. In contrast, Harding worked amicably with the Senate, involving them deeply in his foreign policy. Seeking to prevent a worldwide arms race, Harding hosted the multinational Washington Naval Treaty and secured unanimous consent from the Senate. (The treaty had tragic effects later on, but that’s another story.)

KAHN: “[A]s one of Hoover’s biographers put it, [Hoover saw] “no conspicuous need to pay attention to the rest of the world.”

This particular biographer was a distinguished scholar, but he was a longtime Democratic political activist, and bias shows in his work. Hoover had a deep, longstanding interest in foreign policy before, during, and after his presidency.

KAHN: “Recently, I was doing some random research into this period and came across a couple of factoids that, insofar as my world is 1920s U.S. domestic politics, rocked my world. One factoid was that Harding was actually a very popular president and was deeply mourned on his death. The other factoid was that the United States’ entry into World War I was, from the perspective of the ‘20s, deeply unpopular and viewed as a mistake (by 1938, a full 70% of Americans would be retroactively anti-war).”

Unless one is confined within the bubble where tenured ideologues preside, it should come as no surprise that Harding was one of history’s most popular presidents and WWI was one of history’s least popular wars. On the latter, Wilson’s re-election campaign was premised on staying out of WWI. Unlike WWII, which clearly pitted evil against good, WWI was arguably a family squabble among Queen Victoria’s grandchildren—Britain’s George V, Germany’s Wilhelm II, Russia’s Nicholas II (whose wife was Victoria’s granddaughter), and others. Yes, Willy was marginally worse than Georgie, and Nicky was a problem child, but Americans had good reason to stay out. (I’m ambivalent as to what we should have done.) Wilson used the war to launch a wholesale assault on civil liberties, bash constitutional norms, and plant geopolitical time bombs that led to Hitler’s rise and WWII.

MORE MYTH-BREAKING

KAHN: “[I] t was very possible to look at Wilsonian and progressive policies and see in them a stark deviation from the founding principles of the republic.”

Wilson’s policies were, in fact, a stark deviation from the founding principles of the republic. Wilson would happily have told you that. He was a longtime political scientist (PhD and president of the American Political Science Association) who despised the Constitution and viewed it as an anachronism that impeded his feverish ambitions. In particular, he viewed the separation of powers and checks and balances as obsolete impediments to presidential power.

KAHN: “It was the era of Babbitt, of a kind of boosterish cynicism in politics—what mattered was business and wealth.”

Babbitt was a fine novel, but it’s fiction, and Sinclair Lewis was (at that time) a Socialist with an axe to grind. It’s a leftist’s condescending caricature of America—not a reliable description of 1920s society.

KAHN: “In the Roosevelt history that I grew up with—a reflection of the consensus that emerged by the World War II era—tariffs had been a terrible blunder, effectively shutting down trade at the peak of the Great Depression and making its impacts incalculably worse. Isolationism was the dirtiest word of all; it was the U.S. equivalent of “appeasement.” From a hard-headed, militaristic standpoint it meant allowing enemies like Hitler and Imperial Japan to get a jump on us; from a humanitarian point of view, it meant turning our back on the rest of the world and allowing the mechanisms of, for instance, the Holocaust to be set into motion.”

Harding was quite involved in world affairs. For example, seeing the shaky status of European Jews, he did much to lay the groundwork for the establishment of the State of Israel. In early 1922, Harding met with the World Zionist Congress leadership for a briefing on the persecution of European Jews. Months later, he signed the Lodge-Fish Resolution calling for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. (In fairness, Wilson was also a Zionist.)

KAHN: “The tough borders policy, and rollback on immigration, came to seem almost criminal with refugee ships turned away at American ports and the refugees returned to Europe just in time for World War II.”

Kahn quite properly links to the “Voyage of the Damned,” in which a callous American president sent nearly 1,000 desperate Jews back to Nazi Germany after reaching Florida. But the incident he decries occurred in 1939, and the president in question was the still-isolationist and somewhat-antisemitic FDR—not Harding, Coolidge, or Hoover. Note that in 1944, the U.S. Treasury issued a document titled: “Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of This Government in the Murder of the Jews.”

KAHN: “[T]he Harding administration had been suffused with scandal (the worst scandals reached public notice only after his death).”

Harding basically had two corrupt cabinet members. His Secretary of the Interior was tried and convicted. His Attorney General was ousted by Coolidge but never convicted. The real scandal that destroyed Harding’s reputation was that he got a 22-year-old pregnant shortly before becoming president and continued the relationship in the White House. When the news spread a few years after his death, the faux-moralizing press and many of his faux-puritanical friends fell to their fainting couches and destroyed his reputation—an early manifestation of cancel culture.

KAHN: "I believe that the clearest precedent is the early ‘20s—there’s a certain rhyme incidentally between the last year of Woodrow Wilson’s administration, with Edith Galt [Wilson] acting as the mouthpiece if not grey cardinal for the bedridden Wilson, and the elaborate courtier kabuki surrounding the mentally declining Joe Biden—and with a pugnacious conservative ideology sweeping into power, focused on isolation, border control, and the removal of governmental interference in the economy.”

The parallel between Wilson’s stroke and Biden’s dementia (and their wives’ machinations) is an absolutely valid topic for discussion. But “pugnacious conservative ideology?” Wilson was miles beyond pugnacious—a sadistic brute in many realms. Harding was (to his own detriment) a bighearted softie. (He said his father told him, “Warren, if you were a woman, you’d be pregnant all the time.”)

KAHN: “The New Deal—by its very name—is usually interpreted as having wiped out the philosophy of the Harding/Coolidge/Hoover administrations and consigning it to the ideological trash heap.”

The operative part of this statement is “usually interpreted as.” This is the usual interpretation of devout New Dealers and their progeny. But it is wrong and nonsensical. It makes no sense to speak of “the philosophy of the Harding/Coolidge/Hoover administrations.” Harding and Coolidge were relatively close philosophically, but Hoover was a proto-FDR whose policies were starkly different from his two predecessors. Harding and Coolidge were not cold-hearted with respect to economic downturns—they simply did not believe that the federal government had the capacity to tame business cycles and feared that meddling could do great damage. Hoover, in contrast was an engineer who thought the economy was as manipulable as a piece of mining equipment. FDR simply took Hoover’s activist policies, ramped them up, and applied American history’s most successful brand name—the New Deal.

POSTSCRIPT

Asking whether Donald Trump wants to return the American government to pre-New Deal norms is a great question. Only time will tell whether he is, in fact, a Harding-Coolidge-style proponent of limited government and cautious internationalism. But any analyst who relies on presidential historians’ stilted, high-blown gibberish will arrive only at misleading answers. Mr. Kahn asks whether Biden-versus-Trump and Wilson-versus-Harding are parallel stories. I’ll close with two quotes to ponder while contemplating that question:

First is a title card from D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), featuring a quote from Woodrow Wilson’s History of the American People (1902):

D.W. Griffith actually toned down Wilson’s words:

“The white men of the South were aroused by the mere instinct of self-preservation to rid themselves, by fair means or foul, of the intolerable burden of governments sustained by the votes of ignorant negroes and conducted in the interest of adventurers. … until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.”

Second is a quotation from Warren Harding’s acceptance speech at the 1920 Republican convention:

"No majority shall abridge the rights of a minority [...] I believe the Federal Government should stamp out lynching and remove that stain from the fair name of America. […] I believe the Black citizens of America should be guaranteed the enjoyment of all their rights, that they have earned their full measure of citizenship bestowed, that their sacrifices in blood on the battlefields of the republic have entitled them to all of freedom and opportunity, all of sympathy and aid that the American spirit of fairness and justice demands.”

I would argue in the strongest terms that Mr. Kahn’s assertion—“Trump is actually Warren Harding”—is not the slam-dunk put-down that his article suggests.

as a side note, Ben Hecht , who was a foreign correspondent for a Chicago paper, says that when he returned to the US in the mid 20s from Germany, sorry for this run on sentence, He had a meeting with Coolidge. A. he was very surprised to find that Coolidge was following what was going on closely. B. He wanted to know what Hecht thought since he had been there for a number of years. So much for one of our underated Presidents.

Fascinating read. Much enjoyed. From a historical perspective, we live in the most interesting of times. If we throw off the New Deal (whether the creation of Hoover or FDR is irrelevant) the US economy may be poised for an astounding run.