Why Impossible Things Are Everywhere

A dozen brief musings on the role of mathematics and God in the ubiquity of highly improbable occurrences.

In the 1983 film, Local Hero, MacIntyre, a young American oil executive, asks Ben Knox, an elderly eccentric living on a Scottish beach, to name the most amazing thing he has ever found washed up on the shore. “Impossible to say,” Ben responds. “See, there’s something amazing every two or three weeks. I’ll let you know the next time.” In Through the Looking Glass, the White Queen tells Alice, “Why, sometimes I've believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

Writing to Max Born in 1926, Albert Einstein wrote of the tension between statistics and God as explanations for the physical universe:

“The theory produces a good deal but hardly brings us closer to the secret of the Old One. I am at all events convinced that He does not play dice.”

In a few days, BASTIAT’S WINDOW will tell of a Canadian man (just for today, I’ll call him “F.B.”), who grew fascinated by a highly specific variety of coincidental occurrence and has spent years traveling the Earth finding examples to document and photograph. Sometimes, his photos and stories are breathtaking and awe-inspiring. Other times, they’re haunting and terrifying. Today’s post is pre-reading for F.B.’s story—an introduction to the omnipresence of things that cannot possibly be. Most of the material below, all on the subject of coincidences, comes from three BASTIAT’S WINDOW posts from 2022 and 2023, when this publication had few readers.

Today’s post is longer than average, but composed of a dozen fleeting little tales. Read all or read just a few. Read them at once, or read them over time.

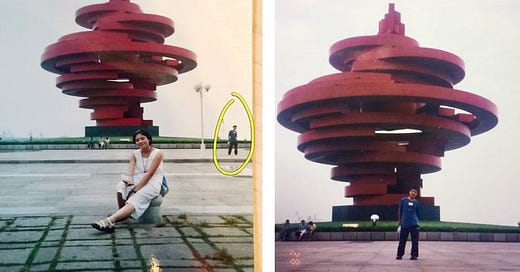

[1] KISMET IN CHINA

In 2022, a remarkable pair of photos, shown at the top of this page, circulated of a couple in China. One had the wife, Xue, posing in front of a monument in Qingdao, with her husband, Ye, seeming to photo-bomb her, posed in a distinctive stance. The other showed Ye at the same moment in a closer-up shot. In both photos, three other tourists were seated in the distance, conversing. The side-by-side photos went viral on social media because they were taken over ten years before Xue and Ye met. Ye happened to thumb through Xue’s photo album—stunned to see himself in her pic. He happened to have a photo of himself snapped at the same moment.

Across the web, people asked, “What are the odds that in a country of one billion people, the guy standing behind you just happens to be your years-in-the-future spouse?” A statistician/friend said, “You can turn [this pair of photos] around and see it as, ‘[I]n a nation with over a billion people, this is bound to have happened with someone.’” The only odd thing is that the couple happened to discover the long-ago coincidence.

[2] THAT SAME TELEMARKETER

Here’s a case I used to present to my stats students. Suppose you’re a telemarketer with a list of 100,000 names. You call a random name from the list and warn them that their car warranty is about to expire. Then you pick a second name from the same 100,000 names and call that person. Keep at it till you have made 150 calls. What are the chances that you will have called at least one person at least twice?

The odds must be infinitesimal, students thought. In fact, there’s a 10% chance you’ve already hit someone twice. Make 370 calls, and the odds are over 50%. In one class, a student shouted, “Ohmigod! The same telemarketer called me twice, and I thought the odds of that must have been astronomical.” (She recognized the caller’s distinctive voice, and he remembered their earlier conversation, too.) Such coincidences happen all the time, I said. The only rarity here was that you noticed it. (See the “Birthday Problem.”)

[3] FRIEND IN TEXAS

Someone told me of his friend, a Texan who sat on a plane next to a gabby fellow passenger. “You’re from Texas! Why, I have a friend in Texas. I wonder if you know him.” The Texan started rolling his eyes, given that his state has nearly thirty million people spread across 268,596 square miles. The gabby passenger named his friend, and it turned out to be the Texan’s next-door neighbor.

[4] THAT NAME CAN’T BE REAL

A friend of a friend had a first name/last name combination that sounded horribly obscene. When he arrived at college, he instantly started going by a different first name to avoid the embarrassment. Decades later, a friend of mine discussed this story (loudly, it seems) while dining out with a large group of people. One of his fellow diners said, “That’s impossible. No one would give their kid that name.” A fellow seated at the next table got up, walked over, said, “Oh, yes they would,” and flashed his driver’s license.

[5] THOMAS JEFFERSON LIVES

In one of history’s most compelling coincidences, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Adams’s last words were “Thomas Jefferson still survives.” In fact, Jefferson had died several hours earlier. It’s a highly unlikely event, no doubt, but it would be even more unlikely if the world had no such highly unlikely events.

[6] DEGREES OF SEPARATION

A friend emailed me a lovely video of a Swiss alpenhornist giving a concert performance. He explained, “Soloist is a friend of a friend. Not unusual to be two degrees separated from just about anyone in the music world. Hell, she’s probably a friend of a friend of yours too.” I looked her up on Facebook. We had no mutual Facebook friends, but two of her friends shared the same mutual friend with me. So, this musician is not a friend of a friend to me (at least not on Facebook), but she is a friend of several friends of a friend. In the past I’ve come across faraway total strangers on Facebook who share multiple mutual friends with me—often from very different parts of my life. For some reason, one of my childhood accomplices shows up on lots of these coincidental connections—making him the Kevin Bacon of my circles. I’ve even had strangers message me, asking how I know this guy.

The internet just makes coincidences easier to find. With facial recognition software crawling all over social media (TikTok!), I suspect that over time, miraculous discoveries like that of Xue and Ye will become commonplace and lose a bit of their magic. (Kind of a shame, really.)

[7] HAND OF FATE

Statistician David J. Hand’s book, The Improbability Principle: Why Coincidences Miracles, and Rare Events Happen Every Day opens with a story about actor Anthony Hopkins. In summer, 1972, Hopkins was signed to play a leading role in a film based on George Feifer’s novel The Girl from Petrovka, so he traveled to London to buy a copy of the book. Unfortunately, none of the main London bookstores had a copy. Then, on his way home, waiting for an underground train at Leicester Square tube station, he saw a discarded book lying on the seat next to him. It was a copy of The Girl from Petrovka.

As if that were not coincidence enough, more followed. Later, when he had a chance to meet the author, Hopkins told him about this strange occurrence. Feifer said that in November 1971 he had lent a friend a copy of the book—a uniquely annotated copy in which he had made notes on turning the British English into American English (“labour” to “labor,” and so on) for the publication of an American version—but his friend had lost the copy in Bayswater, London. A quick check of the annotations in the copy Hopkins had found showed that it was the very same copy that Feifer’s friend had mislaid.

As a stats professor, I understand why wildly improbable occurrences are so common—but that doesn’t make them any less enjoyable. As Professor Hand wrote, “[A] grasp of the cause of the colors of the rainbow doesn’t detract from its wonder.” He explores the connections between superstitions, prophecy, miracles, and strange occurrences of all sorts. His book is scattered about with a couple who survived separate train crashes, holes-in-one, methodologies of suicide, ESP, butterflies, the universe, thoughts on human cognition, the search for four-leaf clovers, people who win the lottery twice, and people who are struck multiple times by lightning. Hand even provides advice on how to make practical use of all of this knowledge.

[8] BULGARIAN LOTTERY

I was reading Professor Hand’s book and began a section on wild coincidences that show up in lotteries. Before I got too far into that section, I closed my Kindle so my wife and I could watch a pleasant little British TV series called The Outlaws, about an oddball group of seven people in Bristol doing community service (“community payback” in Britain) after committing petty crimes. One character is an aspiring Oxford scholarship student arrested for shoplifting.

In one scene, a policewoman asks the would-be Oxonian why she was spotted near the scene of a wee-hours drug robbery involving one of the other members of her community-payback crew. She says, “I don't know - a coincidence?” (Which it wasn’t.) The police detective said, “Quite a big coincidence, wouldn't you say?” The young woman then says, “Statistically, coincidences are more common than you think. … In 2009, the Bulgarian lottery announced the same six winning numbers on two consecutive draws. People thought was a fix, the government investigated, but no tampering was found. It was just a coincidence. … Just Google ‘Bulgarian lottery.’”

My wife looked at me and said, “That sounds like it could be in the book you’re reading.” The next morning, I opened the book, and right away, I was reading Professor Hand’s description of the 2009 Bulgarian lottery. The numbers 4, 15, 23, 24, 35, and 42 came up on September 6, 2009, and then did so again four days later. Dr. Hand also described this case in Scientific American.

[9] BULGERIAN LOTTERY

In 1991, another remarkable-lottery-coincidence made the headlines in Boston. Whitey Bulger, a notorious gangster (and FBI informant) whose brother was a high-ranking politician, won the state lottery at an unusually propitious moment. The authorities were closing in on his illegal operations and he desperately needed a legitimate stream of income. Suddenly, Bulger and three associates came into possession of a winning ticket, purchased from a store owned by Bulger. The four men shared a prize of around $14,000,000.

A great public debate ensued over whether this was a coincidence or something nefarious. (It was likely something of a combination of the two.) Most likely, one of his associates had won the ticket, and Bulger strong-armed him into sharing the earnings as a means of money-laundering. Bulger had a lot of associates, so the possibility that one would win the lottery someday was a lot greater than just the possibility that Bulger would win. Assuming that Bulger did, in fact, force the actual winner to share his ticket further reduces the improbability of a famous thug lucking out in this manner.

Bulger’s apparent winnings launched a thousand debates on questions moral, philosophical, jurisprudential, and even theological. The story became even more complex when Bulger went into hiding for 16 years, raising questions about whether he could receive his portion of the payout via proxy. The website Crimereads.com has a nice writeup on the story. At the very least, there was some karma in that Bulger’s winnings were instrumental into bringing down some of his associates. Bulger was eventually murdered in the most horrific manner in prison, so “lottery-winner” isn’t the first term that comes to mind when his name is mentioned.

[10] BOLGERIAN LOTTERY

Ray Bolger played the scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz (1939). This story has nothing to do with Bolger or lotteries, but it does involve Bolger’s most celebrated film—and I couldn’t resist adding “Bolgerian” to the “Bulgarian” and “Bulgerian” sequence.

Actor Frank Morgan played the Wizard of Oz in the eponymous 1939 film. He also played a number of other characters, including Professor Marvel, a traveling soothsayer on the plains of Kansas. According to a story told by various members of the production crew, they wanted Professor Marvel decked out in attire that was once grand, but now worn-out. He ended up with a frayed great coat purchased from a Hollywood second-hand store.

One day, the story goes, Morgan turned one of the coat pockets inside-out and discovered a label bearing the name “L. Frank Baum.” Baum, the author of the Oz books, had died 20 years earlier. Assuming the story is accurate, the film crew received written, notarized confirmation of authenticity from Baum’s tailor and later presented the coat to Baum’s widow. Some accused the film crew of staging a publicity stunt with a fake story, but the crew insisted that the whole thing was a great coincidence. Fact-checking site Snopes.com investigated and rated the story as an unconfirmable legend.

[11] HAND OF GOD

After reading my 2022 essay on coincidences, a colleague in New England wrote to note one more coincidence. Two days before my piece appeared, Deborah Netburn, who writes on “faith, spirituality and joy” for the Los Angeles Times, had written an article on similar territory: “Strange coincidences: Are they fluke events or acts of God?” Netburn did a nice job in presenting alternative viewpoints on the nature of coincidences. She cites Professor Hand as representing the rationalist end, of interpreting coincidences; Hand, she says, finds that “most coincidences are fairly easy to explain, and he specializes in demystifying even the strangest ones.”

She also explores more spiritual interpretations of the nature of coincidence. Her archetype for that view is Dr. Bernard Beitman, who, in 1973, had an inexplicable choking incident (when he wasn’t eating or drinking), only to learn that somewhere around that time, his father, 3,000 miles away, was choking to death on his own blood. As Netburn writes:

“Overcome with awe and emotion, Beitman became fascinated with what he calls meaningful coincidences. After becoming a professor of psychiatry at the University of Missouri-Columbia, he published several papers and two books on the subject and started a nonprofit, the Coincidence Project, to encourage people to share their coincidence stories.”

By the way (coincidentally?) the colleague who sent me Netburn’s article had written long ago about Whitey Bulger.

[12] SUN AND MOON

If Beitman represents the spiritualist end on coincidences and Hand represents the rationalist end, I generally fall considerably closer to Hand’s rationalist, mathematical terrain. But witnessing what is perhaps the greatest coincidence across human history gave me one of the two most spiritual moments of my life. One of those moments, in 1986, was witnessing the birth of my son. The other, on March 7, 1970, was witnessing a total eclipse of the sun. As I wrote in 2017 and again in 2024 (“Sun, Son, Kronos, Kairos”):

“At 99 percent total, the eclipse was pretty interesting. A bluish veil descended over earth, birds made night sounds and the few passing cars had their lights on. But the moment the eclipse reached 100 percent totality was incomparably different from the view a split second earlier — surreal beyond imagination. … Shadow bands — wavy lines like ripples on a pond — stretched for miles across the landscape. The corona surrounding the blackened moon was a ring of pure white brilliance resembling burning magnesium. Only one other time — the birth of my son — have I witnessed anything so miraculous and remote from my life’s other experiences.”

In “A Total Solar Eclipse Feels Really, Really Weird,” astronomy writer Bob Berman does justice to the event in a way I’ve never seen from any other writer.

“Have you ever witnessed a total solar eclipse? Usually when I give a lecture, only a couple of people in an audience of several hundred people raise their hands when I ask that question. A few others respond tentatively, saying, ‘I think I saw one.’ That’s like a woman saying, ‘I think I once gave birth.’”

In a passage that gives me great thanks to have lived during this period of earth’s history, Berman described the, yes, astronomical unlikelihood of solar eclipses.

“No discussion of totality should omit the strange science lurking behind it. It starts with a bizarre coincidence: the moon is four hundred times smaller than the sun, but it also floats four hundred times nearer to us. This makes the two disks in our sky appear to be the same size. Now, if the moon appeared larger than the sun, it could still occasionally stand in front of it, but it would also blot out the dramatic prominences along the sun’s edge, those geysers of pink nuclear flame. So for maximum amazingness, these bodies must have identical angular diameters—i.e., they must appear to be the same size. And they do.

The moon wasn’t always where it is now, which makes the coincidence even more special. The moon has really just arrived at the ‘sweet spot.’ It’s been departing from us ever since its creation four billion years ago, after we were whacked by a Mars-size body that sent white-hot debris arcing into the sky. Spiraling away at the rate of one and a half inches per year, the moon is only now at the correct distance from our planet to make total solar eclipses possible. In just another few hundred million years, total solar eclipses will be over forever.”

When the moon exactly covered the face of the sun on that long-ago morning, my overwhelming thought was, “This can’t possibly be accidental.” For that moment, I was firmly in Dr. Beitman’s spiritualist camp. I have since given numerous lectures in which I explain that coincidence in Dr. Hand’s rationalist terms. But I am content to retain the cognitive dissonance inherent in holding both views.

A few years ago I was interviewing someone for my book on textiles. With some embarrassment she asked whether I might know a journalist neighbor of hers, despite knowing that 1) there are a zillion journalists 2) we lived a continent apart. Although we'd since lost touch, her journalist neighbor had been the matron of honor at my wedding.

> “Have you ever witnessed a total solar eclipse? Usually when I give a lecture, only a couple of people in an audience of several hundred people raise their hands when I ask that question. A few others respond tentatively, saying, ‘I think I saw one.’ That’s like a woman saying, ‘I think I once gave birth.’”

See also: spiritual experiences. For people who have personally felt God's hand in their lives, it is an unmistakable and distinctive thing, which people who have not simply aren't equipped to fully comprehend. Miracles are very real. Anyone who's experienced one *knows* that, and anyone who hasn't does not have the necessary basis by which to claim that they're not.