Concrete Lessons from Abstract Expressionists

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman

Please consider subscribing to Bastiat’s Window—and please share the site and its articles with friends.

FOREWORD, BY BOB GRABOYES: Some of the best-received Bastiat’s Window essays have been those offering advice on childhood, college, and job markets (e.g., Whence Fall Snowflakes, 20 Job Tips for 2020s 20-Somethings, Getting a Job In Spite of Your Education). This one is by my wife, Alanna—the wisest soul I’ve ever known.

Coming from a family of modest means, high-priced universities weren’t in the cards. Alanna attended Queens College (CUNY) for $34 per semester (c.$300 in 2023 dollars). There, she studied art with cutting-edge abstract expressionists whose works hang today in the world’s finest museums. She’s always told how their advice guided not only her art, but also her career as a librarian, technologist, and educator. So, I asked her to write two essays. “SoHo + 45: Avant-Garde's Hot Center Revisited” described how she wrote the first book ever published on New York’s SoHo Arts District. Today’s essay describes the wisdom given by her art professors.

What is striking about these lessons is how opposite they are to what students commonly hear today. Alanna’s professors demanded excellence, introspection, civil discourse, respect for conflicting perspectives, precision, and autonomy—in other words, adulthood.

A half-century on, I offer heartfelt thanks to seven instructors by sharing seven lessons they gave me, plus a bonus lesson from my encounter with Salvador Dalí.

Charles Cajori (1921-2013): To hell with complacency.

Cajori taught me to spurn complacency and continually challenge myself.

A 2014 New England Public Radio eulogy stressed Cajori’s deep connections with the jazz world that was intertwined with abstract expressionism. A 2000 New York Times piece said:

“In painting, Mr. Cajori has tended toward an expansive, colorful expressionism, part Matisse, part de Kooning. His drawings have a grittier feel. They are all black and white, are made in charcoal or pencil, and have a fiercely agitated concentration with much heavy overdrawing and erasing and, often, white paint added.”

Cajori was a showman—funny, intimidating. One time, some pre-med students heard our class had nude models and came to “observe.” He didn’t let them gawk. He gave each a large pad of paper, a pencil, and a seat right in front. He forced them to draw—in a sense, stripping them naked in front of the art students. Deeply intimidated, they drew tiny little nudes on their huge pads.

Cajori was totally honest, and you knew he was brilliant. He told us not to look not at objects, but rather, at the spaces between objects (“interstices”). To see shapes, not things.

One day, he gazed at the painting on my easel and said, “You’re happy with it, aren’t you?” Timidly, I said yes. He told me to dip my brush into some paint and make a huge stroke across the canvas—top to bottom. He looked at me and said, “To hell with it.” He didn’t want me to be happy with it. He thought it was OK, but that I could do better. After “vandalizing” my painting, I saw the problems and began solving them.

Nowadays, I’ll take a painting I think I’ve completed, stare at it for months, and restart the process. Below are four examples: (1) My minimalist painting, “Coronado Beach Soccer,” hung on my wall for years. At some point, somehow, the painting “told me” how I could better capture my feelings about the day I visited Coronado Beach. The lone soccer ball and lonely pylons gave way to 22 umbrellas—some earthbound, some not. The painting became, “A Day at the Beach.” (2) An austere painting of vegetation after a Virginia snowfall became the Flame Nebula, inspired by photos on NASA’s website. (3) A spare New Mexico landscape acquired the Rockies, Rio Grande, and rows of vegetation. (4) A sparse desert became Taos Pueblo, with vegetation below and Georgia O’Keefe clouds above.

These reworkings occurred because Cajori forced me to stand back, reevaluate my work, and solve problems. He taught me not to see things in terms of “good,” “bad,” “like,” and “dislike.” For Cajori, process was as important as end-product. Those words have echoed throughout my life.

Years later, I was an intermediary between the public library system where I worked and the county’s computer department. I had to force 120 computer-phobic people to step outside their comfort zones. Metaphorically, I made them vandalize their canvasses—and say to hell with complacency and trepidation.

John Ferren (1905-1970): Observe calmly, and question yourself.

Ferren was the anti-Cajori—serene, calm, Buddha-like. I had a bit of fear of almost all my teachers, but not Ferren. He was like the Dalai Lama (whom Bob and I saw speak in 2012). Recently, I learned that Ferren was, in fact, interested in Zen Buddhism. In comportment and painting, Ferren also reminded me of Matisse—dignified, formal, sincere, a bit other-worldly.

Ferren is a hero to Bob because he worked with Alfred Hitchcock on Vertigo (1958). He produced the film’s dream sequence (in the video above) and also painted the iconic “Portrait of Carlotta” that haunts Jimmy Stewart’s dreams. Years before, Ferren was an American in Paris, of whom Gertrude Stein said:

“Ferren ought be a man who is interesting, he is the only American painter foreign painters in Paris consider as a painter and whose paintings interest them. He is young yet and might do . . . that thing called abstract painting.”

My own paintings use bright colors and abstract shapes, and much of that derives from Ferren. He also taught us how to interact with others—to listen objectively and avoid argument. I tried conducting myself that way with coworkers and students. As an educator, I taught students the importance of questioning their own beliefs. To the extent I succeeded, I owe a debt to Ferren.

I was deeply fortunate to have studied with him, as he passed away a year or so later. Perhaps he already knew his end was approaching. If so, his serenity was the ultimate life lesson.

Herb Aach (1923-1985): Think large, and don’t hide.

Aach was my most supportive teacher. He was a big, lovable teddy bear of a man—relentless, but not gratuitous, with praise. He offered criticism, but always in a positive, encouraging manner.

Born in Germany in 1923, Aach fled the Nazis in 1938, joined the U.S. Army in 1942, and became a citizen in 1943. He was deeply interested in color theory and had studied under John Ferren two decades before I had. His fascination led him to author a landmark translation of Goethe’s Color Theory. Aach taught me to see color and had me read great masters of color. John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, R.L. Gregory’s Eye and Brain, and Rudolf Arnheim’s Visual Thinking guide me still.

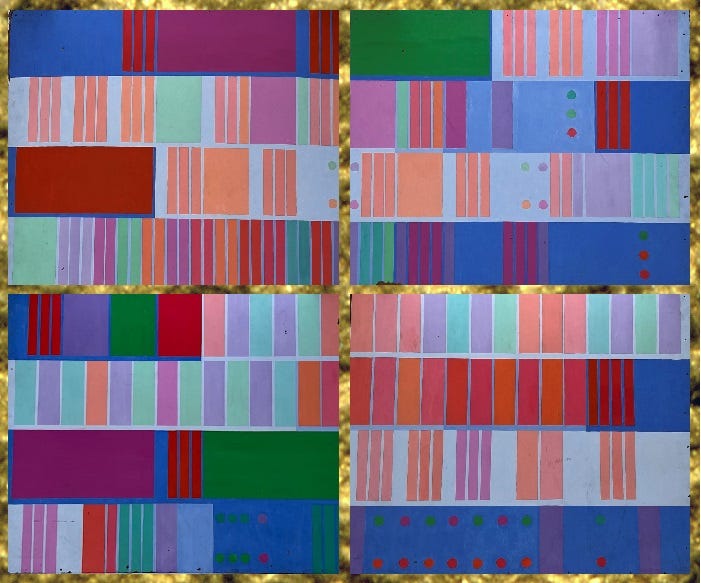

Aach only wanted me to do monster-size paintings. He said with big paintings, you can't hide your mistakes. You can't fix things by making little adjustments. You have to be clear in what you're saying. The biggest, heaviest painting I ever did, on Masonite, visualized the opening passage of Beethoven’s 5th. Shown below, the colors and shapes reflect the notes—da-da-da-daaah, da-da-da-daaah. This was to be part of my senior thesis. Another professor insisted that I not mix art and music, but Aach fiercely defended my right to do so and prevailed.

My small apartment had nowhere to store my Beethoven. Aach took it to his tiny office and leaned it against a wall for months, showing it off to all who visited.

I love doing large paintings more than small ones but don’t paint so many because they’re harder to sell and need lots of storage space. The image above is split into four parts because we once lived in a house that had no space to display or house the painting. We cut it up and kept the pieces. Someday, we’ll reassemble it, but here, we do so graphically, mimicking the Japanese technique of kintsugi (accentuating breakage with gold lacquer).

Late in my career, I oversaw the design and construction of two state-of-the-art libraries—the biggest canvasses I ever worked with. Dealing with architects, contractors, and administrators, I knew from Aach that I had to be clear in what I was saying and that I couldn’t hide mistakes with small fixes.

I’ll always adore Aach and will always be grateful for his support and mentorship, but my relationship with him ended on a more poignant note than with anyone else. After college, I needed to earn a living and couldn’t afford to be a starving artist. I went to work in the Garment District as a textile designer. Aach thought that was beneath me and was upset that I didn’t pursue a career in fine arts. Forty years or so later, circumstances allowed me to focus again on art. Much of my painting these days is on fabric, not canvas, combining what Aach taught me about color with my long-ago work on textiles. I wish I could show dear Professor Aach how he has guided my recent work.

I’ll mention four other professors who influenced me greatly. These sections are short, not because they were less important, but because I’m hitting Substack’s word limits.

James Brooks (1906-1992): Seek unconventional perspectives.

Brooks was a guest instructor, but I immediately gravitated to him. Like Aach, he was fatherly. He was a sort of gentle Cajori. He would never tell me to deface my painting, but he would tell me to turn it upside-down or sideways to see colors, shapes, spaces in different ways. Today, I instinctively view my canvasses and fabrics from different angles. In teaching, I used an analogous technique—Edward de Bono’s Six Thinking Hats—to force students to view ideas from different perspectives.

Robert Pincus-Witten (1935-2018): To know anything, know history.

Pincus-Witten taught us that every painting and every artist has a story—that you can’t understand art without understanding history. He had us critique the masters as we would contemporaries. He shared stories about paintings so we might understand their context—why and how they were created. These insights were valuable outside of art. When I oversaw the design of a school library in the 2010s, architects initially presented me with a design that was fine for the 1950s—but not for today. I had to help them understand why tall shelves, rectangular tables, solitary seating, near-silence, blind spots, and librarian-student separation made sense back then, but not in a world of digital info, headphones, group learning, and illegal drugs. To meet 21st century needs, architects had to understand 20th century realities.

Kes Zapkus: (1938-date): See simplicity before seeking complexity.

Zapkus taught us the formidable power of black, white, and gray—the richness of a monochromatic world. From there, we progressed to shades and tints—the application of black and white pigments to colors. Zapkus taught me to begin a work by seeing skeletal structures, and then progressing to the nuance of the full spectrum and variations on those colors. This became a metaphor for my career in education. Teaching research methods, I told students to look at their topics initially in black-and-white, so they might later grasp that almost nothing is, in fact, black or white.

Harold Bruder (1930-date): Be precise, and be practical.

Bruder was radically different from the other professors. Abstract expressionism was a wild, unconstrained frontier of art, but Bruder was a graphic artist whose paintings were realistic. He worked with trademarks and advertising, similar to the industrial art of Raymond Loewy. Bruder was all about precision, accuracy, sharp edges. Much of my career involved high-tech systems—work that demanded great precision. Bruder’s lessons made that possible. More than any other professor, Bruder understood my need to earn a living, and his understanding gave me license to step away from fine arts and pursue the life I chose. For that, I am eternally grateful.

Lagniappe

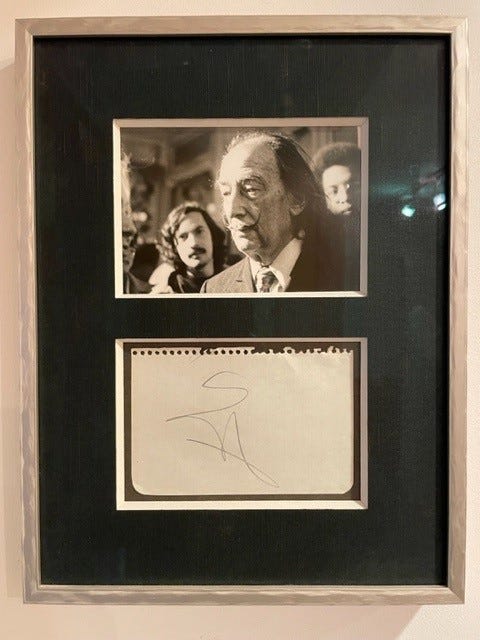

Salvador Dalí (1904-1989): Choose your goal, and get there first.

Dalí isn’t an abstract expressionist, and he wasn’t my professor. But I learned a lesson from him, though it was more about me than about him. My class was invited to hear him speak at the St. Regis Hotel. We thought the event would be intimate, but when we arrived, there were over 100 attendees from schools all over town. We sat on the floor till someone told us that Dalí was in a different room. I knew this was a once-in-a-lifetime experience, I'm 5'0" and didn't want anyone blocking my view. I zoomed through the crowd and sat directly in front of Dalí.

He sat above us on a throne, with his black suit, cape, and cane. Toward the end, I noticed handlers preparing to escort him out. I leaped up with my big, heavy 35mm camera in one hand and notepad in the other. I snapped a picture, held out my pad, and said sternly, “Please autograph this.” Dalí, intimidating as he was, complied. Had I been shy or slow, I wouldn’t have the treasure pictured above.

I'm a philistine, without a speck of artistic talent or taste, but your comment about Cajori and the space between shapes reminds me that for what it's worth I've always thought that what really distinguishes Beethoven from lesser composers is his mastery of silence -- of the space between notes. Each one of those key silences seem wonderfully deliberate, exquisitely hand-carved out of ebony and the midnight sky between stars, and critical to the ear's voluptuous experience. It's the first thing I contemplate when I hear a new recording, particularly of the Fifth: does the conductor hold the orchestra to *exactly* the right time between key notes, especially in the 2nd movement, so that the tension is perfectly right? There is no haste, the silence is fully ripe, but on the other hand you feel if it went on just two more milliseconds a bow would snap, a trumpet explode, an oboist giggle or fart.

Thanks for an interesting essay.

You are rich ! These mentors, willing or not, knowing or not, are lucky that you carry their stories and discoveries melded with your own ...